"UNPACKING THE CINEMATIC STYLE & THEMATIC PREOCCUPATIONS OF PAUL SCHRADER, IN THE DIRECTOR'S OWN WORDS"

Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | July 2024 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 |

| 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | |||

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

Pictured at left, from 2007, is Alejandro González Iñárritu, handing Brian De Palma the Silver Lion for Best Director for Redacted at that year's Venice Film Festival. Iñárritu was a member of that year's jury, which awarded the prize to De Palma. Also on the jury that year: Zhang Yimou (jury President), Ferzan Ozpetek, Paul Verhoeven, Emanuele Crialese, Catherine Breillat, and Jane Campion. Speaking at the podium after receiving the award from Iñárritu, De Palma told the audience, "Prizes are always great because it helps your film to be seen. But critics and prizes just tell you what the fashion of the day is. We don't make movies to get prizes."

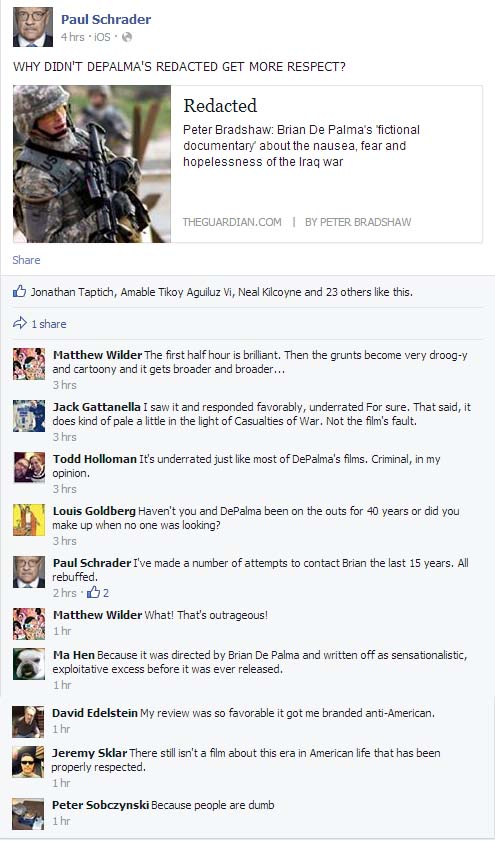

Pictured at left, from 2007, is Alejandro González Iñárritu, handing Brian De Palma the Silver Lion for Best Director for Redacted at that year's Venice Film Festival. Iñárritu was a member of that year's jury, which awarded the prize to De Palma. Also on the jury that year: Zhang Yimou (jury President), Ferzan Ozpetek, Paul Verhoeven, Emanuele Crialese, Catherine Breillat, and Jane Campion. Speaking at the podium after receiving the award from Iñárritu, De Palma told the audience, "Prizes are always great because it helps your film to be seen. But critics and prizes just tell you what the fashion of the day is. We don't make movies to get prizes."Schrader's comments spread through Twitter Friday, leading him to delete the entire post, but the comments continued to spread over the weekend. Sometime soon, I will post a brief timeline, with quotes, between De Palma and Schrader. For now, here's an image of Schrader's FB post from March of 2015:

At The New York Film Critics Circle’s annual awards dinner Monday, Martin Scorsese presented the Best Screenplay award to Paul Schrader for First Reformed (image here cropped from a tweet by Alissa Wilkinson). In his ten-minute intro for the award, Scorsese mentioned meeting Schrader via Brian De Palma, saying that the three of them would go to screenings of Yasujirō Ozu films together. According to IndieWire's Zack Sharf, Scorsese added that Schrader's license plate back then read O-Z-U. "After discussing how their shared love of John Ford’s The Searchers and Robert Bresson’s Diary of a Country Priest made them fast friends," writes Sharf, "Scorsese championed First Reformed: 'I was so impressed and moved by the way Paul discusses the nature of faith and how it’s bolstered by Ethan Hawke, who gives such a magnificent performance and goes so deep into his character’s pain, into his long, twisted road to understanding.'”

At The New York Film Critics Circle’s annual awards dinner Monday, Martin Scorsese presented the Best Screenplay award to Paul Schrader for First Reformed (image here cropped from a tweet by Alissa Wilkinson). In his ten-minute intro for the award, Scorsese mentioned meeting Schrader via Brian De Palma, saying that the three of them would go to screenings of Yasujirō Ozu films together. According to IndieWire's Zack Sharf, Scorsese added that Schrader's license plate back then read O-Z-U. "After discussing how their shared love of John Ford’s The Searchers and Robert Bresson’s Diary of a Country Priest made them fast friends," writes Sharf, "Scorsese championed First Reformed: 'I was so impressed and moved by the way Paul discusses the nature of faith and how it’s bolstered by Ethan Hawke, who gives such a magnificent performance and goes so deep into his character’s pain, into his long, twisted road to understanding.'”“My mother gave birth to me when she was 18 and one of the things she hid from her father was her subscription to The New Yorker magazine,” Hawke said. “It’s a weird thing to combine white trash and The New Yorker, but that’s my family. When I was growing up, what she used to do was save The New Yorker and whatever Pauline Kael reviewed was the movie we would go see. After we saw it, we would read Pauline Kael’s review, which we often did disagree with. … Even after ‘Dead Poets Society’ came out I had to go home and sit at the dinner table and read Pauline Kael’s very negative review of that movie. ‘The whole thing is wrapped in a gold bow like a bunch of bullshit. If I have to see another movie that makes me glad I’m alive I’ll have to kill myself,” is what I think she said.”Hawke’s ability to pivot from humorous anecdote to profound meditation remains unmatched. “In my life, I have witnessed big business absolutely devour an extremely young art form,” he said at the end of his speech. “We live in a culture that hero worships the accumulation of wealth and then acts surprised about who we elect as our officials. Film criticism establishes a different barometer of success and it teaches audiences what to look for, how to watch movies, how to listen to stories, and I’m so grateful to articulate why all these movies you are celebrating tonight matter, because they matter to me.”

See Also:

Mark Jacobson, Vulture

In Conversation: Paul Schrader

First Reformed's intellectualized, detached, and emotionally reticent notion of suicide recalls Bresson's The Devil, Probably. Bresson, along with Ozu and Dreyer, formed a trinity at the heart of Schrader's book Transcendental Style in Film, and the filmmaker has faithfully returned to them again and again, channeling them in most of his directorial efforts, working within the so-called “Tarkovsky Ring” (films made within this ring will find commercial distribution, films like those of Bresson and Roberto Rossellini, while films outside of this ring are destined for museum and festival existences). Schrader was raised in an austerely Calvinist home, but at the age of 17 he converted to cinema. First Reformed is about Schrader's film theories, about the transcendent possibilities of the medium, as much as it is about religion.The film is, even by Schrader's standards, a bleak endeavor, concerned with the durability of spirituality, its susceptibility to corruption and radicalism, and its place in modern American life: with the slow decay of the planet, as well as with pain, penance, and the validity of suicide and murder. Invidious, at times startlingly beautiful, and at others startlingly ugly, it encapsulates Schrader's cinematic philosophies, the testament of a man who worships film. It's a churlish and controlled film, suffused with dolor yet agleam with the prospect of hope, each assiduous and apoplectic composition as neat and orderly as the garments Toller adjusts during his morning routine.

Shot by Alexander Dynan, First Reformed has a mostly familiar, competent aesthetic, with subjects and their surroundings structured in a geometric style reminiscent, again, of Ozu. The repetition of shots—what film theorist David Bordwell refers to as “planimetric shots,” faces isolated in the frame, buildings filmed head-on, the camera unmoving and observant—insinuate a life of tedium, devoid of variety. There's little ambiguity in the deep focus. The camera isn't liberated. But as Toller's faith grows increasingly strained, his revelations more and more exceptional, the shots go aslant, the camera moving more. The final shot, twirling oneirically, the camera jubilant as it circles around Toller and Mary in bloody embracement, feels torn from a Brian De Palma film, out of place with the phlegmatic style of Schrader's. It suggests a dream, an Empyrean awakening. It brings to mind a bible quote, from Revelation 17:6: “And I saw the woman, drunk with the blood of the saints, the blood of the martyrs of Jesus. When I saw her, I marveled greatly.”

First Reformed feels like a culmination of and response to Schrader's career. It harks back to Martin Scorsese's New York nightmare Taxi Driver by using a journal as a narrative device. Both films use a laconic, unexpurgated voiceover to elucidate on the inner turmoil of a man whose well-being is eroding and whose disdain for the people around him grows with each passing day and toward a violent epiphany. Schrader has said that he knows his obituaries will read, “Writer of Taxi Driver,” despite his own idiosyncratic career as a filmmaker. With First Reformed, he seems to be rewriting his own legacy, revisiting the infatuations and compulsions that inspired the Scorsese film.

Travis Bickle wants to wash from the streets the decay he perceives in modern life. He's a man who anoints himself an angel of death, come to smite New York City's miscreants. The backseat of his cab is, at the end of each night, doused in blood and cum, the way the faithful are awash in the blood of the lamb. In Travis one finds the seeds of Schrader's obsessions: penitence, sin, tortured veterans, working-class malaise, men with complicated relationships with sex. Like Travis, Toller sees grotesqueries and unforgivable misdeeds, and his notion of atonement becomes more extreme. He turns away the longing of his ex-wife, Esther (Victoria Hill), who leads the megachurch's choir and secretly pines, in pain, for Mary. His faith, while tested, never corrodes; it becomes more steadfast, more Old Testament-like. Misery begets penance, suffering ameliorating the sins of humanity. Toller rejoices in his suffering, and through him Schrader has found his faith in cinema renewed.

For the role of the conflicted clergyman, Schrader said Ethan Hawke was an easy choice.“There’s a certain physiognomy in playing a man of the cloth, be it Montgomery Clift in ‘I Confess,’ Belmondo in ‘Leon Morin’ or Claude Laydu in ‘Diary of a Country Priest.’ So, you’re thinking about actors who have that physiognomy, maybe Jake Gyllenhaal, Oscar Isaac, but Ethan was 10 years older than them and his face was getting some very interesting wrinkles. I started thinking he’s just right for this. I sent him the script and he responded right away.”

Hawke’s performance goes from contemplative to harrowing as he considers ecoterrorism.

“He’s going to blow up a church, but this pregnant woman arrives and he can’t do it, so he reverts to turning himself into the sacrifice. This is a pathological fallacy deeply embedded in Christianity, the notion of suicidal glory, that my own suffering can redeem me. It’s not what the Bible teaches, (nor) what Jesus taught. It is a fallacy that is virtually the same as Jihadism.”

Hawke’s self-purgation finds him drinking Drano and wrapping himself in barbed wire.

“It’s a reference to Flannery O’Connor’s ‘Wise Blood’ (by) John Huston, where Hazel Motes at the end of that book puts his eyes out, wraps him up with wire and goes out preaching.”

This sacrifice is ultimately alleviated when Seyfried enters the room and the two embrace amid a swirling camera. It’s the first time the camera moves. Schrader uses a static camera with a 4:3 aspect ratio for the entire movie, before unleashing a circling camera like Alfred Hitchcock’s “Vertigo” (1958) or Brian De Palma’s “Obsession” (1976), which Schrader wrote.

“When you start working on the spiritual side of the street, the still side of the street, you have to stretch time,” Schrader said. “This is a very static film. The camera does not move, pan or tilt. It just sits there. It is very passive aggressive and takes too long to do everything. All of a sudden at the end, it jumps like a bird from a cage into a kinetic, whirly-gate soul in flight.”

As the camera circles, the soundtrack delivers the spiritual hymn “Leaning on the Everlasting Arms.” Film buffs will recall Charles Laughton’s “The Night of the Hunter” (1955), though Schrader insists it’s a reference to singer George Beverly Shea of the Billy Graham Crusade.

“That song, my father would play over and over again,” Schrader said. “(The final scene) is meant to be read in different ways. If you want to say he’s dead and imagining this, I wouldn’t object. If you want to say it’s a miracle, I wouldn’t object. If you want to say it is a redemption, I wouldn’t object. In fact, I don’t know the answer. It’s all of those things put together.”

This isn’t Schrader’s first ambiguous, dreamlike ending. A similar fate befell Travis Bickle (Robert DeNiro) in Martin Scorsese’s “Taxi Driver” (1976), who similarly attempted an act of terror before embracing his better angels. In that case, it was a political assassination before shifting to vigilante justice by killing the pimp (Harvey Keitel) of a teen prostitute (Jodie Foster).

Kotto at Eat The Blinds has posted a photo essay about Paul Schrader's American Gigolo, which might be thought of as sort of an older sister to Brian De Palma's Scarface. Kotto states, "Both the opening shot and the soundtrack blaring Blondie's Call Me welcome viewers not only to the movie, but more importantly to the 1980's. The music, the clothes, the vapidity and the vanity...this is what defined the 80's and this is Paul Schrader's American Gigolo." Kotto concludes his essay with the following:

Kotto at Eat The Blinds has posted a photo essay about Paul Schrader's American Gigolo, which might be thought of as sort of an older sister to Brian De Palma's Scarface. Kotto states, "Both the opening shot and the soundtrack blaring Blondie's Call Me welcome viewers not only to the movie, but more importantly to the 1980's. The music, the clothes, the vapidity and the vanity...this is what defined the 80's and this is Paul Schrader's American Gigolo." Kotto concludes his essay with the following: As far as thrillers go, AG is perhaps a little on the un-engaging side. While it does share many stylistic similarities to the work of Brian De Palma, Schrader proves to be less concerned with technique and aesthetics and much more fascinated by the underlying psychology of his characters. While De Palma's films tend to be over-the-top, AG is anything but the opposite; this may interest some, but it will surely bore others. One thing remains certain: few films established the 80's in the same way.

Newer | Latest | Older