ILLUSTRATION BY XAVIER ONRUBIA, FLATMATE STUDIO

Updated: Tuesday, June 30, 2020 1:55 AM CDT

Post Comment | Permalink | Share This Post

Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | June 2020 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 |

| 28 | 29 | 30 | ||||

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

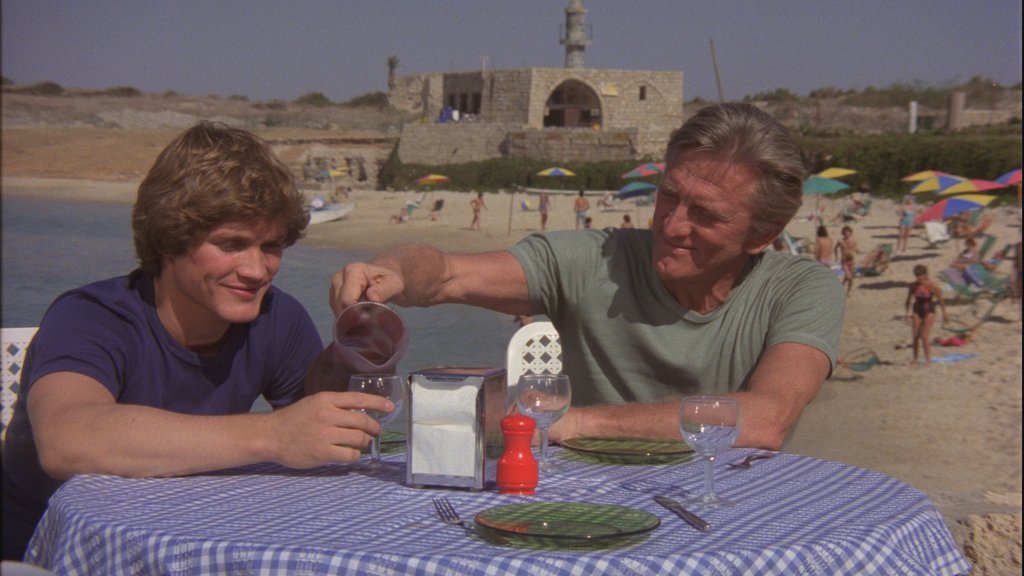

As soon as I got back to the states, I had auditioned years before for these guys I'd never heard of named George Lucas and Brian De Palma. And they were casting together two little movies... this weird Star Wars movie that I thought made no sense, and a movie called Carrie, which was actually appropriate for me and my age at the time. But De Palma elected to go with William Katt and Sissy Spacek, who were a half a generation older than me. But he had remembered me, and I got an audition for this movie called The Fury. And he actually booked me for the role. The problem was, I was under contract to Universal Studios, and I had to get permission to be loaned out from Universal to 20th Century Fox. And the studio just paid me my rudimentary, probably $500 a week, and negotiated a big salary for me on The Fury, and took all the money. But what complicated matters was that I was shooting an NBC Universal series at the time called The Oregon Trail, and we were in Flagstaff, Arizona. So the studios worked together, Universal and Fox, to work out a schedule, and I bounced back and forth continually from Flagstaff, Arizona to Los Angeles, Chicago, and ultimately Israel, where we shot The Fury.Kirk Douglas couldn't have been nicer. He was warm, he was embracing, he was paternal, he had no attitude whatsoever. And when I really saw the grandeur of his iconic celebrity was when we got to Israel, and he was the biggest star in the world in Israel. [Andrews mimics an Israeli accent] "Kirk Douglas! Kirk Douglas!" Because Kirk Douglas was Jewish, and he was revered and loved by all Israelis. And he was like... imagine traveling with The Beatles, and still, he was... he was gregarious, he was not reclusive, he was inclusive. And when we shot a whole sequence in Caesarea-- we originally based in Tel Aviv, and then went to Caesarea where we shot the terrorist sequence where I think my dad's been killed, and John Cassavetes whisks me away-- and Kirk and I had sort of a swimming competition [starts laughing] I remember that when we got in the ocean and we were racing in to shore, actually, I was beating Kirk Douglas, and De Palma said, "Slow down, slow down." He said, "You can't win, and at the most, you have to tie."

So, but it was a great scene, sitting around this table there. De Palma set a dolly track that was 180 degree semi-circle, and we shot the scene in one take. We did several takes of this particular one-take, but there were no cuts in that scene where we're eating and talking, and then Cassavetes comes over, I think I go to the men's room or whatever, and then all hell breaks loose.

Then, today, I came across a quote from an interview with De Palma in the New York Times, published upon the release of Passion. For the article, Nicolas Rapold had wanted to sit with De Palma while the two viewed clips from older films that inspired parts of Passion, but De Palma playfully suggested they watch clips from his own films instead, saying, "I could only refer to my own films. Nobody does this but me."

As they watch the split screen sequence from De Palma's Sisters, De Palma tells Rapold, "The thing about split screen is: It’s a kind of meditative form. You can go very slowly with it, because there’s a lot to look at. People are making juxtapositions in their mind. And you can have all this exposition mumbo jumbo on one side."

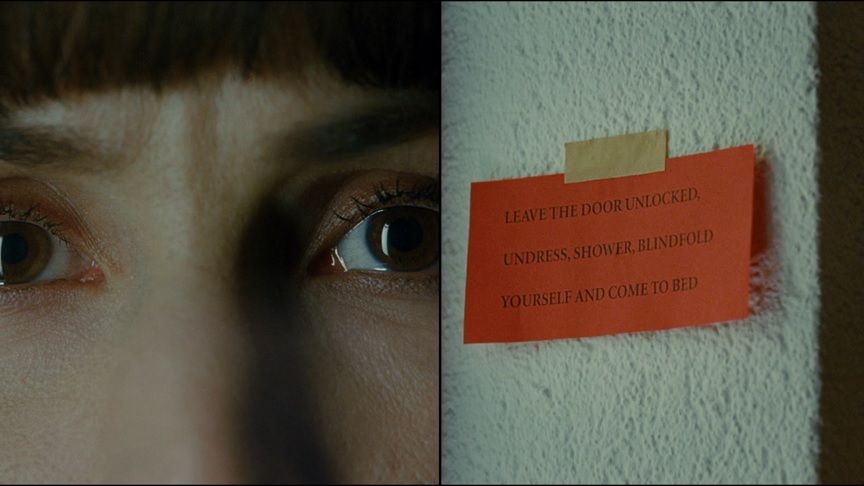

The part of the quote that stuck with me was that split screen is "kind of a meditative form." It strikes me that De Palma's use of split screen has gotten more and more meditative in his later films: from the juxtapositions of fictions and truth in the complex split screen machinations of Snake Eyes, to the where-are-we-now and who's-watching-who blender of surveillance, thievery, and art in the split screen sequence from Femme Fatale. And then there is the split screen in Passion, which is so oddly beautiful and eerie at the same time. Rapold and De Palma watch that sequence for the article, as well:

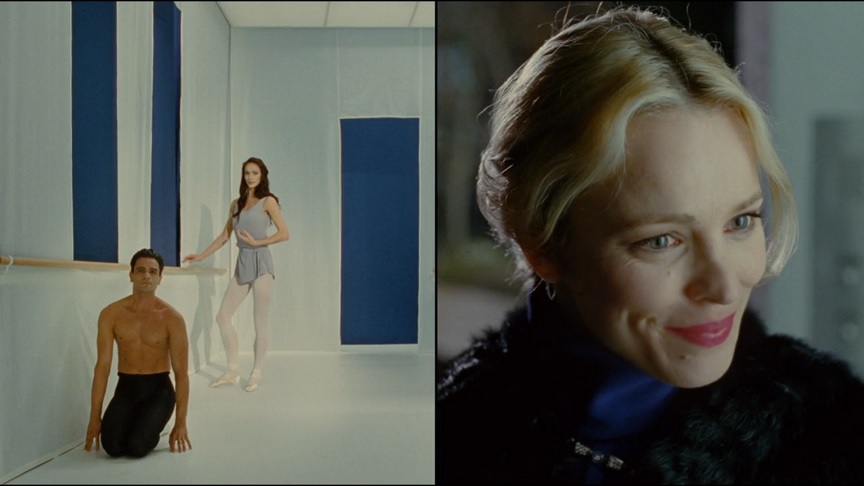

Some filmmakers claim not to watch their own films, or say they only see the mistakes. Mr. De Palma displayed no such qualms as he pored over the split-screen sequence in “Passion.”On the right-hand side, Ms. McAdams as Christine goes about her business after a party at home, showering undisturbed.

“I told her, ‘Just get yourself ready,’ and she could make that as long or as short as she wanted,” Mr. De Palma said. “I would just cut it.”

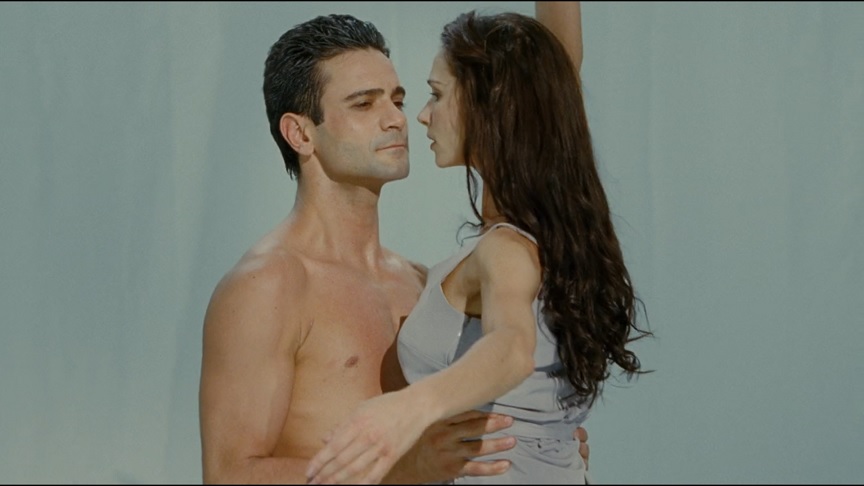

On the left, as the ballet unfolds, the image cuts from a tight close-up on Ms. Rapace’s eyes to the duet in progress. The piece is Jerome Robbins’s version of “Afternoon of a Faun,” in which a couple dance as if facing the mirrored wall of a studio. In Mr. De Palma’s hands, that means they’re looking dead into the camera.

Meanwhile, somebody’s now in Christine’s house.

“You’re lulling the audience,” Mr. De Palma said of the combination of sequences. “I had no idea how it would work. I just had an instinct about it. This is your very typical point-of-view murderer shot, but here juxtaposed against this beautiful ballet.”

The dance grows more intimate. Christine’s stalker comes closer. Art on the left, death on the right.

“And then whack!” he exclaimed.

It was a resounding end to the scene, but just another step in Mr. De Palma’s nightmarish world of suspense.

"There’s an alternate reality out there in which we’re all at the multiplex, or at least able to go, and watching all of the big blockbusters that were originally scheduled to come out in the summer of 2020," Wonder Woman 1984, we can still go back to 1984 and watch all the movies that would have been playing in theaters while Wonder Woman was fighting supervillains."

Bibbiani's alphabetical list also includes Joe Dante's Gremlins, Neil Jordan's The Company of Wolves, Tim Burton's short film, Frankenweenie, Wes Craven's A Nightmare On Elm Street, and several others. Here's what Bibbiani says about Body Double:

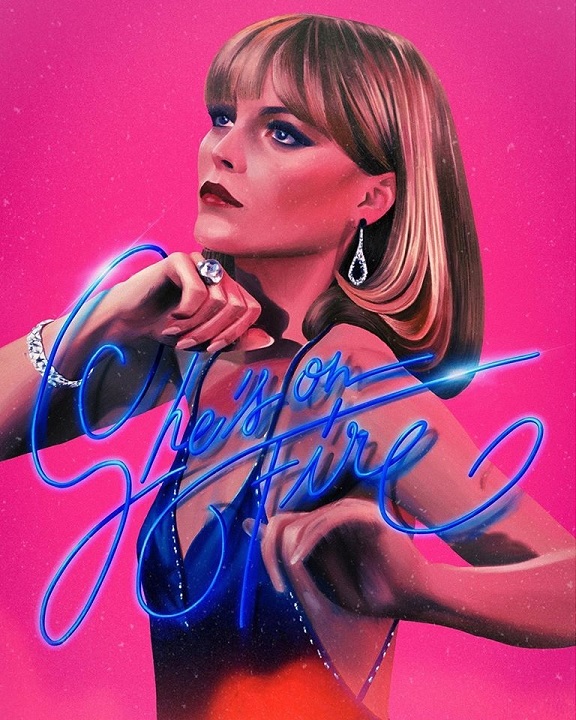

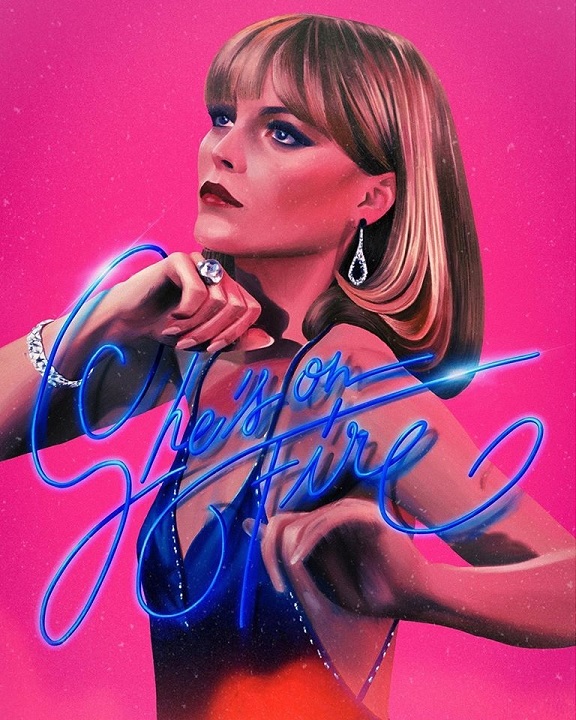

Brian De Palma’s lurid pastiche of Hitchcock’s Rear Window, Vertigo and Dial M for Murder stars Craig Wasson (A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors) as a sad-sack struggling actor who takes a housesitting gig and falls in love with a beautiful neighbor through a telescope, watching her as she seductively dances at night. His late night voyeurism makes him the only witness to her brutal murder, but the plot takes a bizarre turn when he notices that a famous porn star named Holly Body, played by a never-better Melanie Griffith, has the exact same sensual dance routine in her films.The creepy psychosexual subtext of Hitchcock’s films is laid bare, front and center, in De Palma’s Body Double, a film which showcases some of the most ambitious and playful camerawork of the director’s career. Even when it’s not shockingly violent Body Double still feels shocking, as Wasson’s hapless protagonist discovers the depths of his own obsessions and the bizarre lengths he will go to in order to seduce the woman (women?) of his dreams. Meanwhile, Melanie Griffith challenges all expectations in her performance, revealing Holly Body to be as complete, as radical, and as intriguing a character as any in De Palma’s filmography.

First of all a disclaimer: despite being a teenager for much of the 1980s, I didn’t see my favourite film of the 1980s in the 1980s. Instead, I needed Quentin Tarantino to tip me the wink in the wake of the release of Reservoir Dogs in 1992, when he deliriously sang the praises of the film’s director and his gangster epic. “When Brian De Palma would come out with a new movie, the whole first two weeks before the movie opened, I would count down the days,” said QT. “That week before Scarface opened, that was Scarface Week.”My own Scarface week came soon after, when I eventually tracked down a secondhand VHS tape of the movie and I could finally say hello to my little Cuban friend. And I must have watched it nearly half a dozen times (I took Sunday off). Al Pacino’s hammy performance as Tony Montana – “You fuck with me, you fuckin’ with the best” – is a glorious over-the-top riot of violence, Hawaiian shirts, Giorgio Moroder synth sounds and piles and piles and piles of cocaine. Oliver Stone, who wrote the script that included 207 uses of the word “fuck”, admitted he had been a coke addict for two years before sitting down to write the story (“Scarface was me taking my revenge on that drug,” Stone said) of a Marielito who arrives in Miami from the gutters of Havana with the intention of going “right to the top”.

In its depiction of 1980s pop culture, inelegantly wasted lives and hardcore excess, it is untouchable (if De Palma fans can pardon the pun). Plus, it had one of the best movie posters ever. If I could order you to watch this film, I would… but as Tony Montana would say: “The only thing in this world that gives orders is balls.” Preach.

Well, it must be the winter of my discontent

I wish you'd've taken me with you wherever you went

They talk all night and they talk all day

Not for a minute do I believe anything they say

I'm gon' bring someone to life, someone I've never seen

You know what I mean, you know exactly what I meanI'll take the Scarface Pacino and The Godfather Brando

Mix it up in a tank and get a robot commando

If I do it upright and put the head on straight

I'll be saved by the creature that I createI'll get blood from a cactus, gunpowder from ice

I don't gamble with cards and I don't shoot no dice

If you look at my face with your sightless eyes

Can you cross your heart and hope to die?

I'll bring someone to life, someone for real

Someone who feels the way that I feel

Drew Taylor: Brian De Palma recently talked about how Mission: Impossible and Carlito's Way were the highlights of his career. And I want to know what you're experience was on these movies, and sort of what your take was.Koepp: They were great. Brian and I have stayed close friends ever since. He lives just a couple miles away. We have socially-distanced coffee from time to time.

They were turbulent. Of the three movies I did with Brian, the only peaceful one was Snake Eyes. But I think the other two are stronger films, in part because of the chaos and fighting and friction. You know, the old expression, "Bad experience, good film. Good experience, bad film." So, I mean, I loved them. They were really fun, and even though there was fighting, I always felt Brian and I were allies. Even when he fired me-- had to fire me and rehire me-- on Mission: Impossible. He just the other day said, "You know, I think I was the first person to ever fire you." Yeah, Brian, you know [laughs], so what?!? You came back, didn't ya? But they were great experiences, yeah.

Drew: In the documentary, he talks about how you and Robert Towne were in different hotel rooms in the same hotel, working on different drafts of Mission: Impossible. [Laughing] Did you know there was a guy next door working on the same...

Koepp: Yeah, they didn't put us in the same hotel, actually. He was in the Dorchester, I was in the old Hyde Park Hotel, which is now the Mandarin. But yeah, it was really stressy. Once the movie got up and running, or once Paramount greenlit it, Tom got rather anxious, and wanted to bring Towne in to work on it. And then Towne came in, and Brian didn't want-- [Koepp throws his hands in the air] yeah, there was a lot of fighting. And then Towne came in and threw all the pages up in the air. And things stayed quite chaotic. And then three weeks before shooting, they said, "Will you come back... you know, try and put it all back together. But Bob's going to keep working, and you're going to keep working, and we'll just figure out what we shoot." I was like, "Okay... this oughta be interesting."

Drew: Has there ever been a situation where the movie was just too chaotic, or the script was in such disrepair, that you said, "I can't do this"?

Koepp: You know, I've always been able to find an appropriate moment to leave, if I needed to leave. I never had a dramatic leaving. I think, sometimes... and I think I've gotten better at it as I've gotten older. John Kamps and I wrote Zathura, that Jon Favreau directed, and Favreau really wanted to take a pass at it himself. We didn't want him to, so it seemed to make sense to leave, and, you know, let him do that. Which I think he was about to implement anyway, so, you know, [laughing] I'm not sure if I had walked out or was shoved. It's fine, I guess. You know, you gotta sometimes take your own shot at stuff. I didn't want to let that go, because it had a lot of my two sons in it. So it was a lot of personal stuff. I didn't want to leave it to somebody else. So, I think I probably threw a hissy fit on the phone as I left.

Other than that, you kind of know when you're time is up on a movie. Because usually if you get fired, or quit, it's not because people are unpleasant. It's because you're out of ideas. Or your ideas are just not jelling with theirs.

When I saw Brian De Palma’s Mission to Mars in 2000 with a heckling, pre-release audience, I didn’t think much of it. A year later, though, the American Museum of the Moving Image in Astoria screened it on a double bill with The Fury as part of a month-long De Palma retrospective, and a group of former students who took me out there to see The Fury persuaded me to stay and take a second look at Mission to Mars. Perhaps it was the juxtaposition of the two movies that made me look at Mission to Mars with new eyes, but the second time around I fell in love with it. The Fury has an almost insane narrative, but it’s a work of such visual inventiveness and emotional potency that, if you connect with it, the story is no obstacle; its excesses serve the movie just as equally ridiculous stories serve Jacobean tragedies and nineteenth-century operas. And though Mission to Mars has a much simpler silly plot, it too is a kind of outline – you might say a metaphor – for De Palma’s ideas about the tension between technology and humanity and the nature of loss, his two favorite subjects.The movie is actually about two missions to Mars, occurring a quarter-century into the millennium and a year apart. The first, involving a bicultural crew (Americans and Russians), falls to pieces when, having established themselves on the apparently unpopulated planet, they come across a structure in the crimson sand that responds to their attempts to penetrate it with an explosion that buries three of the four astronauts, sparing only Luke Graham (Don Cheadle). Earth loses contact with Luke; his comrades back home don’t know what’s happened to him or his crewmates. So they send another group up, a rescue mission, made up of Phil Ohlmyer (Jerry O’Connell), a young computer hot dog, and Luke’s three best friends, whom he trained with – a married couple, Woody Blake (Tim Robbins) and Terri Fisher (Connie Nielsen), and Jim McConnell (Gary Sinise), who would have manned the first trip with his wife if she hadn’t suddenly taken ill and wasted away from cancer. Derailed by the tragedy, Jim lost his place in the hierarchy. Now Woody and Terri persuade their boss (Armin Mueller-Stahl) to reinstate him, and he winds up in space along with them. But their vehicle crashes and Woody is an indirect casualty of the crash. The others land on Mars, where they find Luke, living alone in his space station and so haunted by ghosts that at first he assumes Jim is one, too. And they find the structure that swallowed up his crewmates. Seen from the air, it’s an exquisite sculpture of a smiling face.

The key to gaining access to the face in the sand, it turns out, is the crew’s ability to furnish proof that they’re human. Mission to Mars is a space story, but it’s the anti-2001: A Space Odyssey. In De Palma’s Blow Out, the hero (John Travolta) keeps making the mistake of putting his faith in technology; so, on a smaller scale, does the teenage boy (Keith Gordon) in Dressed to Kill who’s trying to track down his mother’s killer. For these characters, technology is at best inadequate to achieve the (human, emotional) ends they want to put it at the service of; at worst it backfires and results in the deaths of the people they care about. By the time Mission to Mars takes place, technology is inescapably the ruling force, but De Palma uses the fact of all this technology, ironically, as a way of focusing on the human dilemmas that beset the people who have to deal with its inadequacy and its capacity for bringing disaster. Science has found a way for the astronauts to float through space without the benefit of a space capsule, but only for limited amounts of time, i.e., only as long as the oxygen in the tanks strapped to their backs holds out. When Woody is unable to harness the drifting capsule after the rest of the spaceship has crashed, he finds he hasn’t enough oxygen left to return to his companions. Terri insists she should float out to rescue him – a futile act that would end up killing both of them. So Woody pulls off his helmet and meets the lethal pressure of Mars’s atmosphere head-on, an act of self-sacrifice that comes out of his love for his wife. The separation of husband and wife plays off one of the movie’s most ecstatic visual moments, when they dance together to a Motown tune in the gravity-free atmosphere of the spaceship en route to Mars. But De Palma fans will also recognize his trademark image – the character who watches in helpless anguish while someone, usually a loved one, is destroyed before his or her eyes – from The Fury, Dressed to Kill, Blow Out, Casualties of War and Mission: Impossible. Woody’s demise may be the most strangely poetic version yet of a motif that amounts to an obsession: Robbins’s face turns, magnificently, to cracked granite.

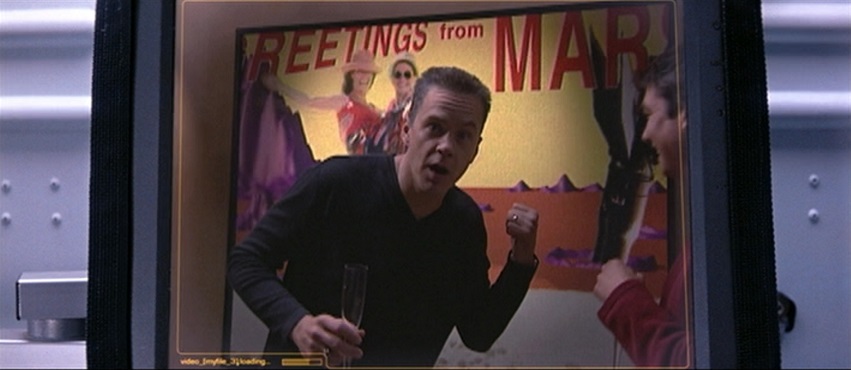

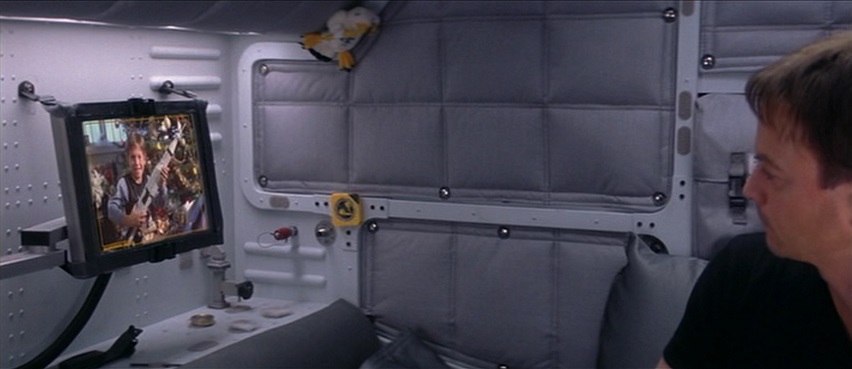

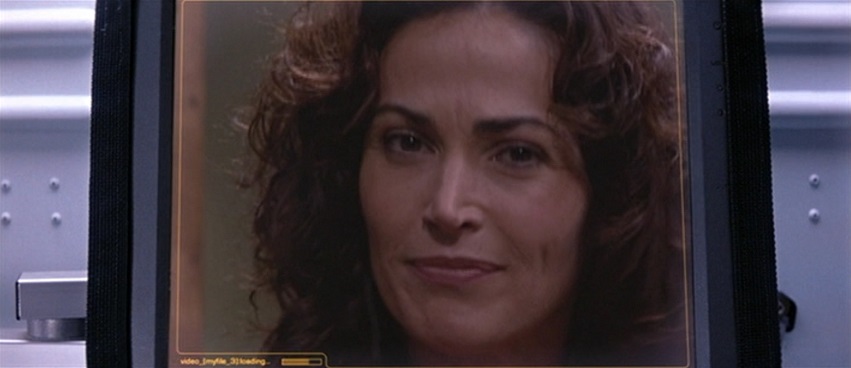

The tragedy that divides Woody and Terri echoes, of course, the loss of Jim’s wife Maggie, whom we see only once, in a video (played, touchingly, by Kim Delaney) their friends prepared when they were chosen to helm the Mars mission. Jim watches it on a monitor in the ship when he winds up traveling there without her. It’s a double-time frame sequence – the video contains images from this joyous time interspersed with earlier ones from the McConnells’ wedding. I might not have made this connection had I not just rewatched The Fury, but the visual dynamic of an image embedded within another image and two sets of observers recalls the scenes in that movie where Amy Irving is caught in a psychic link with a besieged Andrew Stevens while someone else – who can’t see what she sees – tries to communicate with her. This is a visual notion with amazing emotional resonance for these stories of loss. In The Fury, Irving’s Gillian longs to meet the boy who shares her freakish psychic gifts; her separation from him, except in these imperiled visions she has no power to alter, underscores her isolation from the rest of the world, from the people she loves who don’t share her abilities. And when she finally does get close to him, it’s too late: he’s already destroyed. The video that brings Jim’s wife back to him, if only for a few minutes, is a trick of technology that is finally just a reminder of the uncrossable distance between them. He can replay this moment of happiness and relive not only his loss but also his bafflement: here they are at the peak of their lives together, anticipating a future that, though neither knows it, will never come to pass. In the video Maggie makes a toast to them standing at the threshold of a new world, but mere months later she was sick and he stood on the threshold of life and death, watching the most important person in his life fading away from him. De Palma gets at this idea in another way, too. The transmissions the first Mars crew sends back to earth have a twenty-minute delay. Back at home, Jim and the others watch as Luke and his companions, full of good humor and optimism, light a candle in a slab of cake to honor Jim’s birthday before setting out across the sand to explore the structure. The NASA observers have no way of knowing that even while they’re watching this transmission, twenty minutes after Luke sends it, his crew is being torn apart.

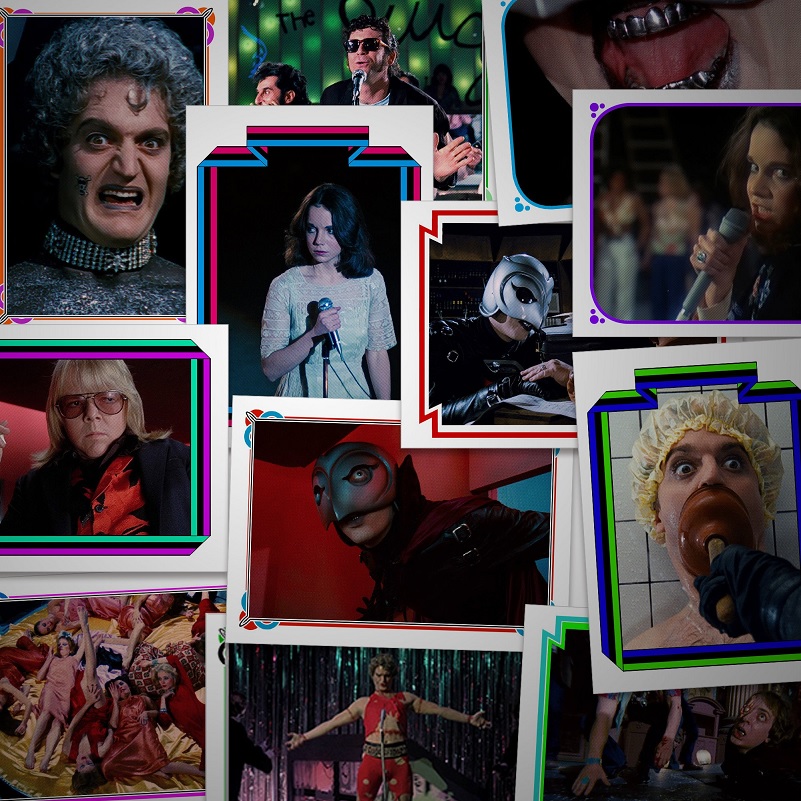

To that end, McBride also has several Phantom Of The Paradise prints available on the site, including one for the fictional "Beef Meets The Phantom Of The Park." Definitely worth checking out.