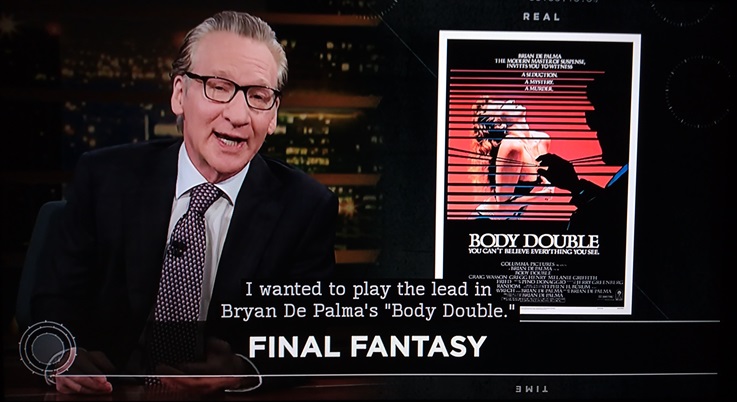

“It wasn’t a box office smash and it wasn’t promoted heavily or endorsed by critics at the time,” Henry said. “It was not enthusiastically endorsed by the studio. They kept the opening on the down low, you know what I mean? Now, that might be just my opinion. Go talk to the marketing budget people who might tell you something different. But I don’t think so. I think it was pretty understated in terms of the publicity because it was dealing with porn stars and looking at Hollywood in a sort of satirical way. It had all kinds of dark sort of things and Brian could be prickly when dealing with those studio types as well.” That “prickliness” from De Palma was rooted in the mainstream pressure within Hollywood to conform to a particular genre. De Palma, rather, built his auteurism upon commenting on the state of the film industry as a whole rather than succumbing to it.

“I think part of it is what we were just talking about a little bit ago is that there’s, you know, well, ‘How am I supposed to classify this? What pigeonhole can we put this in?'” Henry said. “‘Well, it’s funny but it’s kind of scary.’ ‘Well, it’s just a thriller.’ ‘Well, he said it is like ‘Rear Window.” Just on and on, the way people talk about Brian’s movies.”

According to Henry, “Body Double” has the ideal blend of the “definitive De Palma signature,” AKA it confused critics and studio marketing executives alike because it’s supposed to.

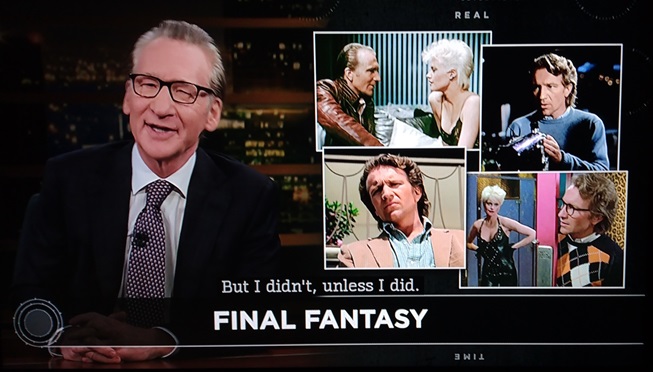

“I think that he had it before that but I think at that point in time, it’s like it becomes this sort of stamp along with the score,” Henry said of “Body Double” being distinctly De Palma-esque. “You can see like, you know, five seconds from across a large room and go, ‘Oh, that’s all pretty unusual.’ I mean, it’s unusual for, like, a singer’s voice or a painter’s paintings or anything.”

The tone of “Body Double” just might be what audience members are trying to unravel. While the film is no doubt a thriller, that’s not where the core tension comes from onscreen. Rather, it’s the toying with parody, power, and pleasure that De Palma deftly explores both with his camera work and script.

“I just think a lot of it is tongue in cheek,” Henry said. “A lot of scenes are humorous and poke fun at the movie business, certainly. It fires off in a lot of directions.”

Like that old Hollywood saying, films that criticize Hollywood don’t ever really find their appreciation in Hollywood. Don’t bite the hand, et cetera, et cetera. Henry finds “Body Double” “still funny” 40 years later, but also is aware that modern audiences may find some of the sequences a little more complex in today’s political climate.

“You watch it with your hand over your eyes,” Henry joked. “It was more fun than anything. It’ll be very interesting actually [to watch the discourse surrounding the re-release]. It was considered racy and dangerous for Brian to be taking this stuff on and doing it in the film. And now it’s racy and dangerous for a whole different reason. But maybe it’s the same reason, I don’t know.”

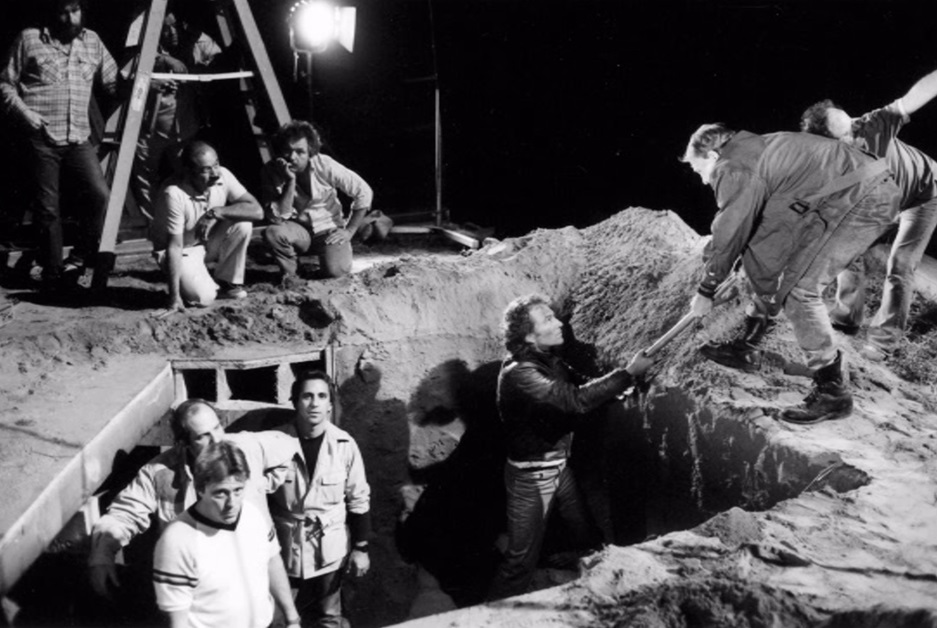

Henry continued, “I think some of the sense of humor might not play but some of the things that are funny to me, that are funny to Brian…I mean, he has that romantic spinning and 360 shot of the embrace which is really difficult to do and he does them really beautifully, with the score swelling. Those things make me laugh, you know. But then I don’t know if they make anybody else laugh. The same with the drilling scene. I just remember we’re talking about which bit we’re going to use and I’m saying to myself, ‘I know Brian’s going to go for that, which is huge,’ and that was the one he wanted. Then we’re shooting it in the blocking of it all. I had forgotten this, but it started with this crazy shot with using the drill horizontally, sort of going like as a sword going into her and everything. Then ultimately she’s on the ground and I said, ‘Well, I know what you want’ and I turned around with the drill and I sat down and started to swing it between my legs [like a penis]. And he said, ‘Yeah, that’ll be great.'”

From improvised phallic weaponry to cinematography Easter egg jokes, it makes sense why “Body Double” proved it could transcend its (or any) genre. “It’s sufficiently scary but it’s also very funny,” Henry said.

In fact, the only other director who can balance that tonal discrepancy between comedy and horror is James Gunn, according to Henry.

“I did James’ first movie, ‘Slither,’ with him, which has a similar sort of sensibility in terms of humor,” Henry said. “James and Brian are really my favorite people as directors.”

Like with De Palma, Henry continued to work with Gunn and appeared in the “Guardians of the Galaxy” trilogy.

As for “Body Double,” Henry couldn’t help but lament on the greatness of De Palma.

“I’m extremely proud to have done a lot of movies with Brian and I’m proud of being in this movie, even though it deals with some dicey and juicy areas,” Henry said. “I think he’s a masterful filmmaker and I think he is a stylist like very few directors are. It’s been an honor to be able to work with him.”