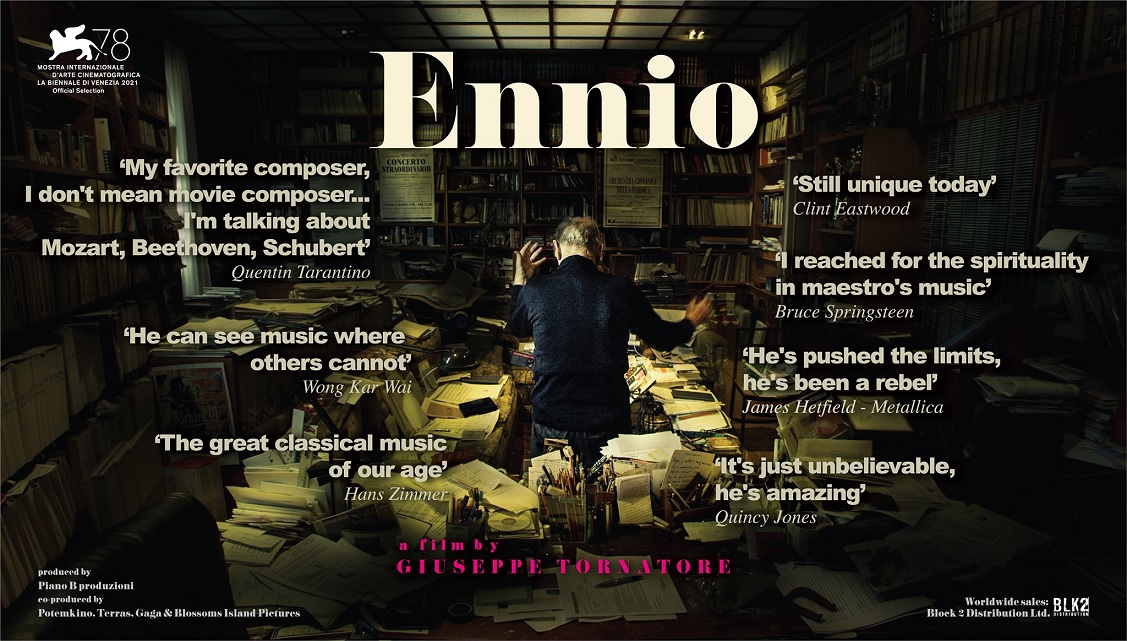

documentary that had its world premiere at this year's Venice Film Festival. Here's a portion of the review:

Of all the filmmakers who owe debts to the great Ennio Morricone, surely few owe as much as Giuseppe Tornatore: 1988’s Cinema Paradiso was a crowd-pleaser for many reasons, but would’ve had a harder time becoming a global hit without Morricone’s romantic, nostalgic score. Tornatore worked with the composer many times after that first collaboration, and is well positioned to offer the career-capping Ennio, which arrives barely a year after Morricone’s death. Happily, the film is more than a greatest-hits rundown (and at nearly three hours, it had better be): In addition to nuts-and-bolts musicology, it offers real engagement with a complicated character, endearingly stubborn and self-effacing, whose inventiveness changed both his chosen field (“absolute” music) and the one, film scoring, he entered only reluctantly.

The maestro sits onscreen for much of the film, alert behind his giant spectacles, telling stories about a career he’d intended to be entirely different — even after he gave up a boyhood ambition to be a doctor. (His father, a professional trumpeter, insisted that little Ennio should follow the same path.)

Morricone recalls the humiliation of playing for food during the occupation of Italy in World War II. His play-for-peanuts experiences may have left a visible mark, because when he entered a program to study composition, the young man was at first allowed to write only dance tunes. Morricone craved the approval of his mentor, the composer and teacher Goffredo Petrassi — he still remembers the grades he got on assignments — and he did make headway in the academic arena, eventually helping to form an avant-garde collective inspired by John Cage.

But he was always doing commercial work as well, staying up all night to crank out arrangements for TV shows that didn’t credit him by name. This led to arrangements for pop singers, and Tornatore shows us many enjoyable examples of what Morricone’s contemporaries are describing in interviews: Where previous arrangers simply wrote orchestral parts to follow a song’s chords, he was inventing something new, giving the orchestras much more to do, and adding elements no pop producer at the time would have imagined using, from tin cans to typewriters.

The film’s brief but delightful tour through these bing-bongy pop tunes, enriched by interviews with Italian stars like Gianni Morandi, suggests that a very enjoyable film (if one appealing to a more narrow audience) could be made on these years alone. But that’s not why we’re here, of course. It’s time to start whistling.

Morricone composed scores for two Westerns under a pseudonym, not wanting to be associated with the genre, before teaming up with Sergio Leone. (The two were surprised to realize they’d been classmates in elementary school.) The director took him to a Kurosawa picture to explain what he had in mind, and the rest is spaghetti.

The doc’s look at A Fistful of Dollars is the first of several places in which Morricone explains how he borrowed from his own work, repurposing an arrangement he’d done for a country song. His work on that movie is also a key example of his putting his foot down — though not the first, as we’ve already heard how he swore he’d quit his conservatory if they didn’t let him study under Petrassi. When Leone intended to use a Degüello from another movie in a key showdown scene, Morricone was so offended he threatened to quit. Leone backed down.

Morricone would lose some artistic conflicts, but it seems they were often occasions on which he underrated his own work. When he sent Brian De Palma nine ideas for a victory theme in The Untouchables, he told the director, “Please don’t choose number six.” But number six is in the movie, and it’s hard to imagine any music that would serve the scene better. He also initially refused to write music for The Mission, claiming that Roland Joffé’s images were so beautiful he could only make things worse. (Again, Ennio: Wrong.)

But for serious self-deprecation, you have to hear Morricone claim that he “hates melody.” Other composers interviewed here (tons of them, in the film world and outside it) are astonished at this idea, coming from someone who has created so many memorable melodies. But there are only so many ways tones can be ordered, and Morricone calmly says, “I think that we are out of melodic combinations.” Good thing he had so many other compositional tools to work with.