"THE AUDIENCE WONDERS WHETHER THEY ARE WATCHING A STAGED OR A REAL ARGUMENT"

Conrad Brunstrom, literary scholar and blogger, posted today about Dionysus In '69:

Conrad Brunstrom, literary scholar and blogger, posted today about Dionysus In '69:Many years ago, I read a book by Bill Shepherd about the experience of preparing for and performing Dionysus in 69. Shepherd describes the process of rehearsing for Dionysus as something akin to cult membership – [an] exhausting and all demanding process that lasted many months. This kind of “living theatre” has a tendency to treat the performance as a mere symptom of a process rather than as the defining end product.I recall that Shepherd describes how Richard Schechner created and sustained The Performance Group in that garage that wasn’t really a garage. At one point, he reported to the cast that Jerzy Grotowski (no less) had seen an early production and complained that the partial nudity looked a bit tacky. On Grotowski’s second-hand authority therefore, Schechner persuades the cast to get the rest of their kit off.

The name Dionysus in 69 does a number of things in the context of a 1968 production. 69 is a rude number – which helps. It’s also “next year” – an imminent revolution. And of course, there is the important context of the 1968 US election, in which the Vietnam War is a decisive issue. [Finley]-Dionysos is the candidate to become President in 69.

The casual use of “real” names alongside Euripidean roles has a genuinely unsettling effect in the production. The audience wonders whether they are watching a staged or a real argument, a play or a group therapy session.

Does it all work? Is the blood and the nudity and the dicing with mental health all justified in the name of art? Well…. yeah… I think so. I was worried that the production would seem desperately ponderous and self important. In fact, the wit of the production is what shines through. Euripides is a disturbingly funny playwright, and enough of the Arrowsmith translation is integrated into this theatre work to demonstrate the joyous absurdity of religious conflict. And William [Finley] is a remarkable Dionysos – calm, comical, terrifying and seductive. The scene where he demands oral sex from Pentheus and/or Bill Shepherd is as careful and exquisitely delivered as anything I’ve ever seen on stage or in a film, or in a film that’s also a stage or a stage that’s also a film. Yes, it’s heavy on sex and death and liturgy – but there is a constant playfulness on show here as well. It’s consistently entertaining.

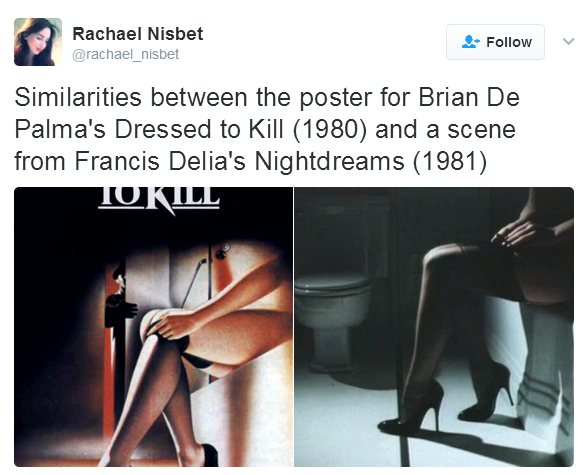

Brian De Palma uses a split screen technique to show the audience and the cast simultaneously. It’s a technique he would use in more famous films like Carrie and Dressed to Kill. On the one hand, this reminds us that everything we see is designed for a live audience. On the other hand, this “division” of the screen is precisely the division that is continually being violated by the Performance Group. It is increasingly impossible to separate cast from audience – and not just when they’re all groping one another. Apparently, this film joins together two separate productions. I for one, cannot see the join.

The one barrier that can’t be transcended of course is the essential “pastness” of film itself. The cast transgress every conceivable barrier between actors and audience, between cast names and “real names” and finally, with the triumphant bursting forth into the streets – between theatrical reality and the so-called “outside world”. The final gimmick that De Palma might have added might be a smashing through a cinema screen to terrify a theatre full of complacent movie goers. And then we’d be able to extrapolate and imagine Dionysos and company bursting out of our smaller screens to invade our dull and safe little worlds.

Miriam Colón, who portrayed Tony Montana's mother in Brian De Palma's Scarface, died Friday. She was 80. According to

Miriam Colón, who portrayed Tony Montana's mother in Brian De Palma's Scarface, died Friday. She was 80. According to

I really enjoyed seeing Jordan Peele's uproarious Get Out in a packed theater a couple of weeks ago, and found it to be one of the more creative films I've seen in a while.

I really enjoyed seeing Jordan Peele's uproarious Get Out in a packed theater a couple of weeks ago, and found it to be one of the more creative films I've seen in a while.  Brian De Palma's Blow Out will be the first of five films to be screened and discussed as part of a five-week course titled "Film/Style." The course, currently filled to capacity, will be taught by Diana Martinez at

Brian De Palma's Blow Out will be the first of five films to be screened and discussed as part of a five-week course titled "Film/Style." The course, currently filled to capacity, will be taught by Diana Martinez at