DAFT PUNK 'EPILOGUE' - 'PHANTOM' - ETC., ETC.

THE VIDEO THEY USED TO ANNOUNCE THEIR SPLIT CONCLUDES WITH PAUL WILLIAMS COLLABORATIONThe video above,

Epilogue, was posted on YouTube this past Monday, effectively announcing the end of

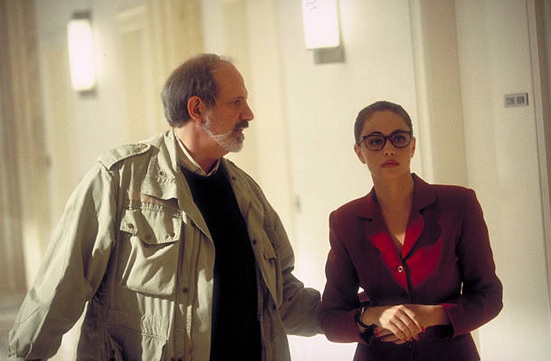

Daft Punk. The video repurposes footage from the duo's 2006 avant-garde science fiction film,

Daft Punk’s Electroma, and is mostly silent, but concludes with the 2013 song "Touch," a collaboration the pair recorded with

Paul Williams. The clip, then, brings to mind not only

Phantom Of The Paradise, but also evokes, quietly, the Antonioni/Pink Floyd conclusion of

Zabriskie Point, and, by extension, the conclusion of

Brian De Palma's

The Fury, albeit with a more somber melancholia than rage.

Ryan Ninesling at The Quietus describes the clip nicely, in an article headlined, "Daft Punk Said Goodbye With The Film Baring Their Soul" --

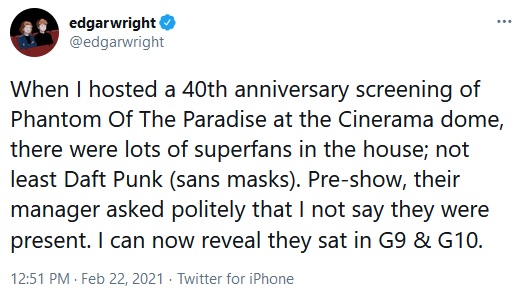

Bangalter and Homem-Christo’s cinephilia formed Electroma into a transformative experience for them, as their love of films was already hardwired into their identities long before the film was even conceived. Much of their music has been described by the pair as a love letter to the memories of films they bonded over in children, principally Brian De Palma’s satirical rock opera Phantom of the Paradise. Two other film projects they’ve worked on – the music video collection DAFT: A Story About Dogs, Androids, Firemen and Tomatoes and Discovery’s extended anime tie-in Interstella 5555: The 5tory of the 5ecret 5tar 5ystem – are steeped in the pair’s seemingly vast knowledge of international cinema and television. DAFT boasts direction from a collection of beloved auteurs ranging from Spike Jonze to Michel Gondry, while Interstella 5555 was born from a collaboration with the pair’s childhood hero Leiji Matsumoto, who has penned innumerable space opera manga and anime. Electroma is unique in that it was the first and only film that was entirely Daft Punk’s own organism; they penned the script, co-directed, and Bangalter served as cinematographer, spending pre-production reading over 200 copies of the filmmaking magazine American Cinematographer to prepare. Electroma is no mere promotional add-on from Human After All; it’s a fully-formed feature with shades of independent cinema running through its circuited veins. The horrific, surreal masks the pair don in order to appear human mimic the nightmarish imagery of David Lynch’s Inland Empire. The robots’ ill-fated journey into the desert mirrors the doomed trip that forms the center of Gus Van Sant’s Gerry. The twisted depictions of suburbia and the otherworldly image of Homem-Christo wandering the wasteland alone evokes the mood of Derek Jarman’s The Garden. Through this confluence of cinematic flourishes, Electroma quietly highlights what Daft Punk’s discography was always trying to: conformity is an ironically surreal prison, and the only way to free ourselves is to let go and feel the music. Otherwise, we self-destruct.

This idea has been cemented by the duo’s use of the film’s climactic scene as a eulogy for their career, with some noticeable tweaks to the original film further emphasising Electroma’s importance to their legacy. The original film ends with Homem-Christo’s lonely robot giving into despair over the death of his silver-domed partner, sealing his own fate by smashing his helmet and using the broken glass to set himself ablaze in the desert sun. The new epilogue now gives the pair a more bittersweet ending, holding on to Homem-Christo walking off into the sunset, the hauntingly beautiful choral section of their Random Access Memories track ‘Touch’ sending him on his way. “Hold on, if love is the answer you’re home” croons over and over as 28 years of history are summarized in a few poignant frames. The newly formed juxtaposition of music and imagery affirms the romantic humanism that runs through these funky robots’ souls, reminding us of their career-long belief that our connections to one another, whether through music or other means, form the basis of our souls. By repurposing Electroma in this way, Daft Punk said goodbye with their motherboards laid bare for all the world to see.

Much will rightfully be written about Daft Punk’s musical output in the coming weeks, but their cinematic output shouldn’t be ignored. Electroma, in particular, offered a gateway to cinematic history beyond the mainstream, putting the duo’s forebears in direct conversation with the contemporary. It crystallised Bangalter and Homem-Christo as great purveyors of the human experience not just through their music, but through every sense of what it means to be alive. They visualised everything they were feeling and subsequently imparted the lessons of that experience to us, as they always graciously did. On the strength of that gift alone, the spirit of Daft Punk will live on forever.

Back in 2013, in a review of

Random Access Memories,

Slate's Geeta Dayal delved into Daft Punk's love for

Phantom Of The Paradise, and the song "Touch" --

Here they’ve “sampled” the vintage production of their favorite records, using the same analog equipment, techniques, and musicians. Instead of sampling Chic, they brought in Chic co-founder Nile Rodgers to play guitar on two tracks. Instead of sampling Quincy Jones’ productions for Michael Jackson in the 1980s, they brought in the actual session musicians who played on the albums—including John J.R. Robinson, a drummer on Michael Jackson’s Off the Wall, and the guitarist Paul Jackson, who played on Thriller. They’ve “sampled” the clothes, too (Daft Punk’s tight sequined jackets resemble Michael Jackson’s) and the fonts (the cursive lettering on the cover of Random Access Memories resembles the cover of Thriller). Daft Punk even “sampled” their favorite movie—the 1974 Brian De Palma schlock classic Phantom of the Paradise—by inviting in Paul Williams, the movie’s composer and lead actor, to sing the album’s epic, melodramatic centerpiece, “Touch.” Phantom of the Paradise is key to understanding Daft Punk’s aesthetic. In the movie, a nerdy songwriter is reborn as a phantom who attempts to exact revenge on an evil svengali record producer named Swan. In one scene in the movie, Swan traps the phantom—now wearing a tight black leather jacket and a robot helmet—in a sophisticated recording studio walled with racks of analog gear. The phantom, whose vocal cords have been destroyed, speaks through a talk box attached to his chest, sounding remarkably like a vocodered lyric in a Daft Punk song.

It’s easy to see why the rock opera was catnip for Daft Punk, who claim to have watched it more than 20 times—the movie is completely over-the-top, drenched in pathos, and layered with in-jokes and sideways references, much like the band’s music. Daft Punk’s black leather outfits in their 2006 feature film, Electroma, seemed inspired by the phantom. “Electroma is a combination of all the movies we like, paying a big, almost unconscious homage to them,” de Homem-Christo told Stop Smiling in 2008. “There are so many different influences: In the end, it becomes such a melting pot of everything that it resembles something else altogether. We love cinema the same way we do music—we’re from a generation that doesn’t segregate.”

“Touch” is the apex of Random Access Memories, the total realization of the album’s ambitious reach. There’s nothing cool about it, and it takes guts to make music like this in 2013 on such a grand scale. It’s Daft Punk’s love letter to Phantom of the Paradise, and it’s schmaltzy and deeply weird. The lyrics are, well, daft (“Touch, sweet touch/ You’ve given me too much to feel”), but the lyrics are beside the point; Williams’ graceful vocal delivery is awe-inspiring. It’s simultaneously melancholy and uplifting; the moment where Williams’ voice trails off and “Get Lucky” begins is a great moment in pop music.

Vulture's Craig Jenkins also touches on the layers of meaning in "Touch" --

The mini-opera “Touch” may seem indulgent, but remember that the robots got the idea for masks watching Paul Williams in Brian De Palma’s outrageous 1974 musical Phantom of the Paradise. Was Daft Punk this molting, unpredictable, ever-changing thing, or was it more like an operating system whose day-to-day mechanics progressed through the years but always in service to a steady and unchanging core mission?