Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | July 2024 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 |

| 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | |||

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

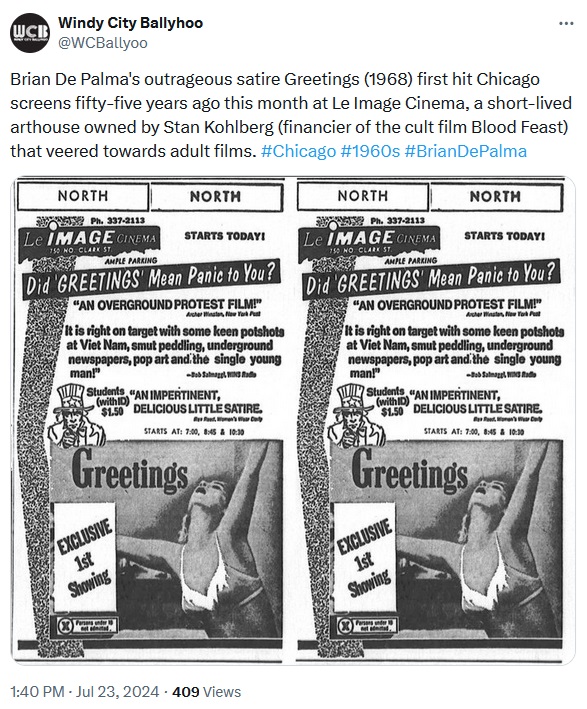

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

The 4K UHD Blu-ray + Blu-ray + Digital SteelBook Combo Pack will include a Dolby Vision presentation and Dolby Atmos audio with the following specs and supplements:

4K ULTRA HD DISC

- Feature presented in 4K resolution with Dolby Vision

- English Dolby Atmos + English 5.1 + English 2-Channel Surround

BLU-RAY DISC™

- Feature presented in high definition, sourced from the 4K master

- English 5.1 + English 2-Channel Surround

- Special Features:

- NEWLY ADDED: Archival EPK Interviews with Brian De Palma, Craig Wasson and Melanie Griffith

- NEWLY ADDED: Frankie Goes to Hollywood "Relax" Music Video (BODY DOUBLE Version)

- 4 Featurettes:

- The Seduction

- The Setup

- The Mystery

- The Controversy

- Still Gallery

- Theatrical Trailer

CAST AND CREW

- Produced and Directed By: Brian De Palma

- Story By: Brian De Palma

- Screenplay By: Robert J. Avrech and Brian De Palma

- Cast: Craig Wasson, Gregg Henry, Melanie Griffith

SPECS

- Run Time: Approx. 114 minutes

- Rating: R

- 4K UHD Feature Picture: 2160p Ultra High Definition, 1.85:1

- 4K UHD Feature Audio: English Dolby Atmos (Dolby TrueHD 7.1 Compatible) | English 5.1 DTS-HD MA | English 2-Channel Surround DTS-HD MA

Much of The Substance is framed in close-ups with wide-angle lenses, with sets bathed in lurid colors. Fargeat pays homage to a bathroom from Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining, and the general vibe of her film suggests a meeting of Dr. Strangelove’s humor and the New French Extremity movement’s brutality. It’s an ultraviolent hothouse cartoon of avarice. Kubrick aged into a scold, but Fargeat can admit that the decadence she’s parodying and indulging turns her on. This is a feminist midnight-movie freak show, and Fargeat is willing to beat horny male filmmakers at their own game while spanking them for their misconduct. As she also illustrated in the equally unhinged Revenge, the thin line between critique and hypocrisy is her natural habitat.The Substance rarely steps outside or ventures beyond three characters: Elizabeth, Harvey, and Sue (Margaret Qualley), a young upstart rival of an unusual nature. Borrowing a subtle device from David Cronenberg’s The Fly, Fargeat compresses a potentially epic premise down to a few locations and variables. Most of the narrative is set in Elizabeth’s apartment, the soundstage for the fitness show, and a few warehouses and studios. The film is insular and claustrophobic, placing us almost subliminally on Elizabeth’s harried wavelength.

Among the stylization and cheeky editorial dialogue, Moore’s naturalistic performance serves as a powerful counterpoint. There was a steely earnestness to her work in her ingenue days, an eagerness to prove herself that was appealing but tended to freeze her up. In The Substance, that steel is contextualized as a fading defense device. Moore achieves a casualness of being that often happens to beautiful stars who survive the game long enough to absorb said survival into their essence. The stakes are upped by the fact that Elizabeth is unavoidably a riff on Moore herself, who’s played her own version of the Hollywood commodification game.

Moore’s payday for going topless in Striptease in the 1990s was treated as a shot heard around the world by the press, and the film itself was revealed to be an embarrassingly self-conscious non-event. Moore is also frequently nude in The Substance, but the context is markedly different. We often see Elizabeth naked either in her large bathroom or in a chamber behind the bathroom that’s seen as a kind of cocoon. This is a place without endlessly scrutinizing eyes, one of refuge, and Fargeat films Moore tenderly. In these sequences, The Substance lets up on the flashy aesthetic and gross-out jokes, and Elizabeth is allowed to simply be a person, contemplating with considerable pain an inevitable shift into older age.

The humanity of Moore’s performance, the greatest of her career, gives Fargeat’s boldest ideas an emotional backbeat. This is a blend of body horror film and feminist satire that’s more than a tribute reel to the usual masters of the genre. When Elizabeth’s back splits open on the bathroom floor and Sue arises fully formed out of a viscous placental sac, we’re processing more than uniquely inventive special effects. We’re seeing a woman voluntarily efface herself, tagging in a newer model who can satisfy the carnal appetites of the Harveys of the world.

Via a kind of deus ex machina, Elizabeth learns of a black-market procedure that promises the regeneration of her cells, allowing her to be a better version of herself. The details of The Substance—how it’s obtained, injected, and maintained—are among Fargeat’s sharpest satirical flourishes. Think Lewis Carroll’s wild irrationality united with Philip K. Dick’s distrust of corporations as a parody of the self-improving snake oil that’s sold to people, with sexy and fashionably minimalist ad campaigns that are meant to suggest confidence and legitimacy.

Sue is supposed to be this better version of Elizabeth, though the faceless mastermind of The Substance has to remind them both that they’re one in the same woman, and that they need to work together. Elizabeth must regenerate while Sue is out in the world and vice versa, and they must switch places every seven days. Inevitably, this balance is ruptured, and a fight for dominance commences as Sue grows in power and prominence.

Fargeat films Qualley differently than Moore, as Sue reflects the populace’s fantasies of luscious rising celebrities as well as Elizabeth’s self-loathing. Qualley is lit and made up here to suggest the faint anonymity of Hollywood sexiness: Her face is softened and colored like cotton candy, her lips are accentuated, and she’s often in pink undies and butt-hugging workout gear.

Fargeat drinks in Qualley so rabidly that even Michael Bay might be driven to blush, staging objectifying scenes that are hot and funny and resonant. Qualley’s airbrushed-feeling sexiness here may startle people who are familiar with her eccentric and highly personable previous performances, and a portion of that audience may have to confront the fact that they like this sexbot version of Qualley despite their better instincts.

When Sue cracks open a Diet Coke, the glistening soda complimenting her moist lips, the charge of the image springs from the fact that the satire of commercial objectification can’t dispel the disreputable eroticism of the moment. When Sue takes over Elizabeth’s show, Fargeat springs an even wilder set piece, a workout number so robotically sexual that it suggests a Jazzercise session restaged as a lap dance from Paul Verhoeven’s Showgirls. Fargeat’s premise allows her to mount a free-associational essay on men’s hunger for women as well as women’s simultaneous craving of that attention and resentment of it. That idea also drove Showgirls and its precedent, All About Eve, and as long as The Substance is mining this turf, it’s exhilarating.

The Substance is also an unwieldy movie-movie that desperately needs to come up for air at some point. To borrow a Cronenbergian metaphor, things keep growing out of this film, and Fargeat’s cinema fever is sometimes at odds with her powerful take on two women, sisters of sorts, who feel as if they need to destroy each other in order to matter.

In that vein, it makes sense to lean on Showgirls and Brian de Palma’s Carrie and Brian Yuzna’s Society and even Cronenberg’s The Fly, but the late-inning embrace of the imagery of Darren Aronofsky’s Requiem for a Dream feels slapdash, momentarily knocking The Substance off its axis. But it’s impossible to deny that Fargeat’s film holds you even at its most frenzied, and it ends on an unforgettable image that circles back to the first, in which Elizabeth’s monstrous self-loathing is granted the reprieve of her biggest fear: obscurity.

Perkins’ film is full of left-field surprises, made more unexpected by its blend of genres. Set in the morally dicey 1990s, it’s a bit rural police procedural, a la “Twin Peaks,” but its supernatural and religious elements add shades of Brian De Palma’s “Carrie.” As does Perkins’ artful shots.Fear lurks under every ideally lit archway. And each detailed, stale room has the same foreboding of exploring your grandparents’ dusty old basement as a child.

And as Lee investigates these sinister places, [Maika] Monroe is excellent. Her Lee is troubled and off-putting, yet unsuspectingly funny, too. Phone calls with Lee’s slightly off mother Ruth (Alicia Witt) are layered. They don’t seem to like each other much, but she calls mom daily all the same.

Monroe has had an up-and-down career. I especially enjoyed her in 2019’s “Honey Boy,” although there have been quite a few more “Bling Ring”s on the resume. This focused and serious performance will mark a turning point in the actress’ career.

[Nicolas] Cage’s left turn into Crazytown happened a long time ago, and I’m loving the warped ride.

What’s so unsettling about his Longlegs is, as big and cartoonish as he is, the weirdo is just believable enough. You could run into him late at night at a highway rest stop or, God forbid, on an empty subway platform. Cage makes a meal out of the murderer.

During this so-so summer at the movies, something’s finally got legs.

Meanwhile, at Fangoria, Phil Noble Jr. writes:

Until I get off my ass and start a podcast of my own, I’m happy any time I’m invited onto someone else’s. Being invited onto someone else’s podcast to talk Phantom of the Paradise? I’ll do that all day. It’s one of my favorite, most formative movies, and my love for it has, over the years, given back to me more than I can measure.So I was very happy indeed to join Chris Slusarenko’s Revolutions Per Movie podcast (along with with visual artist and musician Perry Shall) to geek out for an hour and change over Brian De Palma’s 1974 film, which has in my lifetime gone from box office dud to secret handshake to out-of-print cult favorite to beloved classic of the canon.

Chris and Perry share my love for the film, so if you wanna hear people argue, this isn’t for you. But if you wanna hear three dudes unabashedly love on a once-forgotten glam rock musical horror epic, head here (or wherever you get your podcasts) to get an earful of it!

If there’s an animating force behind Blow Out, it’s De Palma’s love of filmmaking. His fondness for split diopter shots—when two objects at disparate distances are seen in focus at once—serves him well here, making the viewer’s eyes dart back and forth to grasp the juxtaposition, replicating the inner workings of Jack’s mind. De Palma’s use of pink and red lighting lends the proceedings a lurid overtone, while the pounding score by Pino Donaggio accentuates the filmmaker’s maximalist style.More importantly, De Palma is mostly here to watch Jack piece together the mystery by using the building blocks of filmmaking. The newspaper obtains video of the accident, and Jack cuts out the photos, putting together a crude flipbook. It’s almost as if he is creating cinema all over again. De Palma lingers on these scenes, his camera seduced by Travolta’s dexterous fingers and his famously determined chin. This sequence—and the film as a whole—is a loose remake of Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1966 classic Blow-Up about a fashion photographer who scrutinizes his own photographs to solve the mystery of a missing woman. But De Palma is more upfront about his voyeuristic tendencies. We can feel his yearning in the painstaking detail with which he shoots these scenes, but his passion extends beyond mere affection. The scenes of Travolta mastering the editing equipment, splicing together sound and film, are as sensual as any of the director’s famous sex scenes.

Blow Out is a strange, perverse film, and unsurprisingly, it wasn’t a hit when it was released in 1981. Made for $18 million (a lot at the time), Blow Out flopped upon its initial release and was only reclaimed by the next generation of cinephiles. Quentin Tarantino praises it to the heavens, and it’s easy to see how De Palma’s brash, lurid style was a clear influence on the young director, who, somewhat less elegantly, also challenges viewers with their voyeurism and implicates them in his on-screen violence. In that way, Blow Out does have something to say about the country that produced it, a place where we consistently pretend to care about the victims but we really can’t tear our eyes away from the screen.

Happy Fourth of July, everyone.

Newer | Latest | Older