BLOGGER ANALYZES ALLEGORY & SATIRE IN 'PHANTOM'

"A COMPLEX & INTERTEXTUAL SATIRE" THAT NEVERTHELESS "OPERATES INDEPENDENTLY" OF ITS REFERENCES

The insightful, unnamed blogger at

You Remind Me Of The Frame is in the midst of a two-week series of posts centered around the horror musical genre hybrid. "I’m a sucker for a horror musical," begins the

introductory post from September 1st. "I truly believe that the two genres are almost identical in the way they ask audiences to suspend belief." Today's post carries the headline, "'That’s the Hell of It!' Allegory, Satire, and Musical Horror in

Phantom of the Paradise (1974)".

The essay begins, "Phantom of the Paradise is a musical experience unlike any other, which is strange, considering how frequently it is compared to other horror musicals, particularly The Rocky Horror Picture Show (RHPS). But Phantom is a masterpiece in its own way, as is its criticism and use of allegory. The film is a cacophony, a loud and direct statement against the corrupt, sexist, and overall exploitative music industry. Its story might seem insane, but there are multiple instances where that seeming exaggeration turns out to be fairly accurate. In a time when people were not talking about the violent repercussions’ musicians were facing, Phantom addressed them head on. It was not afraid to talk about casting couches or corrupt police, even though these moments are shown through satire. The film is thus a complex and intertextual satire about the horror underlying music production."

I highly recommend heading over and reading the post in its entirety... but here is a further excerpt:

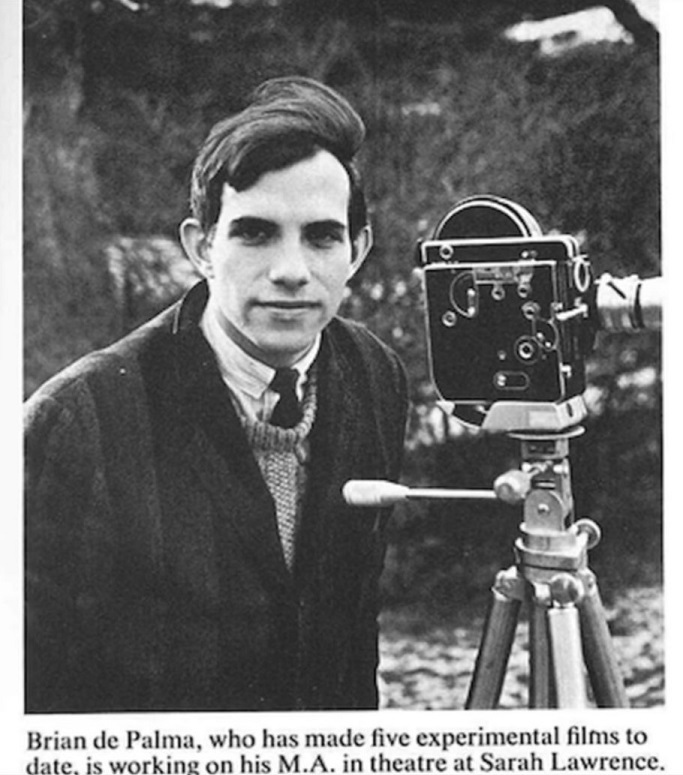

If this plot sounds familiar, it should. The film incorporates several familiar stories but places them in a modern – well, 70’s- situation. As suggested by its title, Phantom of the Paradise is an adaptation of Phantom of the Opera, but also an adaptation of Faust, the same subject which inspires Winslow’s cantata. This is just one of the ways the film focuses on mirrors and reflections, or duplication. Winslow’s music reflects these other works but also the events of the film. We see references to The Picture of Dorian Gray, Frankenstein, and the 1920 film The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, all of which are frequently cited by glam musicians and other rock musicals. These references explain why Phantom is so often compared to other projects, as it mirrors their plots and creations. Before discussing how the film operates independently, I think it would be useful to discuss why it makes these references, and why it gets compared. I first learned about Phantom of the Paradise because I was obsessed with adaptations of Phantom of the Opera. Because I stumbled across the film while searching ‘Phantom’ in IMDB, I have always seen it in comparison with other Phantom projects, specifically the way it shares its plot with Gaston Leroux’s book. De Palma’s film modernizes the text, and in doing so, says something about our society versus Leroux’s. For instance, the film transforms the competitive Carlotta into the pill popping, cocaine sniffing, and humorously ill-suited Beef. He is the wrong choice to sing Winslow’s music because he embodies a different music genre: glam. The level of excess and performance involved with glam doesn’t match Winslow’s cantata, as although both opera and glam rock are exorbitant, they approach this theatricality in different ways. The film also has a different kind of antagonist, as the Phantom character is traditionally the primary villain/antihero in the story. Not so in Phantom of the Paradise, as Phoenix is surrounded by villains who call themselves geniuses. She gets exploited by everyone, including Winslow. Its left unclear at the ending if Winslow’s sacrifice will liberate Phoenix, or if she is stuck in this toxic system. Both changes suggest that our modern world is far more complex and immoral than Leroux’s subject. Dastardly villains are no longer content with opera house basements. Now, they run the entire music industry and the poor souls within it. . . .

. . .

. . . When Swan picks Beef, the film implies that glam rock is the opposite of Winslow’s original music. Glam is loud and distracting, while Winslow’s ballad is slow and stripped back. This demonstrates that genre is ultimately meaningless to figures like Swan, its just a way to tell a song, not the song itself. While Swan is interested in the bigger picture, how it will be received, Winslow is obsessed with the components of the song, its genre and Phoenix’s voice. This summarizes the film’s position on the industry complex, as Swan is only interested in the future, not the present or past. He uses nostalgia to lure his audience but isn’t interested in what constitutes nostalgia or its various components. That is why we get a bizarre car surfer song about halfway through the film (“Upholstery”), and why The Juicy Fruits transition from rockers to surfers. Nothing about their music or image matters, its only there to entertain people momentarily. The characters switch between genres because of Swan’s mentality. That is why Swan ridicules nostalgia, noting “Who wants nostalgia anymore?”. It is just a cheap and quick way to captivate people, and none of it matters.

Swan lacks dedication to any genre or person in the same way he lacks morality. Every aspect of his industry and approach to music are horrible. Casting, production, and performance, each of these are just layers in his Dante-like inferno and network. Take “Goodbye Eddie”, a song about a washed-up musician who decides to kill himself so his record will sell, and so his sister can afford medical treatment. The lyrics claim that Eddie did a good thing, and that his suicide was valiant and admirable, rather than critiquing a system which drives people to suicide to help their family. Likewise, although they are singing about a martyr, the musicians are busy trying to assault women while singing. The song thus juxtaposes immoral actions with moral subject, a jarring comparison.

The musician’s behaviour demonstrates that the words do not mean anything, they are just singing because it’s a job. This trend continues throughout the film, as only figures like Winslow and Phoenix pay attention to the songs. Likewise, “Goodbye Eddie” makes a direct link between commodity and morality, in addition to death and success. The film suggests that music is a destructive entity, as are the people who run it. They only care about the result, not the people who make it. By associating music deals with Devil pacts, Phantom suggests that the industry is a corrupt system of legal damnation which abuses and distorts true artistry.