"A MOVIE THAT'S EVEN MORE RELEVANT TODAY THAN WHEN IT WAS FIRST RELEASED 40 YEARS AGO," WRITES DANIEL KURLAND

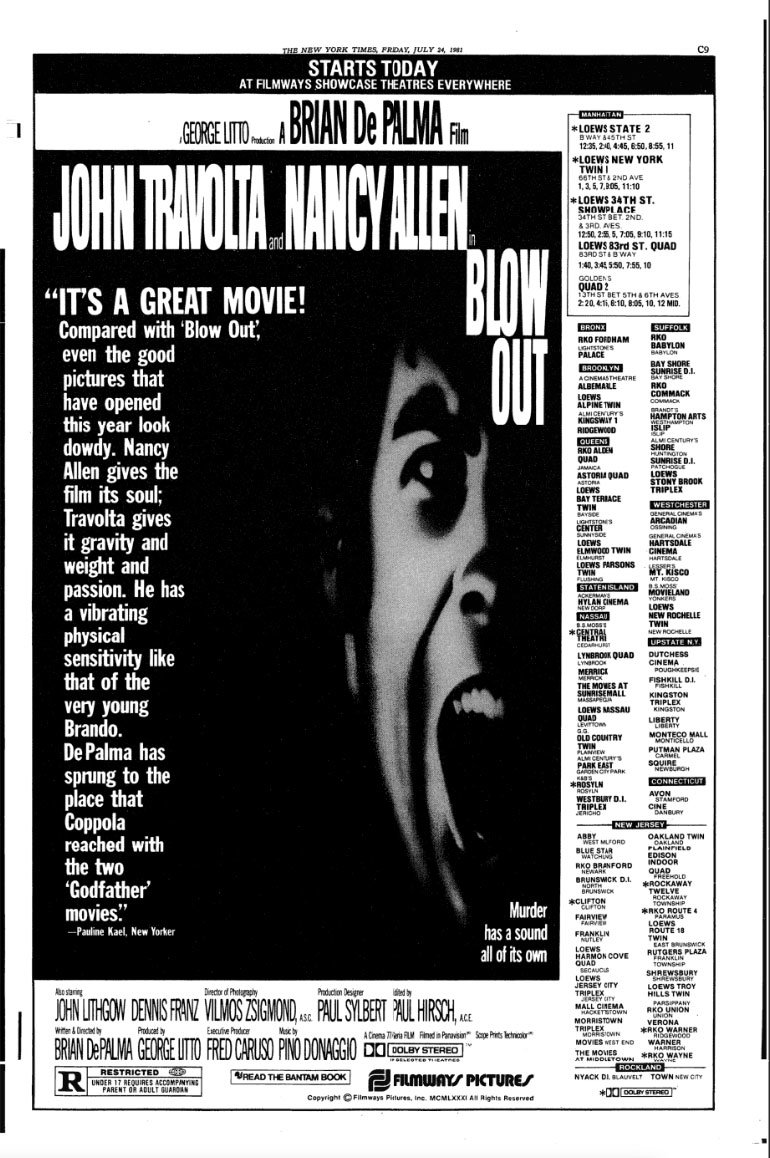

At Bloody Disgusting, Daniel Kurland has posted an editorial about Brian De Palma's Blow Out, "Still a Scream 40 Years Later!"

Blow Out is a movie full of contradictions, not unlike conspiracy theories, which actually manage to strengthen the text. The movie contains contrasting tones that compete against each other for supremacy. Blow Out notably begins with its careful exploitation of the audience. The masterful opening POV sequence occasionally has a moody “killer theme” that turns up on the soundtrack during the slasher’s violent acts, which increasingly overpowers the playful party music playing in the dorm unsuspecting students inside have no idea that they’re in danger. Just like how the music does this, the visuals also create this odd dissonance as the audience tries to figure out what’s going on until they finally realize that this introduction is a ruse and part of the artifice that’s inside of Blow Out, rather than Blow Out itself. It’s the first scene in the movie and also the first time in the film that the audience is forced to reckon with this while Blow Out continually toys with what is reality, what is art, and where the two overlap.It’s all a lie.

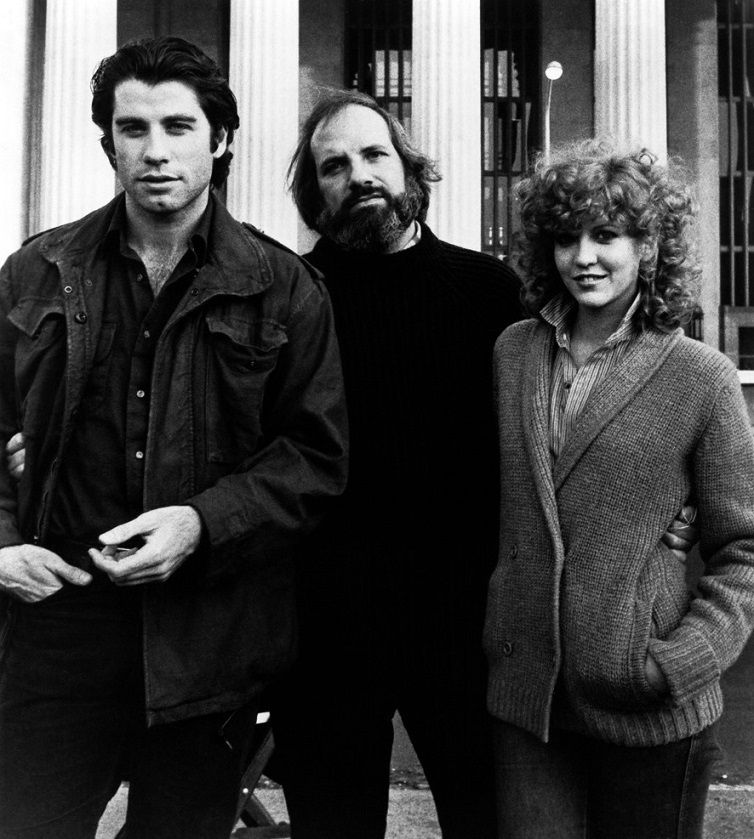

To go one step deeper, Garrett Brown, the creator of the Steadicam, was well-practiced with the equipment after his work on The Shining, but this piece in Blow Out is intentionally clumsy because it’s supposed to resemble a low-budget horror movie. It wants to mess with the audience and use the quality of the camerawork to become the first clue that this is actually a movie within the movie. Garrett actually laments that he couldn’t shoot the opening POV sequence properly and was forced to make it look so schlocky, but that’s the magic of this De Palma introduction. It achieves a more technologically advanced and psychologically enriching version of Halloween’s legendary opening sequence and Blow Out’s introduction genuinely helped popularize the use of the Steadicam and showcase its versatility as a filmmaking tool. It’s a sublime pairing between Garrett Brown during the infancy of the Steadicam’s development and Vilmos Zsigmond’s ever-growing talents as a cinematographer.

This illusory artifice that kicks off the movie also bookends Blow Out. Another powerful example of the blurred lines between art and reality is what concludes Jack and Sally’s story. Burke’s assassination plan that takes out Sally is intself based around subterfuge and fabricated panic that’s exactly the type of scheme that conspiracy theorists would develop. On a deeper level, Sally’s screams of terror fail to be heard and she’s unable to receive help because displays of riotous Americana literally drown her out; whether it’s the noise of the fireworks, the public cheering, or the celebratory music. Her corpse basks in the glow of red, white, and blue lights.

The one time that Jack needs to hear Sally’s scream, he can’t, and it’s what costs her her life. It’s devastating, but even harsher of a blow because of Jack’s aural life and how important listening is to him. It’s a horrifying reality about how the dangers of patriotism can strangle America and bury what’s important, which is relevant then, but even more frightening now with how the news and social media can filter out what doesn’t fit their narrative and highlight America’s benign successes. Pro-America messages can overpower what’s really important and strangle the cries for help in a figurative sense, just like Blow Out literally does, and it was made forty years ago.

Brian De Palma gets so many good and chilling performances out of John Lithgow, but his villain in Blow Out, the mysterious Burke (who’s based on G. Gordon Liddy to some degree), is seriously some of the actor’s strongest work. Burke’s appearances here are incredibly brief, but Lithgow makes every second count. Lithgow’s performance as Burke is also a fantastic example of how the weight and intensity behind a villain can mount through their actions, even when they’re not physically being seen on the screen, so that when they finally do show up it’s deeply cathartic. It becomes the satisfying culmination of all of these sinister machinations up until this point. The camera moves with precision during Burke’s calculated murders in contrast to the klutzy maneuvers from “Co-Ed Frenzy.” De Palma uses the language of this cinematography to communicate that Burke is the real deal and someone to worry over.

Burke’s plan is so needlessly more morbid than it needs to be, but this also speaks to its dark brilliance. His target is only Sally, but he proceeds to kill many women who look like her so that her eventual death is misconstrued as the work of a serial killer’s motive instead of a targeted attack. It’s chilling, but also speaks to how complex conspiracies and actions from political terrorists only highlight how little the public really knows. This kind of stuff can happen underneath everyone’s noses with nobody having any idea because of its stealth and invasive nature.

So many De Palma movies about men trying to unsuccessfully save women–perhaps harkening back to De Palma’s own childhood and his sleuthing efforts to videotape his father’s affairs to protect his mother in the process–but Blow Out presents one of the starkest and nihilistic versions of this idea wherein Jack doesn’t only fail to save Sally, but her death and his defeat are forever immortalized on celluloid to entertain millions of audience members. No one can rewind the footage to change Sally’s fate like in “Co-Ed Frenzy.” It’s the grim irony of this theme that recurs throughout De Palma’s works, especially for a filmmaker who so often uses cinema as the ultimate expression of the soul.

This tragic ending comes as such a blow and feels very much representative of the decisions that happen in movies forty years ago versus today. Emotionally, Jack’s final embrace with Sally is a lot to take in, but De Palma also guarantees that it’s just as visually expressive. What follows is one of the most cinematic moments that’s ever been committed to film. The sheer extravagance of the exploding fireworks as Pino Donaggio’s score swells and Travolta loses himself in Jack’s sadness is just a masterpiece. Whether it’s intentional or not, the galaxy of light that’s cast over the dorm room from an illuminated disco ball during Blow Out’s opening scene also works as a visual counterpoint to these fireworks that works as another element that bookends the movie, both through reality and the illusion of cinema.

Let’s talk about De Palma, who thinks in the cinematic language. Think of that rotating shot, the camera looping around as Jack runs around checking his tapes, which have been erased, sounds of film flapping and Jack doing laps like Sisyphus. Think of the split-diopter of Lithgow’s lunatic holding a photograph up as he descends the escalator, of the fish head and the ice pick, the frog and the owl, and the lovers at the bridge. Think of Jack, under the flaming sky of July Fourth fireworks, a patriotic patchwork of red, white, and blue, holding her lifeless body in his arms as the country celebrates its spectacular anniversary.Despite the obviousness of De Palma’s formal skill, Blow Out was initially greeted with indifference, and didn’t get a boost in credibility until Tarantino praised it (it is now rightfully revered, of course). Notably, it stands out in two ways from his other thrillers. He famously has made small movies for himself and big movies for paychecks; this is a small movie made big by a generous budget (by De Palma’s standards, at least). The extra money meant better sets, car chases through parades, many retakes and reshoots, De Palma taking a month off of shooting to think about the script more. And it’s a tragic film, and the tragedy here comes not from pure spectacle, (though there is that, too) but the fact that we care so much about these characters, these performers; we care about Travolta’s doomed-to-fail sound man and Nancy Allan’s doomed-to-die sylph, and when they hurt, we hurt.

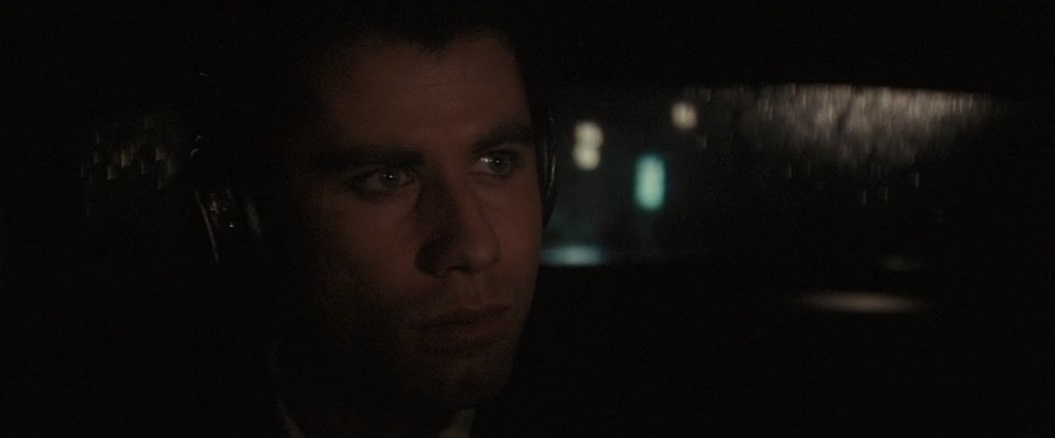

This is a film that begins with a murder and a scream, piteous and irritating, and ends with a murder and a scream, pained, one that reverberates deep in the corridors of the heart. De Palma’s deft manipulations of images and sounds are redoubtable, but much of the film’s pure emotional power comes from Travolta’s performance, the sincerity he brings to this tragic would-be hero who, in solving the mystery, in getting the answers he seeks, ends up in his own personal hell, his greatest failure turned into a throwaway shriek coming from another woman’s mouth.

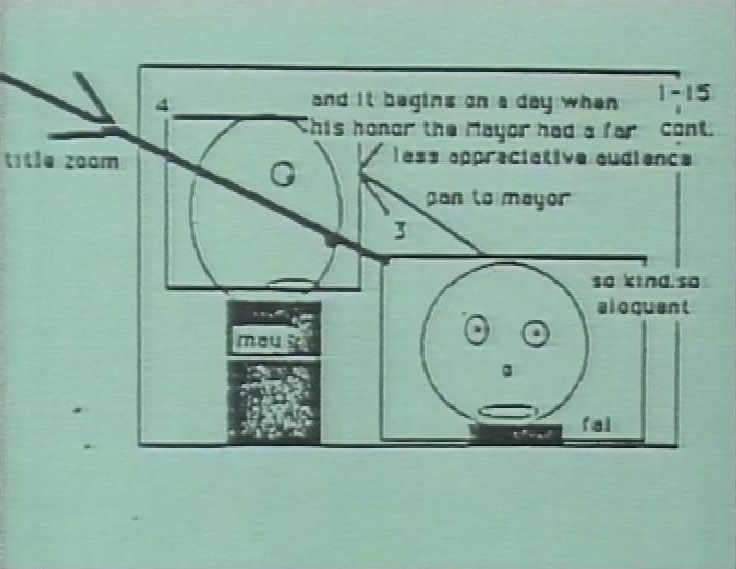

The sound recording sequence is a joy – here we just luxuriate in the art of movie-making. Jack is out by the river, underneath a bridge, recording the natural sounds that he will end up using in the movie – first we hear the sound, then we follow Jack’s mic as it picks up on it, and then we see the source – a frog, a couple having a quiet talk (unlike the chat between the couple in The Conversation, this one’s absolutely harmless), an owl….and something we don’t see the source of – a strange buzzing, winding sound. What the hell is that? We soon find out that it’s Burke pulling and releasing the garrote on his wristband. One of Blow Out‘s main pleasures is giving us little clues and hints that only become truly apparent on a second viewing. It’s not the sort of thing that makes a first watch baffling, just the odd lovely touch that makes further viewings even more satisfying.This key sequence will be revisited many times throughout the movie – Jack will pore over his recording to try and work out what happened, and we the viewer are granted visual reminders of the action. This is taken a step further when Jack acquires a series of still images of the event, taken by Sally’s opportunist sidekick Manny (a scuzzy Dennis Franz). Jack cuts out the images, photographs them and creates a mini-movie to accompany the sound, and it’s essentially like watching a movie being made before our very eyes. De Palma is a classic visual storyteller, and these sequences showcase that love of craft and creation beautifully.

Throughout Blow Out, De Palma deploys his box of tricks superbly to the plot – in addition to split-screen we have his much-loved use of deep focus, as well as long-takes, 360 degree spin-arounds and back-projection. Like with Dressed to Kill, De Palma’s execution of cinematic technique is so kaleidoscopic it makes most other directors works feel awfully monochrome. The substance and the style of his films complement each other to such flawless degrees that his methods are precisely what makes the drama so dramatic. This isn’t just fancy dressing. This is cinematic style at its absolute peak. There’s also another wonderful score by Pino Donaggio. Okay, so his occasional lapses into what I can only describe as the imagined lost incidental music for some cancelled detective show may sound a little dated now, but the main orchestral and piano themes, especially the ones centred around Sally, are absolutely heartbreaking and truly beautiful.

Adam Nayman on Neo-Noir, Criterion Current

Where film noir gained potency from its distorted yet crystalline reflections of a starkly stratified, economically depressed society—a world of detours down nightmare alleys at nightfall—neonoir applied a carefully filigreed lens of nostalgia, aligning it with the returns to western and gangster-movie forms that served as the foundations of the New Hollywood. The eagerness with which writers seized upon and venerated movies like Robert Altman’s The Long Goodbye (1973) and Roman Polanski’s Chinatown (1974)—one a melancholically modernized Raymond Chandler adaptation, the other a sadistic riff on the author’s knight-errant narratives in which the windmills prove un-tiltable—had as much to do with retrospectively elevating their directors’ underlying inspirations as acknowledging their state-of-the-art craft and state-of-the-union cynicism.While the Coens probably prefer The Long Goodbye—they quoted it affectionately in both the Chandler-happy The Big Lebowski (1998) and the non-noirish Inside Llewyn Davis (2013)—it’s Chinatown that feels like neonoir’s early-seventies epicenter, an elegant, scarifying return to the primal scene of Los Angeles in the 1930s. The film’s throwback setting and aesthetics barely belied screenwriter Robert Towne’s post-Watergate cautionary fable about the intersection of establishment political power and patriarchal perversion, both monstrously conjoined in John Huston’s businessman Noah Cross and perceived—perceptively but futilely—by Jack Nicholson’s nosy investigator Jake Gittes, who recognizes the older man’s crimes against city and family alike and can do nothing to stop them. As novelist and screenwriter R. D. Heath writes, “instead of vice being the property of outsiders, drifters, slum-dwellers or dead-eyed suburban losers and predators, [in Chinatown] it flows directly from the most respectable man in town, who aims to be even more respectable . . . the future shall venerate Noah Cross’ name and regard him as a founding father.” When Faye Dunaway’s doomed and diminished Evelyn Mulwray—fated to be both Cassandra and Elektra in the movie’s neo-Grecian schema—cries out of her demonic pater “he owns the police,” the actress’s emphasis on the second word is chilling. It evokes how both individuals and institutions can be held as property, and the image of Huston enfolding his wide-eyed, open-mouthed daughter-slash-granddaughter (Belinda Palmer) is as predatory and unsettling as anything in American cinema. It lays bare a hopelessness that doesn’t feel safely contained by the parameters of the story or the screen, as ancient as the forces coursing through a horror movie like William Friedkin’s The Exorcist (1973), an enduring evil loosed once more upon a fallen world.

Arthur Penn’s Night Moves (1975) revolves around a smuggled sculpture that exists on a continuum somewhere between The Exorcist’s excavated Assyrian totem and the Maltese Falcon: a valuable, cursed antique that turns out to be the stuff that nightmares are made of. Like Chinatown, Penn’s film is a neonoir scribbled in indelible ink, with a cloud of encroaching blackness gradually blotting out the sky on both coasts. There’s a determinedly panoramic sprawl to Alan Sharp’s screenplay, which keeps shifting the action back and forth from gleaming, sun-blind Los Angeles—the prowling grounds for Gene Hackman’s hamstrung football-star turned PI Harry Moseby, a laconic brother shamus to Jake Gittes and Philip Marlowe—to a swampy outcropping of the Florida Keys, where a jailbait heiress has absconded to either visit her stepfather or seduce her mothers’ other lovers . . . or both. Incest remains at the level of subtext (“the world is getting smaller, the kids are getting younger, and I’m getting drunk”), but corruption, coercion, and subterfuge ooze from the story’s every pore.

Penn’s chosen style is much slower and more deliberate than Howard Hawks’s serene velocity in The Big Sleep (1946)—and some shots hold long enough to “watch paint dry,” as per Harry’s priceless, tossed-off critique of/stealth encomium to Eric Rohmer—but it cultivates a similar sense of perpetual, in media res confusion, of endlessly unfolding exposition that explains everything except what’s actually going on. A half-decade before Blow Out (1981), Penn wrings a sinister variation on the Zapruder film via footage of a movie-set car crash that suggests not only an act of behind-the-scenes sabotage claiming the life of a supporting character, but, more widely, a booby-trapped reality. The bloody coup de grâce, meanwhile, is delivered by another, larger vehicle, a horrific act of death from above as the MacGuffin disappears beneath the waves, as lost to the ages as the treasure of the Sierra Madre or all those crisp bills scattered to the wind at the end of The Killing (1956).

Both Chinatown and Night Moves make a determined show of trailing off, of punctuating tragic revelations with slippery ellipses, the former through a wobbly tracking shot that loses sight of its subject, the latter in a long view of a damaged boat tracing figure eights along the ocean’s surface into infinity. Without closure, there can be no catharsis, but some of the strongest neonoirs of the early eighties take a less open-ended approach; they lock into place like iron maidens around their hapless protagonists, fine-tuned mechanisms in an era of high-concept studio engineering. It’s telling that Steven Spielberg and George Lucas’s right-hand man Lawrence Kasdan, the cowriter of The Empire Strikes Back (1980) and Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), was keen to try his hand at another old-school homage, and also that he tried to reinject some of the sexiness that had become neutered in the surrounding blockbuster deluge. In Body Heat (1981)—set, like Night Moves, in Florida mid-heat-wave—William Hurt’s inept lawyer gets warned about “following his dick into a very big hassle.” He ends up in jail for a murder he didn’t commit in lieu of the one he did (a comeuppance copped by the Coens for The Man Who Wasn’t There); meanwhile, confidence woman Kathleen Turner fulfills her high-school-yearbook ambition to “be rich and live in an exotic land.”

Kasdan’s satisfying, putatively progressive girl-on-top scenario deviated significantly from the seventies sacrificial-femme template (and generated reams of academic discourse as a result), while De Palma’s Blow Out ends, much like Chinatown, with the scream of an innocent woman slain on the altar of an upwardly mobile (and spiderily all-encompassing) conspiracy. There will be no forgetting for John Travolta’s soundman, however: his mythic punishment will be to hear her scream over and over, wrecking his own soul on the rocks of the siren’s call; it’s as if De Palma were trying to show Polanski what downbeat really looks like. The one rousing semi-exception to 1981’s roundelay of unhappy endings—a movie with catharsis to burn—is Ivan Passer’s Santa-Barbara-set Cutter’s Way, about a paranoid, disabled Vietnam vet played by John Heard who takes arms against a sea of troubles—and aim at a monstrous, all-consuming local tycoon—by briefly adopting the iconography of the old West. Cutter doesn’t survive his brief, glorious bout of John Wayne cosplay, but his best pal, Bone (Jeff Bridges), shows true grit by pulling the trigger in his stead—a replay of the ending of The Long Goodbye torqued more toward cosmic justice than individual retribution.

Updated: Wednesday, July 28, 2021 7:45 AM CDT

Post Comment | Permalink | Share This Post