IN BLOW OUT, 'DE PALMA SWINGS BIG'

"AND BY SWINGING BIG, HE EMPHASIZES JUST HOW SMALL JACK IS IN THE SCHEME OF THINGS"

Two more strong critical appreciations of

Blow Out as the film's 40th anniversary nears, including an excerpt from

Peter Sobczynski. Sobczynski, who considers De Palma to be his favorite filmmaker, regards

Blow Out as De Palma's "greatest cinematic achievement." And, as "a film that I have loved and admired since I first saw it nearly 40 years ago," Sobczynski adds, "I would go so far as to proclaim it both one of the finest American films of its era and one of my all-time favorites to boot." An excerpt from Sobczynski's article is below, but first,

Andy Crump shows how De Palma's political lens from 40 years ago reflects what is happening in the here and now...

Andy Crump, Paste

Blow Out Remains Brian De Palma's Politically Cynical Masterpiece

Brian De Palma’s Blow Out turns 40 years young eight months after the Democrats’ clear-cut victory in the 2020 general election, and throughout that interminable stretch of time, a disinformation campaign about the election’s results that’s best represented by the Jeremy Bearimy timeline has been pushed by too many members of the GOP for comfort. People don’t assassinate American presidents in the 2020s. Instead, they spew whatever easily disproved batshit nonsense they can conjure on social media, where the lies metastasize into truth for the same crowds of gullible chumps Barnum rightly called “suckers.” It’s enough to make you miss seedy, clandestine murder conspiracies. Scurrilous balderdash is the bread and butter that’s fed the American right wing since the days of Richard Nixon, William F. Buckley and Roy Cohn, and even before then. Part and parcel of the liars’ strategy is the cover-up—a concerted, smug attempt at obfuscating facts and covering the keister of everyone involved in the lie. Andrew Clyde characterized the January assault on the U.S. Capitol as a “normal tourist visit.” Kevin McCarthy, formerly opposed to a January 6th investigative commission, has handpicked a pack of lying slack-jawed yokels, including Jim Jordan, for his own commission.

Will these scumbag elected officials get away with muddling the roots of political violence? Maybe. Blow Out doesn’t really care, not in any overt way. The film doesn’t wear politics on its sleeve, though it is undeniably a political work of grimy art. It does, however, tell De Palma’s narrative through a politically aware lens, even if the argument he ultimately makes about politics and politicians is that they’re infinitely scuzzier than the boobs ‘n’ blood exploitation movie-within-a-movie Blow Out opens on. (For that matter they’re scuzzier than most of De Palma’s pictures, too.)

George McRyan, the Pennsylvania governor and presidential hopeful the audience learns about on a TV news broadcast, isn’t identified explicitly as either Democratic or Republican. Liberal viewers may interpret McRyan who, based on polling appears poised to win the general election in a landslide, as liberal due not only to his broad popularity compared to the movie’s sitting president, but where his popularity gets him: Lifeless on a hospital gurney. Republican viewers might assume the opposite.

Standing between them and on the opposite side of Blow Out’s lens, De Palma doesn’t give one solid damn. He’s not interested in his conspiracy thriller’s politics, not directly anyway. He’s interested in making Blow Out’s life into an imitation of art, and telling a story about the vast individual components of filmmaking that, when brought together, find the film’s sum. Movies are made of more than scripts and actors and fancy camera angles. They’re made of noise, too.

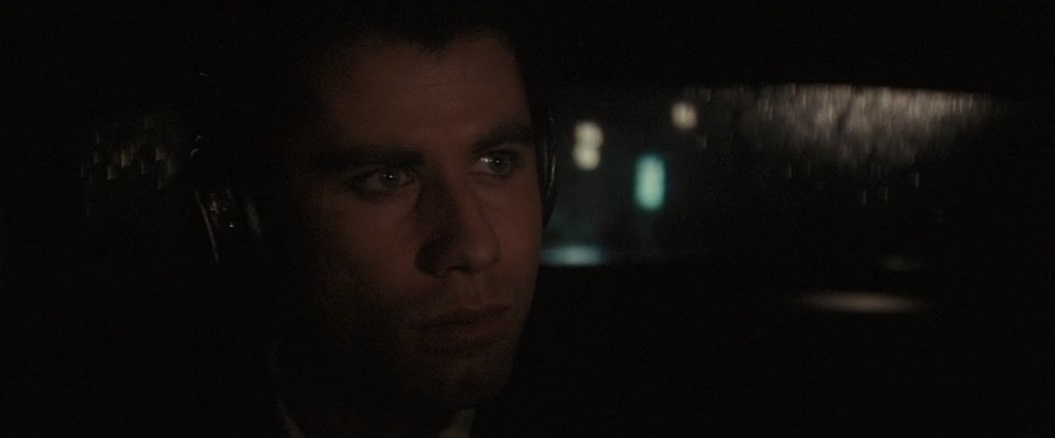

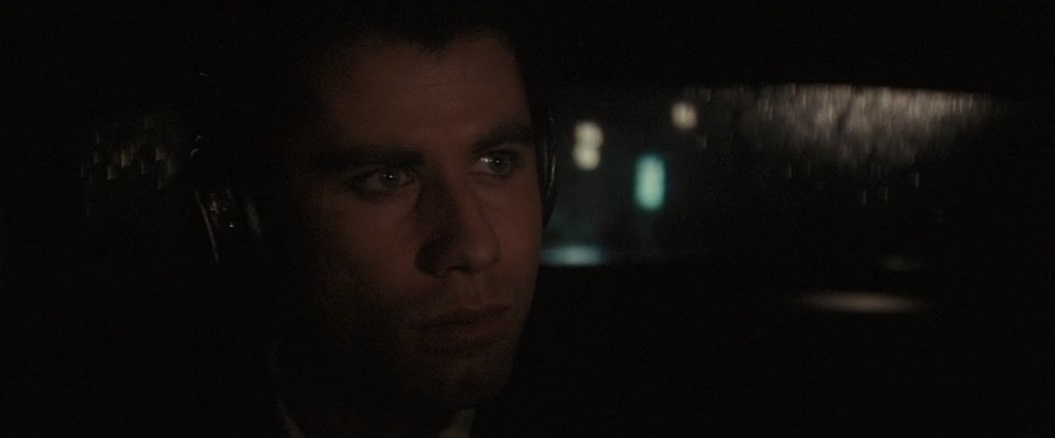

Jack Terry (John Travolta), De Palma’s laid back sound tech protagonist, engages noise in his work and in the world surrounding him. It’s a passion. He stands at tranquil ease on the Wissahickon Bridge, scanning the area for new aural wonders to capture with his Nagra recorder, waving his mic around like a magic wand as if he’s a wizard and his gadget is the source of his arcane power. A contingent of cinephiles today think of De Palma only as a smut purveyor, and while they’re not wrong, exactly, that read is narrow verging on oversimplified. De Palma likes his sleaze. He also likes cinema as art. He’s in many ways the ultimate cinephile, someone born to make movies and who understands how movies speak to an audience. In Blow Out, he demonstrates that understanding within and without the frame: Calling this his best film is an easy layup, but it’s quite possibly true, and if not then it’s certainly his best display of bravura.

Do you like split diopters? Do you enjoy seeing an entire image in deep focus, such that the foreground and background become a single balanced entity? If that’s your thing, you’ll lose your mind when Jack records an owl’s hoot and De Palma fills half the frame with Travolta and the Nagra, and the other with the noble nocturnal bird of prey staring down the viewer up close, contempt blazing in its eyes. When Burke (John Lithgow), the remorseless iceman responsible for McRyan’s demise—another candidate hires him to catch McRyan in a compromising position with Sally (Nancy Allen), an escort, but Burke zigs instead of zagging and chooses to kill McRyan instead—stalks a woman he confuses with Sally through a market at night, the camera lands on the dead, lolling stare of a fish on ice. Burke’s hand reaches into the display to seize an ice pick as “Sally” walks through the back door, illuminated in red light.

The pleasure in Blow Out is the naughty thrill De Palma whips up in an artful, skillfully composed shot executed with advanced filmmaking techniques. This is a really dry way of saying that his work looks great, so great in fact that his craftsmanship belies the material’s indecency. These contradictions coexist harmoniously in the same space. It’s a matter of tone. Sleaze can be exquisite. In fact, the higher De Palma aims, the more we appreciate the sleaze as an element with purpose, because the grandeur of Blow Out’s filmmaking imparts on the plot a sense of scale: De Palma swings big, and by swinging big he emphasizes just how small Jack is in the scheme of things. He’s naïve at best, doomed at worst, and at all times a cog in a society run by powerful, unscrupulous men. There’s nothing he can do to stop the machine’s gears from turning, doggedly as he tries.

Deep focus and basic split screens, another of De Palma’s favorite flourishes, function as other ways of seeing in Blow Out. The film shows us Jack’s efforts to save the day and stacks them against the inevitability of his failure. A surface take on De Palma’s aesthetic is that it looks cool, a detail De Palma prizes as highly as sleaze. But the “cool” is an admission of his pessimism. The act of “seeing” he performs throughout Blow Out is the bluntest tool in his belt, intended to hammer home that McRyan’s death is set in motion by the unstoppable wheels of American political intrigue.

In the end, Burke dies. It’s a small victory. Sally dies, too, and that traditional American celebratory lubricant, the fireworks display, bursts overhead as Jack cradles her body in his arms; the explosive exuberance mocks his grief, rubs in his defeat and reminds us in the audience that the deaths of people like Sally—small people, the socially undesirable types on America’s fringes—are inconsequential to the United States’ political designs. George McRyan is dead. A salvo of brocades, mines, Roman candles and tourbillons for George McRyan. Sally Bedina is dead. Who the hell cares? The fireworks tell the myth of how Americans see themselves and how they see their country. Sally’s limp form and Jack’s defeated gaze tell the sordid truth.

It’s a truth only De Palma and the audience recognize. When Blow Out ends, the lie holds. The cover-up stands. Justice is left undone. The only truth left is Sally’s scream, a nerve-shredding wail immortalized by Jack’s recorder. What will immortalize the dead bodies in the aftermath of January 6th, and bodies yet to come, as Democrats struggle in vain to stem Jordan, McCarthy and Clyde’s corrosive falsehoods flooding the account of what really happened at the Capitol that day? Again, Blow Out answers with truth: Nothing that will mean a damn or make a difference to America’s trigger-happy jingoistic spirit. If De Palma’s a cynic, then he’s a cynic behind a masterpiece we can all still relate to.

Peter Sobczynski, RogerEbert.com

I’m a Sound Man: Brian De Palma’s Blow Out at 40In many respects, “Blow Out” is a recapitulation of the various obsessions that had been driving De Palma throughout his entire career. The murder of the governor is obviously meant to evoke memories of the JFK assassination (with a hint of Chappaquiddick thrown into the mix) and Jack’s dogged attempts to expose the vast conspiracy surrounding it to a public that may not ultimately care is reminiscent of Gerrit Graham’s attempts to crack the Kennedy conspiracy in De Palma’s audacious social satire “Greetings” (1968). Beyond that specific plot concept, the film touches on such elements as voyeurism; a cynical take towards contemporary entertainment; modern technology and the dangers that can come from putting one’s faith entirely behind it; and deeply flawed heroes who are struggling to find some kind of redemption and either fail at it or succeed, only to discover that the price to achieve it may ultimately not be worth it. Part of De Palma's genius comes from presenting his narratives in such stylish and striking visual terms that it isn’t until later on that you realize not everything adds up. While the aforementioned “Blow-Up” and “The Conversation” are undeniable inspirations for the film—all three involve emotionally isolated men with a particular skill set that they attempt to utilize when they stumble upon murder plots—De Palma uses such a conceit in "Blow Out" only as a mere leaping-off point for his own unique take on the premise. The resulting screenplay is a bit of a miracle, as it offers a narrative as dense and complex as any that he had done up to that point (or since then), but in a surprisingly graceful and straightforward manner. With "Blow Out," De Palma allows viewers to grasp what's going on without letting them get lost in the labyrinth (except when that's the point, of course) and without any extraneous bits of business. Even the stuff that appears to be extraneous, such as the “Coed Frenzy” opening or a spree of murders of prostitutes, all ends up fitting together in the big picture that De Palma presents with jigsaw precision.

Like practically all of De Palma’s key films, there are a number of elaborately constructed set pieces in "Blow Out" that bring his considerable skills as a visual stylist to the forefront. But unlike some of his other films, such sequences are so perfectly integrated into the storyline they never feel like he's showing off. Obviously, the "Coed Frenzy" opening is a standout that illustrates that while he's perfectly capable of cranking out mindless exercise in violent style—the kind that he has often been accused of making throughout his career—he's no longer interested in such a lack of artistic challenge. There's also the haunting flashback sequence in which Jack recounts his days with the police and the case where everything went wrong, which serves both as a compelling way to fill in his backstory and explain his cold, cynical attitude towards everything, and to allow De Palma to show what he might have made of “Prince of the City,” a project he was scheduled to do even before “Dressed to Kill” but which he lost out on when the producers elected not to wait a year for Robert De Niro’s schedule to clear up and instead gave it to Sidney Lumet. (This sequence, originally devised for De Palma's version, will make you look at De Palma's "Prince of the City" as one of the great unmade movies.)

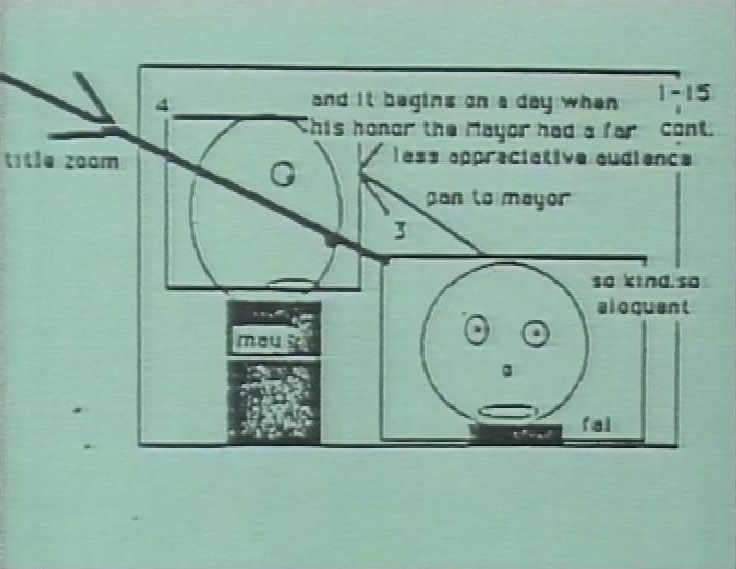

The climactic chase, in which Jack speeds through the crowded streets of Philadelphia (at one point barreling through the middle of a parade) to rescue Sally fro mthe deadly trap that he has inadvertently placed her in, is such a miracle of filmmaking—both in terms of sheer technique and the emotions that it engenders—that Hitchcock himself would have doubtlessly bowed to it out of sheer admiration. (The scene is especially impressive when you realize that De Palma was forced to reshoot it at the last second, after all the footage he shot vanished when the truck carrying it was stolen.) However, the most spellbinding sequence in the film—possibly of De Palma’s entire oeuvre—comes when Jack, using his audio recording and a collection of photographs of the accident published in a magazine a la the Zapruder film, creates a mini-movie that proves once and for all that it was anything but an accident. A scene like this in a contemporary film would be all but unimaginable, and not just because of the massive changes in technology—it has to go on for a while or else it simply doesn’t work. As shown here, it's not only a completely spellbinding exercise in pure cinema but it also serves as beautiful and potent a display of the seductive allure of the filmmaking process as has ever been put up on the screen.

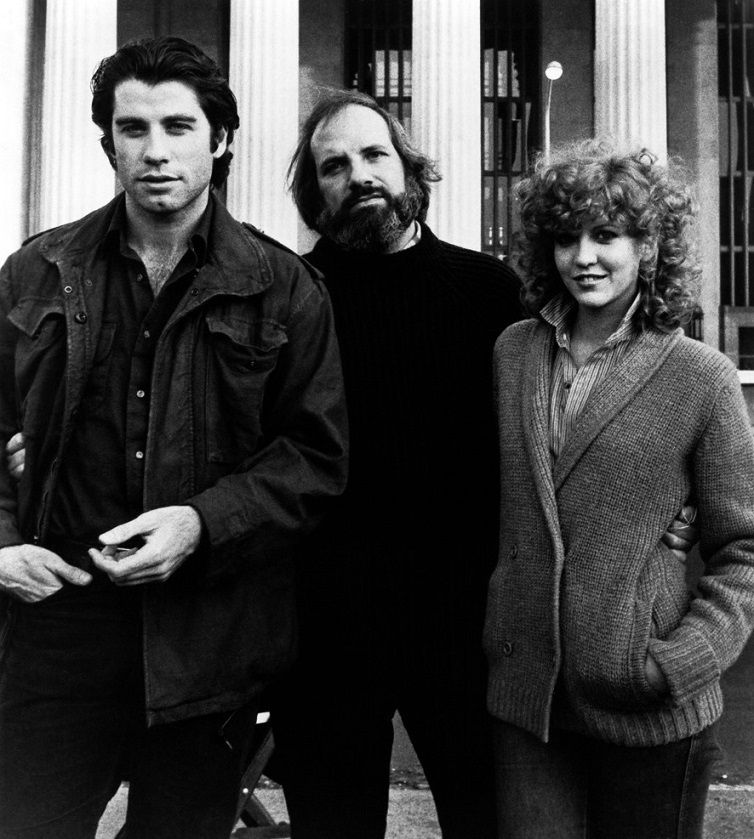

With the major exception of Sissy Spacek's character in “Carrie,” De Palma's characters were oftentimes essentially pawns that he moved around like chess pieces and whom it was sometimes difficult to relate to on an emotional level. Here, the central characters of Jack and Sally are both fleshed out and ultimately engaging despite their flaws, which not only allows viewers to develop an actual rooting interest in them but also gives the finale the overwhelmingly powerful punch that it might not have otherwise produced. Of course, the ability to care about these characters comes in no small part from the truly inspired performances behind them. For example, I don’t think that I am going too far out of line when I suggest that Travolta (who first worked with De Palma and Allen on “Carrie”) has made a number of films that are of a somewhat dubious nature—so many that while the aforementioned “Moment by Moment” was once regarded as a potential career-killer, it probably would not even rank among his ten worst films. However, one thing that you can say about him is that even in the worst and most ill-advised of his projects, you rarely see him simply coasting through a part—even in something like “Battlefield Earth” or “Gotti,” he is always putting in 100% effort. When he puts that approach in the service of a worthy screenplay and role, as is the case here, the results can be extraordinary. Beautifully suppressing the natural charm that helped make him a star but which would have been all wrong here, he plays Jack as a cold fish who has willingly removed himself from the world in order to avoid getting hurt and as he struggles tome the choice to care and reengage once again, he manages to engage viewers without breaking his character. Even though he is a mess, we still root for him and when it all goes wrong, we are just as shattered as he his in the film’s unforgettable final shot. This is by far the finest performance of Travolta’s career—even his turns in “Saturday Night Fever” (1977) and “Pulp Fiction” pale in comparison to it—and one of the biggest tragedies of the eventual failure of the film is that few people saw it at the time are realized what he was capable of doing.

The other key performances in the film are nothing to sneeze at either. When the film came out, there was much criticism that Allen (in what would be the last of the four films she did with De Palma, whom she was married to at the time) was merely playing a downscale version of the high-class sex worker she portrayed so memorably in “Dressed to Kill.” Like so much of the criticism of the film at the time, this observation was not entirely accurate and fails to take into account just how engaging and likable she is in the role—Sally may be a bit naive in certain regards but she is far from being just a mindless bimbo and, as is the case with Jack, we genuinely care about what happens to her during the breathless finale. More importantly, although the film smartly avoids any hint of a conventional romance between Jack and Sally, the onscreen chemistry between the two is off the charts, so much so that one can almost picture them taking those exact same characters and spinning them off into a potentially fascinating romantic comedy.

And since a film of the sort has a tendency to live or die on the strength of their villains, “Blow Out” is blessed with two equally strong performances in the bad guy roles. As the sleazy photographer, Dennis Franz (who had small roles in “The Fury” and “Dressed to Kill”) is an absolute hoot as a guy who suggests what might result if a stained T-shirt suddenly became a sentient life form. John Lithgow, who worked with De Palma on “Obsession” (1976) and would later reunite with him on “Raising Cain” (1992), is a scream of an entirely different and more chilling manner, as someone who suggests a cross between G.Gordon Liddy and the serial killer character that Lithgow would later play so memorably on “Dexter.”

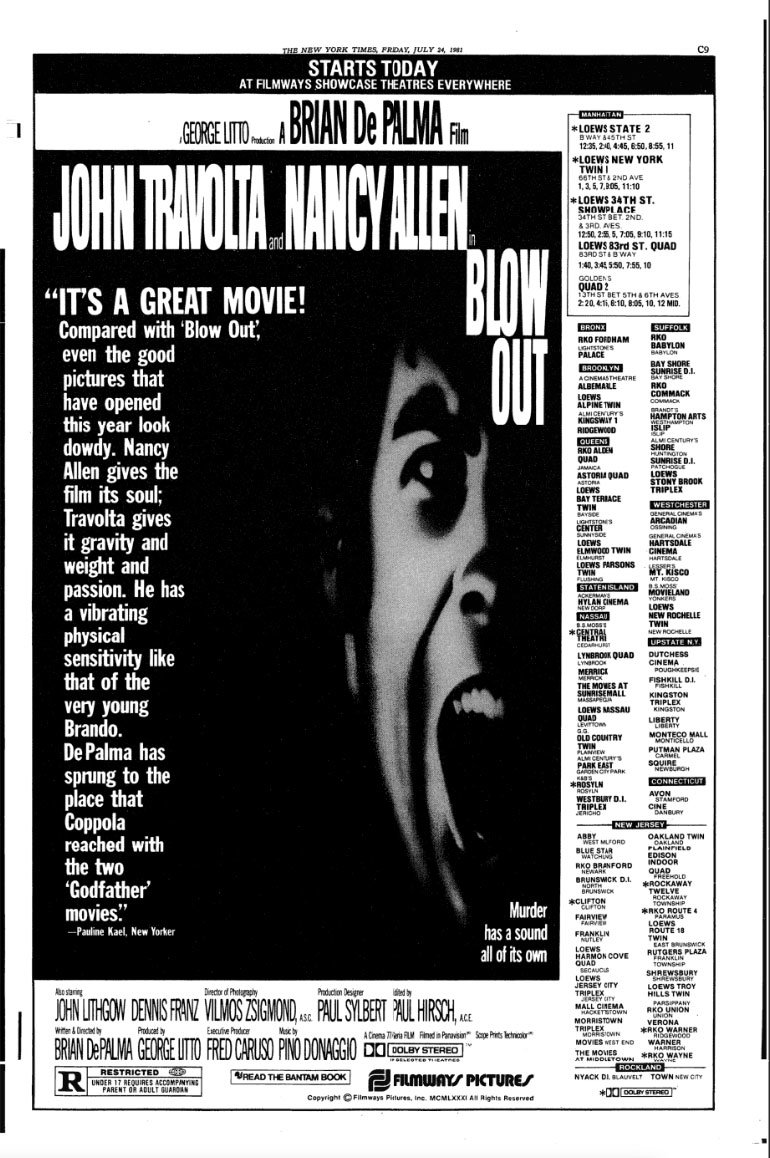

In the wake of the failure of “Blow Out,” De Palma quickly signed on to do the splashy, big-budget remake of “Scarface” (1983). He continued with a career that would continue to raise the hackles of critics and audiences alike while hitting upon the occasional success with films like “The Untouchables” (1987) and “Mission: Impossible” (1996) that allowed him to channel his undiminished filmmaking skills into a more commercially viable framework. The one downside is that, with the exceptions of the war dramas “Casualties of War” (1989) and “Redacted” (2007), De Palma never really tackled material as serious-minded again, even though he proved himself more than capable of with it.

And yet, the reputation of "Blow Out" has continued to grow in the 40 years since it first came out. While the technological aspects have certainly changed, the story has not aged at all—in an era in which people are more willing than ever to find conspiracy in everything, it now feels more in sync with the times than ever before and even the infamous finale feels like less of a shock. It remains a work of stunning cinematic craft from one of our greatest, if too often undervalued, filmmakers and while he has made any number of other great movies over the years, this is the one he deserves to be remembered for above all.