"BECAUSE IT CAPTURES THE DISAPPOINTMENT AND ANGUISH", WRITES HILARY JANE SMITH

"Brian De Palma’s political thriller, Blow Out, turns forty, and the celebration will likely be patchwork and muted," begins Hilary Jane Smith, in an article at Merry-Go-Round Magazine. "The film is a lonely, forgotten slow burn, one whose quiet success is akin to the slow-but-steady demeanor of Jack Terry (John Travolta) amassing audiotapes." Smith emphasizes that she "apologetically" loves "the work and spirit of Brian De Palma," calling him arrogant, "a man of great ego that tells stories where men are dogs, and beautiful, troubled women are raped, murdered, and bullied by those problematic men… But then saved by other men with 'good intentions.'" A few sentences later, she adds, "I unfortunately absolutely dig him." Here's more:

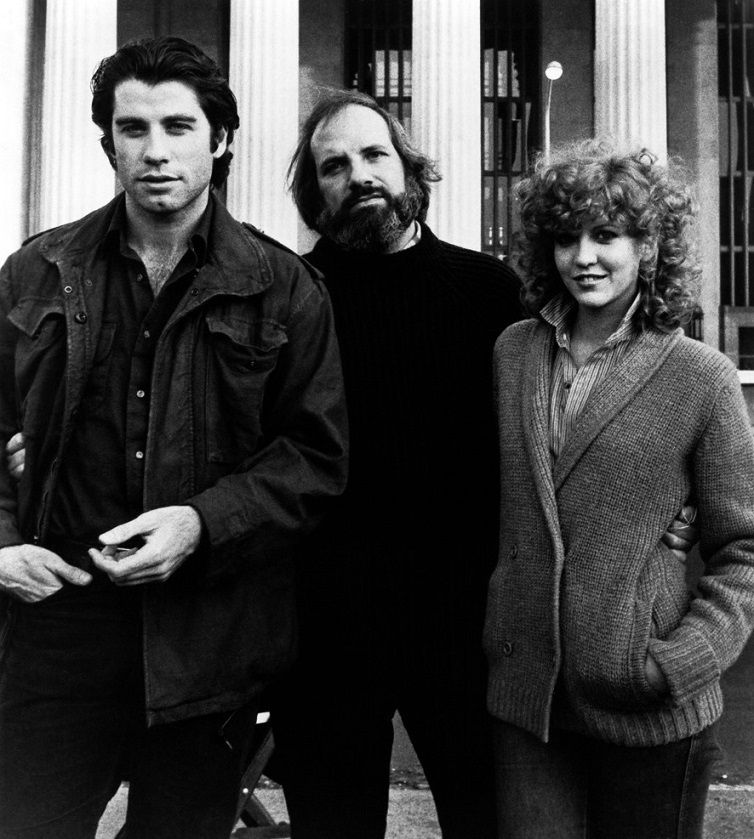

Here’s how we define the De Palma Gaze: a macho, threatening perspective that audiences and academics can’t decide if they like or not. Some even call him a “talented recycler who riffed on the movies of great auteurs.” I unfortunately absolutely dig him. Each time I watch, I get to psychoanalyze this troubled man’s unfiltered patriarchal mind that’s as primal as a cromageden man. His force-fed binary world of heroes and villains kill, snoop, and ogle womens’ bodies. His work is easy to understand and unapologetically male – and I love it. Am I just curious about how men think? I have no idea, but I am highly entertained regardless. I know he’s problematic, but I can’t help it.BLOW OUT is a lot less bloody and a lot more cerebral than De Palma’s other flicks. It’s a conspiracy-driven thriller set in a complicated world of fixers, violence, and good samaritans forced to rise to the occasion. While it may not host an uplifting finale, it’s an ending flush with morality and satisfaction that lingers in ambiguity. BLOW OUT delivers intrigue while maintaining a concise, relatable story. Going up against the big guns of the political establishment might not pan out, but we are compelled to roll up our sleeves and dig because we might find something, anything at all. It’s a tight story with intimate cinematography, and scarily meta sound design all while showcasing a career-best Travolta: this is cited as the main reason why Tarantino cast the declining actor as Vincent Vega in PULP FICTION. His two greatest performances are both thanks to the mind of Brian De Palma.

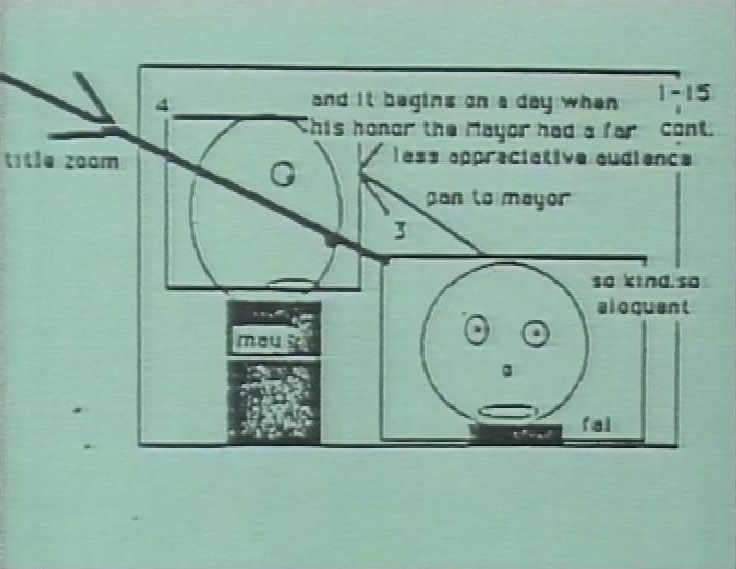

Each time I rewatch BLOW OUT, I gain a greater thrill in sinking into the blitzed out world of 1981. There’s a new edge or angle to bridge between my personal experience and the film. If there was a systemic issue at my job where I had to find a solution within an insanely bureaucratic process, the political roadblocks and bad actors felt minimal compared to a menacing John Lithgow. While Donald Trump was rarely held accountable for corruption, BLOW OUT was clear in its stance. Consumers getting poisoned by baby food or sunscreen without regulation validated my feelings about how the government views citizens: I could inhabit a world where chipping away with my curiosity and livelihood would reveal the truth. Watching John Travolta pick at the scab of a murder plot is the allegory that salves my anxieties. It’s both a facsimile of our unique political fears and an entertaining escape. There is a resounding, thrilling identification in watching Travolta as Jack Terry piece together his snuff sound recording. Terry’s motive, borne out of obsession, ushers him into a new world. His comically banal gig recording female screams for low-budget horror films becomes secondary to this new purpose for the supposed greater good. It’s bleak, but hilarious that the film culminates with Jack transformed and splicing in the perfect scream to the soundscape of a project; his lover and investigative partner’s recorded death wail, the witness to the political assassination.

De Palma likely gets omitted from the New Hollywood pantheon because the early ‘80s slate of culture gets overshadowed by both dying disco and the policies of Reagan’s second term. The post-70s boom-and-bust mentality rippled throughout the industry and in the lives of average people. Blockbusters with special effects were favored by studio capital, and Oscar-bait period pieces became ubiquitous money-makers. Visions of world peace and environmental justice were fluffy pipedreams leftover from the 70s. If we’re only here on this planet for a short time, we better make it a good one. BLOW OUT is coming-of-age decades later, while also being one of the finest films of the Reagan era. J Hoberman, veteran film critic for The Village Voice, came out with his critical anthology on the period Make My Day: Movie Culture in the Age of Reagan in 2019. In it, he references BLOW OUT, and has spoken to the distrust and the rampant anti-government sentiment radiating on and off the screen at the time of its release. Violent crime (and the conservative fear mongering of said crimes) was peaking in the United States, and stagflation and fraught geopolitics stoked further fears. A failed Carter administration did little for progressive causes, so why bother? BLOW OUT is such a visceral picture even today because it captures the disappointment and anguish. It tells the viewer exactly how the world is while acknowledging that we are not just pawns, but stakeholders. Our society is one we can attempt to fix, but are embattled by a system that is impossible to overthrow.

We’re living through a time of great political and cultural transition; post-Trump, major income inequalities, active climate disasters, post-vaccination resettlements, and a looming threat of inflation. The early ‘80s eerily resonate, and alarmingly so! I’m hoping our bleak news environment, and (hopefully) evolved population can appreciate a film of this nature. Violent fare tinged with a liberal morality is much more popular these days, so perhaps it’s finally BLOW OUT’s time in the sun. There are few happy endings in De Palma’s universe, but they are no less satisfying. Even if it’s impossible to win, we root for those with good intentions. I hate that I’m so fascinated by what these men have to say, but I’m here for it.