So much of this film takes place “inside” a cellphone, so to speak. Is it an iMessage movie? I had the desire to make a movie that was simply one long conversation over text messages. That’s a bit of a stretch, and would get us into some kind of experimental area, which is not quite what I wanted. But I think that text messaging — which has become such a big part of our lives, for such a long time now — is a fascinating mode of communication. I think its potential has never really been fully explored in films.

How do you mean?

Because texting creates a relationship to words, to punctuation, and other very complex things — how long it takes to answer, how it feels when you’re waiting for an answer. It’s so complex, and it’s so charged, and the way we use the words is so careful. It’s very similar to poetry. Texting is the closest thing we have to poetry in everyday life — because all of a sudden every single word echoes in all of its meanings. It’s very complex. And also fascinating, because we have this strange and disturbing addiction to the screens on our phone. It’s mesmerizing; there’s something hypnotic about it.

What exactly is so engrossing?

I think that any kind of text conversation is pretty intense. And it’s more intense than actual live conversation, which is mitigated by politeness and social conventions. Text messages are straight to the point: you verbalize things in a much clearer, straightforward way than you would do in conversation, where you sort of wrap it in niceness. In text messages, it’s not wrapped. It’s raw. I always thought there was an intensity there — and we’re not even talking about sexting, which one can do or not do, but when you even get close to that area it’s disturbing.

That’s fascinating dramatically. But what about aesthetically? How did you determine how the texting would look on-screen?

To me, it was obvious I was going to shoot the phones, to have the phone be held and used in close-up. I was not going to have those little pop-ups; I don’t like that at all. Because for me it has to do with the screen. If you disconnect the words from the screen, they don’t function the same way. It’s all about the screen. It’s the screen that fascinates us. Again, if you print the words, you don’t have the icons. You don’t have the waiting, the “received at that time,” you don’t get that kind of suspense. And that’s very specific — and addictive.

We’re addicted to the suspense of waiting for messages to arrive?

To all of it. I realized, you know, even when I was I was shooting the phone footage, and we’d wait for the text to arrive on camera, I would think, is it coming, is it coming? And I liked the idea of movement. A lot of times we have inserts, closeups; some of them we did separately but a lot of them have to do with the movement and the way Kristen is typing. She used to say that it’s a movie where her thumbs are the co-star. The way she types is interesting.

Did you instruct her to put a space before her question marks?

No! She did it naturally. This is something that’s not part of English punctuation — it’s something you do in France. In French, there’s a space.

Oh. That makes sense.

No, it makes no sense! But yeah, I never told her, “change this,” “you misspelled this or that.” I thought that was all part of the process.

I love this idea of turning off airplane mode and having the texts come through.

That was part of the screenplay, yeah. I wanted the fear to rise. I like the idea of the text messages coming as a cascade. But it was difficult to get it right — we had to do it multiple times. And the version in the film, it’s the only moment that’s slowed down. There’s a slight slow-motion.

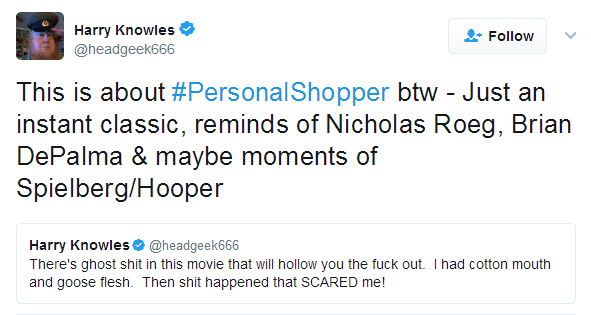

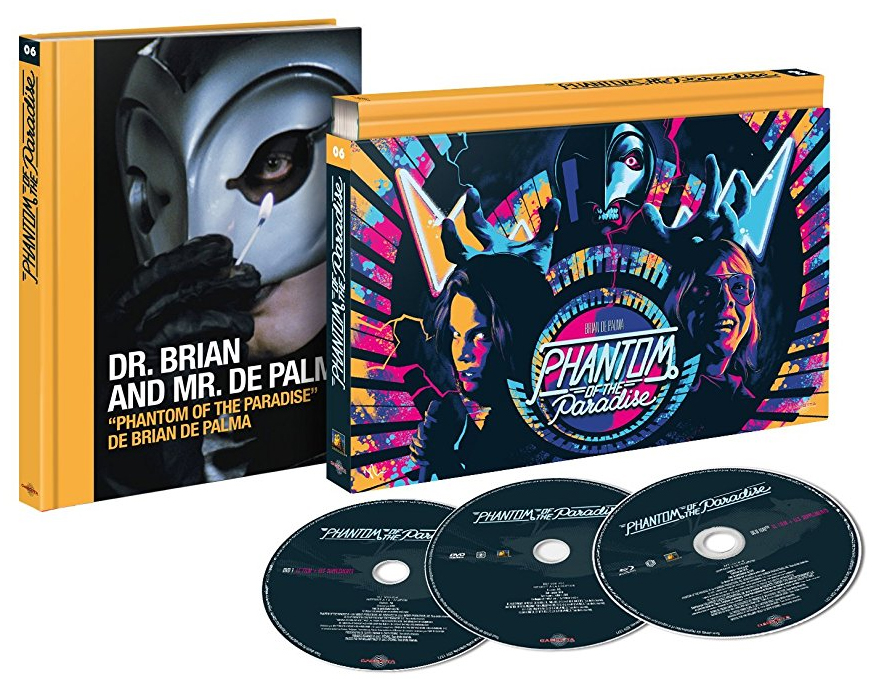

Was Brian De Palma on your mind at all?

I love Brian De Palma. Not so much the recent work, but I’m a huge fan. I’m a huge fan. Some of his Hitchcockian work is pretty amazing. I never interviewed him, but I wrote a long piece about Body Double. I love most of his films from that period. The Fury is amazing.

It was on my mind because of the police interview…

Well, the love I have for De Palma, it’s like the admiration I have for filmmakers like David Cronenberg or John Carpenter. They are guys who make genre films that are just way beyond the genre. They are great artists. Usually they use genre to make films that deal with more complex things. Things that are more powerful. De Palma or Cronenberg, they deal with abstractions, with the mysteries of life. They are just great, great filmmakers, great writers. The genre element just makes it more powerful. So I tried to learn the lessons.

You’ve made genre films before. Boarding Gate, Demonlover. How do you balance those genre elements with a more sophisticated arthouse style?

Well, the more what I have on my mind is abstract — the more it can even be a bit intellectual, but I hope in the better sense, meaning reflexive — the more I feel I need the genre element to make it exciting. But it’s all about the balance. It’s only when you’re writing or editing when you feel the right balance.

Did the balance change in editing?

Yes. The music changed a great deal. Horror movies, they are covered in music, from start to finish, and it’s always very similar. At some point… you know, I’m friends with the Daft Punk guys, one of the Daft Punk guys. I wanted to use his music for the film, to have some kind of electronic soundtrack. And then I realized it would literally destroy the film — because all of a sudden it would become a genre film. That’s when I started using baroque music instead. It’s totally not what you’d expect in a genre film, and it doesn’t give it a genre tone. For me it’s a movie about Maureen that once in awhile goes into genre territory. So that’s mostly where the fine-tuning was. Also the ghost scene. Using CGI, it’s not exactly my world, it’s kind of strange to me. I thought I kind of needed to give some reality to her vision.

Julia Ducournau's directorial debut, Raw, opened a couple of weekends ago. Several reviews have mentioned Brian De Palma, as well as other filmmakers, as potential influences, and specifically De Palma's Carrie and Sisters, in relation to Raw. In the first link/excerpt below, Ducournau explains to Dan at Geekadelphia why Carrie was the only consciously deliberate reference she made to any film. Following that are links to other reviews of Raw:

Julia Ducournau's directorial debut, Raw, opened a couple of weekends ago. Several reviews have mentioned Brian De Palma, as well as other filmmakers, as potential influences, and specifically De Palma's Carrie and Sisters, in relation to Raw. In the first link/excerpt below, Ducournau explains to Dan at Geekadelphia why Carrie was the only consciously deliberate reference she made to any film. Following that are links to other reviews of Raw: Hot on the heels of

Hot on the heels of