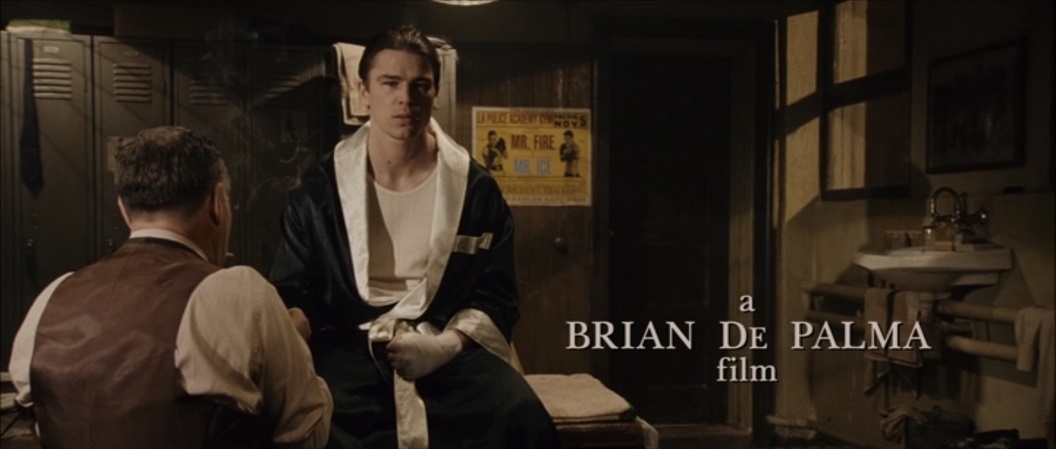

SCOUT TAFOYA COUNTS 'THE BLACK DAHLIA' AMONG HIS FAVORITE DE PALMA FILMS

As we're still vibing on the 15-year anniversary of Brian De Palma's stunningly-personalized film adaptation of James Ellroy's The Black Dahlia, it's worth noting a mention of the movie from filmmaker and critic Scout Tafoya. Reviewing the new Apple TV+ sci-fi series Foundation for Cult of Mac, Tafoya delves into the backgrounds of its showrunners:

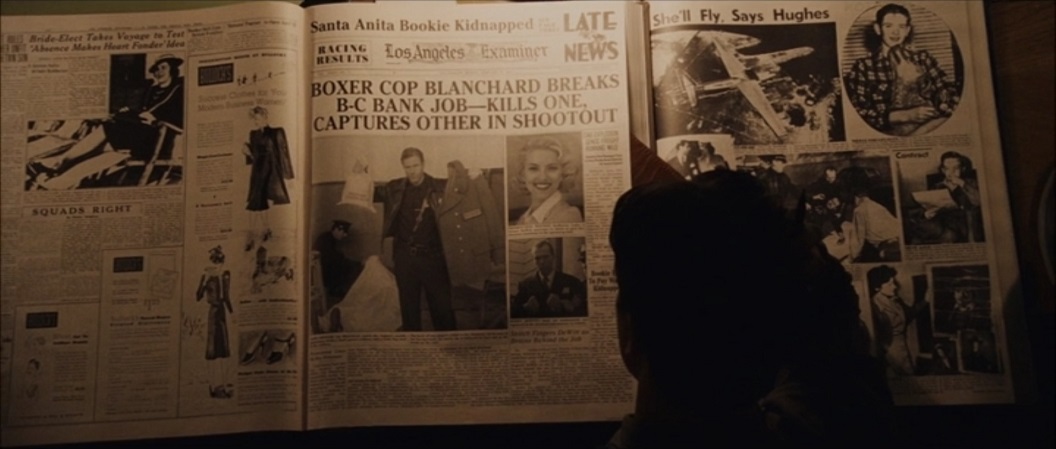

Foundation doesn’t prove as fearless about its antique roots. But in keeping the character of psychohistory alive (mathematics as a bulwark against religion, or at any rate a worthy twin), you can see Asimov with his sideburns and his new age techno-humanism in the great big towering storylines anyway. They’ve just been filtered through the aggressively middlebrow vision of showrunners David S. Goyer (Batman Begins, The Dark Knight) and Josh Friedman (Emerald City).Friedman has done some interesting work in his time. But you’d be hard-pressed to locate anything as concrete as a sensibility from his shows, beyond a sort of desire to build great big worlds out of existing IP. He wrote the movie The Black Dahlia, which ranks as nobody’s favorite adapted screenplay, though I confess it’s among my favorite Brian De Palma movies.

Goyer is more troublesome. Having written both the exciting and edgy Blade and Christopher Nolan’s baggy and self-important Batman movies, and helping ensure the enduring monopoly of DC and Marvel comics at the U.S. box office, he was then given free reign to do whatever he wanted. This despite his having directed the abysmal likes of Blade: Trinity and The Unborn.

I can’t fully bring myself to write off Goyer because he seems to want to make better films than he frequently produces. Plus, once upon a time he wrote the excellent Dark City, one of the great out-of-nowhere science fiction movies made during my lifetime. (That’s the kind of thing Asimov probably would have liked.)

Back in 2014, Tafoya created a video essay about De Palma's Phantom Of The Paradise for his video series, The Unloved. The series takes films that were received indifferently upon initial release and reveals the artistry that seemed to be overlooked in the critical and public dismissals of their time.

"Cult movies usually have to do something wrong in order to miss out on a first-run audience," Tafoya states in the video. "Idiosyncrasies and eccentricities pile up, and only a handful of people can see them as integral to the film's success as a crowd-pleasing oddity. In the case of Phantom Of The Paradise, the indifference that greeted it from critic and public alike seems much more baffling than its continued success in Winnipeg.

"It's easy to why Rocky Horror failed with mainstream audiences at first. It's entirely too pleased with itself, and features nothing in the way of sex or violence that audiences couldn't find in movies without self-conscious glam-rock all over the soundtrack. Phantom Of The Paradise had something to say, not to mention something to prove. Though it's rarely lumped in with many of its landmarks, the Phantom came out of the New Hollywood movement. By 1974, American artists were finally digging in and starting to take advantage of the creative autonomy offered by more adventurous studios. 1974 was a watershed year in particular, because it was when passion projects started flowing out of major studios. Directors were taking immense formal risks left and right, telling dark stories in daring ways, bowing to no one but their muse. There were huge successes, films that changed everything. And then there were films like Phantom Of The Paradise.

"Up until this point, Brian De Palma had been making bizarre little movies that mixed Godard and Hitchcock with abandon. Phantom Of The Paradise was his biggest film to date, and it remains his best. Perhaps sensing that he was the right man to make a crazed irreverent hash of classic literature, he grabbed his own pet influences to make a film that did for rock and roll what fellow enfant terrible Ken Russell had been doing for classical music."