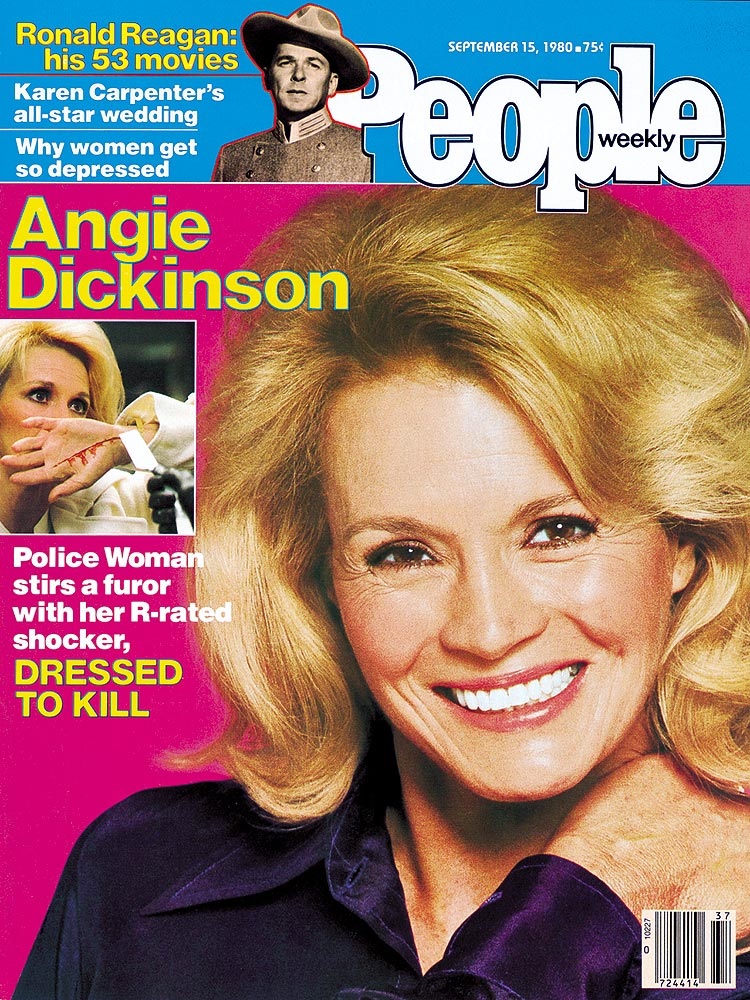

WITH HER R-RATED SHOCKER, DRESSED TO KILL

Updated: Wednesday, September 16, 2020 12:13 AM CDT

Post Comment | View Comments (1) | Permalink | Share This Post

Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | September 2020 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

| 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 |

| 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | |||

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

Listed alphabetically, The Untouchables entry on the Journal's master list reads:

This David Mamet written and Brian De Palma directed 1987 picture probably also deserves Mt. Rushmore Chicago movie status. There are not many that can check all the boxes it hits.It was almost entirely filmed here and has pivotal/famous scenes in some of the city's most iconic locations, it was a critical/commercial success, and it piles on the je ne sais quoi of Chicago attitude with the quotes to match.

In fact, The Untouchables gave us maybe the most-used/well-known movie quote in the history of Chicago. When Sean Connery, who won an Oscar for his role, is talking to Kevin Costner playing infamous lawman, Eliot Ness, famously describes increasing violence in order to bring down Al Capone's empire:

"They pull a knife, you pull a gun. He sends one of yours to the hospital, you send one of his to the morgue. That's the Chicago way!"

Brian De Palma directs this movie about kids with occult powers who go to a special Lincoln Park school and fight a government plot.

And then today, Piper De Palma posted the pic below on her Instagram. Let's follow the zoom around the room, so to speak: Brian De Palma, flanked by Susan Lehman and Piper, sits at twelve o'clock; then going clockwise, Noah Baumbach, Greta Gerwig, David Koepp, Steven Spielberg, Martin Scorsese, Jake Paltrow, Jay Cocks, and, in the center, Wes Anderson. A legendary line-up, indeed.

(Thanks to Adam Zanzie, via a Nick Newman tweet.)

What modern American director: a) Went to Columbia for college to study "math, physics, and Russian"; b) Directed the feature screen debut of one Robert De Niro in 1965; c) Was present immediately after composer extraordinaire Bernard Herrmann, having just completed recording the score for "Taxi Driver," went back to his hotel and promptly died; d) Directed Orson Welles in his first big studio picture, at the tender age of 32; e) Helped cast "Star Wars"; f) Was best buds with fellow burgeoning auteurs Marty Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, George Lucas, and Steven Spielberg after arriving in L.A. in the late '60s; and g) Went on to make no fewer than at least a half-dozen (by my unofficial count) truly extraordinary pictures?Right, well, as you may have already guessed, the correct answer is Brian De Palma, a filmmakers' sort of filmmaker, not just because of his many homages to past masters, including Eisenstein, and, of course, his beloved Hitchcock, but also because he had his own vision and worked very hard to make the movies he wanted to make, usually at the expense of the castigating suits who funded his pictures.

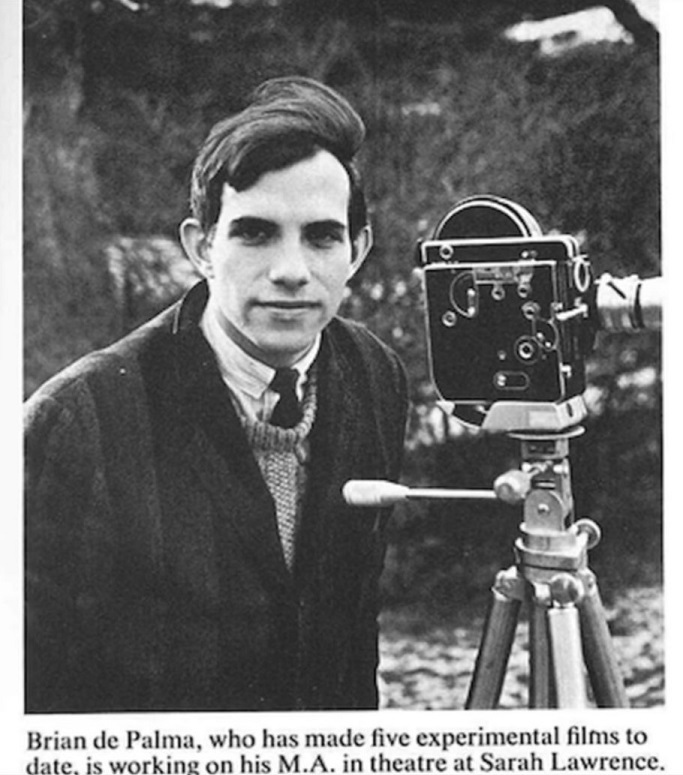

Noah Baumbach and Jake Paltrow's documentary dispenses with all but the essentials: De Palma sits in a chair and methodically works his way through his rather extraordinary career, from his earliest days, making films as part of a workshop at Sarah Lawrence College, to his biggest hits -- including "Carrie," "Dressed to Kill," "Scarface," "The Untouchables," "Mission: Impossible" -- to his worst box office misses -- "The Fury," "Wise Guys," "The Bonfire of the Vanities," "Mission to Mars," among them. Through it all, he's open and honest as to the work he's proud of, and what he sees as a failure, as well as actors with which he worked (loved De Niro, Tom Cruise, Sissy Spacek; detested Cliff Robertson, found Welles stunningly unprofessional). What's more, representing the most venerated and decorated generation of American filmmakers in history -- one, it must be restated, given vastly more studio carte blanche in the early '70s than at any other point in Hollywood's existence -- he speaks of the problems he sees with modern studio films, finds the use of CGI both sort of thrilling, and ultimately bland (correctly pointing out the directors mainly have to pack off the footage and let the effects team figure out what happens in those many, many cliched battle scenes). But he's also almost eerily optimistic, in a way that gives you a better understanding of a director who has produced a kind of schizophrenic filmography of extreme highs and bitter lows. How a man took on massive disappointment, and heavy studio beef, over and over, and keeps picking himself up and coming back to try again.

"From early masterworks such as Phantom of the Paradise to the overlooked and incendiary Domino, De Palma is gifted at crafting moments that don’t just linger, they burrow. Whether it’s a mind-bending split diopter, a startlingly vibrant color palette, or an assaultive act of violence, his films are unforgettable. This made selecting only ten shots a near-impossible task. One could select one-hundred shots from any given De Palma film and it still wouldn’t be a complete catalog of his skill. But the following ten shots are the ones that immediately come to mind when thinking about what makes De Palma the director he is."

I'll leave it to you to go to Film School Rejects to discover which shots she has chosen (with gifs included), and what she has to say about them... but, well, when you read the first one here, I think you'll see that you're in for a treat:

Hi, Mom! (1970)The Shot: A woman tests out her new camera by locating Robert De Niro‘s Jon Robin in her field of vision and zooming in on him.

The Obsession: One of De Palma’s signature components is voyeurism. In Hi, Mom!, a film very much about both active and passive forms of looking and observation, this moment highlights an intrinsic curiosity that is found across De Palma’s filmography. While aspiring pornographer Jon looks at his own equipment, this woman turns her attention to him in order to test out the zoom feature. She decides to zoom in on a stranger across the room. She remarks that he becomes blurrier the closer she zooms in, while the focus eventually adjusts as Jon turns his own camera on her.

It’s a rather insignificant moment, one that has very little bearing on the film’s narrative, but it captures some of the most prominent themes in the film. Here, the camera is a novelty, and the prospect of using it to capture footage of a stranger is a bit of lighthearted fun to the female patron, while to Jon it is a tool for invasive voyeurism. There’s a duality to the tool, one that contradicts and complicates any attempt to classify an inherent quality of the camera.

There are also contractions in its very mechanism. As the woman remarks, the closer she gets to Jon, the more the image becomes blurry. While she remains on the other side of the room, she gets a sense of proximity but loses clarity. This shot is also a remarkable comment on the impulses of both De Palma and his characters — when anyone has a camera in hand, they can’t help but aim it at another person. Sure, De Palma is a voyeur. Who isn’t?

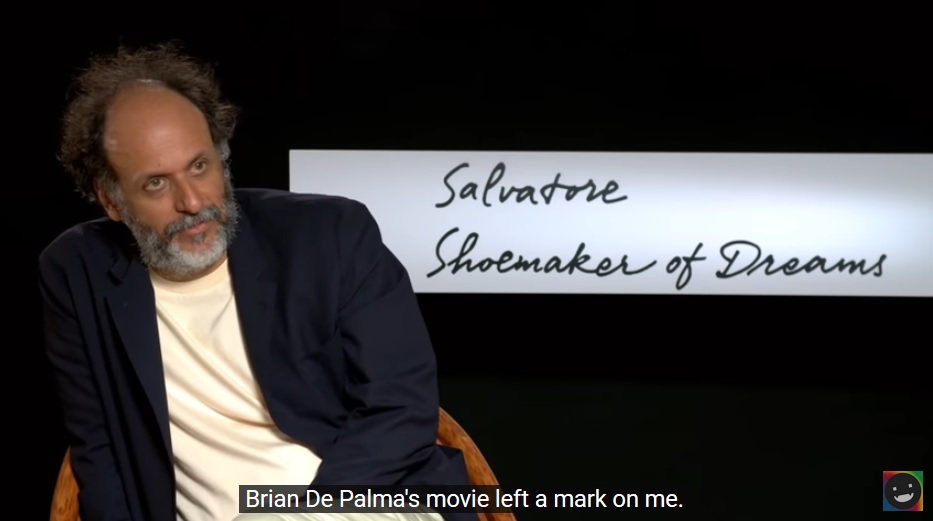

BadTaste: When you were here presenting A Bigger Splash, we talked about Suspiria. You told me about what you saw in Dario Argento's movie, and your movie actually mirrored that vision. So: what do you see in Brian De Palma's Scarface?Luca: But why are you deciding that my reference is De Palma's movie?

BadTaste: Well, I'm curious about it.

Luca: Okay...

BadTaste: More than what you see in Hawks' movie.

Luca: Well. Brian De Palma's movie left a mark on me. So it's an important movie in my imagination. The truth is that I'm interested in the character of Tony Montana. He's a symptom of the American Dream. And I think that these movies are made for their ages. My own Scarface will arrive 40 years after the previous one. I think the important thing about these movies is not the fact that they are lush and fundamental like the Brian De Palma one. The important thing is knowing that Tony Montana is an archetypal character. We won't consider the problem of the existence of a great movie before this one. I'm talking about, for example, The King Of Kings and The Last Temptation Of Christ, if we were conceiving a movie about Jesus Christ. It's an archetypal human figure. We don't have inferiority complexes about great movies made by great filmmakers. I think that Tony Montana is an extraordinary symptom of the American Dream. I think that Tony Montana righteously took from Howard Hawks' age (and remember, when that movie opened, it was accompanied by titles that said, "The filmmakers do not endorse criminal behavior"). That movie was sensational, hugely popular, probably more than De Palma's movie, in proportion. It's almost 100 years that Tony Montana affects the imagination of the audience. And this happens in part because we are attracted by what is capable of producing evil. And in part because we want to make something bigger than ourselves. It's about the dream of fulfilling, of success. This is something way bigger than Brian De Palma's direction. It's something bigger than Brian De Palma, Howard Hawks, and myself. The important things are: A) It has to be well done, the script has to be great. And it is. B) Our Tony Montana has to be current-- I don't want to imitate anything. C) This movie has to be shocking. So: I told you about Suspiria, and I kept the promise I made to you. Then I think I will surprise you with this movie, too. Brian De Palma's movie was rated R, so I want a big R on my movie, too.

Guadagnino expects his Scarface to be "timely"

Luca Guadagnino is the latest director for Scarface

The essay begins, "Phantom of the Paradise is a musical experience unlike any other, which is strange, considering how frequently it is compared to other horror musicals, particularly The Rocky Horror Picture Show (RHPS). But Phantom is a masterpiece in its own way, as is its criticism and use of allegory. The film is a cacophony, a loud and direct statement against the corrupt, sexist, and overall exploitative music industry. Its story might seem insane, but there are multiple instances where that seeming exaggeration turns out to be fairly accurate. In a time when people were not talking about the violent repercussions’ musicians were facing, Phantom addressed them head on. It was not afraid to talk about casting couches or corrupt police, even though these moments are shown through satire. The film is thus a complex and intertextual satire about the horror underlying music production."

I highly recommend heading over and reading the post in its entirety... but here is a further excerpt:

If this plot sounds familiar, it should. The film incorporates several familiar stories but places them in a modern – well, 70’s- situation. As suggested by its title, Phantom of the Paradise is an adaptation of Phantom of the Opera, but also an adaptation of Faust, the same subject which inspires Winslow’s cantata. This is just one of the ways the film focuses on mirrors and reflections, or duplication. Winslow’s music reflects these other works but also the events of the film. We see references to The Picture of Dorian Gray, Frankenstein, and the 1920 film The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, all of which are frequently cited by glam musicians and other rock musicals. These references explain why Phantom is so often compared to other projects, as it mirrors their plots and creations. Before discussing how the film operates independently, I think it would be useful to discuss why it makes these references, and why it gets compared.I first learned about Phantom of the Paradise because I was obsessed with adaptations of Phantom of the Opera. Because I stumbled across the film while searching ‘Phantom’ in IMDB, I have always seen it in comparison with other Phantom projects, specifically the way it shares its plot with Gaston Leroux’s book. De Palma’s film modernizes the text, and in doing so, says something about our society versus Leroux’s. For instance, the film transforms the competitive Carlotta into the pill popping, cocaine sniffing, and humorously ill-suited Beef. He is the wrong choice to sing Winslow’s music because he embodies a different music genre: glam. The level of excess and performance involved with glam doesn’t match Winslow’s cantata, as although both opera and glam rock are exorbitant, they approach this theatricality in different ways. The film also has a different kind of antagonist, as the Phantom character is traditionally the primary villain/antihero in the story. Not so in Phantom of the Paradise, as Phoenix is surrounded by villains who call themselves geniuses. She gets exploited by everyone, including Winslow. Its left unclear at the ending if Winslow’s sacrifice will liberate Phoenix, or if she is stuck in this toxic system. Both changes suggest that our modern world is far more complex and immoral than Leroux’s subject. Dastardly villains are no longer content with opera house basements. Now, they run the entire music industry and the poor souls within it. . . .

. . .

. . . When Swan picks Beef, the film implies that glam rock is the opposite of Winslow’s original music. Glam is loud and distracting, while Winslow’s ballad is slow and stripped back. This demonstrates that genre is ultimately meaningless to figures like Swan, its just a way to tell a song, not the song itself. While Swan is interested in the bigger picture, how it will be received, Winslow is obsessed with the components of the song, its genre and Phoenix’s voice. This summarizes the film’s position on the industry complex, as Swan is only interested in the future, not the present or past. He uses nostalgia to lure his audience but isn’t interested in what constitutes nostalgia or its various components. That is why we get a bizarre car surfer song about halfway through the film (“Upholstery”), and why The Juicy Fruits transition from rockers to surfers. Nothing about their music or image matters, its only there to entertain people momentarily. The characters switch between genres because of Swan’s mentality. That is why Swan ridicules nostalgia, noting “Who wants nostalgia anymore?”. It is just a cheap and quick way to captivate people, and none of it matters.

Swan lacks dedication to any genre or person in the same way he lacks morality. Every aspect of his industry and approach to music are horrible. Casting, production, and performance, each of these are just layers in his Dante-like inferno and network. Take “Goodbye Eddie”, a song about a washed-up musician who decides to kill himself so his record will sell, and so his sister can afford medical treatment. The lyrics claim that Eddie did a good thing, and that his suicide was valiant and admirable, rather than critiquing a system which drives people to suicide to help their family. Likewise, although they are singing about a martyr, the musicians are busy trying to assault women while singing. The song thus juxtaposes immoral actions with moral subject, a jarring comparison.

The musician’s behaviour demonstrates that the words do not mean anything, they are just singing because it’s a job. This trend continues throughout the film, as only figures like Winslow and Phoenix pay attention to the songs. Likewise, “Goodbye Eddie” makes a direct link between commodity and morality, in addition to death and success. The film suggests that music is a destructive entity, as are the people who run it. They only care about the result, not the people who make it. By associating music deals with Devil pacts, Phantom suggests that the industry is a corrupt system of legal damnation which abuses and distorts true artistry.

Director Peet Gelderblom is no stranger to editing and rummaging around in other people's materials. His award-winning short Out of Sync used the clever trick of having the images and sound run out of sync on purpose, thereby inventively changing the meaning of the images you saw. His on-line series Pretty Messed Up also turned heads with the ingenious editing and juxtapositioning of extremely differing film clips. And his fan-edit of Brian De Palma's Raising Cain, a reconstruction based on De Palma's original script, turned out to be SO GOOD, that it received De Palma's blessing as a superior version, and has been put on the recent Blu-ray releases (by Shout! and Arrow) as a "De Palma's Director's Cut".For When Forever Dies, Gelderblom had access to the movie archive of the Eye Film Museum in Amsterdam, which houses over 125 years of celluloid history, including several famous collections of unique materials. The end result is a wild mix of footage famous and unknown, live-action and animation, drama and documentary, black-and-white and color, old and n... well, less old, silent and sound... it's often bewildering and hypnotizing, and sometimes very, very funny.

There are a few pitfalls with this type of movie though, and Gelderblom can't avoid all of them. For some scenes he uses long takes from famous films, like Carl Theodor Dreyer's silent classic The Passion of Joan of Arc and Benjamin Christensen's eclectic Häxan: Witchcraft Through the Ages. The use is not sacriligious, and Peet Gelderblom's reverence for these titles is evident, but these shots do take you out of the story, and sometimes make you wish you were watching the original source instead. Also, the final message isn't really all that groundbreaking, and at 109 minutes, it outstays its welcome a bit at some points. I'm tempted to say "When Forever Dies could use some editing". But that would be a bad joke; the film and its length are obviously the result of a massive labor-of-love by an editor who is devoted to cinema.

All in all I was intrigued and entertained. And it does instill a terrifying truth that there is still so much footage, be it of classics or of obscurities in hidden vaults worldwide, that I haven't seen yet and maybe never will...