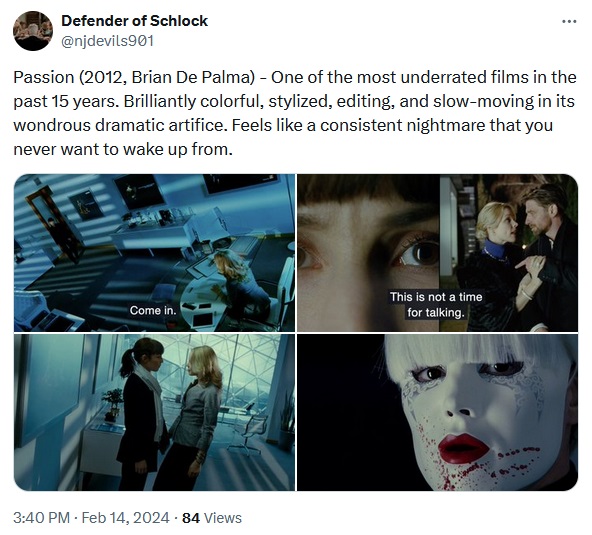

A TWEET FROM VALENTINE'S DAY

Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | September 2024 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

| 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 |

| 29 | 30 | |||||

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

Voyeurism and the methods used in recording voyeurism have long been prominent themes in De Palma’s work. Throughout his five-decade filmography, the director has documented the advancements in how technology can be used voyeuristically as film moved to video, and analogue moved to digital. Passion begins with a large close-up of the Apple logo, seen on the back of a MacBook Pro laptop screen, as Christine and Isabelle watch a promotional video clip. Rather than merely being product placement, this detail is used not just to ground the film specifically in the present time but also to anticipate that social media technology in its various forms is going to be an essential thread woven throughout the narrative. Whereas Crime d’amour only vaguely illustrates the business that Christine and Isabelle are working in, Passion brings it to the foreground. The characters now work for an advertising agency and their latest assignment is the marketing of a smartphone. The “Ass Cam” clip that Isabelle creates for this purpose is modelled after a real web video that De Palma discovered during his research for the picture. The original clip was posted online unbranded and was seemingly created for fun by two attractive young women. It was later revealed that they were actually actors and the video is part of a Levi’s jeans marketing campaign.This type of technology later becomes very important in Passion as it is self-servingly employed by several characters to discredit the film’s only sympathetic character, Isabelle. In a series of particularly difficult-to-watch sequences, Christine coaxes her into a breakdown. After discovering that Christine has video footage of her and Dirk having sex, Isabelle leaves her office in a fragile state and crashes her car in the office car park. This incident is the final straw for her and she collapses weeping and screaming. This intensely private moment is captured on security camera and Christine plays the footage at a crowded work gathering. While Isabelle tries to hold onto her dignity, Christine mockingly says: “This really hurt you, didn’t it? I’m so sorry, I just thought we could laugh together“.

Further into the story, Isabelle discovers that her assistant Dani followed her movements on the night of the murder and captured everything on her video phone. In due course, the clearly unhinged Dani intimidates Isabelle into a sexual relationship in return for keeping the footage from the police. By being abused, humiliated, manipulated and blackmailed with technology that is readily available to anyone, Isabelle is a thoroughly modern film noir heroine for the 21st century.

Since Passion centres on rivalry within an enclosed business world milieu, De Palma forgoes the more elaborate camera movements and spacious use of exteriors often associated with his work to focus on the restricted interior spaces that the characters inhabit. Most of the drama unfolds within the confines of the workplaces, living quarters and social events that Christine and Isabelle frequent. To reflect these stylish environments, the cinematography of José Luis Alcaine is crisp in texture and muted in its carefully selected colour scheme. Replete with glass and reflective surfaces, the imagery possesses a steely quality that many reviewers have mistaken for HD, but it was in fact shot on 35mm. This coldness is further enhanced by blue being the predominant colour, creating a deceptive feeling of calm and order beneath the shiny veneer. Reds are sparsely used but dazzlingly intense and aggressive when they erupt as ruby lipstick or stylish designer stilettos, all signifiers of antagonism in workplace warfare. With this aesthetic and De Palma’s rigid precision of blocking, the framing feels clinical and ultimately imbues this cutthroat domain with claustrophobia.

De Palma has a masterful ability to fill a frame with multiple visual elements, yet he can still balance conveying essential narrative information with details that enrich the film as a whole. His use of the split diopter lens, which allows for the image to display separate depths of field in one shot, is relatively restrained in Passion yet is subtly effective in what it achieves. In one sequence there are three points of focus in a single shot. Dirk lies in bed smoking a cigarette. He is framed in the foreground on the left hand side. In the background, Isabelle stands in the bathroom with her back to the camera. Isabelle’s face is reflected in a large mirror, while other ornamental objects are either situated on the bathroom counter or seen as reflections in the mirror from the other side of the room. In the dialogue exchange between the two characters, Isabelle learns more about Dirk’s relationship with Christine, and discovers Christine’s adventurous sex life which includes a variety of sex aids including a strap-on and a Venetian carnival mask modelled on her own features. This sequence runs a little over two minutes, but within this limited amount of time De Palma conveys the interior design of Dirk’s home which reflects aspects of his personality (an ornament shaped like a penis, a sculpture of an obedient dog), Dirk’s contemptuous attitude towards Christine (“Whatever Christine wants, she gets“), Isabelle’s inquisitive nature (“What’s it like with her?” she asks before rooting through a drawer full of sex aids), and the toys that Christine uses with Dirk that reflect dominance (the strap-on) and narcissism (the mask).

While the split field diopter is an understated way of including an array of elements within a single image, split screen is a more obviously overloaded technique since it simultaneously presents two frames side-by-side. In Passion there is a seven-minute split screen sequence. The left of the screen depicts Isabelle attending a performance of The Afternoon of a Faun, capturing both her eyes watching this ballet and what is taking place onstage. Throughout the music from the ballet, Prélude à L’après-Midi d’un Faune by Claude Debussy, plays while a male dancer (Ibrahim Öykü Önal) and a female dancer (Polina Semionova) perform on the stage. The set dressing is stark and minimalistic, and both dancers play to the camera throughout, constantly meeting its gaze (and therefore, that of the viewer). De Palma covers most of this performance in wide-shot, but occasionally cuts or zooms into the action for tighter frames. This changing of image size often relates to not just the context of the ballet, but also what is taking place on the right of the screen: the build-up to and eventual murder of Christine. It begins with Dirk drunkenly trying to talk to Christine as dinner guests are leaving her home. She escorts him from the house and comes back to find a note on the door stating ‘Leave the door unlocked, undress, shower, blindfold yourself and come to bed‘. While Dirk attempts to drive his car (but crashes it) and Christine prepares for her mystery guest, a figure (whose point of view is adopted by the camera) enters her home, moves up the staircase, sees Christine checking her appearance in a mirror, then hides behind a door which is ajar. Through it Christine can be seen putting on the blindfold and making her way down the hallway towards the figure. The door opens and Christine is gently shoved up against the wall. A gloved hand pulls away her blindfold and she looks directly into the camera – at her murderer’s face. The split screen display disappears as the film cuts to a shot depicting what Christine sees – her own Venetian mask as worn by this figure. Cutting back to her reaction, Christine’s look of surprise turns to fear as the figure’s other hand produces a knife and slashes her throat. The blood splatters into the camera frame, and the scene ends with a shot of the white mask sprayed with blood.

In displaying two simultaneous passages of action, De Palma allows for a sequence that works purely on an visceral level. A familiarity with Jerome Robbins’ The Afternoon of a Faun ballet is not necessary since the precise editing, audio shifts and changing camera frames achieve a disorientating, yet never confusing, juxtaposition of visual and audible activity. The final split screen moment when the female dancer and Christine are each framed attractively in portrait is unnerving. That both are looking into the camera (therefore making direct eye contact with the viewer), one in the midst of performing a beautiful ballet piece and the other about to face her death, is disarmingly effective. This moment of calm is shattered by the passage from the split screen to a close-up of the Venetian carnival mask, and the Debussy music is abruptly cut short with a sharp sting from Pino Donaggio’s dramatic score.

While the treatment of the material may differ between Crime d’amour and Passion, the first half of both films follow essentially the same storyline before going off in different directions. In Corneau’s film, Isabelle is seen meticulously planning the murder of Christine, planting evidence that initially makes her a suspect but later exonerates her, and ultimately frames Philippe (the original ‘Dirk’ character). Corneau’s picture maintains its poise as a refined chamber piece to the end.

In De Palma’s version of events, Isabelle carries out the crime in the same scheming manner. But Passion withholds the identity of the killer until its final scenes, significantly altering the emphasis of the narrative. To achieve this shift, the director reflects the seemingly fragile emotional state of Isabelle (betrayed, abused, heavily medicated) in the increasingly expressionistic form of the film. Sequences begin to play out as groggy dreams within dreams, or as exaggerated recollections of events experienced but now played out in a nightmarish world of tilted Dutch angles and exaggerated faux-noir shadows. As it is ultimately revealed that Isabelle is not innocent and the whole ‘wrong man’ section was, in fact, deceiving the audience, De Palma transforms the material into a meditation on guilt, and the dream logic becomes even more delirious, replete with doppelgängers, browbeaten detectives and vengeful siblings.

Brian De Palma’s Passion came to town last Saturday for a surprise weeklong run at the Music Box Theatre, and continues through the weekend as a midnight show. I caught up with the film the other night with an audience of 15 or 20 (the Music Box’s main auditorium hadn’t felt so cavernous since that midnight screening of Beyond the Valley of the Dolls a few months back), and I was surprised not to have seen more people in the room. The movie finds De Palma at his most playful (or grandiose, depending on your point of view) since Femme Fatale—it’s the sort of movie his fans usually eat right up. (I’m not even a De Palma fan, and I had loads of fun watching it.) As for what the movie’s “about,” allow me to recycle this passage from Jonathan Rosenbaum’s 2002 Reader essay on Femme Fatale, as it applies equally to Passion:[It’s] as if [De Palma] set out to combine every previous thriller he’d made in one hyperbolically frothy cocktail. So we get split-screen framing; bad girls; sweetie-pie male suckers; verbal and physical abuse; lots of blood… lyrically rendered catastrophes; noirish lighting schemes favoring venetian blinds; it-was-all-a-dream plot twists; scrambled and recomposed plot mosaics; obsessional repetitions of sound and image; pastiches of familiar musical pieces; nearly constant camera movements; and ceiling-height camera angles. Best of all, we often get several of these things simultaneously.

I’m not sure if De Palma himself considers Passion to be “about” anything. In the movie’s most impressive set piece, Noomi Rapace’s character watches a ballet production of Afternoon of a Faun while, on the other side of the split-screen, her business rival (Rachel McAdams) gets murdered in a characteristically (for De Palma) elaborate way. Is the filmmaker equating his filmmaking with more abstract arts like symphonic music or dance? (The title would seem to suggest as much.) De Palma has repeated certain motifs so many times that they no longer refer to anything besides themselves. Passion often seems to be after the sort of formal purity that Keats saw in his Grecian urn, with the qualities listed by Rosenbaum serving as De Palma’s clay.

Many of the compositions exhibit classical virtues of symmetry and opposition. De Palma regularly dresses the dark-haired Rapace in all-black and the blonde McAdams in white or red. Even before De Palma starts introducing preposterous coincidences and double crosses, the characters register as doppelgangers—Rapace’s flat underplaying seems intended to compliment McAdams’s exuberant hamminess (which is a hoot, by the way). Likewise, the women’s professional rivalry—a totally arbitrary power struggle within a multinational advertising firm—is underscored by intimations of sexual attraction. Once De Palma establishes these basic oppositions, he goes wild finding different ways to recombine—and re-double—them. When McAdams’s character confesses to having a twin sister, it feels inevitable.

Passion is a superficial film, but not an empty one. Amidst in the visual motifs, De Palma manages to touch on the following themes: corporate power, advertising, sexual desire, sadomasochistic relationships, and longing for love. The movie doesn’t offer a coherent statement about any of these subjects, though De Palma interweaves them with a musicality comparable to his visual style. There’s an odd poignancy to those moments where the themes related to dominance intersect with those related to vulnerability, suggesting that the pursuit of classical synthesis carries the risk of annihilation.

The fact that Brian De Palma in 'Passion' not only beckons Hitchcock but also Fritz Lang, is of course primarily due to the basic intrigue he borrowed from 'Crime d'amour' (2010), the ultimate film by the French director Alain Corneau. Corneau's admiration for Lang was already apparent in one of his first films, 'Police Python 357' (1976): a gloomy police officer driven by a Langian destiny mechanism. In it, the cop on duty (Yves Montand) conducts an investigation that must inevitably lead to his own indictment of a murder that he did not commit.In both 'Crime d'amour' and 'Passion' there is a plot twist that also formed the premise for Lang's last American thriller, 'Beyond a Reasonable Doubt' (1956). In it, the protagonist himself fabricates the burden of proof against himself in the hope of exonerating himself with a coup de théâtre. De Palma is of course more Hitchcockian than Langian and his free remake of a French film is therefore based on Hitchcock's favorite motif of deduplication, which in 'Vertigo' (1958) was pushed to the extreme - abstract and quasi-geometrical.

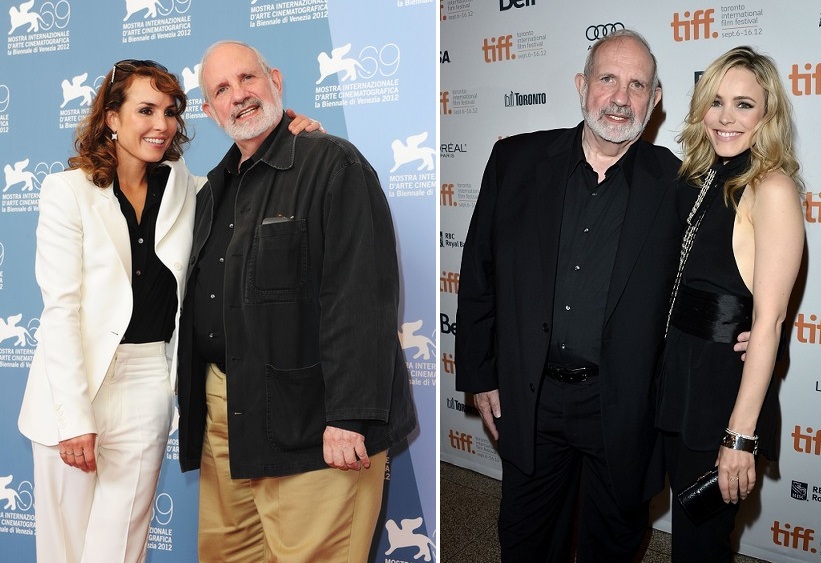

'Passion' largely takes place in a Berlin advertising agency where three young she-wolves are at each other's throats, initially in a quasi-civilized way, but becoming increasingly predatory and aggressive. Women who differ greatly in ranking in the company but are completely interchangeable when it comes to gluttony, desire and greed. Initially everything revolves around the power games between blonde bitch Christine (Rachel McAdams) and her seemingly innocent, dark-haired protégée Isabelle (Noomi Rapace) to whom she gives an expensive scarf as a gift but also steals her ideas at the same time, which Isabelle hits back at. Isabelle, in turn, also has an assistant (Karoline Herfuth) who does not go unnoticed and eventually gets a bigger role in the plot twists than her initial screen time suggests.

Power, eros, humiliation and sadomasochistic strategies in the executive suite have been widely covered in Hollywood, from forties melodramas with Joan Crawford and Barbara Stanwyck to the controversial Demi Moore vehicle 'Disclosure' (1994). The environment in which the clever ladies from 'Passion' maneuver was certainly not chosen by chance: the most critical American director of his generation sees the advertising agency as the quintessence of neo-capitalist lust for power where the desire to dominate the other and thus also the taking over the identity and body of the other, takes extreme forms until one woman Persona-like transitions into the other.

Here, De Palma also makes maximum use of the shiny, reflective and transparent architecture and dynamism of the new Berlin, where an artificial high-tech visual delusion has been created on the ruins of a guilty and criminal past of double dictatorships (the filming locations are mainly situated in the former East -Berlin and the former no man's land between east and west: Frank Gehry's DZ bank, Helmut Jahn's Sony Center and the eerie-looking new building in the residential embassy district).

Above all, De Palma amuses himself with his mise en abîme of a world of visual constructions. For decades, De Palma has portrayed our world as an arena of screens in his films. In this new Berlin, the multiplication of screens as Lang prophetically announced them in the 'Dr. Mabuse' films that appear in the three periods of his German career (the silent film 'Dr. Mabuse der Spieler uit' 1921-1922; the sound film 'Das Testament des Dr. Mabuse' from 1932; the post-Hollywood film 'Die tausend Augen des Dr. Mabuse' from 1960), became reality. Everywhere there are cameras set up, there are indiscreet glances, people are spied on, recorded, eavesdropped and monitored.

The erotic thriller plot is based on a number of confrontations and exchanges on Skype, conference calls, smartphones, videos thrown on YouTube, evidence captured by surveillance cameras. The result is a destabilizing game of voyeurism and exhibitionism, often intertwined and taken over in some key scenes by the good old split screen technique, in which the screen itself is cut in half so that the choreography of the murder runs parallel (or asynchronously) with a real choreography, L'Après-Midi d'un faune.

In his previous film 'Redacted' (2007), De Palma used an even more disorienting mix of various image types to reveal different layers of subjectivity and objectivity, truth and falsehood, fact and fabrication. Here he uses this strategy for a pure style exercise. For the DePalma admirer, 'Passion' can also be enjoyed as one long walk through the fetishes, obsessions and hobbies of the director who here updates his playful erotic thrillers from the eighties and nineties ('Dressed to Kill', 'Body Double', 'Raising Cain'), complete with the comeback of his regular composer Pino Donaggio who once again delivers a teasing lyrical score.

A film also in which De Palma gives free rein to his passion to bring female beauty to the lens in the most fetishistic way. Only this happens here compared to De Palma's related thrillers in such a purified form that the film also has something skeletal, despite the sensually seductive visuals and camera movements. Exactly: like the late films of Fritz Lang.

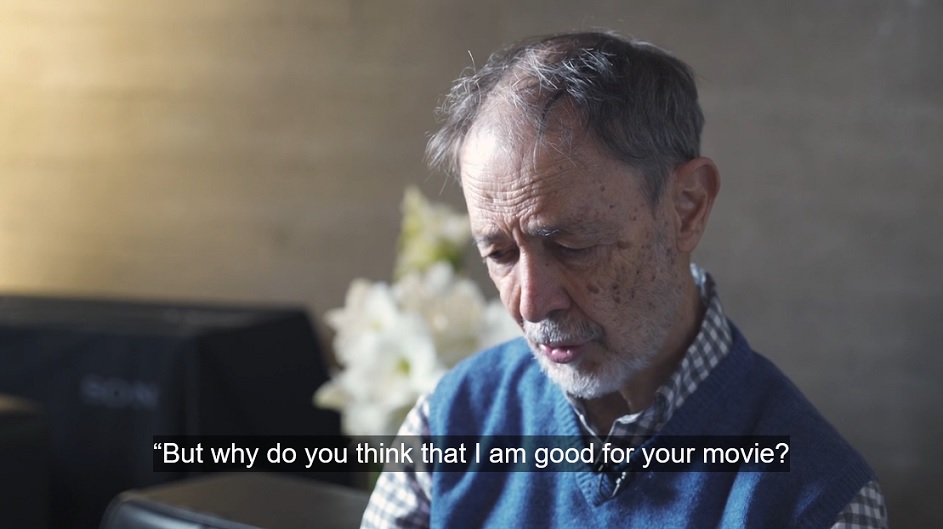

Well, I was born in Tangier, which is a Mediterranean city in Africa. I was a photographer and I studied all the time the light in Tangier. In Tangier, that is something which appealed to me a lot. And with time, something that appears in all my movies. In the year, there is plenty of sun. Sunny, sunny days. So the sun is always inside of the house through the windows. I studied that, and I remember very well the change of the light in the apartment that we lived in. Because in my movies, the sun is always getting inside of the house, through the windows or through anything which can convey some sunlight.There was a question that happens to me… the American director Brian De Palma, calls me for making a movie – I’ve done three with him. On the first movie, I say to him, “But why do you think that I am good for your movie? Because I am not so well known in America.” And he said, “Well, I have seen a lot of your movies, and I noticed that you are always doing – always – very well light. And that is very important for my movies. So that’s why you are here with me.” And I say, “Well, that’s a good reason.”

Most of the time, I don't need to talk too much with the directors I work with. Almost everyone thinks that the director of a film and the cinematographer are communicating during the entire shoot, but in my case it is not true. I need to see the films they have made before, ask them a few weeks before what they are looking for in photography and that's it. Some give me references: 'Go see this film or 'I'm looking for a light like this'... For example, in 'The Bird of Happiness', I asked Pilar Miró what she wanted before shooting. She didn't say anything to me, she just looked in a folder and took out a print of 'The Scream', by Eduard Munch. 'This is what I want'. And from there, one starts to guess.Q. Along these lines, the more accomplished your work is, the less it is perceived by the general public?

A. Sometimes it happens. But what I don't want is for the photography to be noticed. When someone tells me: 'I've seen your film, what great photography', I already know that they haven't seen it or they didn't like what was being told, that's why they paid a lot of attention to the photography. I told Pedro Almodóvar that 'Parallel Mothers' has two readings. One, to see it normally. Another, to see all the details that Pedro has put in and that I have illuminated, because they enrich the film. Perhaps, at the beginning you follow the story and you are not so aware that they exist. In a way, you have to watch it twice.

Q. A book, a painting, a piece of furniture… How do you make those hidden messages visible in Almodóvar's plans?

R. In 'Parallel Mothers', I have basically used very closed diaphragms. [The diaphragm is the part of the lens that regulates the amount of light that enters the camera]. Not only does this mean that less light enters, but the more the diaphragm is closed, the more objects begin to appear in focus and sharp in the shot.

I think that when playing with that, with the depth of field, there can be two types of narration in cinema. There is one that has now become fashionable throughout the world: by opening the diaphragm a lot, almost the entire frame is out of focus, except for a single object or a character that is closer to the camera. That's an advantage for the production of the film, because you don't have to worry too much about what's around you.

The other approach consists of establishing several fields of action that are seen on the screen. The viewer can see them all, first, second, third... All of this enriches the story because there can be different layers of narration. For example, if a character says something in the foreground and another reacts elsewhere in the shot. This allows the viewer to feel inside the place, accompanying the actors. If only one part is in focus, you sit in the chair and see a completely flat screen. For me, it's terrible because the viewer doesn't participate. They tell him a story that is perhaps very interesting, but his vision is very much driven by what the director wants to tell him. He cuts the wings of the story and the relationship. In the cinema that I like, I need more depth of field and a richer image.

P. Where do you think that trend comes from?

R. That started in the 80s and 90s. Many of the important directors of that time came from the world of advertising. The 'spots' that were most popular then lasted about 30 seconds and concentrated many different shots in a short time. And the difficulty is added that they were made for the televisions of the time, which were smaller. That's how they came up with the idea of concentrating the viewer's attention on a single point, on the product, and that's it. For a small screen, that's fine. But for a screen like this [points to the theater canvas], the viewer is out of the game because he only pays attention to a very small portion.

I think that in these circumstances, even if the stories are good, they don't leave a mark because they don't let you participate. They are flat and unrelieved exposures. Within a quarter of an hour, you've forgotten. For the record, all this is a theory of mine… It is difficult to verify. I think that the cinema of the 40s to the 70s left a mark on you, because the relief of the narration was very careful. The tendency to simplify it has to do with an easy cinema, faster to produce in this sense and cheaper, because everything that is outside the field does not matter. It is an orphan cinema. We are at a crossroads. On the one hand there is covid, which drives viewers away from theaters. On the other hand, there is the orphanage of films that leave a mark on you. One of these that makes you want to debate when you go out.

P. Is this audiovisual bill that simplifies the viewer's gaze, or does it happen the other way around?

R. A significant thing happens. This fashion for shallow shots means that the manufacture of new camera lenses concentrates on producing very beautiful blurs. I know that the big companies look for them, because I know some manufacturers. I have asked them about the new lines and they answer the same thing: they are looking for the out-of-focus part of the image to be very beautiful because that is what people ask for. It is the whiting that wags its tail. It seems like a mistake to me, but this covers us all.

It's the same with mobile phones. That of the 'bokeh effect' or the 'portrait mode' is increasingly taken care of, because people like to see themselves. That's why the rest is blurred, so that the portrait focuses on you, logically. I think this can go beyond aesthetics... There is an invasion of images of ourselves, of ourselves and of our friends. Never before have we been so aware of the passage of time on our image. Before, people were not aware of their own aging, of the passing of the years on themselves. Now we take pictures of everything, we see each other when we are 18, when we are 30 and when we are 50. There was a great guy, Rembrandt, who took self-portraits from when he was very young until he was very old. He painted the passage of time, as we do when we see ourselves grow old in the images.

I think this has something to do with the growing cult of image, beauty and, above all, youth. Wouldn't it be better if instead of staying young with surgeries, we stayed young by learning, going back to college? (Laughs).

P. You usually say that the first time Brian De Palma called you to order the photography of a film, it was because he admired your way of portraying the faces of actresses. That is something that is also seen in his filmography with Almodóvar.

R. This is where theater is opposed to cinema, although they are branches of the same tree: in the actors' gaze. The theater actor works with the body and with the voice. But the film has to work a lot with the look. The eyes are very important to express... If the story is impregnated with the gaze, it is taken to another level. I think it's something that can be seen in the eyes of Antonio Banderas in 'Pain and Glory'.

I say that cinema and theater are the branches of the same tree, that of the represented story. I think there is something that we forget sometimes. For me, cinema is form, to a large extent. The interpretation and the story are very important, but so is how they tell it to us. What shots are chosen, what camera movements, how is the light, the montage... Normally, that is not analyzed. I note that almost all film criticism comes from literature. The first thing a critic does, normally, is to tell you about the story, to tell you about the cast. But the visual form is not paid attention to. This is normal if one takes into account that there is no teaching about image and representation.

Q. In an increasingly visual world, do we need a kind of 'literacy' of images?

R. Lately I am advocating the creation of an image subject. What is cinema, painting, sculpture... What is everything that has been used as representation in the history of mankind. That, from an early age, students begin to discover what is used to tell stories visually. Right now, there is a large part of the youth that does not read, but almost all of them consume many audiovisual products. Even they themselves, through their networks, create small stories in images. They are taught to read and write, things that fewer and fewer of them do outside of school. A subject dealing with the image through the ages, in all its variants, would be good. Of cinema and television, of course, but of many other things. A painting is also a story, painters tell stories through the image. Students need to know how to analyze this and take advantage of it. Above all, because in our civilization images are constantly used as a means of expression. It's very important.

And this has more implications: a lot of news and many images are falsified. If we do not leave aside the tools to analyze photographs, interpret them and create them, it is possible to be taught to detect these manipulations. We are invaded by the image and it is not a bad thing. Yes, it is a very different culture from the one I knew, much more influenced by literature, but our kids should learn to use the visual and express themselves with it. As we were taught with literature.

P. What can be learned from those codes in the cinema?

R. Many times, visual codes depend on gender. It's true that I haven't worked much on that type of film. Action, superhero, horror... I remember one I did with Chicho Ibáñez Serrador, 'Who can kill a child?' It was a horror film, set on a beach and with some kids as murderers. He gave me the film and I proposed to take a photograph far from the typical horror film. Paradoxically, that the terrifying was in the situation and not in the image, because then it becomes a movie. If you take a photograph of summer and the Mediterranean, people are a little surprised and scared. Because he thinks it can happen to them. Otherwise, the horror genre is full of clichés. I always laugh when the topic of the girl who goes into the alley alone comes up. There's already bullshit there... A girl would never go in there alone! Photography is full of sparkles, backlights, long shadows... In Ibáñez Serrador's film, I tried to escape from the genre in terms of photography. From time to time, he would say to me: 'Hey, why don't we make a shadow on the wall as threatening?' And I told him better not, he's not interested... Besides, with a natural thing, the public is more surprised. If the door creaks and a shadow appears, we already know what will happen.

Somehow, 'The Skin I Live In' also had that point of suspense and terror. But neither Pedro nor I wanted a genre film. We wanted to tell some facts and not know very well what was going to happen. For my taste, what happens in the genre is that what is going to happen is telegraphed, you see it coming if you have a certain visual culture. But if you don't give any indication, people are left baffled. I try to escape codes in lighting.

P. In addition to naturalism, you emphasize the elaboration of light, the creation of volume on the screen. Where does this concern come from?

A. I have a lazy eye. It works worse than the other and, since the relief is given by both eyes, my brain is inclined to pay more attention to my good eye. Because of this, I have difficulty perceiving the volume. I have a hard time seeing things in relief, so I create it with light. The lighting helps me to highlight the volume of things and, incidentally, to correct this defect that I have.

In almost all my works, I start from the idea that I am always learning. I am always looking at everything, especially the innovations that are coming out. Once, I had the idea of using fluorescent lights when it was not usual in the cinema. I needed a flat, low light to illuminate a table with multiple characters. I was thinking a lot about making a wooden one to put several spotlights with a tracing paper on top... Well, a mess. And I thought: 'But this could be a home fluorescent'. So I went with my production manager to a hardware store to buy some tubes and we started using them. In fact, when he had filming outside, he traveled with a trunk full of fluorescent lights, because they weren't used and there weren't any anywhere. Now it's the most normal thing in the world.

P. Sometimes, changes are not well received... You also often say that, when you were studying at the Official School of Cinematography, they told you that cinema was not made for you.

A. Yes. It was for a very simple reason. When I started, what was done was a studio light, with very defined shadows. That seemed a bit false to me and I was always looking for ideas to find another way to light. I did tests of all kinds. In film school, I was considered a dangerous madman. I tried to see if by bouncing the light off a wall or by putting some white paper on some black flags... That's what led Juan Julio Baena, who ran the school, to tell me that the cinema was not made for me. But I didn't pay any attention to him. He was very convinced of what he was doing. When someone is sure of what they're looking for, even if they can't find it, it's hard to keep them from it.

Newer | Latest | Older