AS STEPHEN KING'S FIRST NOVEL TURNS 50 TODAY - NY TIMES ESSAY BY AMANDA JYATISSA

Stephen King's debut novel, Carrie, was released 50 years ago today, April 5. In an article linked to this anniversary, Betty Buckley talks a bit about the making of the 1976 Brian De Palma film to People Magazine's Eric Anderson:

In the book, the gym teacher was named Rita Desjardin, but called Miss Collins in the movie. Future Broadway and Eight Is Enough star Betty Buckley played Miss Collins on screen. She also petitioned director Brian De Palma to let her character live!“I kept saying to him, ‘She shouldn't die. She didn't die in the book,’” Buckley, 76, tells PEOPLE. “And I'm like, ‘Seriously, Brian, don't kill Miss Collins off. Let her go to the end.’”

Unlike in the novel, which saw the gym teacher survive, Miss Collins becomes one of Carrie’s victims at the prom after Carrie is doused in a bucket of pig’s blood in a humiliating prank pulled by her chief tormenter Chris (Nancy Allen).

Furious and embarrassed, Carrie locks the doors of the school, trapping everyone inside while an electrical fire breaks out.

As chaos ensues, Miss Collins is crushed to death by a falling basketball backboard. “That was my first death scene. It was pretty classic,” says Buckley, who felt uneasy about filming it after seeing a stunt coordinator working on the movie get seriously injured.

The coordinator was doing another scene in which he was thrown in the air as one of Carrie's classmates who gets killed. “There was a mattress for him to land on, and they miscalculated the distance and he hit the ground and hurt himself badly,” recalls Buckley.

“So we all witnessed that and we’re like, ‘What? Are we in safe hands?” adds Buckley, who became nervous that she’d be injured, too.

Buckley’s character is pinned against a wall when the basketball backboard falls. The pendulum-like apparatus was on ropes, and Buckley says there was a piece of balsa wood that was supposed to prevent any injury to her: “That was the safety mechanism.”

“Oh, this'll work,” Buckley says she was told, but she was not entirely sure: “The terror you see from Miss Collins when that happened was absolutely real.”

Despite that, Buckley, who starred alongside Spacek, Allen, John Travolta, Amy Irving and William Katt in the film, loved making Carrie.

“We all had so much fun, and there were seven of us making our film debut, including John Travolta,” she says. “And the group of us were just so excited to be doing it. Sissy Spacek had done some films, and so she was a veteran, all chill and everything. And the rest of us were like, ‘Oh, Hollywood, we're so excited to be here!’”

Meanwhile, at the New York Times today, novelist Amanda Jayatissa has written a guest essay with the headline, "The Rage in Carrie Feels More Relevant Than Ever" -

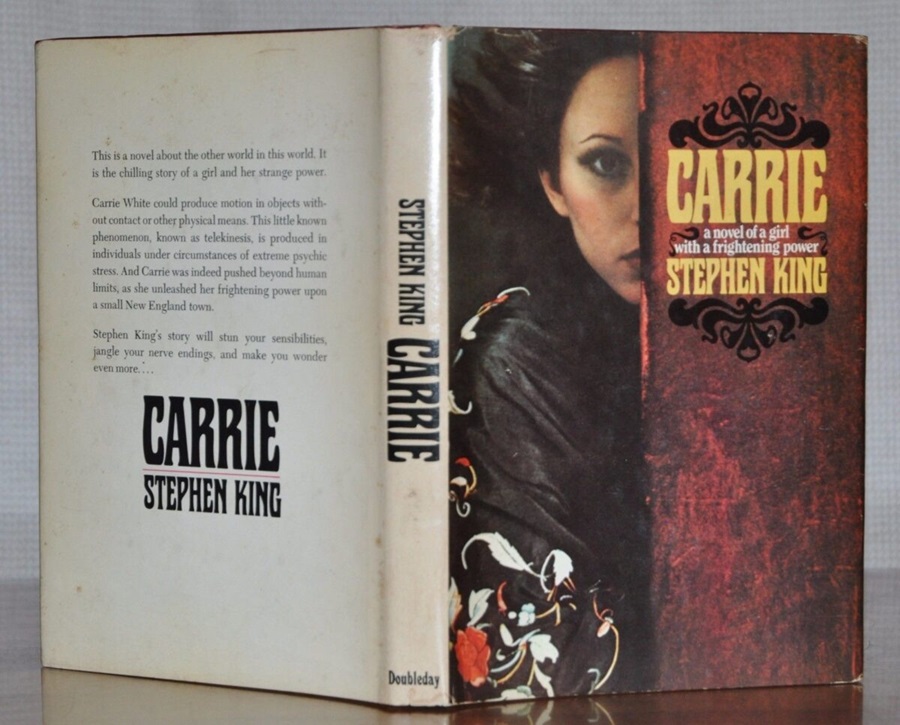

In “On Writing,” Stephen King’s nonfiction account of his career, he talks about a girl he calls Dodie Franklin. She attended his high school and, he recalls, was often bullied for wearing the same clothes every day. In their sophomore year, on the first day back after Christmas vacation, she came to school wearing newly fashionable clothes with a trendy hairstyle — but the bullying and teasing never stopped. “Her peers had no intention of letting her out of the box they’d put her in,” Mr. King writes. “She was punished for even trying to break free.”The realization that nothing could change Ms. Franklin’s social standing, coupled with a few more unfortunate examples of young women he knew, helped inform a story about a bullied girl with telekinetic powers who is pushed to her limits and who wreaks brutal revenge on her classmates and, eventually, her abusive mother. “Carrie,” Mr. King’s first published novel, was released 50 years ago, in 1974.

There have been many iterations of “Carrie” since. Horror enthusiasts will recall the classic film directed by Brian De Palma and released in 1976; there have been several remakes, most recently one in 2013 starring Chloë Grace Moretz. There was an ill-fated stage adaptation, “Carrie: The Musical,” which the TV show “Riverdale” once paid homage to. Many things have changed in the half-century since Mr. King’s novel was published, yet Carrie White remains a strikingly relevant and highly relatable figure. She raged her way to a place in pop culture’s pantheon. But why? I first read “Carrie” as a nerdy, horror-enthused 14-year-old growing up in Sri Lanka. At the library of the Christian school I attended, Mr. King’s books were extremely hard to come by, so when I saw a copy at a friend’s house, I was quick to borrow it. I vividly remember being drawn to Carrie’s wide-eyed gaze on the cover, blood trailing from her forehead and dripping down her chin. “Nobody was really surprised when it happened,” it reads in the opening pages. “Not really, not at the subconscious level where savage things grow.” I was hooked. What did Mr. King mean by “savage things”? I didn’t realize then that I would spend so much of my adult life thinking about this very question.

I’ve reached for “Carrie” many times since, and my relationship with the story has continued to shift and evolve. Like most teenagers, I suppose, I initially reacted to Carrie’s story with pure horror; I was mortified by the way she was teased, repulsed by the pig’s blood that gets dumped over her at prom and fascinated by the death and destruction she wrought in retaliation. In my 20s, when I revisited the novel, the horror I felt at her tale turned to something closer to sympathy. By that point, I’d moved from Colombo to California to Britain and then back to my hometown in Sri Lanka and had chalked up enough life lessons to understand Carrie’s suffering in a different way. Now, as a woman in my 30s, I no longer see Carrie as simply a victim to be pitied. I’ve learned to relish her rage. Her anger has inspired much of my own fiction writing and, more important, has taught me that anger, when channeled, can be an asset. This truly hit home for me in July 2022, when I joined thousands of protesters in Colombo marching against corruption and the economic mismanagement of the country’s leaders. Years of feeling powerless finally erupted. We were all angry, of course, but we used our rage as fuel.

Read the rest of Jayatissa's essay at the New York Times.

Updated: Friday, April 5, 2024 11:49 PM CDT

Post Comment | View Comments (1) | Permalink | Share This Post