"I DON'T THINK I'LL FINISH THEM - THEY'RE SITTING UNTYPED IN A DRAWER"

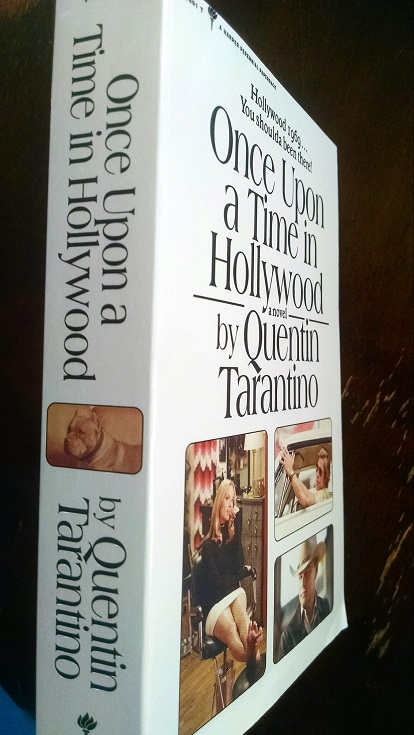

As Quentin Tarantino's first novel is published, GQ's John Phipps has a profile piece in which some other QT writings are mentioned:

Once Upon A Time In Hollywood is, at its heart, a book about the sadness and excitement of expectation: Sharon Tate, the next-big-thing actor with her unborn child; Aldo Ray, a washed-up alcoholic with his own kind of dignity; even Manson feels more like a relatable kind of loser, trying to make it big as a hippie folk singer, than the electromagnetic pulse powering a murderous sex-and-bullshit cult. At one point the book quotes the film critic Pauline Kael: “In Hollywood you can die of encouragement.”It’s the losers, I think, who have Tarantino’s heart. Maybe that’s why [Cliff] Booth’s education in cinema feels so real. “I think it’s the solitary experience he ends up liking,” says Tarantino, turning reflective. “Which, actually, is kind of interesting. I hadn’t thought about it before – but that was, for the most part, you know, me. From, like, 14 to 22 or 23, I saw so many movies. But it was rare, unless the movie was a huge hit, that I saw something other kids in school saw or my family saw. For the most part, I’m seeing a whole lot of movies and I’ve never talked to anybody about them.”

The man GQ is speaking to today sounds blissfully happy, revelling in the joys of new parenthood. (He says he does bath time, but not nappies.) It’s been a slow growth towards contentment from the “piss and vinegar”.

“I think that’s the goal,” he says, laughing, “and most of us more or less achieve it.” But the young Tarantino was alone in his obsession. “It was a completely solitary experience. Whatever I felt about it, and however much I liked it, it was unexpressed.”

After that electric loneliness in the dark theatre, Tarantino would cut out magazine clips from his favourite music and movie critics and stick them into organised scrapbooks. “So I’d have my Pauline Kael books, my Stanley Kauffmann book, my Michael Ventura book.” Kael remains a guiding light. He not only owns all her books, but he also buys every different edition he sees. Fans have long wondered if Tarantino would ever get round to some of the projects he’s teased: a movie about the Vega brothers; a Silver Surfer film; a third Kill Bill. There are a few ideas today – the most surprising being that he’d like to write a novelisation of someone else’s movie – but the great forthcoming Tarantino work, for my money, will be a book of film reviews, slated for release in the next few years. Who wouldn’t want to read that?

Beyond that, there are big books of essays that he has been adding to for decades and which he can never seem to finish, on the work of filmmakers such as Brian De Palma, Sergio Corbucci, Don Siegel and Robert Aldrich. “I don’t think I’ll finish them,” he says, laughing. “They’re sitting un-typed in a drawer.” He has other plans – not settled yet, but vague, floating enticements that might grab him. He says he can see himself doing a novelisation of True Romance or Reservoir Dogs. What about – it seems so obvious – making Pulp Fiction into pulp fiction? A pause. “Nah, that doesn’t interest me.”

The answer is immediate. Because he knows instinctively, by this point, how to listen to his instincts, the ones that took him to where he is today. Before the mountain of paper, the one-handed typing, the rewrites and edits and inevitable accommodations with practicality, every project starts with an idea, an interior excitement, something he’s wanted to do for a long time, something that sparks the same sense of momentum he felt as a young guy adding dialogue to other people’s movies – that pregnant sense of direction and certainty. So he sits down to write. Very quickly, almost immediately, he knows if he’s on to something.

“I know within the first couple of scenes: I’m gonna finish this. This is it. This is the next one I’m doing. I started doing it and I was right.”