FLASHBACK LOOK AT 'PASSION' AMIDST CALLS FOR RETURN OF THE EROTIC THRILLER GENRE

Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | September 2021 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

| 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 |

| 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | ||

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

If you spend any amount of time online, you’ve probably engaged in — or, at the very least, come across — conversations about the supposed politicization of popular media. Whether it be meddling right-wingers or snooty leftists, everyone seems to be under the impression that, for better or worse, genre films have evolved to reflect the increasing awareness of environmental issues, economic inequality, and race and gender politics that characterize our turbulent times. The horror genre in particular has become the target of much discussion between recent remakes of existing IP such as this year’s CANDYMAN and last year’s THE INVISIBLE MAN, the widespread acclaim of diverse new creators like Jordan Peele, and the wave of less successful knockoffs his films seem to be inspiring. Although many of these themes have certainly become increasingly overt in recent years, horror media has always been rife with blistering social critique, and the 1970s were proof of that. Brian De Palma’s psychosexual horror-thriller SISTERS is proof of that too.Released in 1972, four years prior to his meteoric success with CARRIE, SISTERS remains a somewhat underrated gem in De Palma’s filmography, which also includes SCARFACE, BLOW OUT, PHANTOM OF THE PARADISE, and the first MISSION: IMPOSSIBLE among its many hits. Taking place in Staten Island, the movie follows a woman who attempts to investigate a murder case that goes ignored by the police. Suspecting her neighbor of the crime, she falls into a tangled web of dark secrets concerning said woman’s medical history and her caustic relationship to a mysterious twin.

There are several reasons De Palma’s fourth-most-popular horror scratches an itch few films can satisfy for me. For starters, its social implications feel as relevant as ever. Spoiling as little as possible, the man (Lisle Wilson) whose murder our protagonist Grace (Jennifer Salt) witnesses, is black. A hard-hitting journalist who’d previously written about corruption in the local police force, her claims are brushed aside by the detective who does not make an attempt to properly search the neighbor’s apartment for a body. He constantly belittles Grace and threatens to have her arrested for petty charges if she doesn’t lay off. The man’s race is brought up many times over the course of the film, with Grace implying that the police are racist for not taking the murder seriously and instead siding with the white woman (Margot Kidder) she accused of deadly assault.

Unbeknownst to the other characters, said white woman, Danielle, suffers from an undisclosed psychiatric illness, and lives under the medical and emotional care of her controlling husband, Emil (William Finley). Like in Alfred Hitchcock’s PSYCHO, the initial murder victim is followed closely during the film’s first act, which establishes him as a decent man unfazed by the microaggressions he undergoes in his day-to-day life until he is brutally killed off. As the story progresses, it becomes clear that the characters are being failed by what the film portrays as oppressive social and structural forces meant to protect them — resulting in a domino effect with catastrophic consequences.

SISTERS is also just a treat for movie and history buffs. As a big Hitchcock junkie, there are few things I love more than a good modern retelling of his work, from MANHATTAN MURDER MYSTERY (1993) to STOKER (2013). SISTERS is unique in that it pays homage to the revolutionary narrative and audiovisual techniques from the Master of Suspense’s entire career through obvious references to scenes from his most iconic films.

Stow's co-host, Joey Bauer, mistakenly tells special guest Craig Leman that De Palma has never written any of the screenplays to his movies, so you can see right away that while their discussion of De Palma's films seems thoughtful and intelligent, it is not exactly fully-informed, nor well-researched. Here's the episode description:

Brian De Palma has been called a genius and a hack, but you can't deny that he makes a memorable film. This week, joined by special guest Craig Leman, we dig into De Palma's filmography to talk about his sleazy atmospheres, signature visual style, and confounding depiction of women.Spoiled in this episode: Blow Out, Dressed to Kill, Body Double, Redacted.

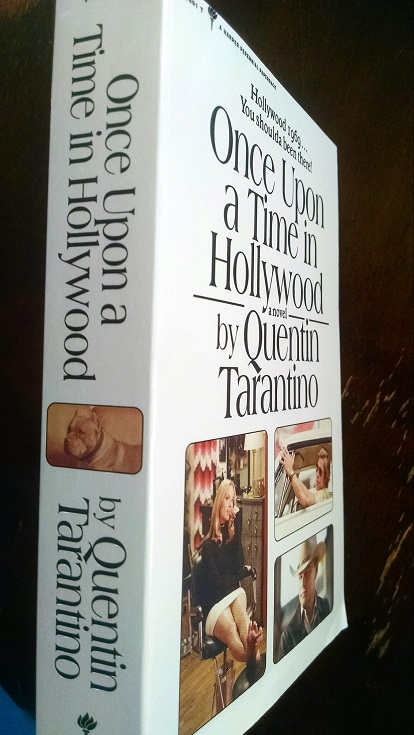

Once Upon A Time In Hollywood is, at its heart, a book about the sadness and excitement of expectation: Sharon Tate, the next-big-thing actor with her unborn child; Aldo Ray, a washed-up alcoholic with his own kind of dignity; even Manson feels more like a relatable kind of loser, trying to make it big as a hippie folk singer, than the electromagnetic pulse powering a murderous sex-and-bullshit cult. At one point the book quotes the film critic Pauline Kael: “In Hollywood you can die of encouragement.”It’s the losers, I think, who have Tarantino’s heart. Maybe that’s why [Cliff] Booth’s education in cinema feels so real. “I think it’s the solitary experience he ends up liking,” says Tarantino, turning reflective. “Which, actually, is kind of interesting. I hadn’t thought about it before – but that was, for the most part, you know, me. From, like, 14 to 22 or 23, I saw so many movies. But it was rare, unless the movie was a huge hit, that I saw something other kids in school saw or my family saw. For the most part, I’m seeing a whole lot of movies and I’ve never talked to anybody about them.”

The man GQ is speaking to today sounds blissfully happy, revelling in the joys of new parenthood. (He says he does bath time, but not nappies.) It’s been a slow growth towards contentment from the “piss and vinegar”.

“I think that’s the goal,” he says, laughing, “and most of us more or less achieve it.” But the young Tarantino was alone in his obsession. “It was a completely solitary experience. Whatever I felt about it, and however much I liked it, it was unexpressed.”

After that electric loneliness in the dark theatre, Tarantino would cut out magazine clips from his favourite music and movie critics and stick them into organised scrapbooks. “So I’d have my Pauline Kael books, my Stanley Kauffmann book, my Michael Ventura book.” Kael remains a guiding light. He not only owns all her books, but he also buys every different edition he sees. Fans have long wondered if Tarantino would ever get round to some of the projects he’s teased: a movie about the Vega brothers; a Silver Surfer film; a third Kill Bill. There are a few ideas today – the most surprising being that he’d like to write a novelisation of someone else’s movie – but the great forthcoming Tarantino work, for my money, will be a book of film reviews, slated for release in the next few years. Who wouldn’t want to read that?

Beyond that, there are big books of essays that he has been adding to for decades and which he can never seem to finish, on the work of filmmakers such as Brian De Palma, Sergio Corbucci, Don Siegel and Robert Aldrich. “I don’t think I’ll finish them,” he says, laughing. “They’re sitting un-typed in a drawer.” He has other plans – not settled yet, but vague, floating enticements that might grab him. He says he can see himself doing a novelisation of True Romance or Reservoir Dogs. What about – it seems so obvious – making Pulp Fiction into pulp fiction? A pause. “Nah, that doesn’t interest me.”

The answer is immediate. Because he knows instinctively, by this point, how to listen to his instincts, the ones that took him to where he is today. Before the mountain of paper, the one-handed typing, the rewrites and edits and inevitable accommodations with practicality, every project starts with an idea, an interior excitement, something he’s wanted to do for a long time, something that sparks the same sense of momentum he felt as a young guy adding dialogue to other people’s movies – that pregnant sense of direction and certainty. So he sits down to write. Very quickly, almost immediately, he knows if he’s on to something.

“I know within the first couple of scenes: I’m gonna finish this. This is it. This is the next one I’m doing. I started doing it and I was right.”

Brian De Palma's "Obsession" is an overwrought melodrama, and that's what I like best about it. There's no doing this sort of thing halfway, and De Palma knows it: We get gloomy vistas down wet Italian streets, and characters running toward each other in slow motion, and low-angle shots of tombs, and romantic music breaking suddenly into discordant warnings, and -- best of all -- a surprise ending which manages at the same time to be totally implausible and totally satisfying.The movie opens in New Orleans at a party celebrating a 10th wedding anniversary: Michael and Elizabeth Courtland are still deeply in love, so right away we know they're in trouble. A butler moves through the room with drinks on a tray, and as he walks toward the camera his jacket hitches up and we get a huge close-up of a gun tucked into his belt. There's ominous music on the soundtrack and no wonder -- Michael's wife and daughter are about to be kidnapped.

A ransom note demands $500,000, but Courtland allows himself to be talked into a harebrained scheme by the police. They spike the money with a little radio transmitter and follow the signals back to the house where the kidnappers are holed up. There's a confused escape, the police chase the getaway car, it crashes into a gasoline truck and in the resulting explosion, the wife and daughter are killed. At least that's what Michael Courtland believes for 18 long years, during which he erects an enormous monument in an otherwise empty cemetery.

But then, during a business trip to Italy, he visits the church in Florence where he first met his wife. And there on a scaffold, mixing some paint and helping with a restoration project, is his wife! She looks exactly the same as she did 18 years ago. There is a courtship, a romance, plans for marriage and a return to New Orleans. And then Paul Schrader's screenplay starts a series of incredible double-reverses and shocking revelations, which of course it wouldn't be fair for me to reveal.

The ending, as I've suggested, is totally implausible -- we can think of at least a dozen questions in the last five minutes alone -- but who cares? De Palma and Schrader, and Bernard Herrmann with his beautifully overdone music, and Cliff Robertson and Genevieve Bujold with their mutual obsession, are all playing this material as broadly as possible. This is a 1940s melodrama out of the CBS Radio Mystery Theater by way of a gothic novel. If you want realism, go to another movie.

Material like this needs a certain tone, and De Palma finds it. He starts with two of the most romantically decadent cities on earth (New Orleans and Florence - although Venice would have been better), and then he lets his sound track drip with portentous music and his characters roam through deserted and vaguely menacing locations. The photography, by Vilmos Zsigmond, is darkly, richly sinister: as two men sit talking in a Florentine cafe, the camera changes focus as it sweeps from one to the other so that we're forced to look beyond them into a square and wonder who we'll see there.

Robertson's first visit to the church, in which the camera's deep focus makes him seem to climb those stairs forever, is another nicely disturbing visual moment. And, in a movie that owes a lot to the Hitchcock style, there are a few well-chosen exact quotations from the Master (as when Genevieve Bujold tells the housekeeper: "There's a door upstairs that's locked. Where is the key?" And then . . . well, You know how these things develop.)

The movie's been criticized as implausible and unsubtle, but that's exactly missing the point. Of course the ending is out of a lurid novel, and of course the music edges toward hysteria, and of course Robertson goes from mad to worse (wouldn't you, if you saw a ghost?). I don't just like movies like this; I relish them. Sometimes overwrought excess can be its own reward. If "Obsession" had been even a little more subtle, had made even a little more sense on some boring logical plane, it wouldn't have worked at all.

Today in 1978 I saw a favourite Brian De Palma, THE FURY, at the Century Preview Theatre. It was at this screening I sat behind Amy Irving, didn't know, raved about her performance, and she turned to me to say thanks. Classic!

Perpetual room tone: Gate Notting Hill IIRC. Pipe-smoking lunatic in the audience challenged De Palma.Neil Irving: Yes, it was an 11.15pm screening. That must have been a very late-night Q&A?!

Perpetual room tone: De Palma was ultra-patient with dumb/fawning/rambling "questions" (mine included)

When BLOODY MAMA opened at my dad’s Plaza Theater in Asheville, NC, in March 1970, AIP sent a 26-year-old actor who played one of Shelley Winters’ sons in the movie. He drove a vintage 1930’s car like the one in the film. He parked the car out in front of the theater, right under the marquee, for photo ops with the local newspaper and TV station. He signed autographs but nobody knew who he was. At age 13, I said to him, “It’s so cool to have a real-live movie star at my dad’s theater.” He smiled sardonically and said, “I’m just an actor, kid. Shelley Winters is the star.” My father and I took him to lunch and I was riveted as he talked about working for director Roger Corman — whom I idolized for all his Vincent Price / Edgar Allan Poe movies. I wanted to ride off into the sunset with this guy but after lunch, he left me in the dust. Five years later, in 1975, this same guy won an Oscar for Best Supporting Actor in THE GODFATHER: PART II. His name was Robert De Niro.