"REMINDS OF NICOLAS ROEG, BRIAN DE PALMA, MOMENTS OF SPIELBERG/HOOPER"

Previously:

Personal Shopper echoes Body Double and De Palma in general

Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | March 2017 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

| 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 |

| 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | |

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

“Having done a lot of reading about Howard Hughes for another project, I found myself wondering what it would be like if a murder took place during a prize fight at a casino,” an unusually loquacious De Palma told [Charlie] Rose ahead of Snake Eyes’ release. “Hughes was always inviting bigwigs to the fights in Las Vegas and talking business. And as I'd grown up in Philadelphia and had seen how the casinos had come to effect Atlantic City, I thought that environment was the perfect place to stage a murder.”

Borrowing liberally from Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo [Editor's note: I think he really means Kurosawa's Rashomon] – in which a crime is viewed from a variety of different perspectives – and pretty much any Hitchcock movie you care to think of, De Palma fashioned a film that’s as big on style as it is small on substance. If the film is ultimately rather frivolous, it’s sure to fascinate anyone who’s either visited Atlantic City or harbours dreams of taking in the wretched hive of scum and villainy.Of particular interest is the flamboyant Gilbert Powell. Played by John Heard of Cat People and Home Alone fame, Powell is very clearly the film’s equivalent of Donald Trump; The Donald being among the biggest names operating in Atlantic City around the time the movie was shot and set. Indeed, as the future president’s Historic Atlantic City Convention Center had played host to WrestleManias IV and V, so the man with the hypnotic hair had brought many a major box-office to the East Coast. Trump would also be instrumental in bringing MMA to Atlantic City, a bold move that led to UFC hefe Dana White being among the more unlikely speakers at the 2016 Republican Convention.

As a snapshot of Atlantic City in the late 1990s, then, Snake Eyes simply can’t be beaten. It’s just a shame that budgetary restraints prevented director De Palma from closing out the movie on his own apocalyptic terms. “I wanted to finish the movie with a tidal wave,” the filmmaker explains in the must-see documentary De Palma. “I thought that given the nature of Atlantic City and what goes on there, it might be interesting just to wipe the whole place off the map. So we shot that ending but then found that the effects budget wouldn't stretch to a tsunami. Because of that, we had to settle for the more conventional ending. Pity - I would've liked to see Atlantic City in ruins.”

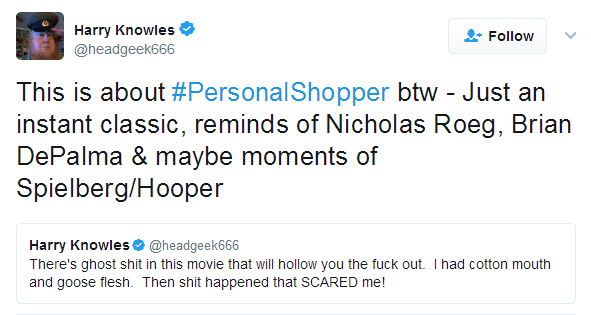

"What is a 'commercial film,' anyway? How do you know if a director makes a film because it is commercial, or because it corresponds to a personal desire? People often think that a personal film is not necessarily commercial, but it's not that simple. I would like to make a film that people really want to see. Fellini too, and it does not make him a 'commercial' director. - Brian De PalmaDr. Brian and Mr. De Palma explores the duality inherent in Brian De Palma's work in Phantom of the Paradise. Through an in-depth interview with him, analyses and press reviews, the iconoclastic approach of the director unfolds, between celebration and criticism of popular culture. An unpublished work embellished with the lyrics of all the songs of the film and 40 photos from the archives.

-PRESENTATION BY GERRIT GRAHAM

-PARADISE REGAINED (52 min)

-BRIAN DE PALMA IN THE COULISSES OF THE PARADISE (33 min) (a look back with De Palma)

-PAUL WILLIAMS INTERVIEWED BY GUILLERMO DEL TORO (72 mn)

-THE SWAN SONG FIASCO (11 min)

-CARTE BLANCHE WITH ROSANNA NORTON (10 min)

-PARADISE LOST AND FOUND (six cut or alternate scenes)

-KARAOKÉ 6 SONGS

-COMMERCIAL BY WILLIAM FINLEY

-RADIO SPOTS

-TRAILERS

As reported earlier, the cover art for the box was done by Matt Taylor.

I think if I had to choose, like, a fun guilty pleasure movie, I really like Brian De Palma’s Body Double. He’s kind of the king of guilty pleasures—he makes these beautiful movies that are really kind of cinematic objects, but that also have, like, a lot of sleaziness to them. Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t, but I kind of love them all.Brian De Palma made Body Double coming off of a lot of criticism of his previous film, Dressed To Kill. A lot of people said it was a little too gory, and that it focused a little too much on sex. But of course, being Brian De Palma, he just wanted to double-down on those criticisms.

It’s a big role for Melanie Griffith—I think a lot of people probably remember her character, Holly Body. And while this movie might seem a little trashy, she really credits it for doing a lot for her career. Specifically, she thinks she wouldn’t have gotten Working Girl or Something Wild without this movie kind of divorcing her from her childhood image as Tippi Hedren’s daughter.

My favorite sequence in it—and this is totally weird and out of place, but delightful—is in the middle of the film it breaks out into this Frankie Goes To Hollywood music video.

From the beginning (the end of the 60s) and until today (Passion, 2012), and tomorrow still certainly, the staging of Brian De Palma will never cease to play the game of cat and mouse. But in a version where the roles are constantly reversed: to be beaten at one's own game...Split screens, double focal lengths, slow motion, 360-degree panning, dives and counter-dives, multiplication of angles and axes, aerial camera, so many ways to expose a mise en scène or to sum up all reality to its mise en scène. In short, a sophisticated device of signs as so many indices that give the viewer the illusion of his omniscience: if all reality holds in its staging as in a box, then nothing is supposed to escape the one who Looks in the box. De Palma likes nothing more than to drive the spectator-voyeur, to make him go around the owner, to direct his glance and to designate a detail (to better conceal another). Is that not the very subject of Body Double?

The vertical plunge holds a place of choice in the De Palma fireworks. It is even a recurring motif of his work, a motif that is often quickly interpreted as a tribute to Hitchcock (the opening credits of North by Northwest, the staircase of Psycho, the tower of Vertigo, the pipe organ of Secret Agent…). In the visual economy of the cinema of De Palma, it is also the ultimate ruse: the zenithal point of view seems to make each spectator a god. Nothing escapes it apparently, everything is given to see and everything is seen, the foreground doubled as background. But this phantasm of all power makes him forget his constitutive infirmity: the spectator, like a character of De Palma, has no eyes in the back (if it were otherwise, Carlito would still be alive ...). It is there, at his back, that De Palma stands, and with him the truth of all his staging: there is always someone or something that looks at the one who looks. As in a game of mirrors, or in the painting by Magritte (Not to be Reproduced), one is always seen as "the eye was in the grave and looked at Cain" (Victor Hugo , La Conscience).

Well, it’s something I’ve been meaning to write for ages. I really planned to recharge my batteries and get back into writing. I’m excited about doing something that’s almost purely visual, because I’ve done three films—and even though Scott Pilgrim is very visual, it’s very dialogue heavy as well, which is great. And music heavy. Yeah. I think I’d like to try something—I’m a big Brian De Palma fan, and I’ll sit and look at something like "Carrie," and I like the fact that it starts to play out like a silent movie. There’s a point in "Carrie" in the last half hour where there’s no need for any more dialogue because the plot is in motion. Or something like [Jean-Pierre Melville's] "Le Samourai," I look at something like that and think, wow, there’s hardly any dialogue in this film. Something like that can be enjoyed around the world. I’d really like the challenge of doing something where the dialogue is really stripped back and it’s all about the cinema.

The Guardian's Anthony Quinn looks at Blow-Up 50 years on:

The Guardian's Anthony Quinn looks at Blow-Up 50 years on:And here is where the film unfolds its most brilliant and memorable sequence, the part you want to watch over and over again. Alone in his dark room, our hero blows up the photos from the park and discovers that he may have recorded something other than a tryst. Cutting between the photographer and his pictures, Antonioni nudges us ever closer until we see the blow-ups as arrangements of light and shadow, a pointillistic swarm of dots and blots that may reveal a gunman in the bushes, and a body lying on the ground. Has he accidentally photographed a murder?Contemporary audiences watching the way Thomas, the photographer, storyboards his grainy images into “evidence” would surely have been reminded of Zapruder’s film of the Kennedy assassination in 1963: the same patient build-up, the same slow-motion shock. When Thomas returns to the park he does indeed find a corpse. It’s the grassy knoll moment. We feel both his confusion and his excitement at turning detective – he’s involved in serious work at last instead of debauching his talent on advertising and fashion. But, abruptly, his investigative work goes up in smoke.

Next morning, the photographs and the body have disappeared. The woman has gone, too. This links to larger fears of conspiracy, a sense that shadowy organisations are hovering in the background, covering up their crimes – and getting away with it.

Blow-Up looks back to Zapruder but also ahead to Watergate and a run of films that riffed in a similar manner to Antonioni, with his inquiring, cold-eyed lens: Gene Hackman, stealing privacy for a living as the surveillance genius in The Conversation (1974); witness elimination and the training of assassins by a corporation in The Parallax View (1974); later still, Brian de Palma’s homage to the sequence via John Travolta’s sound engineer in the near-namesake Blow Out (1981). But these sinister implications are not on the director’s mind. Where we anticipate a murder mystery, Antonioni balks us by posing a philosophical conundrum. “It is not about man’s relationship with man,” he said in an interview at the time, “it is about man’s relationship with reality.”

Having created the suspense, he declines to see it through and sends Thomas off on an enigmatic nocturnal wander – to a party where he gets stoned, to a nightclub full of zombified youth where, bafflingly, he makes off with a broken guitar. (The film’s other symbolic artefact is an aeroplane propeller he buys in an antique shop). Finally, and famously, he encounters a bunch of mime-faced rag-week students acting “crazy” and playing a game of imaginary tennis on an empty court. We even hear the thock of the tennis ball, though there isn’t one in sight. Antonioni seems to offer only a shrug: reality, illusion, who can tell the difference? Whenever I watch Blow-Up, I feel a sense of anticlimax, of a road not just missed, but refused. Yet as much as it irritates, it still intrigues, and asks a question that relates not merely to cinema but to any work of art: can we enjoy something even if we don’t “get” it?

Conrad Brunstrom, literary scholar and blogger, posted today about Dionysus In '69:

Conrad Brunstrom, literary scholar and blogger, posted today about Dionysus In '69:Many years ago, I read a book by Bill Shepherd about the experience of preparing for and performing Dionysus in 69. Shepherd describes the process of rehearsing for Dionysus as something akin to cult membership – [an] exhausting and all demanding process that lasted many months. This kind of “living theatre” has a tendency to treat the performance as a mere symptom of a process rather than as the defining end product.I recall that Shepherd describes how Richard Schechner created and sustained The Performance Group in that garage that wasn’t really a garage. At one point, he reported to the cast that Jerzy Grotowski (no less) had seen an early production and complained that the partial nudity looked a bit tacky. On Grotowski’s second-hand authority therefore, Schechner persuades the cast to get the rest of their kit off.

The name Dionysus in 69 does a number of things in the context of a 1968 production. 69 is a rude number – which helps. It’s also “next year” – an imminent revolution. And of course, there is the important context of the 1968 US election, in which the Vietnam War is a decisive issue. [Finley]-Dionysos is the candidate to become President in 69.

The casual use of “real” names alongside Euripidean roles has a genuinely unsettling effect in the production. The audience wonders whether they are watching a staged or a real argument, a play or a group therapy session.

Does it all work? Is the blood and the nudity and the dicing with mental health all justified in the name of art? Well…. yeah… I think so. I was worried that the production would seem desperately ponderous and self important. In fact, the wit of the production is what shines through. Euripides is a disturbingly funny playwright, and enough of the Arrowsmith translation is integrated into this theatre work to demonstrate the joyous absurdity of religious conflict. And William [Finley] is a remarkable Dionysos – calm, comical, terrifying and seductive. The scene where he demands oral sex from Pentheus and/or Bill Shepherd is as careful and exquisitely delivered as anything I’ve ever seen on stage or in a film, or in a film that’s also a stage or a stage that’s also a film. Yes, it’s heavy on sex and death and liturgy – but there is a constant playfulness on show here as well. It’s consistently entertaining.

Brian De Palma uses a split screen technique to show the audience and the cast simultaneously. It’s a technique he would use in more famous films like Carrie and Dressed to Kill. On the one hand, this reminds us that everything we see is designed for a live audience. On the other hand, this “division” of the screen is precisely the division that is continually being violated by the Performance Group. It is increasingly impossible to separate cast from audience – and not just when they’re all groping one another. Apparently, this film joins together two separate productions. I for one, cannot see the join.

The one barrier that can’t be transcended of course is the essential “pastness” of film itself. The cast transgress every conceivable barrier between actors and audience, between cast names and “real names” and finally, with the triumphant bursting forth into the streets – between theatrical reality and the so-called “outside world”. The final gimmick that De Palma might have added might be a smashing through a cinema screen to terrify a theatre full of complacent movie goers. And then we’d be able to extrapolate and imagine Dionysos and company bursting out of our smaller screens to invade our dull and safe little worlds.