FROM CARRIE TO CAIN TO ETHAN HUNT

Updated: Thursday, April 29, 2021 6:12 PM CDT

Post Comment | View Comments (1) | Permalink | Share This Post

Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | April 2021 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

| 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 |

| 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | |

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

This three-hour Cinema DNA lecture/discussion, led by Robert C. Cumbow, will examine a few of the films that owe the greatest debt to Vertigo and have done the most to honor its continuing place in film culture. Among the films to be discussed-in passing or at length-are works as diverse as Chris Marker's landmark short film La Jetée and his feature-length meditation on memory, Sans Soleil, which works in part as a commentary on the staying power of Vertigo; Brian DePalma's Obsession; Robert Aldrich's The Legend of Lylah Clare; Francois Truffaut's Mississippi Mermaid; Christian Petzold's stunning Phoenix; and several others. Some of the films will be represented by selected clips. There may be an occasional spoiler; but whether you have seen all, some, or only a few of the many films influenced by Vertigo, come and join the discussion, and expand and enrich your appreciation of the power that Hitchcock and Vertigo brought to the cinema.

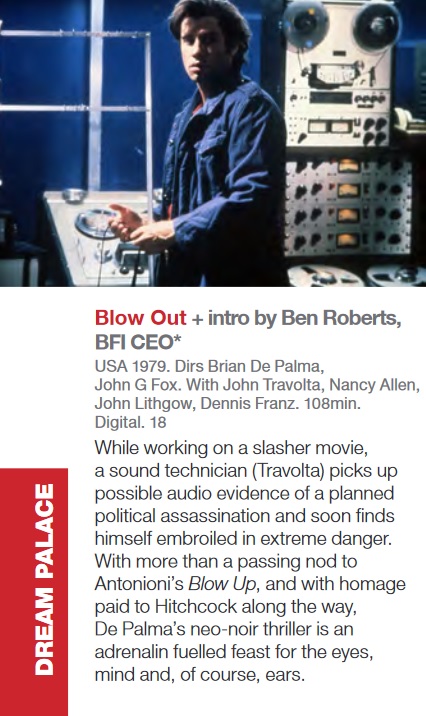

The pandemic has been traumatising on so many levels. One of the positives of the lockdown experience was a sense of communities supporting one another. We’ve been hearing from a rising tide of people who are missing going to the cinema, despite the speculative media narratives around whether or not the global pandemic would be the death of movie-going – something of a wearisome ‘old chestnut’ for some of us. It’s okay to love watching films at home, and thank goodness for streaming platforms – how would we have got through the pandemic without them? Being a movie-lover does not require us to enter a binary state that pits streamers against cinemas. BFI Player is full of amazing films and you can watch them all for a fiver a month. It’s not one or the other, it can be both, it can be all. Such was the sentiment around the inevitable impact of COVID-19 upon cinemas, that we witnessed a positive, heartfelt call to arms from the film community. Edgar Wright listed his 40 favourite cinema experiences for Empire magazine, and our own editorial campaign in Sight & Sound, ‘My Dream Palace’, celebrated the form and our venues. It’s a series of love letters to cinemas from an extraordinary cohort of cinema luminaries, designed to celebrate and ‘keep a light burning’ for cinemas while they’re closed. We all want to be back sitting in the dark together, feeling these stories become dreams on the big screen. We want to be back in our ‘safe harbours’, to borrow Mark Cousins’ phrase, and now we can be. The following is a selection of films chosen by participants of our Dream Palace campaign, and some BFI extended family. We asked people to select the film that they would most like to see at BFI Southbank – and what a selection it is! A wonderfully eclectic mix to look forward to. One thing’s for sure, they’re all going to be glorious to see on our dreamy big screens.

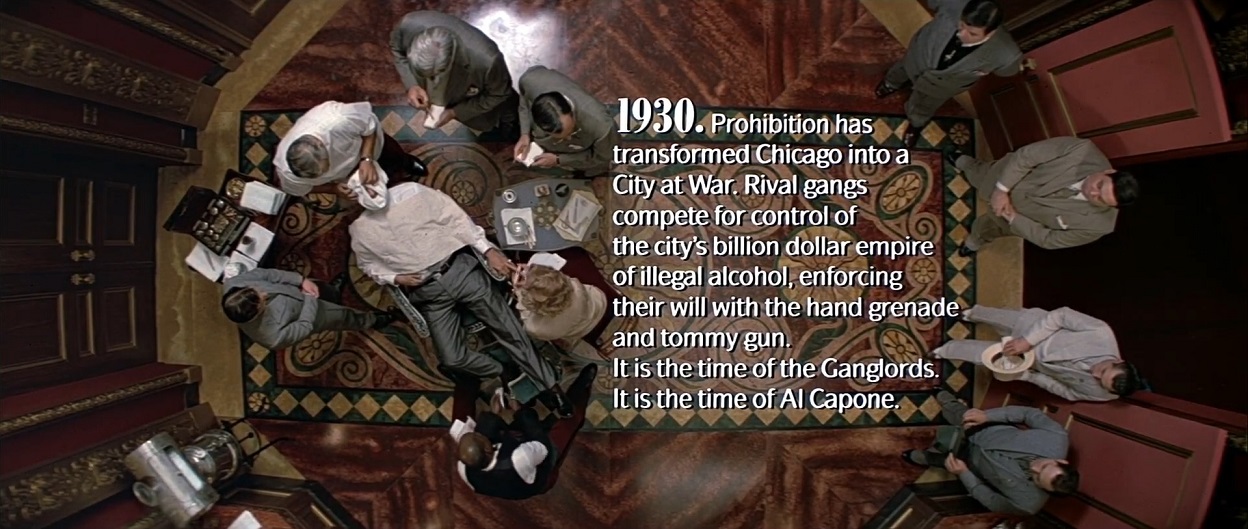

From a TIME magazine article by Richard Corliss, June 22, 1987:

Dawn Steel, president of production at Paramount, recalls that Mamet's first draft was an "outline, very sparse." How sparse? Capone was hardly in it. To flesh out Mamet's bare-bones script, Steel and her boss Ned Tanen wanted De Palma. "In the past," she says, "Brian hasn't chosen the material that was worthy of him and that he was worthy of. He was making homages to Alfred Hitchcock. This one is a homage to Brian De Palma -- he felt it instead of directing it. With this picture he became a mensch." It surely marked a ! change from the snazzy, derivative thrillers (Carrie, Body Double) and dope operas (Scarface) that made him notorious. The new picture would be neither parody nor eulogy; it would be the story of a straight arrow, told with a straight face.There are the familiar De Palma touches: lots of photogenic blood, a gorgeous tracking shot that leads our heroes from euphoria to horror, an endlessly elaborate set piece reminiscent of the Odessa Steps sequence in Potemkin. But the director's chief contribution is to the film's handsome physical design. "I wanted corruption to look very sleek," he says. "Some people in positions of power with ill-gotten money insulate themselves with over-the-top magnificence. They buy paintings and expensive clothes. And deep inside they know they're cheats and killers."

Visual Consultant Patrizia Von Brandenstein (Amadeus) accompanied De Palma to Chicago to devise the film's production design. "I thought about these four unlikely little guys going up against the mythic monolith of Capone," she says. "So I used architecture that showed mass and power: the Chicago Theater for the opera house, Louis Sullivan's Auditorium Building for Capone's hotel, a spiffed-up Union Station for the Odessa Steps sequence. Fortunately, Paramount let me really run wild."

I get hung up on this stuff, too, though it’s easy to easy to overlook the lies, narrative or visual, for other compensations. “The Untouchables,” for example. Director Brian De Palma and Chicago-born screenwriter David Mamet filmed a lot of their 1987 Eliot Ness/Al Capone saga here, at Union Station, or on the Michigan Avenue bridge over the Chicago River.Factually the film is full of it, and I don’t mean facts. It makes stuff up. (It’s a fictional narrative based a little bit on fact; in other words, not a documentary.) At one point, Mamet bailed on rewrites ordered up by producer and fellow Chicago native Art Linson involving Ness tossing gangster Frank Nitti off a rooftop.

It’s a pretty dumb scene, but “The Untouchables” has many I love. Some take glorious advantage of filming here, in the city where the story is set, as in the simple establishing shot of Kevin Costner, Sean Connery, Andy Garcia and Charles Martin Smith crossing LaSalle Street, backed by the 44-story wonder that is the Chicago Board of Trade Building. That famous corridor has never been given grander screen treatment, with the possible exception of “The Dark Knight.”

Chicago as an authentic 20th-century screen entity has a sadly incomplete history, largely thanks to Richard J. Daley. In 1957, NBC-TV premiered the Chicago-set police drama “M Squad,” starring Lee Marvin as the tough guy who, decades later, inspired Frank Drebin in “Police Squad!” and the subsequent “Naked Gun” movies.

Daley and then-Police Commissioner Timothy O’Connor had no love for it. In their eyes, “M Squad” made Chicago look bad. A 1959 epsoide depicted a cop on the take, which made Daley vow never to make special accommodations for outside film crews. That same year, Marvin told TV Guide: “We shoot locations, twice a year. No permit, no cooperation, no nothing. They don’t want any part of us .… Any public building, but nothing else, no stopping traffic. We shoot it and blow.”

A decade later “Medium Cool,” with its culminating scenes filmed during the downtown Chicago melee during the August 1968 Democratic National Convention, gave the city and the mayor another image problem. Daley let John Wayne and “Brannigan” film here, in the mid-’70s, but only when the Jane Byrne mayoral years commenced did Hollywood feel welcome and free to take over Chicago’s streets and beat things up a little, the way the 1980 smash-‘em-up “The Blues Brothers” did.

“Judas and the Black Messiah” may not give you any of the real or period-approximated Chicago of the Fred Hampton years, but Cleveland turned out to be a reasonably effective substitute. Oddly, it’s “The Trial of the Chicago 7″ that looks and feels more fraudulent in terms of atmosphere, even though Sorkin filmed some scenes here.

Moral of the story? You never know. Filming “Holidate” here wouldn’t have saved “Holidate.” And, though I love it, the Chicago-set and Chicago-filmed “Widows” apparently had just enough script issues and knotty storylines to prevent it from connecting with the mainstream audience it deserved.

We’ll close with a little-known story behind the Union Station sequence in “The Untouchables.”

At the time, cultural historian [Tim] Samuelson was working for the Commission on Chicago Landmarks, helping with location scouting for De Palma’s crew. They needed, as he recalled, “a building that looked like a 1920s hosptial with a lot of stairs in front of it, plus a landing.”

Samuelson told them about a couple of churches he knew, here and there. Those might work, he said. How about a church instead of a hospital? No, doesn’t fit the script, the crew said. Well, the only other place, really, is Union Station, Samuelson replied.

A day or two later: “Thanks a lot,” one of the production liaisons told Samuelson, laughing. “Thanks to you, we had to rewrite the whole (expletive) script!” And that’s the scene we have today, filmed on the steps of our beautiful downtown train station, the only possible location for such a preposterously effective homage to the Odessa Steps sequence in Sergei Eisenstein’s “The Battleship Potemkin.”

It never really happened. It’s fiction. But you know? Who cares?

From James Southall's 2013 review of Ennio Morricone's Untouchables soundtrack, via Movie Wave:

De Palma has always believed that music has a very important role to play in a film and as such, the scores for his films tend to be striking and very much at the forefront; and he’s worked with some wonderful composers including Bernard Herrmann, Pino Donaggio, John Williams, Ryuichi Sakamoto, Danny Elfman and others. On three occasions, he worked with the great Ennio Morricone.The first of those was The Untouchables (with Casualties of War and Mission to Mars to follow in later years) and Morricone’s up-front, arresting music is quite brilliant. The score opens with “The Strength of the Righteous”, which introduces the main action theme (one of five major themes in the score), as electronic beats accompany a repeating five-note phrase heard on low-end piano and then strings, all with a wailing harmonica accompaniment. It’s a portentous opening to film and score – particularly dark yet somehow wonderfully colourful as well. Interestingly, of all the great melodic themes in the score he could choose from, when he performs the music in concert it is this dark action piece that Morricone chooses. The harmonica theme without the five-note accompanying figure is heard in the brilliant-but-brief “In the Elevator”. “The Man with the Matches” is another reprise of the material, this time filled with even more tension (and on the extended version of the album, appended with the brief “Nitti Shoots Malone”, adding a brilliant piece of anguished string writing to the end of the piece). The previously-unreleased “Courthouse Chase” is a brilliant variant on the material, on this album providing a good introduction to the familiar “On the Rooftops”, the score’s primary action cue.

“Brian De Palma is known for his serious, violent films. But Wise Guys was broad and funny for Brian. And, he wanted a broad title treatment that signaled that it was a comedy. So, graphic animation of letter shapes and silly shoot-em-up seemed suitable for the film.I started with messing with the MGM logo by spinning it into a dot that became the connection with the “I” in the titles. And, to bring a sense of humour to it with bright colour and “tough guy” red typography that was nicely punctuated by Ira Newborn’s funny, silly music” - an excerpt from Dan’s book “Hollywood Titles Designer / A Life in Film”.

Ebert: Our next movie is named Wise Guys, and this one's a real treasure. A great comedy about the Mafia that stars Joe Piscopo and Danny DeVito as a couple of very low-level New Jersey foot soldiers for the Mob. One day, they're given ten-thousand dollars of the Godfather's money to bet on a horse, and they bet on the wrong horse, because they think, "He doesn't know what horse is gonna win!" But you know what? He did know what horse was gonna win, and so they owe him two-hundred and fifty-thousand dollars, and they don't have a dime. So the Don decides their punishment, which is, he secretly assigns each one of them to kill the other one. Here's the scene earlier in the movie, one morning in the Mob-controlled restaurant where the Mafia boss is handing out the day's assignments:[Scene plays]

Ebert: [laughs at the clip just shown] That giant guy that you saw there with the horrible red or maroon sport coat is the enforcer for the Mob, and later on, the boss puts him on the case of these two guys after they've stolen his two-hundred and fifty-thousand dollars. So they are desperate. They know there's no place to turn. And so DeVito gets on the phone and pretends to be talking to his uncle in Atlantic City. An uncle who is a powerful mobster, who, if he were alive, might be able to save their lives.

[Scene plays, with DeVito pretending to talk to Uncle Mike on the phone]

Ebert: Wise Guys is a movie with one big laugh after another, and yet the thing that really holds this movie together (and you could see it there) is the genial relationship between those two guys: between Moe and Harry; between Piscopo and DeVito. They like each other and they stick together. They try to fumble their way out of this mess. And they... they're neighbors in probably the worst street in New Jersey, and they are surrounded... well, I'm sure the people that very nice people live there, but the side that they live on looks pretty bad.

Siskel: You're in trouble now, Roger.

Ebert: And they are surrounded... the people across the street are great! And they are surrounded by a movie full of some of the best character actors in the business. The big surprise for me in Wise Guys, incidentally, was Danny DeVito. I've liked him before, but he has never been better than this time, and this shows what he can do in a way that I think will be used in other movies now. Wise Guys was directed by Brian De Palma, who specializes in thrillers and crime movies, and he made Scarface, and Dressed To Kill, among his serious films. This is his first comedy in a long time, and it is a good, laugh-out-loud comedy.

Siskel: I don't even think that's strong enough-- it's a GREAT laugh-out-loud comedy, and I'm gonna have a tough time at the end of the year deciding which film I laughed out loud the longest: Down And Out In Beverly Hills, this one, or Hannah And Her Sisters. I mean, this is really a riotous film, fabulous. DeVito in a starring role-- he's not supporting people now, like in Romancing The Stone. He's absolutely terrific. There's a performance that you referred to, but I want to give credit to: the guy in the big red coat-- I think he makes this movie work just as much as the two stars-- that's played by a wrestler, a former wrestler, Captain Lou Albano. He plays The Fixer. He plays this movie at a volume pitch, that if I actually started to use it, I'd blow out every TV set that's watching us. I mean, it's a screaming performance that is hilarious. This movie, I don't know how this director Brian De Palma did it, he starts out at this level and keeps it funny and intense... it's just spectacular.

Ebert: Well, one of the things he did, I'll just repeat myself, is he fills the movie with great performances. We could go down the list and start...

Siskel: [agreeing] Oh, God.

Ebert: And the thing is, each actor is able to make his little character, or his corner of the movie, into a three-dimensional person, a presence here, so that these are people who are interacting with each other, instead of, as is so often the case in crime movies, simply stereotypes, or simply one-dimensional.

Siskel: Or vehicles for setting up a physical stunt. There aren't physical stunts here, there are people running into each other, not cars!

Ebert: That's right. there are a couple of lines in this movie, now one that... I don't want to give it, I will give it... they talk about... you mentioned that the guy's name is The Fixer?

Siskel: Right.

Ebert: That he's known as The Fixer. [laughs] They said, "What will Mrs. Fixer think?" [both are laughing] I laughed for about four minutes at that point.

On the process of color timing, etc., with the answer print

In a small darkened projection room, two men sit and watch fragments of an action movie with no soundtrack. Beaming forth from the wide-format anamorphic screen beam are powerful images of Tom Cruise, Emmanuelle Béart, Jon Voight, Kristen Scott Thomas, Emilio Esteves, Vanessa Redgrave and Jean Reno. As the actors converse, struggle, or embrace in silence, their exclusive audience exchanges a few sparse comments: “Tom’s face is a little red.” “Emmanuelle needs more blue.”The setting for this scene is Deluxe Laboratories in Los Angeles, where Stephen H. Burum, ASC is finalizing of the answer print for Mission: Impossible with timer Denny McNeill.

After months of preparation and the frenetic production itself, the answer-print stage is a time of closure for many directors of photography, a period when they can sit back and appreciate their work. Burum likens the cinematographic process to “conducting a symphony orchestra: you’re so busy bringing in the violins, doing this and doing that, that you don’t have the real joy of listening to the music, of really feeling the music. And when you're timing and you get down to the third answer print, it hits you all of a sudden: you have the time to enjoy what you did. Until then, you just don’t.”

When timing a film, the cinematographer scrutinizes the color, brightness and quality of each individual shot, gauging its coherence against the surrounding shots in the sequence. The answer print is stricken directly from the negative; its set of yellow, cyan and magenta corrections are the foundation of an interpositive from which release prints will be produced, via the internegative. By the second or third release print, the major timing adjustments have been made, so the rest is merely a matter of fine-tuning. According to Burum, skin color is the clearest indicator for refining image quality and tone at that final stage.

“When you’re timing, you want to get a reference that will serve as a standard, so that the lab can clip it out and put it next to their timing machines,” he explains. “When there are major adjustments needed, you tend to say, ‘Let’s make it a whole lot more yellow or a lot more blue.’ Later you talk about skin tone a lot because it’s harder to define; it’s a very finicky and subtle hue.”

"De Palma left and right" -- On the collaborative working relationship between Burum and De Palma:

The feature film version is directed by Brian De Palma, whose relationship with Burum is well established.Over the past 12 years, the two filmmakers have collaborated on five previous features: Body Double, The Untouchables, Casualties of War, Raising Cain and Carlito’s Way. Both men share an encyclopedic knowledge of cinema and a passionate enthusiasm for filmmaking. The lengthy collaboration between the duo seems a natural one, as a keen appreciation of film history informs the work of both.

De Palma is best described as a postmodern director; his films are full of references to past directors such as Eisenstein, Hitchcock and Antonioni. He knows every storytelling trick in the book, and doesn't hesitate to use them. It is telling that Quentin Tarantino cites Blow Out (shot by Vilmos Zsigmond, ASC) as his favorite film, for in many ways, the young auteur is DePalma’s heir. Critics sometimes lambast the director as a mere maker of showy homages, yet, like Tarantino, he infuses his references to past films with a very contemporary irony that creates a personal vision.

In a very different way, Burum has used his own love of the classic Hollywood tradition to enrich recent American cinematography. A master stylist, Burum has on several occasions assimilated the aesthetics of bygone genres and transformed them into original and modern imagery. Witness the highly stylized rendering of detective serials in The Shadow, or the brilliant melange of film noir and comedy in The War of the Roses. Burum's distinguished career spans from the stunning second-unit cinematography on Apocalypse Now to his masterful, Academy Award-nominated work on Hoffa. In addition, he has received ASC Award nominations for both The War of the Roses and The Untouchables, winning for Hoffa.

After working with De Palma on so many pictures, Burum says that he and the director speak in shorthand on the set. “I love working with Brian. He’s the greatest; he knows exactly what he’s doing. There’s not much dialogue between us on the set. [The collaboration] is not artsy at all, but very matter-of-fact. I have an expression that I use: ‘De Palma left and right.’ If Brian says the frame ends at a certain point, it’s going to end there. There is no reason to shoot anything past that point.” Burum also understands De Palma on a personal level. To an outsider, he says, “Brian may seem gruff, but he keeps all of his feelings inside.” The cameraman realized this during the shooting of Al Pacino’s death scene in Carlito’s Way, when he saw the director “with tears in his eyes.”

On working with production designer Norman Reynolds, and evoking three moods, "old Europe, America, and new Europe" --

Like an IMF mission, the production of the film was a race against time, shooting on location in Prague and London, and on sets built within the vast Pinewood Studios soundstages. However, the film's British production designer, Norman Reynolds, notes that the film's European locales merely enhance its essential spirit. "Mission: Impossible is an American action film, in the best sense of the term," he says.Reynolds, who earned two Oscars for his memorable design work on Star Wars and Raiders of the Lost Ark, is well-positioned to comment on the relationship between the production designer and the cinematographer. “The designer [helps to set] the picture's tone in visual terms. Now that's apart from the cameraman, who obviously has the ultimate control in that area, because he can make it dark, light, colored or whatever. So what we designers do is very much in the hands of cameramen. I certainly stay in touch with the cameraman as much as I possibly can.

“While we were in Prague, Steve was obviously very involved in location scouting and preparing things, so there were times when he and I were separated. But when we moved to the studio, I involved Steve as much as possible in the set design. It was quite selfish really, because the easier I made Steve's job, the better the film was going to look. We liked working together, and that's really the name of the game."

In planning their visual design, Burum and Reynolds referred solely to the script and not at all to the television series. In fact, Burum confesses to having never really watched the TV show. "I remember a little from college, but I never got a chance to see an entire episode," he admits.

Following the natural divisions of the script, Burum created a different lighting approach for the missions in Prague, Virginia, and on the TGV train, producing a visual diversity and rhythm that enriches the film. The cinematographer summarizes the three moods he sought to evoke as "old Europe, America and new Europe."

In Prague, Burum sought to create an atmosphere that evoked "the old European spymaster stuff. You know, the spymaster slinking around, dining in chic restaurants, smoking cigars and drinking brandy, while some Eurasian woman is wearing a tight silk dress with a mink dropping off her shoulder, with a Twenties bob hairdo — the Mata Hari thing. Here you are in Prague, which has just been freed from the Communists and is still mysterious, almost Oriental. Anything can happen, and of course, all kinds of nefarious devious stuff is going on because everyone is grappling for power, and everything is up for grabs."

In lieu of Mata Hari, Mission: Impossible features French actress Emmanuelle Béart as Claire, an IMF member and romantic interest of Hunt’s. To give Béart a "more ethereal" appearance, Burum chose his customary black silk stocking diffusion when shooting her close-ups. Onscreen, the diffusion is subtle and Béart's face still looks sharp. The cinematographer explains that "women, even when heavily diffused, don't appear diffused on film because their makeup accents their eyebrows, eyelashes and lips, which gives you a false sense of sharpness. For example, normal lip color blends in with the face but, with lipstick and liner, the lips look a lot sharper than they really are."

Most of the "old Europe" sequences in Prague take place at night. From the look of the film, the crew had the run of the Czech capital. The venerable but run-down Natural History Museum posed as the embassy's reception hall. Key exteriors were shot in Prague's two prime tourist spots: the beautiful square at the center of the old town and the famous Charles Bridge. These picturesque nightscapes required an excessive amount of light, since Mission was shot in the anamorphic format. For Burum, the lens T-stop setting is an essential factor in the quality of widescreen images.

"Many people ask me why my anamorphic shows look so sharp. It's because I know which stop to put the lenses at. You can't get an anamorphic lens below T4 and keep it sharp. In desperate situations, I have shot scenes at T2.8. I've been able to get away with it because I light very hard and very contrasty, which gives the images a phony sharpness. But if you try to light an anamorphic image at T2.8 with a soft light, the image will have no snap." Rawdon Hayne, Burum's 1st camera assistant, was instrumental in this endeavor.

Burum used Panavision's C-series anamorphic lenses, which he prefers to the E series because of their small size. "There's something about the older lens design that gives the appearance of a bit more depth of field. In point of fact, the term depth of field is baloney; there is only one point of absolute focus. Everything in front and everything behind is not really in focus, but rather seems to be in focus to your eye. If you have a lens that is ultra-sharp or heavily contrasted, then you see that difference in focus immediately. Older lenses are not quite as sharp, so they only appear to have more depth of field."

Read Burum detail much more in the article regarding lenses, lighting, old-fashioned process shots, etc., at American Cinematographer. One curious image included there is this one:

Apparently taken from the original magazine article, the image above includes the following caption:

Luther (Ving Rhames) on the train, sharing a frame with an unfocused Max (Vanessa Redgrave). Here, Burum accentuates the space between the characters, as Luther is undercover, secretly trailing Max.