MANY DETAILS IN EPISODE #49 OF "WHEN GEN-X RULED THE MULTIPLEX"

Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | April 2021 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

| 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 |

| 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | |

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

With her role in the new short film Koreatown Ghost Story, Margaret Cho is interviewed by Fangoria's Meredith Borders, who gets the comedian/actress talking about her favorite horror films:

Once we started talking about the genre in general, Cho really opened up. Although, as she says, it’s always been what she watches most, she’s been especially diving in during the pandemic, and one South Korean television series stands out in this deeply weird time we find ourselves:“Most recent, I would say that I really love Sweet Home, which is almost a K-drama of horror, but it’s the definition of post-apocalyptic – it elicits some emotions about the pandemic, too. There's the paranoia of other people, there's this thing that's outside that you don't understand what's happening. There's a lot of monsters that are taking different forms that could be like variants. It’s really scary, but it's also the classic horror story where the protagonist finds his strength within, which is really what horror is about. You want to see somebody dig deep and into their heart and survive this nightmare, and the best horror does that.”

When we got into her favorites – a challenging question for any horror fan – she had a lot of answers: “ghosty” movies, found footage, body horror, Halloween and the “entire series” of Friday the 13th. “I love horror with kids, because kids freak me out.” She listed lots of Asian horror films: The Untold Story, Ju-On, Ringu, the original Dark Water – “which ultimately became a true story with Elisa Lam.” Like the truest of genre purists, she adores a lot of pre-‘70s titles: Séance on a Wet Afternoon, The Haunting, anything Hammer or giallo. But when it comes to her absolute favorite, she avers that’d probably have to be Brian De Palma’s Carrie, although she acknowledges that what’s most special about Carrie transcends genre.

“Carrie is kind of everything, but what it really is, is this person – that's been victimized by all these people – finding her strength, but then Carrie becomes an antihero, too. So it’s really important to me.”

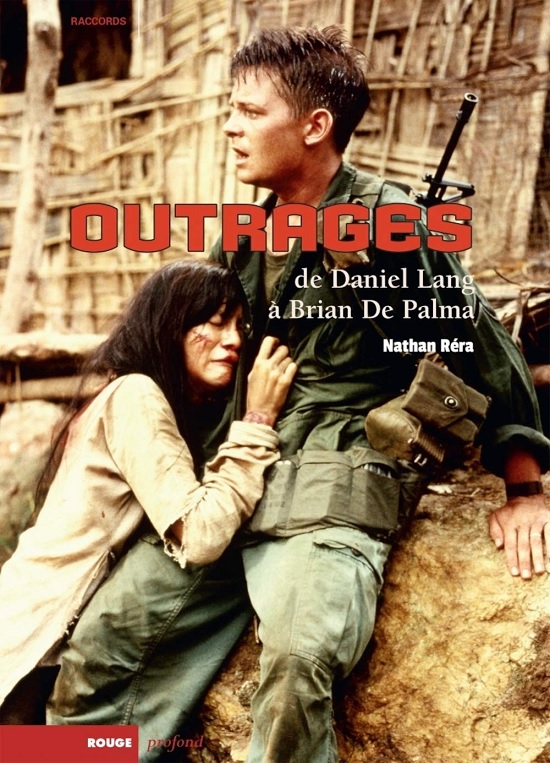

Adapted from an investigation by Daniel Lang published in the New Yorker in 1969, Outrages (Casualties of War), Brian De Palma's nineteenth feature film, chronicles the kidnapping, rape and murder of a Vietnamese woman by a patrol of American soldiers led by Sergeant Meserve (Sean Penn). First Class Eriksson (Michael J. Fox) refuses to participate and sets out to expose the culprits.Nathan Réra's book reconstructs the pitiful history that led to the creation of this underestimated masterpiece. From numerous rare documents (military archives, correspondence, unpublished scenarios), the author returns to the real facts and their revelation in the American press, then on to the adaptation projects which followed one another during a decade, before immersing the reader in the heart of De Palma's film creation.

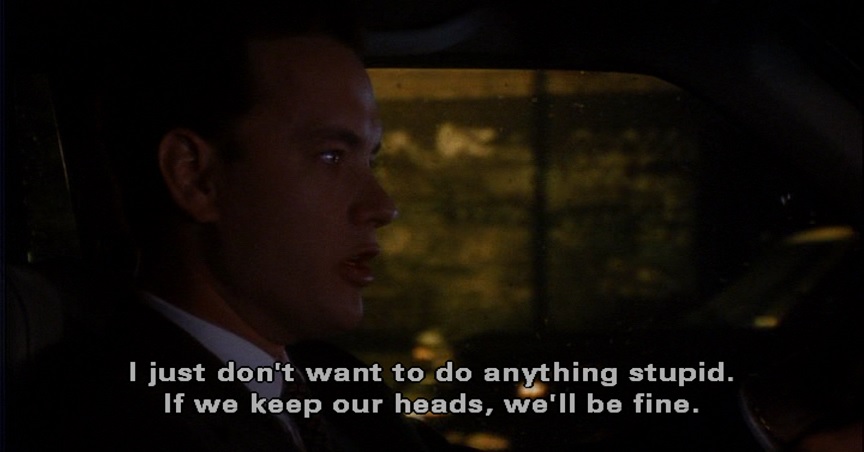

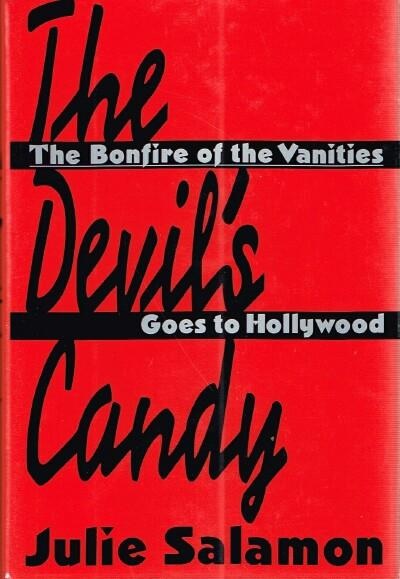

To some, De Palma was not the obvious film-maker for this material. He had previously made gruesome works such as Dressed to Kill, Scarface and Carrie, and Bonfire did not seem like a natural fit. But after suffering a major financial blow from the failure of his previous film, the Vietnam war drama Casualties of War, De Palma needed a hit. And after the success of Wolfe’s novel, the film seemed to be a guaranteed money-maker.A big problem for the studio was that the novel lacked any sort of likable or sympathetic character. Wolfe’s book was deliberately cynical, examining the various institutions of New York with disdain. If there was one actor that didn’t appear to have an ounce of cynicism, it was Tom Hanks. And so the producers decided to do the unthinkable. They tried to make Sherman McCoy a likable protagonist, and gave the role to Hanks. Equally odd was the casting of Bruce Willis as Fallow. Willis, fresh from the success of Die Hard, wanted to diversify his career away from charismatic action heroes. Yet Fallow is written as a sleazy, scrawny Brit, a far cry from the chiselled all-American handsomeness of John McClane.

De Palma then did something that, in retrospect, would ensure the film’s notoriety – he allowed Salamon to document the film. Having worked as a financial reporter, Salamon had become the Wall Street Journal’s film critic in 1983. She had got to know De Palma and became friendly with him. “He was a kind of troublemaker, and he would plant me story ideas,” she remembers.

Though the crew were mostly aware of her on set, the studio didn’t know about Salamon until five months into production. When Salamon started asking difficult questions of Eric Schwab (Bonfire’s second unit director), he confronted De Palma; Schwab says De Palma told him to be honest. “He said to me: ‘This is going to be an honestly brutal thing of what you go through when you’re making a film, just tell her everything.’”

Salamon’s description of the film’s progress was unsparing. Production began in April 1990 and there was trouble from the beginning. The studio was worried that for a novel about racial politics, there is hardly one sympathetic black character. The studio told De Palma that the character of Judge Kovitsky had to be black instead of Jewish. (The judge was renamed White.) The concerns about racial representation even affected filming in the Bronx. Assistant director Chris Soldo remembered a local “somehow got through a perimeter and got right up to Brian De Palma’s face and started berating him for not having more black people represented on the crew”. (Soldo adds: “Probably a fair critique.”) Eggs and lightbulbs were thrown at the production from Bronx tenement rooftops.

There were further complications with the cast, as recorded by Salamon. As the production moved from New York to Los Angeles, Melanie Griffith got breast implants, a potential continuity nightmare. Hanks was a popular presence on the set, but Willis less so. At one stage, Salamon relates that he publicly challenged De Palma’s directorial authority, instructing his fellow actors how to play scenes. He also had a special assistant on hand to cover up his nascent bald spot with makeup, and asked De Palma to backlight him rather than wear a wig.

Despite the difficulties, once filming was over, everyone was convinced they had a hit on their hands, including the studio. Salamon recollected in The Devil’s Candy that one Warner Bros executive declared it as “the best movie we’ve ever made”. However, test screenings showed that the film wasn’t working with audiences and re-edits were made, including a change to the ending in which McCoy and Fallow have a swordfight. Despite the changes, Bonfire only made $15m at the US box office, well below its $47m budget.

The critics hated it. The Los Angeles Times called it “calamitous” and an “overstated, cartooned film for dullards”. The New York Times’ verdict was “gross” and “unfunny”. Rolling Stone thought it “achieves a consistency of ineptitude rare even in this era of over-inflated cinematic air bags”. Much of the critics’ ire was directed at the casting of Hanks and Willis. Schwab thinks that the negative response towards Hanks in particular was not simply because he was not Wolfe’s idea of Sherman McCoy. “Whenever I saw any reviews, I basically felt well, he is good in this role, even though you can’t accept it,” he says.

All of this came as a surprise. Salamon remembers that, despite the occasional tensions during production, no one ever thought the film was going to get the critical and commercial lambasting that it did.

Nor do Salamon or the crew I spoke to look back at the movie with bad memories. What became a notorious flopdoes not seem to have left any lingering resentment. It certainly didn’t ruin any careers, with Hanks and Willis going on to hit after hit in the succeeding years.

As for De Palma, he bounced back with successes like Carlito’s Way and Mission Impossible but never found Bonfire’s reception justified. In an 1992 interview with Charlie Rose, De Palma said: “You don’t think you have made a bad movie. I will say to this day, the way I made it is an interesting movie that I like. It is not Tom Wolfe’s Bonfire of the Vanities. The problem is that everyone that wrote about the movie, read the book.”

Soldo, for one, looks back on the experience if working with De Palma with fondness, saying that “there was a tremendous loyalty and a maintenance of a relationship between movies … if you were lucky enough to be one of those people, you got to participate in some really interesting and good work”. He adds: “De Palma’s always been kind of fearless about or seemingly immune to what people think about him or say about him.”

Salamon’s book was published in 1992, and, unlike the film, it was critically acclaimed and became a bestseller. However, she says it affected her ability to work as a critic; her stint in the post ended in 1994. “For me personally, writing about Bonfire really was the beginning of the end of my career as a film critic, because after … spending the time, day in and day out for almost a year watching this process, I found it harder and harder to write negative film reviews.

“I didn’t know it was going to end up becoming this huge, quote, unquote, flop that people were going to peg all the negative attributes of Hollywood film-making, I think unfairly, on its back. My favourite reviews of my book were the ones that said this isn’t a book about a big flop. This is a book about people who love their craft, who love their work, and were trying to do something great.”

Not only that, but Vorisek worked on De Palma's Blow Out (1981), as well as Dressed To Kill (1980). Having worked with De Palma since Sisters in 1973, and then through Carrie (1976) and The Fury (1978), one wonders if Vorisek might possibly be the sound person who De Palma asked, during Dressed To Kill, to get some new sounds, thus sparking the idea that sets off Blow Out. Vorisek worked one more time with De Palma, on The Untouchables in 1987, which was written by David Mamet. Vorisek's final film was Mamet's excellent directorial debut, House Of Games, from that same year. He died two years later, in 1989.

The Los Angeles Times' Randall Roberts states that by 1974, "TONTO had become a circuitous beast that included machines made by Moog, ARP, Oberheim, Roland and Yamaha; drum controllers, sequencers and, later, MIDI converters; and thick gauge wire procured from surplus supplies made for the Apollo mission and Boeing 747 manufacturing. Those familiar with Brian De Palma’s cult classic film Phantom of the Paradise have seen TONTO in action. It provides the setting for a wild scene in which protagonist Winslow Leach, donning a silver owl’s mask, performs a surreally ridiculous song on the contraption."

Roberts mentions that "Cecil was said to be furious at TONTO’s unauthorized appearance in the film." Indeed, Cecil talked about this a bit in a 2017 feature article for Music Works, written by Jesse Locke:

The pair’s invention and ambition led to an intense four-year collaboration with Stevie Wonder. The legendary artist wrote nearly 150 songs before the tracks were selected and released on his groundbreaking albums Music of My Mind, Talking Book, Innervisions, and Fulfillingness’ First Finale. During this time, TONTO was expanded to include two Moogs, two ARP 2600s, four Oberheim SEMs, modules from EMS, Roland, and Yamaha, drum controllers, sequencers, and MIDI converters, all fused together with Boeing 747 airplane wire. Jim Storyk constructed the woodwork at Electric Ladyland, studied geodesic domes with Buckminster Fuller, and then designed TONTO’s singular cabinets. Its primitive prototypes were replaced by synths rolled out on a tea trolley or a gurney, and its six-foot curves were ergonomically tailored to match Cecil and Margouleff’s heights. In a 1984 Keyboard magazine article (later adapted for the 2011 anthology Synth Gods), writer John Diliberto points to the influence of their electronic Afrofuturism. “This collaboration changed the perspectives of black pop music as much as The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper altered the concept of white rock.”While Wonder’s TONTO era resulted in Grammy awards, lucrative tours, and massive sales for Motown Records, Cecil claims he “never made a penny from the royalties.” Cecil bought out Margouleff in 1975 and forged a new partnership with the poet, musician, and activist Gil Scott-Heron. At the height of another fruitful period, TONTO appeared on the cover of Scott-Heron’s album 1980, which featured synth-powered songs about nuclear protests and the hardships of illegal Mexican immigrants.

TONTO went on to help shape hit releases from Minnie Riperton, the Isley Brothers, the Doobie Brothers, and countless other artists. It famously lived briefly in the studio of Devo’s Mark Mothersbaugh in the mid 1990s, and was immortalized in a parody in The Simpsons. Its best-known visual appearance, in Brian DePalma’s cult film Phantom of the Paradise, allegedly occurred against Cecil’s will.

“TONTO was at the Record Plant in Los Angeles when we were working there with Stevie,” he recounts. “During that two-year period, the studio rented the room to the film and told them they could use TONTO as a prop. No one said a word to us. When I walked into the studio and saw they were filming it, I blew a gasket!

“We eventually negotiated that they could use the footage if they paid us for the visual rights,” he continues. “The other part of the deal was that whenever TONTO appeared on screen the music was supposed to be played by the real instrument. Of course it ended up being Paul Williams’ piano instead. I’ve seen the movie a few times and it always [used to make] my blood boil. [But] I learned to let it go long ago.”