"I REALLY LIKE THIS CAT-AND-MOUSE GAME, IT'S FUN TO WATCH"

Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | July 2021 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

| 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 |

| 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 |

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

As Disney grows bigger and acquires more properties, there are countless ways for the company to dominate the box office in any given year: a new Star Wars movie, another entry in the Marvel Cinematic Universe, the latest tear-jerking Pixar project, even the long-awaited sequels to James Cameron’s Avatar. Such domination has come at the expense of projects that feel fresh and marginally original—these days, almost everything Mouse House churns out is a sequel, reboot, remake, or an extension of an established cinematic universe. (Even a studio as lauded as Pixar got a little too sequel-happy for its own good before Onward, Soul, and Luca.) But the box-office receipts speak for themselves, and as Disney doubles down on its strategy of maxing out its IP, the company is returning to an unsung resource: theme park rides.Considering the studio is so risk-averse, it’s oddly amusing that theme park movie adaptations have repeatedly come out of the Disney pipeline—it’s a gambit that’s almost always failed. A middling made-for-TV adaptation of Tower of Terror got the ball rolling in 1997, but it wasn’t until the turn of the century that Mouse House started really swinging for the fences: If there’s one thing Mission to Mars (2000), The Country Bears (2002), and The Haunted Mansion (2003) have in common, it’s that their sheer WTF-ness was almost instantly met with quizzical responses. Mission to Mars is perhaps the most notable outlier and was directed by the great Brian De Palma (an auteur who’s as un-Disney as they come); it was based on a ride that was already closed and featured legitimately disturbing death scenes despite being rated PG. (This is also why Mission to Mars unironically rules, scathing reviews be damned.)

The latest in the Disney theme park movie canon, Jungle Cruise, arrives on Friday, and it’s probably not the most encouraging sign that some insiders are already bracing for a less-than-stellar financial return. But Jungle Cruise isn’t so much trying to capture the spirit of the eponymous Disney ride—given that it was recently revamped because of racist caricatures, that’s for the best—as it is trying to ape the multibillion-dollar success story of theme park ride moviemaking: the Pirates of the Caribbean franchise.

When the first Pirates of the Caribbean movie, The Curse of the Black Pearl, was released in 2003, the whole idea of turning an amusement park ride into a blockbuster was ridiculous—especially given Disney’s previous failures in the space. But The Curse of the Black Pearl was a legitimate hit and a swashbuckling adventure so universally admired that Johnny Depp even landed an Oscar nomination. (When you think of performances that get on the Oscars’ radar, Captain Jack Sparrow hardly comes to mind.) The Curse of the Black Pearl was the fourth-highest-grossing movie of the year, and a sequel was inevitable.

Director Gore Verbinski ended up shooting back-to-back sequels, Dead Man’s Chest and At World’s End, to complete a trilogy that broadened the franchise’s fantastical pirate universe—one where, to paraphrase Captain Barbossa, the audience best start believin’ in ghost stories.

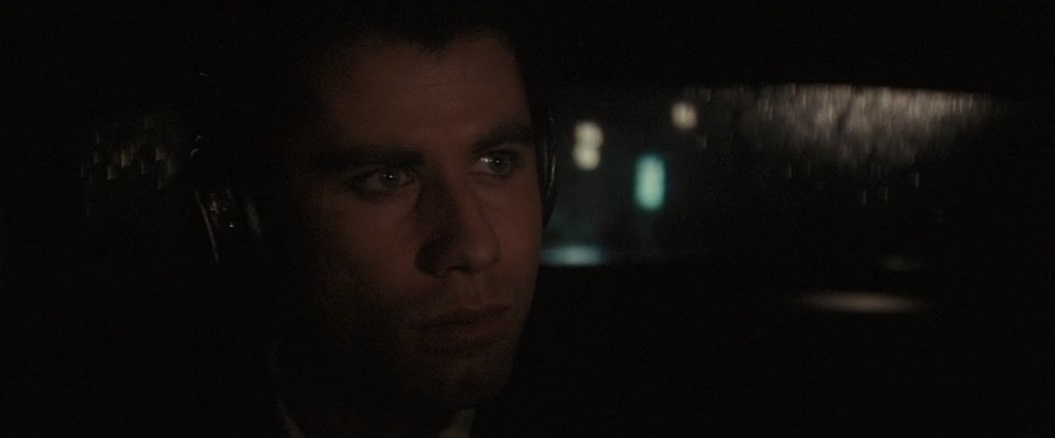

Blow Out is a movie full of contradictions, not unlike conspiracy theories, which actually manage to strengthen the text. The movie contains contrasting tones that compete against each other for supremacy. Blow Out notably begins with its careful exploitation of the audience. The masterful opening POV sequence occasionally has a moody “killer theme” that turns up on the soundtrack during the slasher’s violent acts, which increasingly overpowers the playful party music playing in the dorm unsuspecting students inside have no idea that they’re in danger. Just like how the music does this, the visuals also create this odd dissonance as the audience tries to figure out what’s going on until they finally realize that this introduction is a ruse and part of the artifice that’s inside of Blow Out, rather than Blow Out itself. It’s the first scene in the movie and also the first time in the film that the audience is forced to reckon with this while Blow Out continually toys with what is reality, what is art, and where the two overlap.It’s all a lie.

To go one step deeper, Garrett Brown, the creator of the Steadicam, was well-practiced with the equipment after his work on The Shining, but this piece in Blow Out is intentionally clumsy because it’s supposed to resemble a low-budget horror movie. It wants to mess with the audience and use the quality of the camerawork to become the first clue that this is actually a movie within the movie. Garrett actually laments that he couldn’t shoot the opening POV sequence properly and was forced to make it look so schlocky, but that’s the magic of this De Palma introduction. It achieves a more technologically advanced and psychologically enriching version of Halloween’s legendary opening sequence and Blow Out’s introduction genuinely helped popularize the use of the Steadicam and showcase its versatility as a filmmaking tool. It’s a sublime pairing between Garrett Brown during the infancy of the Steadicam’s development and Vilmos Zsigmond’s ever-growing talents as a cinematographer.

This illusory artifice that kicks off the movie also bookends Blow Out. Another powerful example of the blurred lines between art and reality is what concludes Jack and Sally’s story. Burke’s assassination plan that takes out Sally is intself based around subterfuge and fabricated panic that’s exactly the type of scheme that conspiracy theorists would develop. On a deeper level, Sally’s screams of terror fail to be heard and she’s unable to receive help because displays of riotous Americana literally drown her out; whether it’s the noise of the fireworks, the public cheering, or the celebratory music. Her corpse basks in the glow of red, white, and blue lights.

The one time that Jack needs to hear Sally’s scream, he can’t, and it’s what costs her her life. It’s devastating, but even harsher of a blow because of Jack’s aural life and how important listening is to him. It’s a horrifying reality about how the dangers of patriotism can strangle America and bury what’s important, which is relevant then, but even more frightening now with how the news and social media can filter out what doesn’t fit their narrative and highlight America’s benign successes. Pro-America messages can overpower what’s really important and strangle the cries for help in a figurative sense, just like Blow Out literally does, and it was made forty years ago.

Brian De Palma gets so many good and chilling performances out of John Lithgow, but his villain in Blow Out, the mysterious Burke (who’s based on G. Gordon Liddy to some degree), is seriously some of the actor’s strongest work. Burke’s appearances here are incredibly brief, but Lithgow makes every second count. Lithgow’s performance as Burke is also a fantastic example of how the weight and intensity behind a villain can mount through their actions, even when they’re not physically being seen on the screen, so that when they finally do show up it’s deeply cathartic. It becomes the satisfying culmination of all of these sinister machinations up until this point. The camera moves with precision during Burke’s calculated murders in contrast to the klutzy maneuvers from “Co-Ed Frenzy.” De Palma uses the language of this cinematography to communicate that Burke is the real deal and someone to worry over.

Burke’s plan is so needlessly more morbid than it needs to be, but this also speaks to its dark brilliance. His target is only Sally, but he proceeds to kill many women who look like her so that her eventual death is misconstrued as the work of a serial killer’s motive instead of a targeted attack. It’s chilling, but also speaks to how complex conspiracies and actions from political terrorists only highlight how little the public really knows. This kind of stuff can happen underneath everyone’s noses with nobody having any idea because of its stealth and invasive nature.

So many De Palma movies about men trying to unsuccessfully save women–perhaps harkening back to De Palma’s own childhood and his sleuthing efforts to videotape his father’s affairs to protect his mother in the process–but Blow Out presents one of the starkest and nihilistic versions of this idea wherein Jack doesn’t only fail to save Sally, but her death and his defeat are forever immortalized on celluloid to entertain millions of audience members. No one can rewind the footage to change Sally’s fate like in “Co-Ed Frenzy.” It’s the grim irony of this theme that recurs throughout De Palma’s works, especially for a filmmaker who so often uses cinema as the ultimate expression of the soul.

This tragic ending comes as such a blow and feels very much representative of the decisions that happen in movies forty years ago versus today. Emotionally, Jack’s final embrace with Sally is a lot to take in, but De Palma also guarantees that it’s just as visually expressive. What follows is one of the most cinematic moments that’s ever been committed to film. The sheer extravagance of the exploding fireworks as Pino Donaggio’s score swells and Travolta loses himself in Jack’s sadness is just a masterpiece. Whether it’s intentional or not, the galaxy of light that’s cast over the dorm room from an illuminated disco ball during Blow Out’s opening scene also works as a visual counterpoint to these fireworks that works as another element that bookends the movie, both through reality and the illusion of cinema.

Let’s talk about De Palma, who thinks in the cinematic language. Think of that rotating shot, the camera looping around as Jack runs around checking his tapes, which have been erased, sounds of film flapping and Jack doing laps like Sisyphus. Think of the split-diopter of Lithgow’s lunatic holding a photograph up as he descends the escalator, of the fish head and the ice pick, the frog and the owl, and the lovers at the bridge. Think of Jack, under the flaming sky of July Fourth fireworks, a patriotic patchwork of red, white, and blue, holding her lifeless body in his arms as the country celebrates its spectacular anniversary.Despite the obviousness of De Palma’s formal skill, Blow Out was initially greeted with indifference, and didn’t get a boost in credibility until Tarantino praised it (it is now rightfully revered, of course). Notably, it stands out in two ways from his other thrillers. He famously has made small movies for himself and big movies for paychecks; this is a small movie made big by a generous budget (by De Palma’s standards, at least). The extra money meant better sets, car chases through parades, many retakes and reshoots, De Palma taking a month off of shooting to think about the script more. And it’s a tragic film, and the tragedy here comes not from pure spectacle, (though there is that, too) but the fact that we care so much about these characters, these performers; we care about Travolta’s doomed-to-fail sound man and Nancy Allan’s doomed-to-die sylph, and when they hurt, we hurt.

This is a film that begins with a murder and a scream, piteous and irritating, and ends with a murder and a scream, pained, one that reverberates deep in the corridors of the heart. De Palma’s deft manipulations of images and sounds are redoubtable, but much of the film’s pure emotional power comes from Travolta’s performance, the sincerity he brings to this tragic would-be hero who, in solving the mystery, in getting the answers he seeks, ends up in his own personal hell, his greatest failure turned into a throwaway shriek coming from another woman’s mouth.

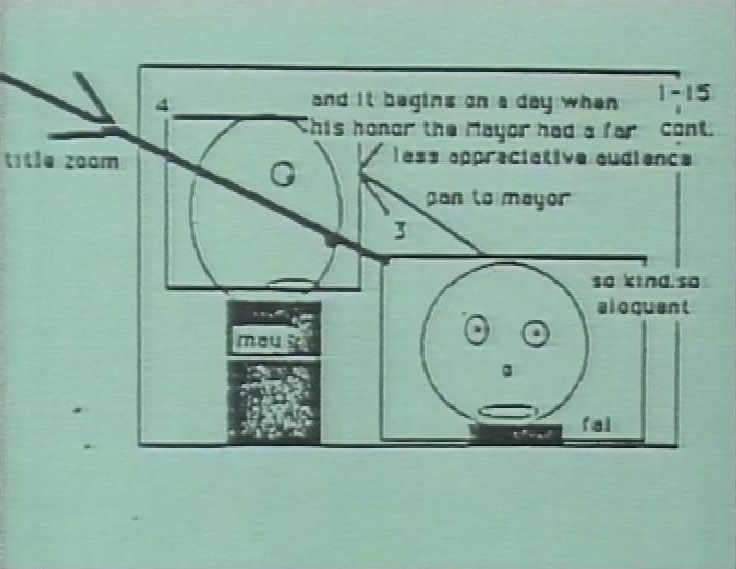

The sound recording sequence is a joy – here we just luxuriate in the art of movie-making. Jack is out by the river, underneath a bridge, recording the natural sounds that he will end up using in the movie – first we hear the sound, then we follow Jack’s mic as it picks up on it, and then we see the source – a frog, a couple having a quiet talk (unlike the chat between the couple in The Conversation, this one’s absolutely harmless), an owl….and something we don’t see the source of – a strange buzzing, winding sound. What the hell is that? We soon find out that it’s Burke pulling and releasing the garrote on his wristband. One of Blow Out‘s main pleasures is giving us little clues and hints that only become truly apparent on a second viewing. It’s not the sort of thing that makes a first watch baffling, just the odd lovely touch that makes further viewings even more satisfying.This key sequence will be revisited many times throughout the movie – Jack will pore over his recording to try and work out what happened, and we the viewer are granted visual reminders of the action. This is taken a step further when Jack acquires a series of still images of the event, taken by Sally’s opportunist sidekick Manny (a scuzzy Dennis Franz). Jack cuts out the images, photographs them and creates a mini-movie to accompany the sound, and it’s essentially like watching a movie being made before our very eyes. De Palma is a classic visual storyteller, and these sequences showcase that love of craft and creation beautifully.

Throughout Blow Out, De Palma deploys his box of tricks superbly to the plot – in addition to split-screen we have his much-loved use of deep focus, as well as long-takes, 360 degree spin-arounds and back-projection. Like with Dressed to Kill, De Palma’s execution of cinematic technique is so kaleidoscopic it makes most other directors works feel awfully monochrome. The substance and the style of his films complement each other to such flawless degrees that his methods are precisely what makes the drama so dramatic. This isn’t just fancy dressing. This is cinematic style at its absolute peak. There’s also another wonderful score by Pino Donaggio. Okay, so his occasional lapses into what I can only describe as the imagined lost incidental music for some cancelled detective show may sound a little dated now, but the main orchestral and piano themes, especially the ones centred around Sally, are absolutely heartbreaking and truly beautiful.

Adam Nayman on Neo-Noir, Criterion Current

Where film noir gained potency from its distorted yet crystalline reflections of a starkly stratified, economically depressed society—a world of detours down nightmare alleys at nightfall—neonoir applied a carefully filigreed lens of nostalgia, aligning it with the returns to western and gangster-movie forms that served as the foundations of the New Hollywood. The eagerness with which writers seized upon and venerated movies like Robert Altman’s The Long Goodbye (1973) and Roman Polanski’s Chinatown (1974)—one a melancholically modernized Raymond Chandler adaptation, the other a sadistic riff on the author’s knight-errant narratives in which the windmills prove un-tiltable—had as much to do with retrospectively elevating their directors’ underlying inspirations as acknowledging their state-of-the-art craft and state-of-the-union cynicism.While the Coens probably prefer The Long Goodbye—they quoted it affectionately in both the Chandler-happy The Big Lebowski (1998) and the non-noirish Inside Llewyn Davis (2013)—it’s Chinatown that feels like neonoir’s early-seventies epicenter, an elegant, scarifying return to the primal scene of Los Angeles in the 1930s. The film’s throwback setting and aesthetics barely belied screenwriter Robert Towne’s post-Watergate cautionary fable about the intersection of establishment political power and patriarchal perversion, both monstrously conjoined in John Huston’s businessman Noah Cross and perceived—perceptively but futilely—by Jack Nicholson’s nosy investigator Jake Gittes, who recognizes the older man’s crimes against city and family alike and can do nothing to stop them. As novelist and screenwriter R. D. Heath writes, “instead of vice being the property of outsiders, drifters, slum-dwellers or dead-eyed suburban losers and predators, [in Chinatown] it flows directly from the most respectable man in town, who aims to be even more respectable . . . the future shall venerate Noah Cross’ name and regard him as a founding father.” When Faye Dunaway’s doomed and diminished Evelyn Mulwray—fated to be both Cassandra and Elektra in the movie’s neo-Grecian schema—cries out of her demonic pater “he owns the police,” the actress’s emphasis on the second word is chilling. It evokes how both individuals and institutions can be held as property, and the image of Huston enfolding his wide-eyed, open-mouthed daughter-slash-granddaughter (Belinda Palmer) is as predatory and unsettling as anything in American cinema. It lays bare a hopelessness that doesn’t feel safely contained by the parameters of the story or the screen, as ancient as the forces coursing through a horror movie like William Friedkin’s The Exorcist (1973), an enduring evil loosed once more upon a fallen world.

Arthur Penn’s Night Moves (1975) revolves around a smuggled sculpture that exists on a continuum somewhere between The Exorcist’s excavated Assyrian totem and the Maltese Falcon: a valuable, cursed antique that turns out to be the stuff that nightmares are made of. Like Chinatown, Penn’s film is a neonoir scribbled in indelible ink, with a cloud of encroaching blackness gradually blotting out the sky on both coasts. There’s a determinedly panoramic sprawl to Alan Sharp’s screenplay, which keeps shifting the action back and forth from gleaming, sun-blind Los Angeles—the prowling grounds for Gene Hackman’s hamstrung football-star turned PI Harry Moseby, a laconic brother shamus to Jake Gittes and Philip Marlowe—to a swampy outcropping of the Florida Keys, where a jailbait heiress has absconded to either visit her stepfather or seduce her mothers’ other lovers . . . or both. Incest remains at the level of subtext (“the world is getting smaller, the kids are getting younger, and I’m getting drunk”), but corruption, coercion, and subterfuge ooze from the story’s every pore.

Penn’s chosen style is much slower and more deliberate than Howard Hawks’s serene velocity in The Big Sleep (1946)—and some shots hold long enough to “watch paint dry,” as per Harry’s priceless, tossed-off critique of/stealth encomium to Eric Rohmer—but it cultivates a similar sense of perpetual, in media res confusion, of endlessly unfolding exposition that explains everything except what’s actually going on. A half-decade before Blow Out (1981), Penn wrings a sinister variation on the Zapruder film via footage of a movie-set car crash that suggests not only an act of behind-the-scenes sabotage claiming the life of a supporting character, but, more widely, a booby-trapped reality. The bloody coup de grâce, meanwhile, is delivered by another, larger vehicle, a horrific act of death from above as the MacGuffin disappears beneath the waves, as lost to the ages as the treasure of the Sierra Madre or all those crisp bills scattered to the wind at the end of The Killing (1956).

Both Chinatown and Night Moves make a determined show of trailing off, of punctuating tragic revelations with slippery ellipses, the former through a wobbly tracking shot that loses sight of its subject, the latter in a long view of a damaged boat tracing figure eights along the ocean’s surface into infinity. Without closure, there can be no catharsis, but some of the strongest neonoirs of the early eighties take a less open-ended approach; they lock into place like iron maidens around their hapless protagonists, fine-tuned mechanisms in an era of high-concept studio engineering. It’s telling that Steven Spielberg and George Lucas’s right-hand man Lawrence Kasdan, the cowriter of The Empire Strikes Back (1980) and Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), was keen to try his hand at another old-school homage, and also that he tried to reinject some of the sexiness that had become neutered in the surrounding blockbuster deluge. In Body Heat (1981)—set, like Night Moves, in Florida mid-heat-wave—William Hurt’s inept lawyer gets warned about “following his dick into a very big hassle.” He ends up in jail for a murder he didn’t commit in lieu of the one he did (a comeuppance copped by the Coens for The Man Who Wasn’t There); meanwhile, confidence woman Kathleen Turner fulfills her high-school-yearbook ambition to “be rich and live in an exotic land.”

Kasdan’s satisfying, putatively progressive girl-on-top scenario deviated significantly from the seventies sacrificial-femme template (and generated reams of academic discourse as a result), while De Palma’s Blow Out ends, much like Chinatown, with the scream of an innocent woman slain on the altar of an upwardly mobile (and spiderily all-encompassing) conspiracy. There will be no forgetting for John Travolta’s soundman, however: his mythic punishment will be to hear her scream over and over, wrecking his own soul on the rocks of the siren’s call; it’s as if De Palma were trying to show Polanski what downbeat really looks like. The one rousing semi-exception to 1981’s roundelay of unhappy endings—a movie with catharsis to burn—is Ivan Passer’s Santa-Barbara-set Cutter’s Way, about a paranoid, disabled Vietnam vet played by John Heard who takes arms against a sea of troubles—and aim at a monstrous, all-consuming local tycoon—by briefly adopting the iconography of the old West. Cutter doesn’t survive his brief, glorious bout of John Wayne cosplay, but his best pal, Bone (Jeff Bridges), shows true grit by pulling the trigger in his stead—a replay of the ending of The Long Goodbye torqued more toward cosmic justice than individual retribution.

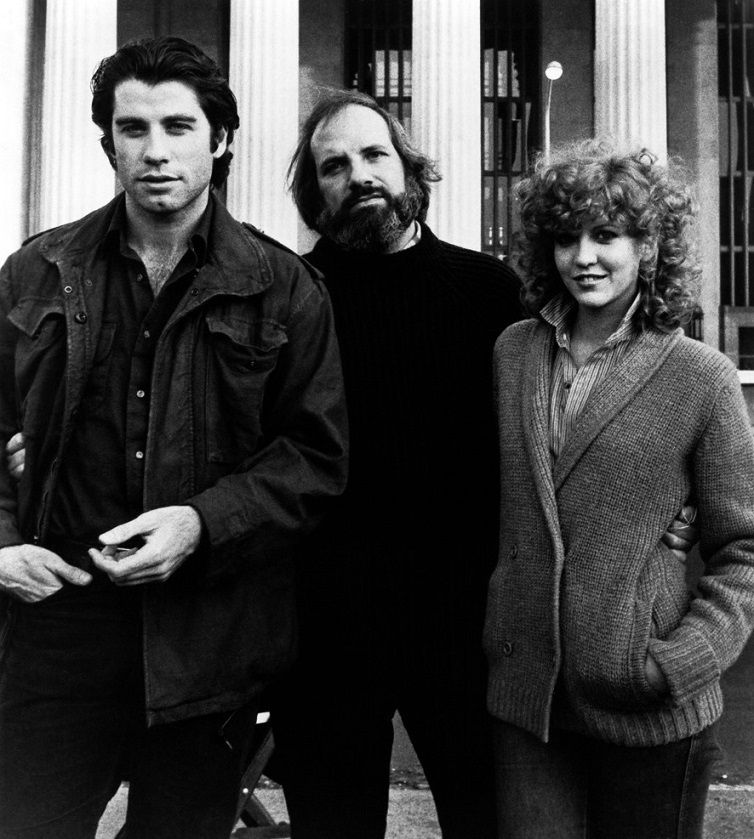

Many years ago, I somehow came into possession of a thick stack of stills and transparencies from Brian De Palma’s BLOW OUT, which marks its 40th anniversary today. Here are a few I just dug up. This superb thriller remains my favorite De Palma. Brilliant filmmaking.

Brian De Palma’s best movie, Blow Out, opens with scene from a movie-within-a-movie, a Z-grade slasher rip-off called Co-ed Frenzy, from the director of such esteemed films as Blood Bath and Blood Bath 2, Bad Day at Blood Beach and Bordello of Blood. The camerawork mimics the killer POV shots of Black Christmas and Halloween, peeping through the windows of a sex-crazed sorority house before ducking inside, where the action alternates between T&A and stabbings. It finally ends with the umpteenth crude variation on the shower scene in Psycho, and the punchline that takes us out of the movie: the actor has a terrible scream.Blow Out is about the sound man, Jack Terry (John Travolta), finding a better scream. It’s also about the movies, and about how easily the truth can be manipulated or obscured. Beyond that, it’s about what America had become after a decade where trust in the government was lost to Vietnam and Watergate, and how conspiracies of the powerful could crush ordinary citizens who happened to get in the way. Here was De Palma at the peak of his talent, making a film that’s politically loaded and emotionally operatic, with great technique, visual wit and an arsenal of sly references to other films and historical events. It’s so multi-layered, yet De Palma can make it feel like a magician’s sleight-of-hand.

Look again at that opening sequence. By that point in his career, De Palma could have people convinced that it wasn’t a movie-within-a-movie at all, but another lurid sequence from a director whose Hitchcockian thrillers were full of voyeurism and high-toned exploitation. After all, De Palma had already opened a film with a tracking shot through a girls locker room in Carrie and he had already done a softcore homage to Psycho in Dressed to Kill, which had Angie Dickinson lathering up while we anticipate her early exit. De Palma pulling out of the fake movie with that awful scream is not only a terrific joke, but a primer for the deconstructive trickery of the rest of the film. We’ll need to question everything we see and hear.

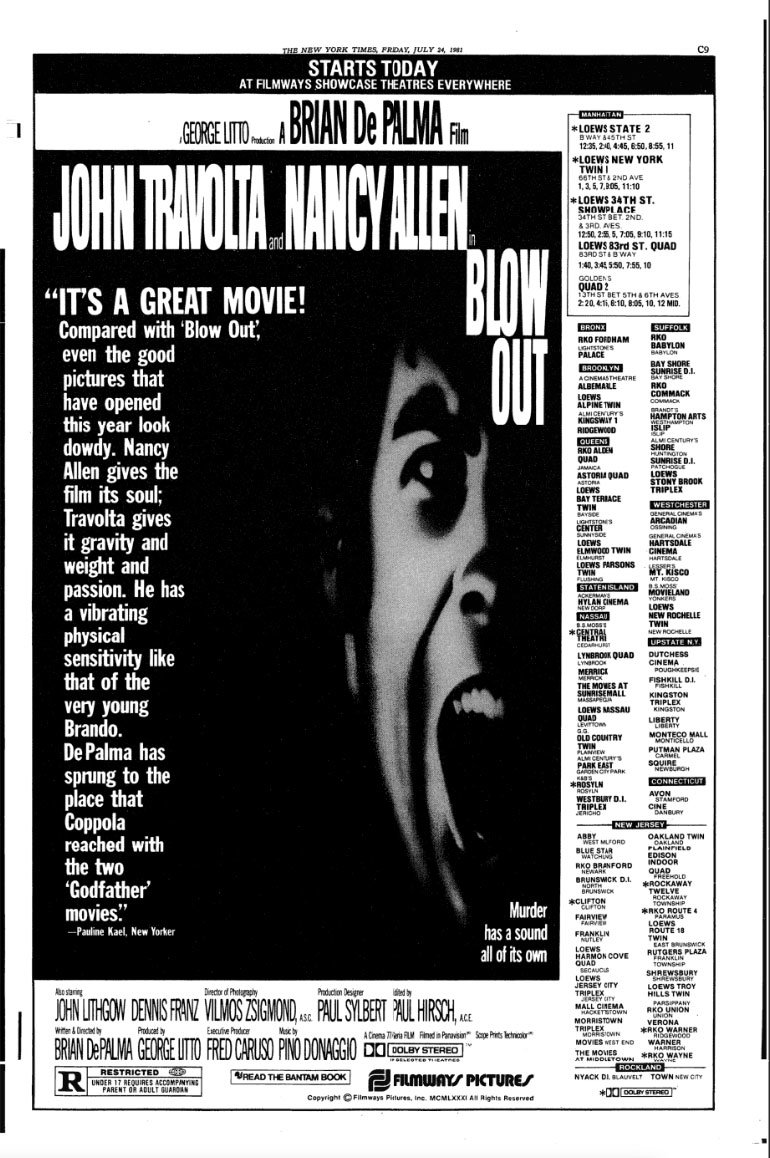

Despite garnering some of the best reviews of De Palma’s career, Blow Out tanked when it came out 40 years ago, most likely because audiences found the ending too despairing. Who could guess that juxtaposing the bicentennial celebration with a murder and a cover-up wouldn’t be commercially sound? But the film has lost none of its power over the years, as we’ve sunk deeper and deeper into media manipulation, conspiratorial thinking and a greater opacity among the governing elite and their ultra-wealthy patrons. What is, say, Jeffrey Epstein’s prison suicide but a Brian De Palma film waiting to happen?

True to form, De Palma used the films of the past as the building blocks to construct Blow Out, most directly Blow-Up, the 1966 Michelangelo Antonioni thriller about a fashion photographer who believes he’s captured a murder on a shoot, and Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation, itself a play on Blow-Up, only about a surveillance expert who believes he’s captured a murderous political conspiracy on tape. What De Palma did in conceiving his film was simple math: Blow-Up + The Conversation = Blow Out. Or, put another way, Image + Sound = Film.

The sound part comes first. The director of Co-ed Frenzy sends Jack out to get fresh sound effects, so he heads to a Philadelphia park at night with his microphone wand to get some authentic wind noises and the like. He happens to have the recorder on when a Chappaquiddick-like incident happens off in the distance, with a car careening off a bridge and into the creek water below. Jack rescues the young woman inside, Sally (Nancy Allen), and accompanies her to the hospital, where he learns that the driver of the car is a popular governor who could be the next president. One of the governor’s handlers takes him aside: would he mind, for the sake of the deceased’s wife and family, keeping his mouth shut about Sally being in the car?

The image part comes next. By a crazy coincidence, a sleazy photographer (Dennis Frantz) was also in the park and caught the incident on film, which he then sold to a tabloid, which prints the footage frame by frame. Only it’s not a coincidence: the photographer and Sally have been shaking down wealthy two-timers by putting them in a compromising position and asking for cash in exchange for the shots. Meanwhile, Jack makes something like a full-sound Zapruder film by syncing his recording with the printed frames, confirming his suspicion that the car’s tire was shot out before it veered off the bridge. He and Sally now possess knowledge too dangerous for them to have.

From there, Blow Out takes the basic form of the classic 70s political thriller, like The Parallax View or Three Days of the Condor, but De Palma gives the film a florid grandeur that’s far removed from the chilly paranoia of those earlier films. Travolta and Allen are fully invested in characters who develop a romantic bond under duress, and so when the stakes get high and the danger mounts, De Palma’s signature set pieces have a genuine emotional flavor on top of the amplified suspense. The ending seems particularly harsh because we’re so invested in Jack and Sally’s survival, along with the faint hope that justice against the powerful is possible to achieve in America.

Jack gets his scream in the end, but it’s a final, bitter irony that only he knows its source. The sound and images that Jack had once put together to reveal the shocking truth about a supposed accident are now gone, and the most horrific moment of his life is now ADR for a fictional piece of garbage. As a movie about making movies, Blow Out not only pulls the curtain back on how film-making works, but challenges the audience to question the reality of a medium that’s based around an optical illusion. Believe it or not, there are image-makers out there more sinister than Brian De Palma.

Andy Crump, Paste

Blow Out Remains Brian De Palma's Politically Cynical Masterpiece

Brian De Palma’s Blow Out turns 40 years young eight months after the Democrats’ clear-cut victory in the 2020 general election, and throughout that interminable stretch of time, a disinformation campaign about the election’s results that’s best represented by the Jeremy Bearimy timeline has been pushed by too many members of the GOP for comfort. People don’t assassinate American presidents in the 2020s. Instead, they spew whatever easily disproved batshit nonsense they can conjure on social media, where the lies metastasize into truth for the same crowds of gullible chumps Barnum rightly called “suckers.” It’s enough to make you miss seedy, clandestine murder conspiracies.Scurrilous balderdash is the bread and butter that’s fed the American right wing since the days of Richard Nixon, William F. Buckley and Roy Cohn, and even before then. Part and parcel of the liars’ strategy is the cover-up—a concerted, smug attempt at obfuscating facts and covering the keister of everyone involved in the lie. Andrew Clyde characterized the January assault on the U.S. Capitol as a “normal tourist visit.” Kevin McCarthy, formerly opposed to a January 6th investigative commission, has handpicked a pack of lying slack-jawed yokels, including Jim Jordan, for his own commission.

Will these scumbag elected officials get away with muddling the roots of political violence? Maybe. Blow Out doesn’t really care, not in any overt way. The film doesn’t wear politics on its sleeve, though it is undeniably a political work of grimy art. It does, however, tell De Palma’s narrative through a politically aware lens, even if the argument he ultimately makes about politics and politicians is that they’re infinitely scuzzier than the boobs ‘n’ blood exploitation movie-within-a-movie Blow Out opens on. (For that matter they’re scuzzier than most of De Palma’s pictures, too.)

George McRyan, the Pennsylvania governor and presidential hopeful the audience learns about on a TV news broadcast, isn’t identified explicitly as either Democratic or Republican. Liberal viewers may interpret McRyan who, based on polling appears poised to win the general election in a landslide, as liberal due not only to his broad popularity compared to the movie’s sitting president, but where his popularity gets him: Lifeless on a hospital gurney. Republican viewers might assume the opposite.

Standing between them and on the opposite side of Blow Out’s lens, De Palma doesn’t give one solid damn. He’s not interested in his conspiracy thriller’s politics, not directly anyway. He’s interested in making Blow Out’s life into an imitation of art, and telling a story about the vast individual components of filmmaking that, when brought together, find the film’s sum. Movies are made of more than scripts and actors and fancy camera angles. They’re made of noise, too.

Jack Terry (John Travolta), De Palma’s laid back sound tech protagonist, engages noise in his work and in the world surrounding him. It’s a passion. He stands at tranquil ease on the Wissahickon Bridge, scanning the area for new aural wonders to capture with his Nagra recorder, waving his mic around like a magic wand as if he’s a wizard and his gadget is the source of his arcane power. A contingent of cinephiles today think of De Palma only as a smut purveyor, and while they’re not wrong, exactly, that read is narrow verging on oversimplified. De Palma likes his sleaze. He also likes cinema as art. He’s in many ways the ultimate cinephile, someone born to make movies and who understands how movies speak to an audience. In Blow Out, he demonstrates that understanding within and without the frame: Calling this his best film is an easy layup, but it’s quite possibly true, and if not then it’s certainly his best display of bravura.

Do you like split diopters? Do you enjoy seeing an entire image in deep focus, such that the foreground and background become a single balanced entity? If that’s your thing, you’ll lose your mind when Jack records an owl’s hoot and De Palma fills half the frame with Travolta and the Nagra, and the other with the noble nocturnal bird of prey staring down the viewer up close, contempt blazing in its eyes. When Burke (John Lithgow), the remorseless iceman responsible for McRyan’s demise—another candidate hires him to catch McRyan in a compromising position with Sally (Nancy Allen), an escort, but Burke zigs instead of zagging and chooses to kill McRyan instead—stalks a woman he confuses with Sally through a market at night, the camera lands on the dead, lolling stare of a fish on ice. Burke’s hand reaches into the display to seize an ice pick as “Sally” walks through the back door, illuminated in red light.

The pleasure in Blow Out is the naughty thrill De Palma whips up in an artful, skillfully composed shot executed with advanced filmmaking techniques. This is a really dry way of saying that his work looks great, so great in fact that his craftsmanship belies the material’s indecency. These contradictions coexist harmoniously in the same space. It’s a matter of tone. Sleaze can be exquisite. In fact, the higher De Palma aims, the more we appreciate the sleaze as an element with purpose, because the grandeur of Blow Out’s filmmaking imparts on the plot a sense of scale: De Palma swings big, and by swinging big he emphasizes just how small Jack is in the scheme of things. He’s naïve at best, doomed at worst, and at all times a cog in a society run by powerful, unscrupulous men. There’s nothing he can do to stop the machine’s gears from turning, doggedly as he tries.

Deep focus and basic split screens, another of De Palma’s favorite flourishes, function as other ways of seeing in Blow Out. The film shows us Jack’s efforts to save the day and stacks them against the inevitability of his failure. A surface take on De Palma’s aesthetic is that it looks cool, a detail De Palma prizes as highly as sleaze. But the “cool” is an admission of his pessimism. The act of “seeing” he performs throughout Blow Out is the bluntest tool in his belt, intended to hammer home that McRyan’s death is set in motion by the unstoppable wheels of American political intrigue.

In the end, Burke dies. It’s a small victory. Sally dies, too, and that traditional American celebratory lubricant, the fireworks display, bursts overhead as Jack cradles her body in his arms; the explosive exuberance mocks his grief, rubs in his defeat and reminds us in the audience that the deaths of people like Sally—small people, the socially undesirable types on America’s fringes—are inconsequential to the United States’ political designs. George McRyan is dead. A salvo of brocades, mines, Roman candles and tourbillons for George McRyan. Sally Bedina is dead. Who the hell cares? The fireworks tell the myth of how Americans see themselves and how they see their country. Sally’s limp form and Jack’s defeated gaze tell the sordid truth.

It’s a truth only De Palma and the audience recognize. When Blow Out ends, the lie holds. The cover-up stands. Justice is left undone. The only truth left is Sally’s scream, a nerve-shredding wail immortalized by Jack’s recorder. What will immortalize the dead bodies in the aftermath of January 6th, and bodies yet to come, as Democrats struggle in vain to stem Jordan, McCarthy and Clyde’s corrosive falsehoods flooding the account of what really happened at the Capitol that day? Again, Blow Out answers with truth: Nothing that will mean a damn or make a difference to America’s trigger-happy jingoistic spirit. If De Palma’s a cynic, then he’s a cynic behind a masterpiece we can all still relate to.

In many respects, “Blow Out” is a recapitulation of the various obsessions that had been driving De Palma throughout his entire career. The murder of the governor is obviously meant to evoke memories of the JFK assassination (with a hint of Chappaquiddick thrown into the mix) and Jack’s dogged attempts to expose the vast conspiracy surrounding it to a public that may not ultimately care is reminiscent of Gerrit Graham’s attempts to crack the Kennedy conspiracy in De Palma’s audacious social satire “Greetings” (1968). Beyond that specific plot concept, the film touches on such elements as voyeurism; a cynical take towards contemporary entertainment; modern technology and the dangers that can come from putting one’s faith entirely behind it; and deeply flawed heroes who are struggling to find some kind of redemption and either fail at it or succeed, only to discover that the price to achieve it may ultimately not be worth it.Part of De Palma's genius comes from presenting his narratives in such stylish and striking visual terms that it isn’t until later on that you realize not everything adds up. While the aforementioned “Blow-Up” and “The Conversation” are undeniable inspirations for the film—all three involve emotionally isolated men with a particular skill set that they attempt to utilize when they stumble upon murder plots—De Palma uses such a conceit in "Blow Out" only as a mere leaping-off point for his own unique take on the premise. The resulting screenplay is a bit of a miracle, as it offers a narrative as dense and complex as any that he had done up to that point (or since then), but in a surprisingly graceful and straightforward manner. With "Blow Out," De Palma allows viewers to grasp what's going on without letting them get lost in the labyrinth (except when that's the point, of course) and without any extraneous bits of business. Even the stuff that appears to be extraneous, such as the “Coed Frenzy” opening or a spree of murders of prostitutes, all ends up fitting together in the big picture that De Palma presents with jigsaw precision.

Like practically all of De Palma’s key films, there are a number of elaborately constructed set pieces in "Blow Out" that bring his considerable skills as a visual stylist to the forefront. But unlike some of his other films, such sequences are so perfectly integrated into the storyline they never feel like he's showing off. Obviously, the "Coed Frenzy" opening is a standout that illustrates that while he's perfectly capable of cranking out mindless exercise in violent style—the kind that he has often been accused of making throughout his career—he's no longer interested in such a lack of artistic challenge. There's also the haunting flashback sequence in which Jack recounts his days with the police and the case where everything went wrong, which serves both as a compelling way to fill in his backstory and explain his cold, cynical attitude towards everything, and to allow De Palma to show what he might have made of “Prince of the City,” a project he was scheduled to do even before “Dressed to Kill” but which he lost out on when the producers elected not to wait a year for Robert De Niro’s schedule to clear up and instead gave it to Sidney Lumet. (This sequence, originally devised for De Palma's version, will make you look at De Palma's "Prince of the City" as one of the great unmade movies.)

The climactic chase, in which Jack speeds through the crowded streets of Philadelphia (at one point barreling through the middle of a parade) to rescue Sally fro mthe deadly trap that he has inadvertently placed her in, is such a miracle of filmmaking—both in terms of sheer technique and the emotions that it engenders—that Hitchcock himself would have doubtlessly bowed to it out of sheer admiration. (The scene is especially impressive when you realize that De Palma was forced to reshoot it at the last second, after all the footage he shot vanished when the truck carrying it was stolen.) However, the most spellbinding sequence in the film—possibly of De Palma’s entire oeuvre—comes when Jack, using his audio recording and a collection of photographs of the accident published in a magazine a la the Zapruder film, creates a mini-movie that proves once and for all that it was anything but an accident. A scene like this in a contemporary film would be all but unimaginable, and not just because of the massive changes in technology—it has to go on for a while or else it simply doesn’t work. As shown here, it's not only a completely spellbinding exercise in pure cinema but it also serves as beautiful and potent a display of the seductive allure of the filmmaking process as has ever been put up on the screen.

With the major exception of Sissy Spacek's character in “Carrie,” De Palma's characters were oftentimes essentially pawns that he moved around like chess pieces and whom it was sometimes difficult to relate to on an emotional level. Here, the central characters of Jack and Sally are both fleshed out and ultimately engaging despite their flaws, which not only allows viewers to develop an actual rooting interest in them but also gives the finale the overwhelmingly powerful punch that it might not have otherwise produced. Of course, the ability to care about these characters comes in no small part from the truly inspired performances behind them. For example, I don’t think that I am going too far out of line when I suggest that Travolta (who first worked with De Palma and Allen on “Carrie”) has made a number of films that are of a somewhat dubious nature—so many that while the aforementioned “Moment by Moment” was once regarded as a potential career-killer, it probably would not even rank among his ten worst films. However, one thing that you can say about him is that even in the worst and most ill-advised of his projects, you rarely see him simply coasting through a part—even in something like “Battlefield Earth” or “Gotti,” he is always putting in 100% effort. When he puts that approach in the service of a worthy screenplay and role, as is the case here, the results can be extraordinary. Beautifully suppressing the natural charm that helped make him a star but which would have been all wrong here, he plays Jack as a cold fish who has willingly removed himself from the world in order to avoid getting hurt and as he struggles tome the choice to care and reengage once again, he manages to engage viewers without breaking his character. Even though he is a mess, we still root for him and when it all goes wrong, we are just as shattered as he his in the film’s unforgettable final shot. This is by far the finest performance of Travolta’s career—even his turns in “Saturday Night Fever” (1977) and “Pulp Fiction” pale in comparison to it—and one of the biggest tragedies of the eventual failure of the film is that few people saw it at the time are realized what he was capable of doing.

The other key performances in the film are nothing to sneeze at either. When the film came out, there was much criticism that Allen (in what would be the last of the four films she did with De Palma, whom she was married to at the time) was merely playing a downscale version of the high-class sex worker she portrayed so memorably in “Dressed to Kill.” Like so much of the criticism of the film at the time, this observation was not entirely accurate and fails to take into account just how engaging and likable she is in the role—Sally may be a bit naive in certain regards but she is far from being just a mindless bimbo and, as is the case with Jack, we genuinely care about what happens to her during the breathless finale. More importantly, although the film smartly avoids any hint of a conventional romance between Jack and Sally, the onscreen chemistry between the two is off the charts, so much so that one can almost picture them taking those exact same characters and spinning them off into a potentially fascinating romantic comedy.

And since a film of the sort has a tendency to live or die on the strength of their villains, “Blow Out” is blessed with two equally strong performances in the bad guy roles. As the sleazy photographer, Dennis Franz (who had small roles in “The Fury” and “Dressed to Kill”) is an absolute hoot as a guy who suggests what might result if a stained T-shirt suddenly became a sentient life form. John Lithgow, who worked with De Palma on “Obsession” (1976) and would later reunite with him on “Raising Cain” (1992), is a scream of an entirely different and more chilling manner, as someone who suggests a cross between G.Gordon Liddy and the serial killer character that Lithgow would later play so memorably on “Dexter.”

In the wake of the failure of “Blow Out,” De Palma quickly signed on to do the splashy, big-budget remake of “Scarface” (1983). He continued with a career that would continue to raise the hackles of critics and audiences alike while hitting upon the occasional success with films like “The Untouchables” (1987) and “Mission: Impossible” (1996) that allowed him to channel his undiminished filmmaking skills into a more commercially viable framework. The one downside is that, with the exceptions of the war dramas “Casualties of War” (1989) and “Redacted” (2007), De Palma never really tackled material as serious-minded again, even though he proved himself more than capable of with it.

And yet, the reputation of "Blow Out" has continued to grow in the 40 years since it first came out. While the technological aspects have certainly changed, the story has not aged at all—in an era in which people are more willing than ever to find conspiracy in everything, it now feels more in sync with the times than ever before and even the infamous finale feels like less of a shock. It remains a work of stunning cinematic craft from one of our greatest, if too often undervalued, filmmakers and while he has made any number of other great movies over the years, this is the one he deserves to be remembered for above all.

Here’s how we define the De Palma Gaze: a macho, threatening perspective that audiences and academics can’t decide if they like or not. Some even call him a “talented recycler who riffed on the movies of great auteurs.” I unfortunately absolutely dig him. Each time I watch, I get to psychoanalyze this troubled man’s unfiltered patriarchal mind that’s as primal as a cromageden man. His force-fed binary world of heroes and villains kill, snoop, and ogle womens’ bodies. His work is easy to understand and unapologetically male – and I love it. Am I just curious about how men think? I have no idea, but I am highly entertained regardless. I know he’s problematic, but I can’t help it.BLOW OUT is a lot less bloody and a lot more cerebral than De Palma’s other flicks. It’s a conspiracy-driven thriller set in a complicated world of fixers, violence, and good samaritans forced to rise to the occasion. While it may not host an uplifting finale, it’s an ending flush with morality and satisfaction that lingers in ambiguity. BLOW OUT delivers intrigue while maintaining a concise, relatable story. Going up against the big guns of the political establishment might not pan out, but we are compelled to roll up our sleeves and dig because we might find something, anything at all. It’s a tight story with intimate cinematography, and scarily meta sound design all while showcasing a career-best Travolta: this is cited as the main reason why Tarantino cast the declining actor as Vincent Vega in PULP FICTION. His two greatest performances are both thanks to the mind of Brian De Palma.

Each time I rewatch BLOW OUT, I gain a greater thrill in sinking into the blitzed out world of 1981. There’s a new edge or angle to bridge between my personal experience and the film. If there was a systemic issue at my job where I had to find a solution within an insanely bureaucratic process, the political roadblocks and bad actors felt minimal compared to a menacing John Lithgow. While Donald Trump was rarely held accountable for corruption, BLOW OUT was clear in its stance. Consumers getting poisoned by baby food or sunscreen without regulation validated my feelings about how the government views citizens: I could inhabit a world where chipping away with my curiosity and livelihood would reveal the truth. Watching John Travolta pick at the scab of a murder plot is the allegory that salves my anxieties. It’s both a facsimile of our unique political fears and an entertaining escape. There is a resounding, thrilling identification in watching Travolta as Jack Terry piece together his snuff sound recording. Terry’s motive, borne out of obsession, ushers him into a new world. His comically banal gig recording female screams for low-budget horror films becomes secondary to this new purpose for the supposed greater good. It’s bleak, but hilarious that the film culminates with Jack transformed and splicing in the perfect scream to the soundscape of a project; his lover and investigative partner’s recorded death wail, the witness to the political assassination.

De Palma likely gets omitted from the New Hollywood pantheon because the early ‘80s slate of culture gets overshadowed by both dying disco and the policies of Reagan’s second term. The post-70s boom-and-bust mentality rippled throughout the industry and in the lives of average people. Blockbusters with special effects were favored by studio capital, and Oscar-bait period pieces became ubiquitous money-makers. Visions of world peace and environmental justice were fluffy pipedreams leftover from the 70s. If we’re only here on this planet for a short time, we better make it a good one. BLOW OUT is coming-of-age decades later, while also being one of the finest films of the Reagan era. J Hoberman, veteran film critic for The Village Voice, came out with his critical anthology on the period Make My Day: Movie Culture in the Age of Reagan in 2019. In it, he references BLOW OUT, and has spoken to the distrust and the rampant anti-government sentiment radiating on and off the screen at the time of its release. Violent crime (and the conservative fear mongering of said crimes) was peaking in the United States, and stagflation and fraught geopolitics stoked further fears. A failed Carter administration did little for progressive causes, so why bother? BLOW OUT is such a visceral picture even today because it captures the disappointment and anguish. It tells the viewer exactly how the world is while acknowledging that we are not just pawns, but stakeholders. Our society is one we can attempt to fix, but are embattled by a system that is impossible to overthrow.

We’re living through a time of great political and cultural transition; post-Trump, major income inequalities, active climate disasters, post-vaccination resettlements, and a looming threat of inflation. The early ‘80s eerily resonate, and alarmingly so! I’m hoping our bleak news environment, and (hopefully) evolved population can appreciate a film of this nature. Violent fare tinged with a liberal morality is much more popular these days, so perhaps it’s finally BLOW OUT’s time in the sun. There are few happy endings in De Palma’s universe, but they are no less satisfying. Even if it’s impossible to win, we root for those with good intentions. I hate that I’m so fascinated by what these men have to say, but I’m here for it.

This week marks the 40th anniversary of my favorite movie, so of course I'm taking the opportunity to write about its director, Brian De Palma."Blow Out" earned decent reviews when it was released on July 24, 1981, but wasn't a hit, particularly when you consider that leading man John Travolta was just about the biggest movie star on the planet. His "Grease" audience apparently didn't want to see him in an adult drama with a bummer of an ending. Also, the movie's borrowings from "Blow-Up," the Watergate and Chappaquiddick scandals and the Zapruder film didn't sit well with 1981 audiences, who were ready to move on from all that stuff. But De Palma's thriller is now seen as one of the underrated films of the time.

Still, there's the Alfred Hitchcock thing.

Throughout his career, De Palma has been knocked as a Hitchcock imitator and it's true that he echoes Hitch tropes: icy blondes, protagonists wrongly accused of murder, characters who double each other, loners who can't convince anyone they witnessed a crime, Freudian explanations for aberrant behavior (although De Palma usually lampoons those explanations).

That knock has faded. Decades of hip-hop sampling and remixes may have made us more comfortable with the idea that all artists draw on previous artists, even Shakespeare. But what's interesting about De Palma is that, while the plot similarities to Hitchcock are legit, he's a much different filmmaker. Even when he's obsessing over the same themes — as in "Obsession," practically a "Vertigo" remake — De Palma explores them with fresh eyes.

Consider his love of extremely long takes, such as the one that opens "Snake Eyes" or another that encapsulates an entire relationship between strangers in "Dressed to Kill." They owe nothing to Hitchcock, who was more interested in building sequences in the editing room than the camera. Those scenes — there's one in practically every De Palma work — are a key to how he sees movies. De Palma uses long, edit-less sequences to persuade us to follow him on the ride he's planning. "I'm not hiding anything," he seems to be saying. "You can trust me."

We can't, of course — there are always twists — but the idea is that De Palma lets us in on the moviemaking process. That's also true of the movies-within-movies he often includes and of his fondness for splitting the screen in half, to show two scenes at once. Reminding us that we're watching a movie also reminds us that he has us exactly where he wants us; there's extra joy in a De Palma thriller because he reveals his tricks. He has such control of movie mechanics that how he tells a story is as interesting as the story itself.

That can fall flat. No amount of formal brilliance can make a bad script like "Mission to Mars" or "Redacted" good, but he has made a bunch of terrific movies that didn't make my top seven: "Femme Fatale," "Snake Eyes," "Mission: Impossible" and more. When everything comes together for De Palma, it's like a guy who loves the movies more than anything is helping us see why he loves them.

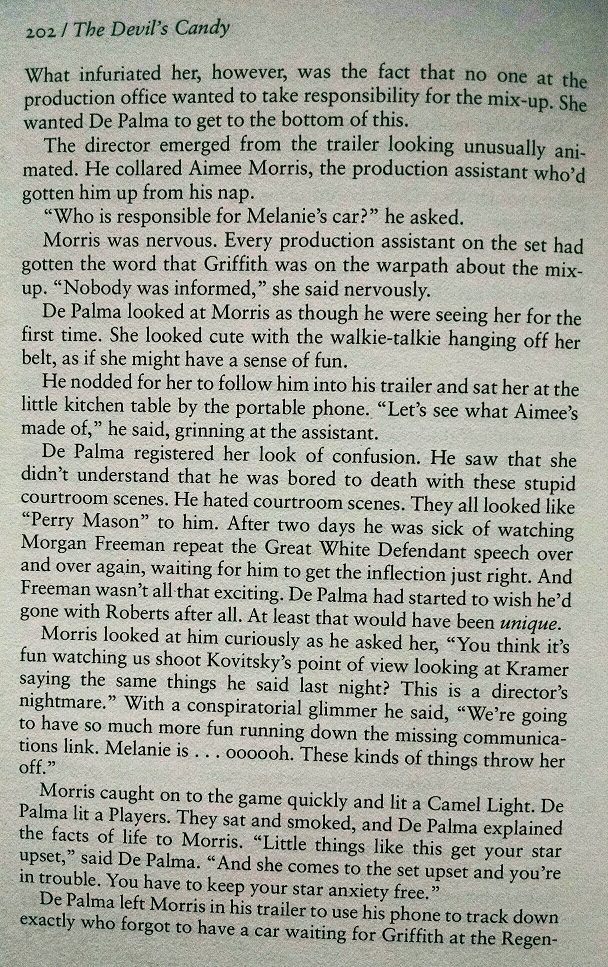

The new episode of TCM's The Plot Thickens: The Devil's Candy delves into that opening steadicam shot of The Bonfire Of The Vanities. The episode is titled "Wire Without a Net," after a chapter in Julie Salamon's book, and features new interviews with Larry McConkey, Aimee Morris (DeBaun), and Chris Soldo, as well as voices from Salamon's original tapes: Melanie Griffith, Morgan Freeman, Bruce Willis, Tom Wolfe.