"A POST-COLD WAR DECONSTRUCTION OF THE '60s"

As Brian De Palma's Mission: Impossible turns 25 later this year, A. J. Black over at 25YL considers the film as one that feels "both uniquely rooted in the 1990s and decidedly out of time."

Though it isn’t really until 2015’s Rogue Nation that Mission: Impossible directly begins to question the validity of the IMF in the modern day—much like Skyfall does with the 00 section—De Palma lays the foundations of exploring whether a concept so rooted in the Cold War showmanship, theatrics and game theory as Mission: Impossible can even exist in a world that doesn’t need it. Rogue Nation’s answer, further underlined in Fallout (which more than any of the previous films attempts to capture some of the essence of De Palma’s movie, even if aesthetically it has more in common with Christopher Nolan), is that the IMF *is* still relevant, but for one reason, and it’s the same reason as with the 00 section: in that franchise’s case, it’s James Bond. In Mission: Impossible’s case, it is Ethan Hunt.Mission: Impossible does not sell Ethan, however, as a Bond proxy. Cruise’s charm is perfectly evident but Ethan is not a seductive, one-man killing machine, or indeed the death-defying nihilist he becomes post-MI:3. Ethan here is a touch more enigmatic and distant, which befits the colder stylings of De Palma’s approach to the material. His lens channels Hitchcock while imbuing the frame with a distinctly De Palma-level of paranoia. Behind the 90’s action beats and slicker dynamic, there remains a visible 70s conspiracy aspect to Mission: Impossible which is missing from subsequent pictures. It’s as if De Palma didn’t believe in the 60’s show, or didn’t believe it could exist beyond the 60s, and intentionally tries to revive the property within a post-70s culture, one where spooks like Kittredge reflect a government far more willing to sacrifice the lives of spies such as the IMF as part of a bigger, self-interested picture.

You only have to look at the strange character of Claire Phelps to see how Mission: Impossible doesn’t follow a traditional narrative pattern, particularly for a character like Ethan. MI:2, in trying to recast him as an American folk hero spy, immediately gives him ‘the love interest’ who you know will be disposable by the end of the picture (which turns out to be the case), but De Palma never tips Ethan and Claire into any kind of conventional romance. There is sexual chemistry and clear frisson, which almost enters into sexually aggressive territory at one point, but there is only the suggestion that Ethan and Claire may have slept together, and that Ethan may have compromised his own morals in doing so. Yet, in much the way Ethan becomes a tactical master three steps ahead of his enemies, sleeping with Claire may have been part of his plan all along, when ostensibly it seems to be part of Phelps’.

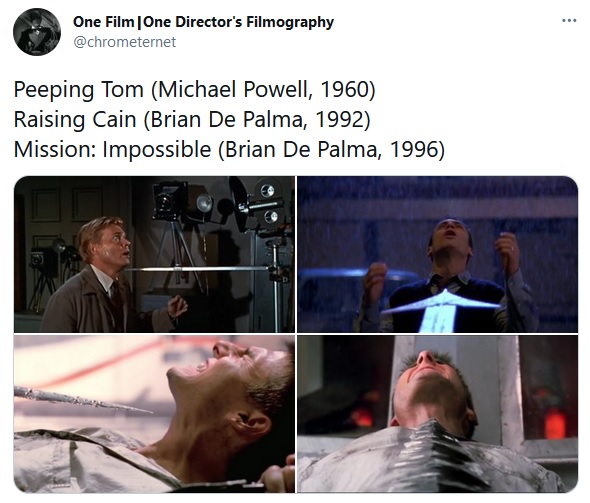

Claire, played by beguiling French beauty Emmanuelle Beart, is a strangely inert character. She is a spy yet does not seem to have any real agency about her. She is married to Jim yet this almost feels like a technicality, given we see almost no sign of warmth or connection between them. She might or might not have been complicit in murdering the IMF team; during the beautifully executed scene in which Phelps reveals his guilt to the audience yet not directly to Ethan, but which can equally be read as Ethan figuring out that Phelps is Job, Ethan actively imagines and then discounts Claire as the one who blew up team member Hannah’s car. If Ethan does have feelings for Claire, this could be his way of refusing to countenance she could be a traitor\killer, and him trying to protect her, but De Palma keeps it ambiguous. We never quite know for sure, come the end, if Claire was always just in it for the money like her husband. She is also never really defined as a rounded character in her own right.

Phelps certainly seems to believe Ethan slept with his wife and made that connection, given how in their final confrontation he quotes the Bible and the well-known passage: “thou shalt not covet thy neighbour’s wife.” This plays into the odd level of religious symbolism which underlines Phelps’ extremism; he presents himself to Max as Job 3:14, which the CIA believe is code for an operation but Ethan figures out is the following Biblical passage: “with kings and counsellors of the earth, who built for themselves places now lying in ruins.”

This suggests Phelps is or was a religious man (and given Voight’s own personal leanings, very possibly a conservative), particularly in how he seems to be using Christian scripture to justify the betrayal of his nation. ‘Building for themselves’ references his own attempts to become a mercenary and profit over the deaths of many of his fellow spies still protecting their country, while the ‘places now lying in ruins’ could be how Phelps considers America: a country he does not recognise following the end of a career-defining hostility. There is a fundamentalist extremism at play here which, oddly, presages how certain Middle Eastern organisations would twist Islam to fit their own self-aggrandising interpretations as we entered the next decade.

Oddly, though, Redgrave’s Max tells Ethan, when posing as Job, that “Job is not given to quoting scripture in his communications” after Ethan does just that, suggesting Phelps is a false prophet. He doesn’t really know or understand the Bible and it could just be another example of his warped psyche when it comes to America as a nation – using the Christian belief system which underpins the land of the free against it. De Palma doesn’t take these religious notions too much further but McQuarrie certainly revisits them twenty years later in Fallout; Ethan again poses as a terrorist underpinned by quasi-religious doctrine when making deals with Max’s daughter, no less. This is no doubt an intentional homage to the first film but it does show how Mission: Impossible casts a long shadow across the rest of its own franchise.