JENNIFER SALT AS REPORTER GRACE COLLIER

Updated: Thursday, May 2, 2024 11:47 PM CDT

Post Comment | Permalink | Share This Post

Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | July 2024 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 |

| 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | |||

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

The first couch potato was named and affectionately shamed in Pasadena, California, in 1976, when Tom Iacino, an illustrator and designer, made a phone call to his TV loving friend Robert Armstrong, a cartoonist. According to an interview Iacino gave to Bon Appétit in 2014, Armstrong’s girlfriend picked up, and Iacino asked, “Hey, is the couch potato there?”. When she looked over and actually found him on the couch, she cracked up. Armstrong soon asked his friend to trademark that unplanned, brilliant coinage, and in 1979 they took part in an alternative parade, the Doo Dah Parade, with a floating showing a floor with a couple of couches on it. In 1983, Armstrong and the writer Jack Mingo published “The Official Couch Potato Handbook,” a sort of ironic hymn to slouching proudly in front of the TV, taking a stand against Californian healthy lifestyle in the 70s. Armstrong even created a newsletter called The Tuber's Voice that went into many editions.

According to the catalog of the American Film Institute, Sisters carries a copyright date of April 18, 1973. This is when it landed in theaters in Los Angeles, although, moving throughout the U.S., it would not reach New York theaters until October of 1973. That month, De Palma was interviewed by The New York Times' Charles Higham:

De Palma gets up, coldly answers a persistent telephone caller, and then sinks back in his chair, looking tired and puffy. “I'm much happier with ‘Sisters.’ That is mine from beginning to end. American International took on the distribution — but they didn't tamper with it at all. It was shot on location on Staten Island, I liked the idea of a very suburban setting for a horror story about a small‐town girl reporter who sees a murder from her apartment window.”Not all of “Sisters” was shot on Staten Island, however. “We built the set of the apartment where the murder takes place on East 4th Street, right next to the Cafe La Mama. I loved the voyeuristic mood of the story —here is this girl, this amateur sleuth, who gazes through windows and sees a man murdered and all kinds of horrifying things going on. Things half‐seen. Like most directors, I'm a voyeur at heart. I loved dragging the audience through the whole psychodrama of an insane situation. The audience becomes this girl, peering through a psychological hole. Since, in a way, I am the girl, the people out there can be her, too.”

Previously:

Posted April 13 2004

TARANTINO TALKS KILL BILL

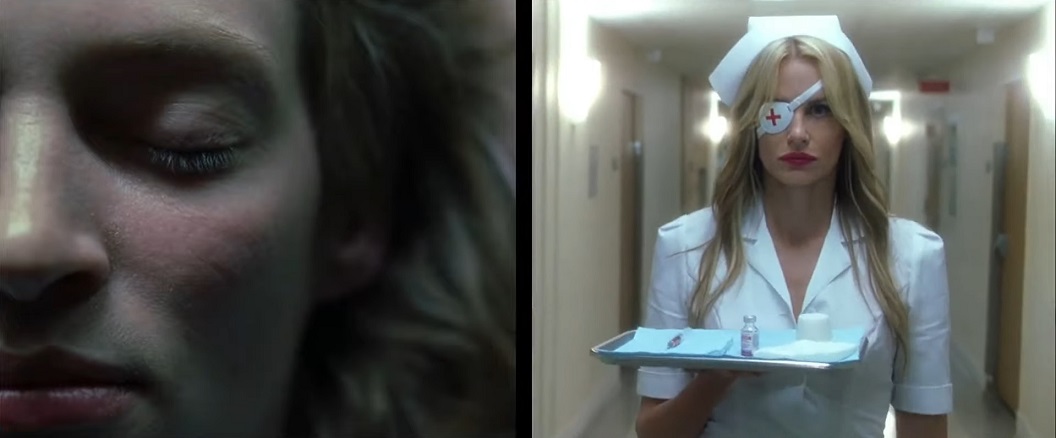

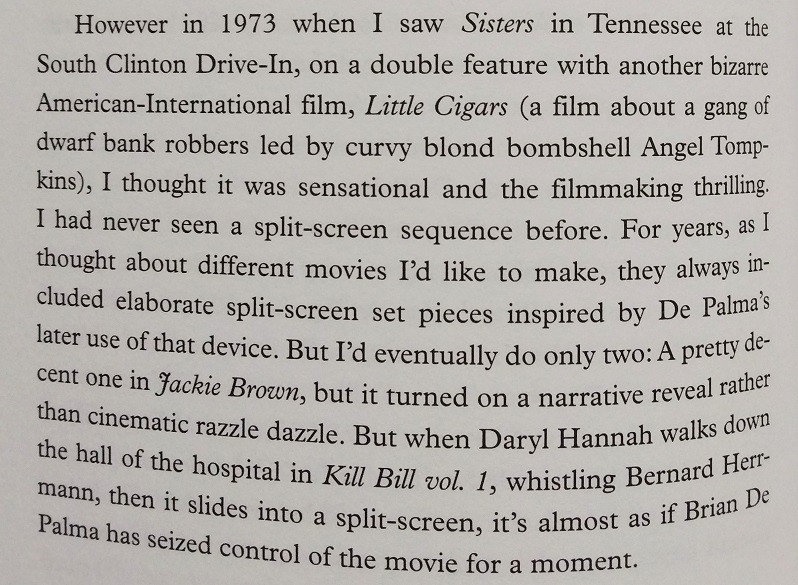

EXPLAINS HIS "LITTLE BRIAN DE PALMA SCENE" It seemed logical that the split-screen sequence in Quentin Tarantino's Kill Bill Vol. 1, where Daryl Hannah dons a nurse's uniform and whistles a Bernard Herrmann melody while carrying a deadly syringe down a hospital corridor, was inspired in great part by a combination of Brian De Palma's Sisters and Dressed To Kill. On the new DVD release of the film, Tarantino even calls it his "little Brian De Palma scene." But the filmmaker tells Premiere that this particular split-screen sequence was inspired by the trailer for a John Frankenheimer film-- a scene in the trailer that was cut and scored differently than it was in Frankenheimer's film. Tarantino explains that he does not duplicate other directors' shots when he references their films in his work, but rather "a feeling in the shot or an aspect about the shot I liked." He then explains how he has a collection of 35mm trailers from movies, particularly from the '70s, and how these trailers are works of art in and of themselves in that they used techniques that Tarantino likens to the work of Godard. Having seen the films that these trailers promote, Tarantino claims that many of the scenes or sequences shown in the trailers are not in the actual films. "It's just in the trailer," he tells Premiere:

It seemed logical that the split-screen sequence in Quentin Tarantino's Kill Bill Vol. 1, where Daryl Hannah dons a nurse's uniform and whistles a Bernard Herrmann melody while carrying a deadly syringe down a hospital corridor, was inspired in great part by a combination of Brian De Palma's Sisters and Dressed To Kill. On the new DVD release of the film, Tarantino even calls it his "little Brian De Palma scene." But the filmmaker tells Premiere that this particular split-screen sequence was inspired by the trailer for a John Frankenheimer film-- a scene in the trailer that was cut and scored differently than it was in Frankenheimer's film. Tarantino explains that he does not duplicate other directors' shots when he references their films in his work, but rather "a feeling in the shot or an aspect about the shot I liked." He then explains how he has a collection of 35mm trailers from movies, particularly from the '70s, and how these trailers are works of art in and of themselves in that they used techniques that Tarantino likens to the work of Godard. Having seen the films that these trailers promote, Tarantino claims that many of the scenes or sequences shown in the trailers are not in the actual films. "It's just in the trailer," he tells Premiere:

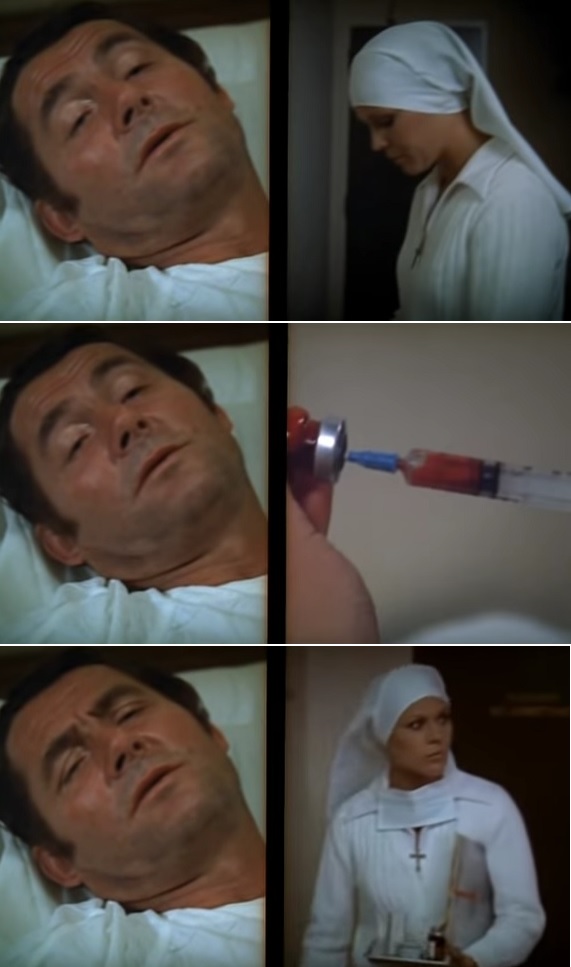

There's this one trailer for Black Sunday by John Frankenheimer that has a scene in it that's done differently than it is in the movie. It's amazing. There's a scene in the movie-- it's like, you know, killer terrorist shit-- where Marthe Keller is going to kill Robert Shaw, who works for the Israeli Army. He's in the hospital, so she dresses up like a nurse with a syringe full of lethal injection, and she's going to go into his hospital room and inject him. Well, in the movie it's an okay sequence, but not really that special. They don't really milk it that much. It's routine.

But in the trailer for the movie, when it gets to showing us that sequence, they do the whole thing in split screen. And where they just had natural sounds playing in the movie, they have John Williams's Black Sunday theme [humming the tune] pulsing through the whole trailer, so it's just ticking beats to the images. This is not in the movie anywhere. This is one of the best split-screen sequences I've ever seen.

So for Kill Bill, I say, "We're doing this when Elle Driver shows up at the hospital."

And then I have another, like, weird movie reference in there because I have Daryl Hannah whistling-- she learned how to whistle Bernard Herrmann's theme to this movie called Twisted Nerve. And the thing is, when she leaves the frame, the Bernard Herrmann score kicks in, you hear the same theme done in this lush Bernard Herrmann melody, and then it goes into split screen and it looks like I'm doing an homage to Dressed To Kill-era De Palma.

Bernard Herrmann scored two De Palma films: Sisters (1973) and Obsession (1976). Daryl Hannah made her film debut in De Palma's The Fury (1978), which was scored by John Williams. One character, Bobbi, steals a nurse's uniform to wear in De Palma's Dressed To Kill (1980). Sisters and Dressed To Kill each feature memorable split-screen sequences.

Newer | Latest | Older