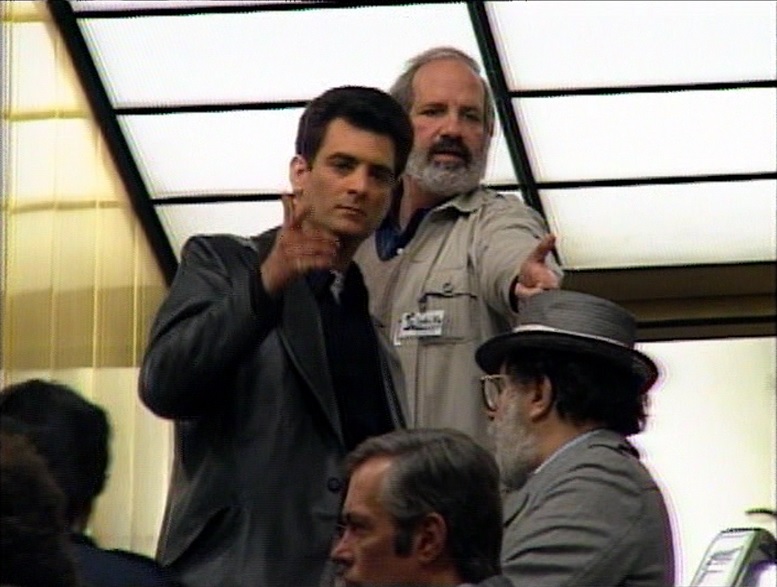

's film, and the real-life events that it is based on. In the article, Réra reveals that he interviewed De Palma,

, and more for the book. In the introduction to the article, the Gone Hollywood editors state that Réra is a "lecturer in the history of contemporary art at the University of Poitiers, who offers a fascinating backward inquiry into the film and the 'news item' from which it is inspired." Here is a Google-assisted translation of Réra's post:

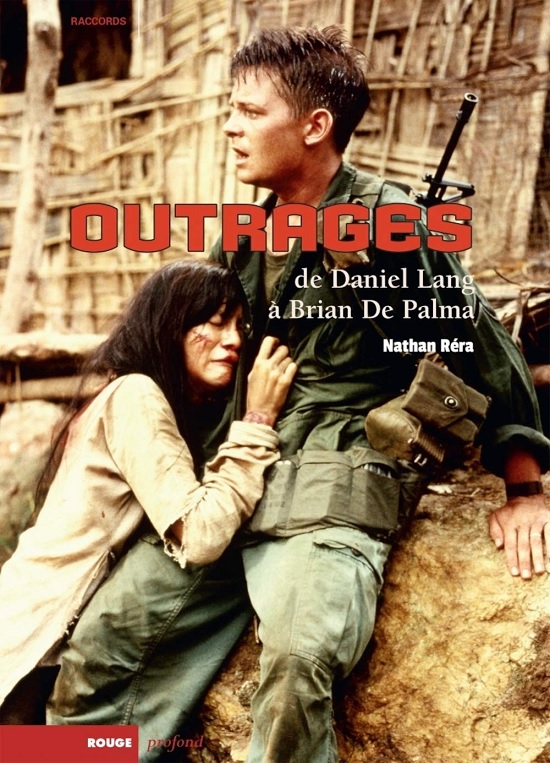

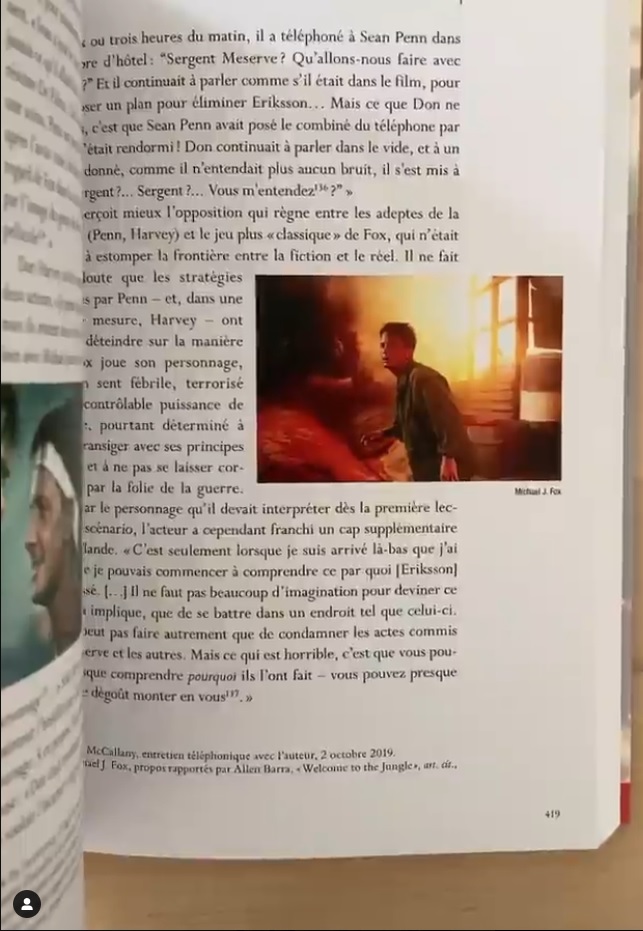

STORY OF AN OBSESSION I have vivid memories of my discovery of Outrages at the end of my adolescence: I can still see myself buying the very first edition of the film on DVD, to expand my collection of works by De Palma… We were then at the very beginning from the 2000s. I was intrigued by this film, of which I only knew a few images; I assumed that it must be in line with the “great” films on the Vietnam War, alongside Apocalypse Now, The Deer Hunter, Platoon or Full Metal Jacket, films that I had seen during my adolescence and which had marked me, each in their own way. However, watching De Palma's film awakened feelings in me that I had never experienced in any other war film. I came away deeply shaken. I quickly realized that Outrages was not just another war film - nor was it completely a film about Vietnam ... - but a film about rape as a weapon of war. The impact the feature film had on me owes a lot to the heartbreaking renditions of Thuy Thu Le and Michael J. Fox, the terrifying performances of Sean Penn and Don Harvey, the chiseled writing of David Rabe as well as the overwhelming music of Ennio Morricone (in my eyes, perhaps his most beautiful score…). Since that first viewing, Outrages has not let go of me; I have seen it many times. Between the young film buff that I was when I discovered it and the confirmed researcher that I have become, a specialist in visual representations of mass violence and genocide, I have obviously come a long way. For example, a film like Schindler's List, which sparked my interest in depictions of the destruction of European Jews, confronted me with aesthetic, ethical and moral issues of the highest order; so much so that today my take on this film, from a filmmaker whom I admire by the way, is much more nuanced than it was twenty years ago. Quite the opposite of Outrages: with each viewing, the impression of strength and accuracy exuded by Brian De Palma's film remains intact.

I wanted to study the film to try to understand why it obsessed me so much, a bit like Eriksson who cannot forget the face of Oanh. This research was initially a personal, intimate quest. Originally, my plan was to write a book focusing exclusively on De Palma's film, which would have retraced its history, from its genesis to its theatrical release. To that end, I first contacted the filmmaker and screenwriter, David Rabe, to find out if they would be willing to speak with me. They both answered yes. It took several months for a meeting with De Palma to take place; on the other hand, I very quickly started a long correspondence with David Rabe. Our discussions convinced me of the interest of giving the floor to all those who had participated in the film, not just the most illustrious… Of course, I knew that De Palma's film was based on a text by the American journalist Daniel Lang originally published in the New Yorker. I had acquired the excellent French translation published by Editions Allia in 2018, but I was eager to know more about the fabric of the report and the journalist's intentions. The investigation into De Palma's film was then coupled with an investigation into Lang's work, which I was able to carry out with the agreement of his daughters, who allowed me to have access to his archives. . At the same time, I got my hands on the archives of the court martial trials; I was able to locate several funds relating to the early adaptation projects of Casualties of War, well before that of De Palma; and I also spoke with Michael Verhoeven, the author of o. k., the first film inspired by Lang's investigation, known to have prematurely interrupted the Berlin International Film Festival in 1970. My research thus took on a scale that I was far from suspecting at first! I am summarizing here in a few lines nearly three years of intensive work, punctuated by periods of doubts, false leads, trial and error ... I sometimes had the impression of throwing bottles into the sea! But my persistence paid off. It was essential to stir broad in order to reconstruct the history of Casualties of War over the long term, from 1966 (date of the real events) to 1989 (date of release of De Palma's feature film).

CASUALTIES OF WAR BEFORE OUTRAGES

Several parameters made possible the realization of Outrages, which Warner had started in 1970 without succeeding in completing the project. De Palma reactivated the project in the wake of the release of The Untouchables (in 1987), which was at the time his greatest commercial success; the collaboration with its producer, Art Linson, was in good shape. When the latter asks him which project he now wishes to work on, De Palma sends him Lang's text, which he had dreamed of bringing to the screen since 1969. He had also tried to carry it out in 1979-1980, in a time when he was already working with David Rabe on a project called Prince of the City (which Sidney Lumet would eventually direct). Coincidence: Rabe, too, had been dreaming of writing an adaptation of Casualties of War for the big screen for several years! The screenwriter approached Lang at the time, shortly before the journalist's death, but negotiations did not go very far, and De Palma eventually embarked on the directing of Dressed To Kill. Seven or eight years later, the situation has changed: after the success of The Untouchables, De Palma has the big studios at his feet and can afford the luxury of choosing his projects. However, it should be remembered that the choice to adapt Casualties of War was perilous: the war in Vietnam remained at the time a sensitive subject, on both political and moral levels, despite the great cinematic successes that followed one another throughout the decade ... It is for this reason that Paramount, which was initially supposed to produce the film, finally threw in the towel, before Columbia decided to grant it its "green light".

Outrages is a film adaptation of a journalistic investigation, which is itself based on the hundreds of pages of court martial transcripts Lang had viewed. David Rabe and Brian De Palma therefore necessarily made cuts, simplifications or adjustments. Some of their narrative choices conflict with the vision of Daniel Lang, who was heavily involved in the various adaptation projects prior to Outrages. However, Rabe's script is broadly faithful to Lang's text, as it is to the real story. The portrait he paints of soldier Eriksson is very close to the sensitive one painted by the journalist, and the unfolding of the facts resumes that of the book, even if the first part of the film, which relates the daily life of the soldiers in Vietnam, extrapolates the testimony of the real Eriksson. Everything is plausible, however, and we must insist on the realism of the feature film, which is due to the vision of Rabe (himself a Vietnam veteran) as much as to the work of historical or military advisers. There are of course some differences between reality and its cinematographic transposition. The main one relates to the nature of the crime: in reality, it was a planned feminicide. From the start of the mission, it was agreed that the soldiers would abduct the young woman, Phan Thi Mao, to satisfy their sexual urges, and then kill her. In the film, the kidnapping and the rape are well planned, but the murder is decided in haste, when Meserve (Sean Penn) becomes concerned that the captive will be spotted by the American helicopters which fly over the area where he and his men lie. In my book, I analyze these different gaps between reality and film; it was necessary not to obscure them, as they reveal the tensions inherent in the work of adaptation.

RAPE OF WAR VS. FEMINICIDE

Outrages is evidently at the heart of the great DePalmian oeuvre, because it contains figures and themes dear to the filmmaker; but at the same time it constitutes a kind of outgrowth of it, forming part of a small nucleus of films (with Greetings and Redacted) which tackle war, male domination and violence against women. On the directing side, the film has a few brave moments that bring to mind De Palma's taste for complex camera movements (especially the tunnel sequence, at the start of the film). However, one feels the director less concerned with visual performance than in his other films; he seeks throughout the story to adapt the form to his subject. From this point of view, his use of Steadicam is particularly interesting, because the movements performed with the device are not aimed at gratuitous virtuosity: they take care of the moral questions raised by the narrative. Among the passages that arouse in me a renewed emotion each time is the metro scene, which frames the film. This almost silent sequence, carried by the music of Morricone, gives an account of Eriksson's break-up, of his inability to stay in the present, in the world of the living, to simply relive without thinking of the one he couldn't save. It seems like the ending leaves us on a "positive" note, but studying the multiple layers of scriptwriting reveals how reductive that feeling is, and does not do justice to Rabe's intentions. Eriksson’s last look is unforgettable… I could also cite the sequence of the kidnapping of Oanh, of unbearable violence, and the rape itself, which De Palma films with remarkable ethics. More broadly, I find Thuy Thu Le's bodywork gripping. Rarely has an actress portrayed a rape victim so realistically; the passage where Eriksson tries to establish a dialogue with Oanh, while her body is ravaged by multiple wounds and bruises, does not leave the spectator unscathed.

De Palma has often said that the reception of his film in the United States has been abysmal. It seems to me that this impression needs to be qualified a little: by going through the archives of the American press of the time, we also find good (even very good) reviews, not only that of Pauline Kael in the New Yorker! But it is true that many others have distinguished themselves by their great violence. The most striking is undoubtedly that of Frances FitzGerald, who won the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award in 1973 for a book on Vietnam. In the magazine Village Voice, she attacked De Palma, reproaching him for having made a "sado-porn" film and denouncing the supposed improbabilities of the story ... She had obviously not read Lang's book! Veterans associations have also stepped up to denounce the portrayal of the US military, claiming that the facts recounted in the film were "exceptions." I believe the reception of the film in the United States is indicative of the depth of the moral wound that the Vietnam War has caused in American society. Of course, Platoon had achieved resounding success two years earlier; but Stone's film was by no means as critical as De Palma's film. The reception of Outrages also reflects, in retrospect, how war rape and femicide were viewed at the time. That part of the criticism, supported by the veterans' associations, could deplore the image that the feature gave of the American army seems, in today's society, quite improbable ... While the real subject of the film was at the same time very largely brushed aside! In France, the film also had its detractors, but overall the critics were much more receptive, with excellent analytical articles published by Laurent Vachaud and Antoine de Baecque, among others, in Positif and Les Cahiers du cinéma.

WHY REVISITING OUTRAGES IS NECESSARY

De Palma never really recovered from the critical failure of Outrages. Of course he returned to success afterwards, but he never took in the reception that was given to this film, which he rightly considers to be his most personal work. Some of his collaborators, whom he reunited with for his next film (The Bonfire of Vanities), told me that De Palma is not a filmmaker who dwells on failures; he never poured himself out with them. His reaction, after the film's screening at the Cinémathèque française in 2018, however, proves that Outrages is particularly close to his heart. It is not trivial to let such emotion shine through when you talk about a film made thirty years earlier! In 2006, De Palma directed Redacted, which is the tracing of the story of Outrages in the context of the Iraq War; a film once again based on a true story. Among his recent projects, there is also a film inspired by the Weinstein affair ... But I believe that on closer examination, the problem of violence against women and male domination haunts all of De Palma's work.

Revisiting Outrages is more necessary than ever, for at least three reasons. First of all, because it is a great film, still too little known, with complex issues, one of Brian De Palma's most successful works, and undoubtedly the film that best crystallized the moral bankruptcy of America in Vietnam. Secondly, because rape as a weapon of war is a subject that is still too little talked about, despite the existence of remarkable work by historians and journalists. Finally, because we must fight this culture of rape which plagues our societies. We feel that things are evolving, with the liberation of speech movements, but there is still a long way to go to educate the conscience, and especially those of men. Outrages speaks of rape committed in wartime, in a context where all moral barriers are collapsing; but it also speaks of the constitution of a culture of rape, which flourishes well upstream, through homosocial rituals. Outrages is also the antithesis of films which trivialize rape, or which make it a spectacle. Rape is represented here as an experience of great violence, from which one cannot recover; neither the one who is the victim, nor the one who is the witness. I believe that this film - like the book by Daniel Lang - can help educate the conscience and the gaze, because it raises the decisive question of individual responsibility. Positioning yourself on the good (or the bad) side is not inevitable: it is a choice.