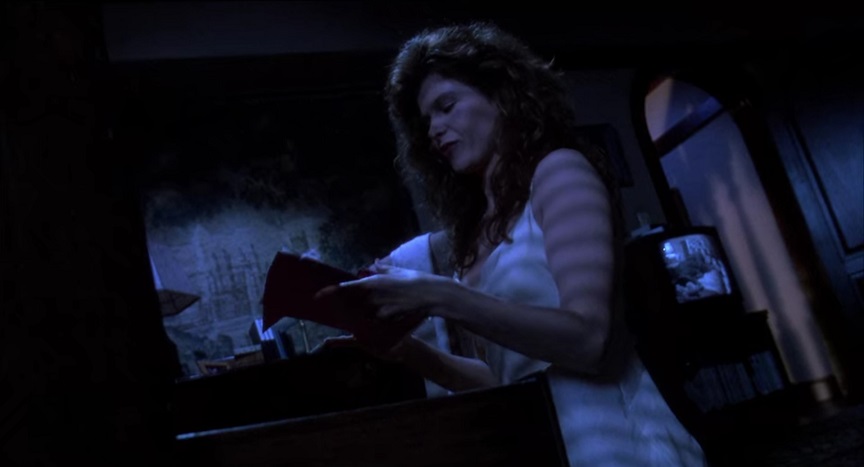

LOLITA DAVIDOVICH AS JENNY - "Yes, can you tell him that Jenny O'Keefe called, and that I have his keys..."

Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | September 2024 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

| 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 |

| 29 | 30 | |||||

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

While the structure of the theatrical cut does take something away from the experience, I would vehemently argue that it still has plenty of merits exactly as it is. So, for the sake of simplicity, I will focus this essay on the theatrical version because it remains the most widely accessible incarnation of Raising Cain. But for anyone keen to track down the alternate cut, Shout Factory has released Gelderblom’s version as part of a collector’s edition Blu-ray.No matter which cut of the film you watch, John Lithgow’s ever-versatile performance is a key element of the picture’s success. The actor shines in his turn as several different characters and personas that live inside Carter’s mind. Lithgow manages to convey a sense of real menace in his turn as Cain, helplessness as Carter, and a level of unhinged fury in his portrayal of Dr. Nix.

Like so many of De Palma’s films, Raising Cain is filled with giallo influences. Although it may not have been De Palma’s initial intent, the theatrical cut sort of functions as an exercise in dream logic. There’s a constant surreal quality to the proceedings that feels reminiscent of the output of Argento and Bava. The inclusion of multiple dream sequences combined with narrative developments that feel very dreamlike make the proceedings a bit chaotic. But given my deep appreciation of the Italian murder mysteries of yesteryear, I don’t mind.

The film is also helped along by a number of signature De Palma techniques, including some beautiful split screen and split diopter shots. Not to mention, the director frequently demonstrates his keen ability to craft tension. The sequence where Jenny believes she’s left a gift for Carter in her lover Jack’s (Steven Bauer) hotel room is supremely suspenseful. The footage is assembled masterfully and paired with a chilling Pino Donaggio score. The exchange serves to keep the viewer in a state of perpetual dread as Jenny sneaks into Jack’s room in the middle of the night. There’s a jump scare associated with this setup that makes me leap out of my skin every time I see it. Even though I know it’s coming, I still react the same way.

Moreover, the picture’s final shot is absolutely phenomenal. The way it’s framed and what transpires within only serves to make me love this film all the more.

As I mentioned previously, Raising Cain is set on and around Valentine’s Day. There are plenty of references to the holiday to make this flick a logical alternative to the obvious choices we revisit each year. Valentine’s Day works as a nice backdrop, giving Jenny a reason to buy gifts for both her husband and her lover. But it’s not a central theme, which makes it accessible all year.

In Raising Cain, Sternhagen was at the center of what is possibly Brian De Palma's most wonderfully outrageous Steadicam shot. Entertainment Weekly's Tom Scanlon was there while they were filming:

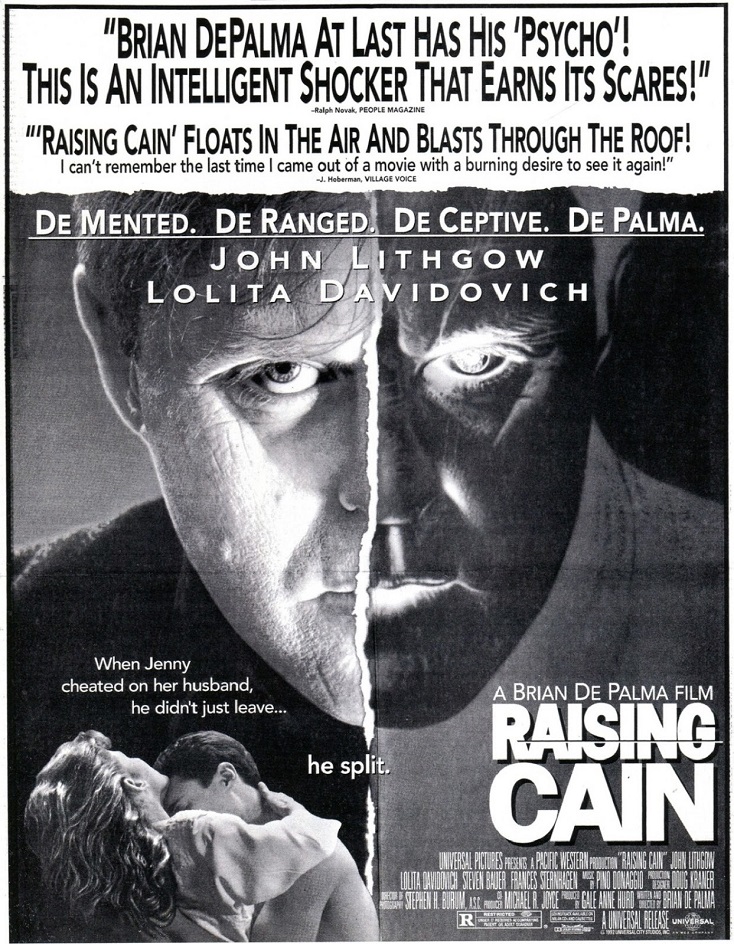

”Cut!” director Brian De Palma calls out. ”Cut, cut, cut,” he mutters, hustling up the steps toward actress Frances Sternhagen. The stocky, salt-and-pepper-bearded De Palma is known for his on-the-set gruffness, but here he shows a softer side, gently coaxing from Sternhagen (Misery) the inflection he imagines an elderly Swiss psychologist would have while explaining how a harmless family man could harbor multiple, murderous personalities. Shooting at City Hall in Mountain View, Calif., De Palma wants Sternhagen to deliver the complex speech while following a pair of detectives through a hallway, down a flight of stairs, onto an escalator, and into an elevator, finally ending up in a basement morgue — all in one continuous shot.The scene is almost as long as the 4-minute, 50-second Steadicam shot that opened De Palma’s last picture, The Bonfire of the Vanities (1990). But if the controversial director of Dressed to Kill, Scarface, and The Untouchables has his way, that will be the only similarity between the two films. With a lean budget ($12 million), relatively low-profile leads (John Lithgow, Lolita Davidovich, Steven Bauer), and a low-key production in the suburbs of San Francisco, Cain is not only a return to the Hitchcockian terrain where De Palma has always felt most at home but it’s also his chance to prove that he can still craft an efficient thriller.

The Cain script, which De Palma also wrote, gives him an opportunity to indulge his taste for showy plot twists and frequent nods — part homage, part send-up-to the master. And it gives Lithgow (Ricochet) the chance to let loose an entire improv troupe’s worth of kinky character studies. ”I must say, I’m great in this movie,” Lithgow chuckles. ”This is going to be mind-blowing.”

For De Palma, who had recently married Terminator producer (and James Cameron’s ex) Gale Anne Hurd, keeping the project manageable was a top priority. ”Gale was pregnant (she has since given birth to a baby girl, now 10 months old), and I wanted to do a movie that I could do very simply and that was close to home,” he says, adding that he deliberately chose locations that were near the couple’s Woodside, Calif., home. Hurd, who’s also Cain‘s producer, says, ”It’s really nice to be able to go to sleep in your own bed.”

Particularly on days like this. The long Steadicam shot requires 27 tedious takes. In the final seconds, with actors gathered around a covered body in the morgue, De Palma bellows stage directions.

”Hand!” he shouts, directing the coroner to lift the corpse’s bloody hand.

”Drop!” The hand drops back on the slab.

”Face!” The sheet is yanked back to reveal …

Interviewed by Charlie Rose in 1992, just three months after Raising Cain was released, Rose asked Sternhagen to explain what she measn when she says that she works from the outside in:

Well, it really means that I like to… I feel like John Cleese, the man of silly walks [laughs]. I like to find out how it feels to walk and talk like a character before I really start on the emotional moments. … It begins to all happen together, but in the very beginning, it starts – I love things where I have to do accents, for example. It’s a kind of limit. It’s a kind of pattern that I then can fit myself into. And I know I have a friend, for example, who has no idea that I used her in a movie. And what I loved about it was I just – it began to happen. As I read it, I started seeing how [voice trails off], and pretty soon, I found myself being tough and hard, just the way she was. And what was wonderful was that, I got a little apprehensive that she might recognize herself, she came up to me after seeing the movie and she said, “I like that character you played!” And I thought, she likes herself. She likes herself, that’s nice!

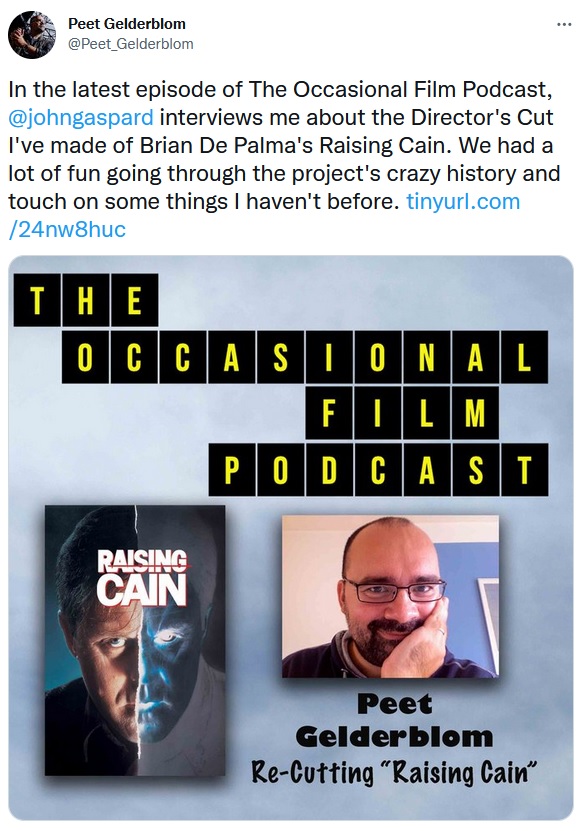

I am very happy that Peet Gelderblom was able to piece together a version of Raising Cain that followed the supposedly even more non-linear structure of De Palma's original screenplay. However, I have always loved the film for which De Palma brought in Paul Hirsch to help edit into gonzo shape, and that was originally released in theaters in 1992. Bloody Disgusting's Daniel Kurland seems to prefer Gelderblom's recut:

Brian De Palma is an absolute master visual storyteller and his movies are always cinematically stunning even when they don’t fully work as films. For every Carrie and Blow Out there’s a Snake Eyes and The Black Dahlia, but Snake Eyes still kicks off with a twelve-and-a-half minute unbroken tracking shot and Black Dahlia turns the camera into an airborne omniscient spectator during its dynamic gangland shootout and simultaneous corpse discovery. 1992’s Raising Cain comes at an important period of transition for De Palma. Sandwiched between The Bonfire of the Vanities and Carlito’s Way–ostensibly the two extremes of De Palma’s career–it’s easy for Raising Cain to get lost in the shuffle despite its completely gonzo nature and scenery-chomping performance from John Lithgow.Raising Cain is the story of Dr. Carter Nix (John Lithgow), a revered child psychologist who experiences a mental break and struggles to stay in control when other identities fight for authority. A hostage in his own body, Carter heads down a dark path that endangers his entire family while he relives his painful past. Raising Cain, for decades, was criticized for its confusing construction and was even viewed by some to be De Palma’s attempt at satire of his tried-and-true genre of choice. In reality, Raising Cain is an earnest–perhaps too earnest–movie that’s been misunderstood for a different reason altogether. Now, on its 31st anniversary, Raising Cain has become even more fascinating on a meta-narrative level. The film has turned into this bifurcated, jumbled experience that tries to messily reconcile many different ideas and tones at once through its two exceptionally distinct edits, like Carter’s own fractured psyche.

Seasoned De Palma fans will recognize how Raising Cain plays all of the director’s trademark hits, but those who aren’t already into De Palma’s style and aesthetic will have little to connect with in the heightened movie. It’s definitely a polarizing De Palma title, even for the hardcore fans, but Peet Gelderblom’s “director’s cut” edit does deliver a better version of this movie that creatively plays with non-linear storytelling. This might have been confusing in the early ‘90s, but audiences would learn to love this structural technique only a few years later with Pulp Fiction and Memento. It’s curious to consider how this avant-garde approach, if left undisturbed, might have come across as revolutionary rather than confusing, which was the fear. The theatrical cut attempts to bury, hide, and normalize these unique flairs–not unlike what’s done to Carter to smooth out his wrinkles so that he’s the most conventional, boring, mainstream version of himself. It’s another powerful, albeit unintentional meta element to Raising Cain that still rings true and makes the story behind the film and its two separate versions almost as interesting as the movie itself.

The divergent responses to the two cuts of Raising Cain emphasizes the “power of the edit.” The theatrical cut of Raising Cain, while chaotic, still led to a sect of audiences who believed that it’s meant to operate on dream logic and that it’s not supposed to make sense. The belief is that it’s ludicrous that De Palma has done so many better versions of this type of movie and that the audience knows that De Palma knows better. This dream logic rationale to Raising Cain’s theatrical cut may work, but it wasn’t De Palma’s original intention. Nevertheless, two complementary and contrasting movies can be born out of the same story, all depending on how it’s told and its dominant perspective. It would have been better if De Palma’s original vision could have made its way into theaters, but if any of his movies needs to suffer an identity crisis through its edit then it’s at least appropriate that it’s Raising Cain.

Raising Cain is dense with De Palma’s typical themes of dishonest women, overbearing fathers, and unhealthy familial relations between the three. It’s hard not to think of De Palma’s own frayed relationship with his doctor dad when Carter gets abused and mocked by his father, even if De Palma hasn’t acknowledged the connection between the two himself.

Raising Cain is hardly the first of De Palma’s movies to relitigate the same layered questions of identity that Alfred Hitchcock first unpacked in Psycho. Both Sisters and Dressed to Kill are De Palma’s previous attempts at dissociative identity disorder in one way or another, all of which are quite tone-deaf and ignorant on the material even if there seem to be good intentions. It’s important to understand that Raising Cain is very outdated when it comes to understanding Carter’s diagnosis. Raising Cain shouldn’t be viewed as an accurate, or even sensitive, portrayal of this condition. It’s a heightened boogeyman that operates in plain sight. Accordingly, there are shades of Dressed to Kill, Sisters, and Psycho in Raising Cain. The exceptional final shot also riffs on one of the scariest moments from Dario Argento’s Tenebre. However, more than anything, Raising Cain comes across as the synthesis between Body Double’s lurid thrills and Femme Fatale’s labyrinthine dream logic. Raising Cain is the messy stepping-stone between both of these more fully-formed movies that all riff on comparable themes.

Before chatting with you, I sat down and rewatched both versions and took notes to try to figure out what the order was. And what throws it off for me a little bit is the opening shot in the theatrical cut of the park from high up is very much a Brian DePalma opening shot, you know, very close to what he did in “Carrie.” Whereas, the opening shot in the clock store is not really a DePalma shot. It's a little mundane. It's a wide shot. It's interesting, you know that Jenny walks up and sees herself in the heart shaped camera and all that--Peet: It encapsulates the whole movie, but that's in a different way than the original did.

Yes, exactly. And then as I was going through—and I'm sure you ran into this, it's regardless of whether it's the re-cut or the theatrical one—it's a dream sequence with a flashback built into it. And so it isn't until you get out of the dream sequence that you realize, oh, that was a dream sequence. But then in your mind, you're going well, then, was the flashback real, or is that part of the dream?

And then they've added in narration as part of the flashback to help explain it, which I'm guessing was done in post. And so now they have a narration thing. So they have to keep that up. And then when they switch it around, when you did the version that was closer to what he wanted, it's still a bit wonky, regardless of whether you're chronological or not. And the audience has to go: okay, she's going to the hotel. Is this a dream? It must be a dream, because she's walking into the room and she doesn't have a key. That's the only clue, I think, that it's really a dream. And then obviously it's a dream, because she's killed and wakes up. And then you have the repeat of the thing with the gift and all that.

So, regardless of the order of everything before, that whole section, I think is always going to throw an audience off.

Peet: You're right, but the wonkiness, if you call it that, it is intentional. What he wanted to do, and he has stated this in interviews is, you know, normally with kind of police mystery, there is something going on and you don't know quite what. And then the detectives, they start to ask around. And you slowly assemble information, and it becomes clearer and clearer what actually has happened. And he really wanted this time to fuck with his audience, of course, because that's what Brian DePalma does. And he said, what if all the information the audience is getting is either a dream, it has never happened? Or they don't know if it's happened. Or, you know, it's an unreliable narrator. That was actually the game.

And he's so good at that.

Peet: He's really good at it, but of course you also need to get the audience so far that they're willing to go with you. Because it's a very manipulative way of telling a story. And some people don't like that. So, that's a very thin line that he was walking.

And I think in the editing, he got cold feet. He thought, well, maybe I went a little too far here, and maybe I should do it a little differently, help them out and make everything chronological, and it may have fixed some things. But it created other big problems. The flow isn't really right. It wasn't how he originally imagined it.

Gale Ann HurdFilm and TV producer, including The Walking Dead franchise

What I was doing in 1992 Brian de Palma and I were in post-production on Raising Cain, which we filmed and posted in the Bay area. I was also in post on The Waterdance, written and co-directed by Neal Jimenez, which premiered at Sundance and won the Spirit for best first feature (over Quentin Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs!). I was coming off Terminator 2: Judgment Day, which was the world’s top-grossing film at the box office, and had an overall deal with Universal Pictures.

Most memorable challenge Juggling motherhood — my daughter was born in September of 1991 — and my career, [a challenge that] continued until my daughter went off to college.

Progress that women in entertainment have made It isn’t as rare to see women succeeding as producers, directors and writers, but the industry still isn’t a gender meritocracy.

Advice for new women on Power 100 Your perseverance is as important as your talent.

My family rented Raising Cain under the pretense of a dark thriller. I vividly recall about 20 minutes into the film, when the aptly-named character appeared, those in my household grumbled. Not because having two Lithgows for the price of one is a bad deal, quite the opposite! The family didn’t understand what was going on. Why is John Lithgow talking to another version of himself? A young kid like myself didn’t get it either, but I was willing to soldier through. Unfortunately for me, my family felt otherwise and shut it off around the time Cain and Carter’s dad makes himself known. Of course, who played the father? You guessed it, John Lithgow. My parent packed the movie and shipped it back to the video store. Did we get our money back? Of course not: we rented Alien 3 instead. I feel that was the wrong decision.Anyway, Raising Cain holds a memory; I won’t say it was special. I watched it years later and found it a decent De Palma film with an excellent performance from John Lithgow. It doesn’t reinvent the wheel, and everything you love (and hate) about Brian De Palma is in Raising Cain.

The second interview, “The Man In My Life,” is a sit-down with actor Steven Bauer. As with Lithgow, Bauer talks about the attention to detail that De Palma brings to his films by telling a tale of seeing the entirety of Scarface‘s production storyboarded in his office. From there, Bauer discusses going through a divorce and his relief—having to work on the set of Raising Cain to take his mind off his marital issues. While “The Man In My Life” isn’t in-depth on the day-to-day workings of the production, it works as a window into the mindset of Steven Bauer. And that is just as entertaining and informational.“Have You Talked to the Others?” is an interview with editor Paul Hirsch. Hirsch traces his career back to the early ’90s working as an editor-for-hire to make “terrible films” into “bad films.” I appreciate Hirsch’s honesty as he talks about his first brushes with the film and not understanding what was going on in the script and what Brian De Palma needed. A funny story comes about as Hirsch details De Palma watching him edit while reading a book about ways to commit suicide. While short, “Have You Talked to the Others?” is one of my favorite interviews due to Hirsch’s openness.

Gregg Henry sits down to talk about his time on set with “Three Faces of Cain.” Speaking for myself, I love and appreciate character actors. Gregg Henry is one of my favorites, and I was excited to hear his thoughts. As is a recurring theme throughout the interviews, Henry talks about how De Palma maps out the film and comes to the set prepared, understanding how the film is to look. Henry talks about the infamous one-shot sequence and recounts a horror story about one actor blowing his line at the end of the shot. While there’s nothing earth-shattering in the interview, Henry speaks highly about the production, is proud of the film, and appreciates all involved.

Actor Tom Bower is next with the interview, “The Cat’s In the Bag.” Bower talks about working on the one-shot with Henry and actress Frances Sternhagen and the reviews he got for his work on the production. There’s not a lot with this interview, but it’s a cute addition and worth checking out at least once.

The last interview on the theatrical cut disc, “A Little Too Late for That,” finds actress Mel Harris discussing her work on Raising Cain. Harris heaps praise on De Palma for his professionalism, what drew her to accept her role as Sarah and working with actress Lolita Davidovich. It’s nice to see Scream Factory reaching out to the supporting players, giving them time to share their thoughts, and Harris is no exception.

Newer | Latest | Older