EDITED BY LUIS AZEVEDO, BEAUTIFULLY COVERS ENTIRE CAREER IN 4 MINUTES

Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | May 2020 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | |||||

| 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

| 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 |

| 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 |

| 31 | ||||||

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

Anderson notes that Dmitri’s (Adrien Brody) walk down the hotel hall feels inspired by Brian De Palma. “We were talking earlier about Brian De Palma,” he adds a beat later.

This week, Alec Baldwin's Here's the Thing podcast features last October's on-stage conversation with Brian De Palma at the Hamptons International Film Festival. Baldwin provides an intro to the episode:

This week, Alec Baldwin's Here's the Thing podcast features last October's on-stage conversation with Brian De Palma at the Hamptons International Film Festival. Baldwin provides an intro to the episode:The Untouchables, Casualties of War, The Bonfire Of The Vanities, Raising Cain, Carlito's Way, Mission: Impossible... Brian De Palma didn't just make all those movies, he made all those movies... in a row. Nobody balances suspense, action, and character better than he does. Each film is a master class in building tension, with tracking shots, disconcerting angles, and split screens. And then he releases that tension with the blunt shock of violence. In any De Palma film, the camera is ultimately the star. De Palma is the son of a surgeon, and he went to Columbia for physics. But he quickly discovered where his true passion lay. You know him as a virtuosic movie director, but before that, he was a fixture of the experimental Greenwich Village movie scene of the 1960s. That's where he cast a then-unknown actor named Bobby De Niro. Fitting, since De Palma later became known for working with all the greatest actors. His very first Hollywood movie starred Orson Welles. Last summer, the Hamptons International Film Festival gave Brian De Palma the Lifetime Achievement Award. I was honored to speak with him in front of a live audience when he came to accept it.

De Palma responds: "This is a long funny story. I was head of the Columbia players. And the Varsity Show is a very big thing at Columbia. So there were two shows up to be voted for. And I was just an apprentice that was going to take over the Columbia Players the following year. So, in these situations, everybody's, you know, got their own sort of corrupt intent, because, if you do my play, I get to play the lead, and you get to direct, da da da. I knew nothing about this. There were two really good scripts. One by Steve Rossen, who was one of my school mates at Columbia, and the other one by Terry McNally, a very funny comedy." [A Columbia College obit of McNally, who passed away earlier this year, notes that "McNally wrote the 66th Annual Varsity Show, The Streets of New York, in 1958."] "And they fought for hours, and they were deadlocked, you know, like six-to-six, and it was getting late, and it was about midnight, and they said, they looked over to me, because I had read both scripts, and they said, well, let the kid decide. So I said, well, I think that Terry McNally's script is funny, let's do that one. 'Great!' Everybody leaves.

"That night, I was shooting my first short, which consisted of Pan coming out of the tunnel at 116th Street. I was not the director, I was just author and cinematographer. I get to the location and my director arrives, Gene Marner, I'll never forget his name. And he comes with his very Sicilian girlfriend named Charley. And she comes over to me, and she says, 'You fucking idiot! You didn't vote for the Rossen play? Didn't you know that Gene was going to direct it?' And I go, 'Huh?' [Baldwin laughs] And then they walked off. And they took the lead actor with them. So here I am, at 116th Street, at three in the morning, staring into an empty tunnel, saying, 'I'm gonna direct this now.'

Baldwin: "And that's it."

De Palma: "That's it."

Baldwin: "And you found some waitress at an all-night diner and said, 'Come with me, you're my lead!' You didn't need any actress for the shot?"

De Palma: "No, I had to go out and find my own actors and start all over again."

""It's a five-week programming event with epic films, iconic stars, and brilliant stories that viewers love—and love to watch together," CBS programming exec Noriko Kelley states in the CBS press release. CBS also put together a retro-fashioned promo commercial that can be watched on its Facebook page.

"All hail the return of CBS ‘Sunday Night at the Movies’ in May," reads a San Francisco Chronicle headline from this past week. Forbes' Scott Mendelson expects that a new commercial for Paramount's upcoming Tom Cruise-starring Top Gun: Maverick will air during the Mission: Impossible slot May 17th. At The Stranger, Bobby Roberts writes:

It's so bizarre to see the CBS Sunday Night Movie come back to brodcast TV after being made more-or-less obsolete by cable back in the '90s. And then cable was made obsolete in the '00s by the internet, and now because the movie industry doesn't know what it's going to be in the near future, media companies like Viacom/CBS are looking at all these watch parties, looking at their network programming, noticing their large back catalogs, and boom: The Sunday Night Movie returns with a slightly different name at 8pm tonight, presenting a perfect excuse for everyone to get together at the same time, in the same place, and watch 1981's Raiders of the Lost Ark, maybe the most perfectly constructed film in cinema history. Maybe. I’m sure someone out there has an argument on deck, but I’m betting their champion of choice doesn’t include a giant pit of snakes; a fight inside, on top of, and hanging off the front of a truck at 50 mph; a holy box that melts Nazi faces like Totino’s Party Pizza; and—most importantly—the presence of peak Harrison Ford in all his sweaty, smirky, silly-yet-sexy glory.

Jim Jarmusch's Dead Man gets the top spot on this list.

"Shot on high quality digital and downgraded through analogue processes to give the appearance of VHS," writes The Movie Waffler's Eric Hillis, "She’s Allergic to Cats is a movie that seems determined to alienate as many viewers as possible from the off. Its eventual audience will likely be small enough to fit in its protagonist’s cramped apartment, but give yourself over to its grimy aesthetic and absurdist humour and you’ll find it a charming piece of punk filmmaking. You might even find some of its lo-fi images quite beautiful, and if nothing else, its recreation of the Carrie prom scene with a bewildered tiara-clad tabby is worth the rental price alone."

Update: I watched the free screening tonight, enjoyed it very much. In the chat alongside the movie, Reich mentions that the version screened tonight at Twitch was the original cut ("slightly different" than the version streaming on iTunes and Amazon Prime). He said part of the reason the movie is being released in 2020 instead of in 2017 is because he had to change some of the songs he had used in the original cut due to issues in getting the rights. He also mentioned that the dog who plays Karma in the film was Sonja Kinksi's real dog, Audrey, who has since passed away. Reich is now working on a Christmas-themed horror movie.

Here are two of the four split-diopter frames from The War Of The Roses that were posted by Crítico Cítrico:

Richard Brody, The New Yorker:

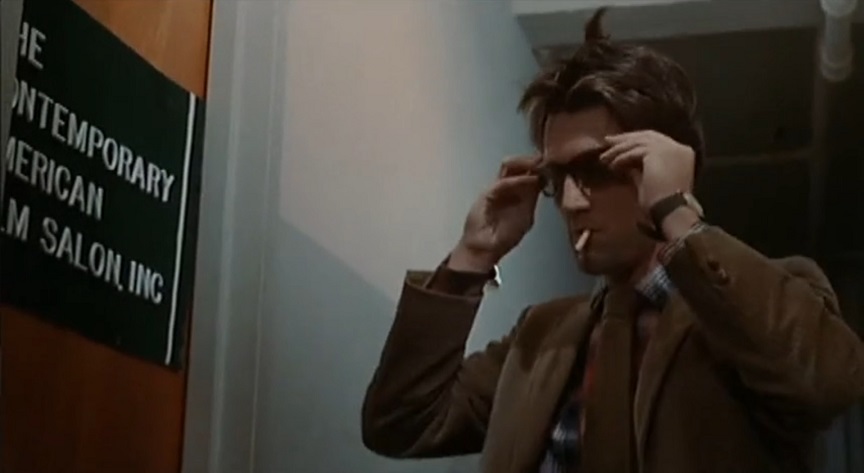

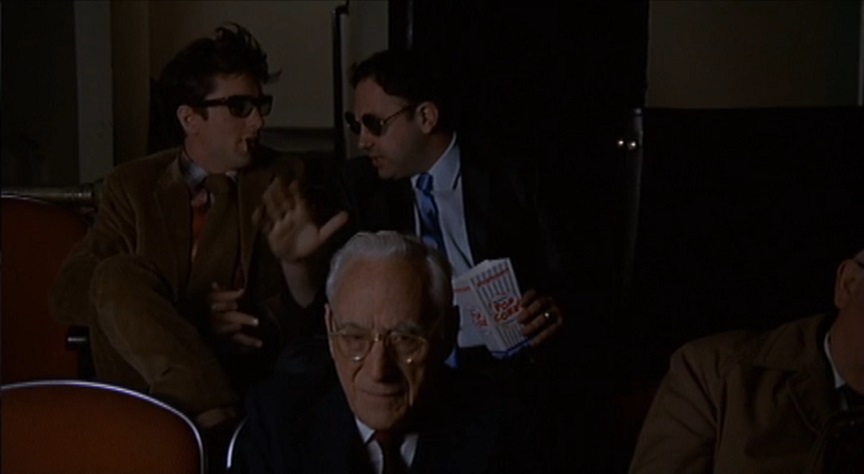

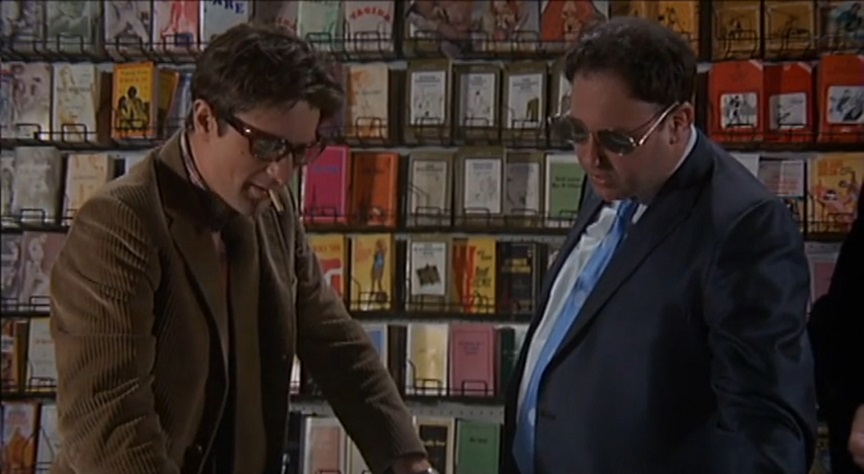

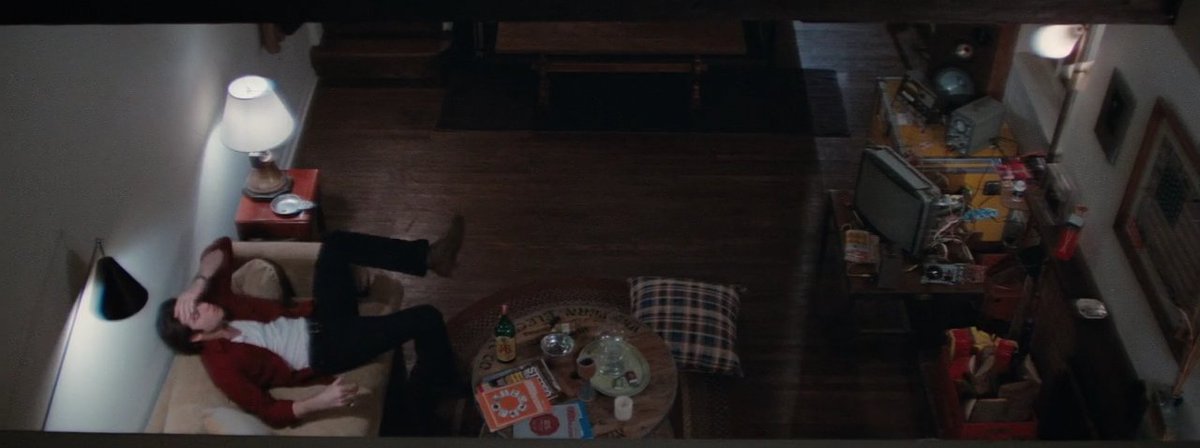

This independent film, which Brian De Palma made in New York in 1970, is an exuberant grab bag of mischievous whimsy that blends radical politics, sexual freedom, racial tension, and emotional hangups with the director’s own catalogue of artistic references, from Hitchcock and the French New Wave to cinéma vérité and avant-garde theatre—and adds a freewheeling inventiveness and an obstreperous satire all his own. It also showcases the explosive, sardonic young Robert De Niro, as Jon Rubin, a cynic on the make who creates reality-based porn inspired by “Rear Window” and, finding that reality needs his help, seduces one of his subjects (Jennifer Salt) for his camera. De Niro brings unhinged spontaneity to Jon’s Machiavellian calculations, especially in wild and daring scenes involving a militant theatre group that preys violently on its spectators’ liberal guilt. De Palma offers a self-conscious time capsule of downtown sights and moods, especially in his rambunctious, hilarious, yet nonetheless disturbing parodies of public television. In his derisively satirical view, the well-meaning media depicts the day’s furies and outrages in an oblivious objectivity that misses the deeper truths that this movie’s own theatrical exaggerations are meant to capture.

"A good scream is hard to find," Loughrey begins. "Tears can be switched on like a tap. A smile is just a twitch of the muscles. But a scream isn’t produced. It erupts, deep from within the fleshy caverns of someone’s lungs. Blow Out’s notorious shriek, let out by Nancy Allen’s Sally in the film’s final reel, is no ordinary sound. It’s a death cry – a final expression of utter hopelessness, which her lover Jack (John Travolta), a sound designer, then adds to the tacky slasher film he’s working on. 'Now that’s a scream!' his producer exclaims. But the result feels uncanny. A slasher film isn’t reality. It’s an illusion, a ritual. We never connect it to the idea of real human loss."

Loughrey the moves on to explore how Blow Out "questions film’s ability to show us the truth"...

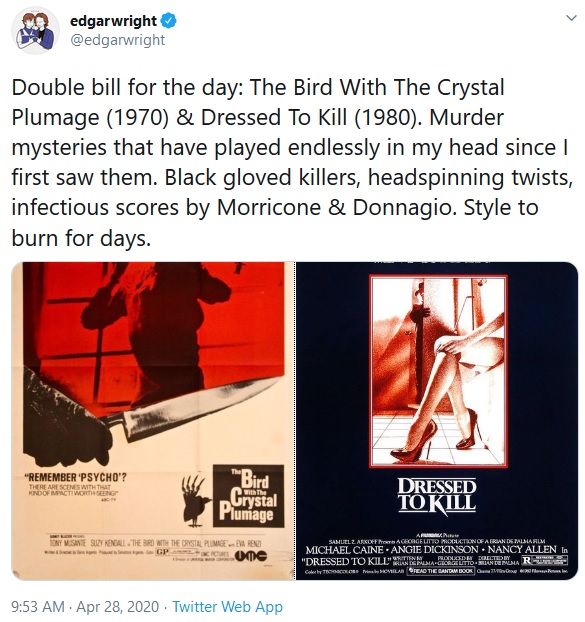

Jack rewinds and replays the tape, trapped in an endless loop. When he gets his hands on a set of photographs of the incident, he attempts to fuse sight and sound together in perfect harmony. But De Palma repeatedly uses his own camera to remind us that Jack will never find the objective truth. He’ll manipulate our view by shooting overhead or using a split-diopter lens – where both the foreground and background are given equal focus. These techniques direct us where to look. They instruct us on how to think and feel. A dizzying 360 shot of Jack’s studio, filled with whirring mechanics, injects a sudden sense of dread. No one has to speak a word for us to sense that something’s gone terribly wrong – his tapes have been erased by an unseen hand.Blow Out was a surprisingly sober, reflective film for De Palma at this juncture in his career. His early films were often politically flavoured – Greetings (1968) features a JFK conspiracy theorist – but he’d grown more provocative over the years. Blow Out’s opening sequence, which jumps into the film Jack’s working on, is a Steadicam shot from the point-of-view of a stereotypical slasher killer. It’s wall-to-wall tits. While it’s primarily a parody of John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978), there’s a nod, also, to De Palma’s own history of lurid eroticism, in the likes of Dressed to Kill (1980) or Sisters (1972).

Despite an estimated budget of $18m, the same as Raiders of the Lost Ark, released that same year, Blow Out flopped at the box office. Quentin Tarantino had a big hand in salvaging the film’s reputation – he listed it as one of his all-time favourites and the reason he cast John Travolta in Pulp Fiction. That’s despite the fact that Vincent Vega is nothing like Jack. Travolta is at his sweetest and most vulnerable here. His baby blue eyes are always clear and attentive.

Audiences had expected more lurid eroticism, what they got was a thriller moored in the paranoia of post-Nixon America, packed with references to the Watergate scandal, the JFK assassination, and Ted Kennedy’s Chappaquiddick incident. Add to that, a drop of (not-so-subtle) irony: the film takes place in Philadelphia during the run-up to the fictional Liberty Day. There are brass bands, fireworks, and American flags several stories tall. It creates a cacophony of sound that nearly drowns out Sally’s piercing, haunting scream – she’s killed to cover up her involvement in the crash. One image of America, a patriotic burlesque, obscures a more truthful one. Jean-Luc Godard may have labelled cinema as “truth at 24 frames per second”, but De Palma himself used Blow Out as the perfect counterargument. As he put it: “The camera lies all the time; lies 24-times-per-second.”

Michael Mann thinks of Al Pacino as like the greater painter Picasso, who creates his art through “a series of brushstrokes”. Take 1995’s Heat, which Mann himself directed, and the actor’s infamous delivery of the line: “She’s got a GREAT ASS!” It’s odd, ludicrous and entirely unexpected – just as Picasso would allow a sudden intrusion of colour or an eye to drop halfway down his subject’s face.Pacino has always been a kind of jack-in-the-box actor. He stores a world-devouring rage deep behind those hungry, coal-black eyes, then turns the crank. Sometimes it explodes out of him; sometimes it’s left to vibrate beneath the surface. He’ll oscillate between the extremes of complete control and complete loss of control – ideas he can apply equally to the roles of criminal, lover, or addict.

A few of Pacino’s characters, such as Tony Montana and Michael Corleone, have become embedded in popular culture. His work is so visible that it’s strangely easy to ignore. He’s won an Oscar, an Emmy, and a Tony (known as the “Triple Crown of Acting”), but also has a history of being snubbed by his peers.

The Academy didn’t reward him for The Godfather, Serpico, or Dog Day Afternoon, but chucked him a conciliatory Oscar in 1993 for his aggressive “hoo-ah”-ing in Scent of a Woman. It’s also led to a tendency to focus on his blips – there’s no talking about Pacino now without bringing up the ironically cringeworthy (and also non-ironically cringeworthy) Dunkin’ Donuts rap he did in 2011’s Jack and Jill.

But the trajectory makes sense. So early on in his career did he perfect his craft (with an incredible run between 1971 and 1975) that he’s spent the following decades in desperate search of something new. “A man’s reach should exceed his grasp, or what’s a heaven for?” wrote Robert Browning, in his poem “Andrea del Sarto”. Pacino has quoted it often. The lows have always been worth the highs.

He’s had his own mini-Renaissance of late, thanks to his work in The Irishman, Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood, and Hunters. It’s a formidable string of performances from an actor who turns 80 tomorrow (25 April), though he doesn’t intend to retire anytime soon. There will surely be more great performances to come.

8. Scarface (1983)It’s a stark indictment of Hollywood’s diversity phobia that Pacino, an Italian-American, was cast by Brian De Palma as a Latinx immigrant not once, but twice (more on Carlito’s Way later). But the actor’s take on Tony Montana, a Miami drug dealer who climbs to the top and immediately loses the plot, is the stuff of legend. Cocaine flows through this man’s veins. His delusions have cemented into gilded kitsch. He thinks of a firearm as his “little friend”. Pacino delivers Tony in the same erratic cadence as Frank Slade in Scent of a Woman, but his exorbitance here is justified. Tony isn’t a man; he’s a symbol of total moral corruption. The fact he’s since been adopted as an entrepreneurial cult hero is telling – so is the fact that the decade’s consumerist worship was so absurd that many critics failed to realise that De Palma was operating firmly in the role of satirist.

7. The Irishman (2019)

If the past couple of decades have seen Pacino dip into self-parody, The Irishman was his chance to reassert himself as one of the greats. The same was true of co-stars Robert De Niro and Joe Pesci – even director Martin Scorsese went out and proved he’s still the undisputed master of the gangster genre. It’s a deeply reflective, muted film that works both as a throwback to the golden era of these men’s careers and a critical re-examination of their own legacies. Pacino, playing union president Jimmy Hoffa, reignites his firebrand charisma only to immediately ground it in a complex web of righteousness and moral indignation. It might not be the showiest performance of his career, but it’s a sublime return to form.

6. Carlito’s Way (1993)

Carlito’s Way never deserved its reputation as Scarface’s little sibling. Yes, the surface similarities are there – they’re both De Palma-directed stories that star Pacino as a Latinx criminal type. But they’re tonally alien to each other. Scarface is the parody of masculinity, while Carlito’s Way tackles the idea with far more sincerity. Its main character, Carlito Brigante, has vowed to go straight, but finds that the past is near-impossible to escape. And so Pacino’s approach here is to go softer and more understated, underpinned by a sense of tragic inevitability. When harassed by Benny (John Leguizamo), a cocksure younger gangster, you can feel Carlito’s old impulse for violence rear its head. But he tries to push it down. He fumbles a little. His eyes flit around the room, suddenly filled with uncertainty. Carlito’s clearly uncomfortable with this new skin he’s crafted for himself. When his newfound dedication to morality backfires, audiences are sure to come away with a bitter taste in their mouth.

1. The Godfather Part II (1974)Michael Corleone is, undeniably, the greatest role of the actor’s career. What makes the difference between his performance in the first and second Godfather films (the third is probably best left unmentioned) is the extent of his transformation. He starts to fall in Part I, but becomes unrecognisable by Part II. He’s a man now willing to murder his own family in order to keep its sanctity. When he gives his brother Fredo (John Cazale) the kiss of death, his emotions shift so quickly between raptorial fury – there’s a moment you think he might just crush Fredo with his own hands – and a profound sense of loss. It’s heartbreaking to see anyone so utterly consumed by darkness. Coppola inserts flashbacks to the crimes of Michael’s father, Vito Corleone (Robert De Niro), to hammer home the cyclical nature of violence. It’s one of Hollywood’s great tragic arcs. And Pacino commits like his life depends on it – those eyes we’re so used to seeing filled with fiery rage are now also flecked with deep guilt and regret. Pacino was nominated for an Oscar for The Godfather Part II, but lost the award to Art Carney for Harry and Tonto. It remains one of the Academy’s most outrageous blunders.