IN THE END CREDITS OF 'ISLE OF DOGS'

Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | February 2018 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

| 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 |

| 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | |||

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

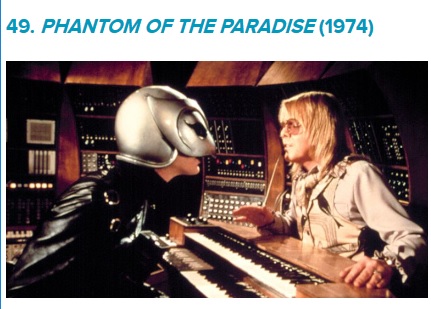

Last week, Consequence Of Sound posted its list of "The 50 Greatest Rock and Roll Movies of All Time." Phantom Of The Paradise made the list at number 49 (Edgar Wright's Baby Driver is number 50). "Phantom of the Paradise is Brian De Palma’s most whimsical and traditionally funny film," states CoS' Mike Vanderbilt in the film's entry blurb. "Good rock and roll has a sense of humor amid the cynicism and melodrama of the music. Phantom sardonically skewers the music industry, turning a record contract into a Faustian deal with the devil. Paul Williams brilliantly plays against type as the evil Swan and provides a wonderfully bizarre collection of tunes for the soundtrack, featuring faux ‘50s nostalgia with “Goodbye, Eddie, Goodbye”, the Linda Ronstadt-style country-tinged pop of “Special to Me”, the glammy “Life at Last”, and the gloriously cynical closer, “The Hell of It”.

Last week, Consequence Of Sound posted its list of "The 50 Greatest Rock and Roll Movies of All Time." Phantom Of The Paradise made the list at number 49 (Edgar Wright's Baby Driver is number 50). "Phantom of the Paradise is Brian De Palma’s most whimsical and traditionally funny film," states CoS' Mike Vanderbilt in the film's entry blurb. "Good rock and roll has a sense of humor amid the cynicism and melodrama of the music. Phantom sardonically skewers the music industry, turning a record contract into a Faustian deal with the devil. Paul Williams brilliantly plays against type as the evil Swan and provides a wonderfully bizarre collection of tunes for the soundtrack, featuring faux ‘50s nostalgia with “Goodbye, Eddie, Goodbye”, the Linda Ronstadt-style country-tinged pop of “Special to Me”, the glammy “Life at Last”, and the gloriously cynical closer, “The Hell of It”.

If anyone can turn the Stormy Daniels scandal into something unforgettable on the big screen, it’s got to be Brian De Palma. The director perfected the art of the erotic thriller in films such as “Body Double” and “Dressed to Kill,” and his touch of heightened sensuality would really make the story about the shady dealings between an arrogant businessman and a porn star pop. Just imagine the meeting between Daniels and Trump with De Palma’s crooked angles, sharp editing, salacious dialogue, and suggestive lighting. He’d give the story the wicked sensationalism it deserves while going for the jugular by criticizing every viewer’s fascination with it in the first place. Trump wouldn’t stand a chance against De Palma.

Director George Romero consciously evoked racism’s rapacity and America’s horrific history of racially motivated lynching. Although Romero’s premise (co-written with John A. Russo) inspired the zombie genre that has become newly popular this millennium (it is a contemporary symptom of our subconscious social anxiety), his film, for all that, was not ahead of its time. In other words, it did not anticipate the insipid movie Get Out, which has become a favorite totem of self-congratulatory liberals intent on defending themselves against the stigma of racism. In that useless process, they make a mess of the millennium’s racial consciousness. Romero’s conceit has been misappropriated and transformed into the paranoia of victimhood, which reverses the lessons that Night of the Living Dead taught and trivializes what makes the film still fascinating, still unnerving.Working outside the Hollywood film industry as a Pittsburgh-based veteran of industrial films, commercials, and political spots (such as for Republican John Tabor’s 1969 Pittsburgh mayoral campaign), Romero perceived the discontents that Hollywood largely ignored in ’68.

Consider that the film first appeared alongside the socially conscious Uptight (Jules Dassin’s ghetto remake of John Ford’s IRA classic The Informer) and Sidney Poitier’s pioneering romantic comedy For Love of Ivy — movies that showed Hollywood’s conscious response to America’s restless black presence. Nineteen sixty-eight was also the year of echt R&B (the alternately hopeful, despairing, and defiant “You’re All I Need to Get By On,” “I Wish It Would Rain,” “Say It Loud, I’m Black and I’m Proud”) and, ultimately, of Martin Luther King’s assassination. Although these connections in hindsight do not weigh upon Romero’s movie, the fact is that Night of the Living Dead edged beyond mainstream Hollywood liberalism; it was part of the same cultural ferment as those films and songs. It stands on its own as a surprisingly stark, unpretentious depiction of panic and compassion.

The scenes of Romero’s mobilized vigilantes hunting down zombies uncannily resemble the black-and-white TV-news footage of marauding southern whites in the civil-rights era. Romero flips our cultural perception to force a simple but disturbing point about America, then on the verge of collapse. Ben’s life is caught within the slight, slippery distance between homegrown terror and homegrown self-defense. At one point, Romero’s narrative, which already included snippets of TV and radio broadcasts, folds in on itself and becomes surreal. It climaxes with a shocking series of stills of Ben’s dead black body, being grappled by white men carrying stevedore hooks, then thrown upon a pile of corpses — a one-man holocaust montage.

This cautionary filmmaking stings, largely because it shares in the media’s modern spectacle of annihilation but lacks today’s maudlin platitudes and arrogant gloating. (Fifty years ago, cinema was at its artistic peak, producing great works of social and psychic consciousness, such as Gillo Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers and Godard’s Masculin Féminin, which featured a brief reenactment of LeRoi Jones’s play Dutchman, an intelligent, provocative precursor of both Night of the Living Dead and Get Out.)

Romero’s crudely effective technique gave his topical issues the inexorable compulsion of a nightmare like Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974), another evocation of frightening, unpredictable Americana. These movies are as terrifying as they are unpretentious. I never bought the idea that they are cathartic; their shock and psychological resonance result from the demonstration that when such racial fears are raised, there’s nothing to laugh about.

*****

Not only is Get Out a poor example of the horror genre. Its generic mishap — combining fear and comedy to supposedly meaningful purpose — fumbles Romero’s (and LeRoi Jones’s) insight. Writer-director Jordan Peele reveals a lack of seriousness about both his subject and the history of politicized filmmaking. In 1970, Brian De Palma advanced from Romero and made his first great film, Hi, Mom! — a satire on activism and the media. Its climax parodied both avant-garde theater and Public Television reality, in an extended skit titled “Be Black, Baby!” that combined black racial anger, white racial fear, and the cultural establishment’s pretenses. In 1973, De Palma went further, with the horror film Sisters, another mixed-genre tour de force spotlighting an interracial liaison (Lisle Wilson and Margot Kidder) on a TV game show titled “Peeping Toms,” combining transgressive voyeurism and miscegenation.

Get Out fans probably don’t know these precedents. As victims of our disconnected culture’s amnesia and miseducation, they ignore Romero and De Palma’s once-countercultural experiments and investigations into racial anxiety, but then they fall for the mainstream media’s manipulation of social fears.

The Backstage casting call does not specify a gender for the lead role of Winslow Leach/The Phantom: "tenor; a struggling young nerdy musician/songwriter who is both the anti-hero and the main protagonist. Winslow makes a futile attempt to advertise their talents by playing at a club owned by Swan, a nefarious music producer. Swan overhears them playing and orders Winslow’s music stolen so that he can use it to open his groovy new club--'The Paradise.' Swan then promptly frames Winslow for drug dealing, giving them a life sentence in Sing Sing Prison, where they eventually escape, but not before having their teeth removed. Following a rage-fueled escape and a traumatic scarring which disfigures their face, Winslow finally makes their way to the Paradise, taking on the identity of the Phantom to take revenge on Swan."

As can be read in Freeman's post, tickets are $20 in advance, and $25 the day of the show-- I did not find any tickets for sale online as of this morning, but Freeman adds that you can send her a message to reserve tickets "for this almost sold out event." There will also be a preview performance on Sunday, March 11th. Freeman and Sean Pollock are the lead producers.

Here are the other roles listed in the casting call at Backstage -- note the Rocky Horror references:

Phoenix (Lead): Female, 20-45alto; a young singer with strong integrity and hopes of becoming a star, who refuses to partake in the casting couch sessions that Swan has the other young women participate in. Prior to their imprisonment, Winslow met Phoenix at the auditions for Faust and realized she would be perfect for the lead in their cantata--ultimately going so far as to kill anybody who opposed her rise to stardom. Swan, however, despises her perfection and has her demoted to back up singer. She will eventually rise to the occasion, discovering about herself that she's prepared to do anything to earn that crowd applause.

Swan (Lead): Male, 28-50

(Baritenor) Evil CEO and producer of Death Records, Swan is an expert at making hit records and exploiting his musicians for all they're worth--including hosting casting couch sessions to pray on young women. He is arrogant, narcissistic, and always looking for a chance to drum up publicity. Swan has recently finished building his new club “The Paradise” and is looking for the right music to open it with, so he steals Winslow’s.

Beef (Supporting): Male, 25-45

tenor; a self-professed “profess-ion-al,” Beef is brought in to sing Winslow's cantata, after Phoenix was deemed "too perfect." Like most of Swan's acts, Beef is very flamboyant and hooked on drugs. He is narcissistic, superstitious and has the ability to turn either his manliness or femininity up to 11 at will. Very glam rock and Bowie inspired. Ambiguously bisexual--he can flirt with anyone to get whatever he wants. Think a cross between Frank-n-Furter and Rocky from "Rocky Horror."

The Juicy Fruits/The Beach Bums/The Undead (Supporting): 18-35

a trio of three singers, and unofficial chorus of the story. Swan's band, constantly being reformed and renamed to match current trends (they go from Sha Na Na, to The Beach Boys, to KISS). They’re reused as leads and backup singers wherever necessary--partly to save money, but mainly to capitalize on their sheer malleability.

Philbin (Supporting): Male, 25-50

Swan's right-hand man; Philbin's job encompasses a number of fields, including scouting for talent, managing bands, directing the actors and singers on the Paradise set, and enforcing Swan's orders; very butch, stereotypical drug pusher/meathead bodyguard “tough guy” gangster/mob type. Think Eddie from Rocky Horror, but without the groupies or the Rock and Roll fame.

Ensemble (Chorus / Ensemble): 18-45

some roles which will need filling: Secretary, Audition Girls, Bodyguards, Video Camera, and Rock Freak. Some of these will be doubled up.

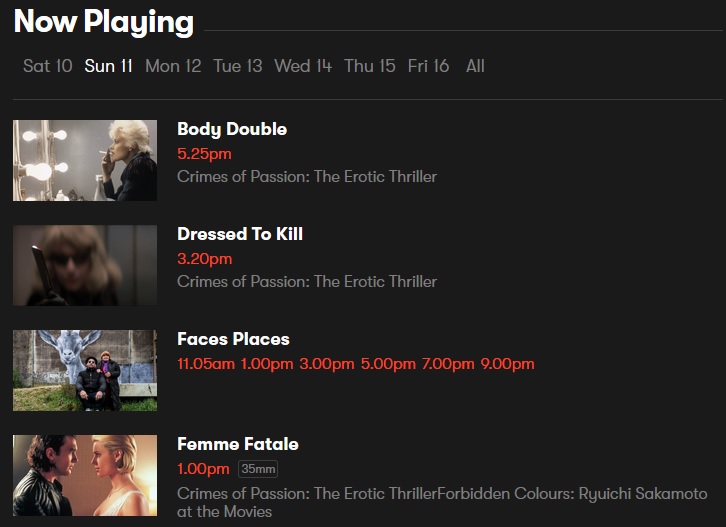

“A complex series of seductions and murders — that’s not something you see a woman do.” This line, spoken early (by a man, of course) in Bob Rafelson’s Black Widow (1987) — which features Theresa Russell as a beautiful psychopath who marries wealthy magnates only to poison them — sets a clean template for erotic thrillers to work against. The often-maligned genre, which flourished in the ’80s and ’90s and functions as an intriguing amalgam of film noir, sexy music video, and pure id, is the subject of “Crimes of Passion: The Erotic Thriller,” a luxuriously sprawling 24-film series running this month at the Quad Cinema. With Valentine’s Day around the corner, the rep house is bringing seduction and murder to the forefront. But it’s worth remembering, amid the enjoyable screen hysterics, that the erotic thriller would be nothing without its femmes fatales. To watch them rebuff the Black Widow line, again and again, is a reliable pleasure.In addition to glossy genre icons like Paul Verhoeven’s Basic Instinct (1992) and Adrian Lyne’s Fatal Attraction (1987), the Quad’s program also offers up some films that haven’t traditionally been described as erotic thrillers. But even more surprisingly, while surveying the canvas of titles on display, is the second connective thread that emerges: “Crimes of Passion” is, in a sense, a short seminar on the femme fatale. The stock character, as old as cinema itself, endures for a reason: Within a society that expects women to be docile, passive figures, the spectacle of a woman behaving badly ignites both lust and a perverse wish fulfillment. It’s a nuanced appeal that reaches beyond the male gaze.

Double Indemnity, Billy Wilder’s 1944 noir classic, is the oldest work in the series; Barbara Stanwyck’s portrayal, in that movie, of a married woman who seduces an insurance salesman into a murderous scheme stands as a template for the genre. Her deviousness would be scandalous in any era. She’s also an obvious inspiration for Kathleen Turner’s character in Body Heat (1981), an early pioneer in heaping horniness onto the handsome noir template and beginning to codify the erotic thriller as a newly steamy genre of its own.

The genre also owes a debt to Alfred Hitchcock. Vertigo (1958), with Kim Novak as a provocative woman who takes on two distinct identities, is one of the great cinematic examples of femininity spiraling into something confusing and sinister. And a particularly ardent Hitchcock follower, Brian De Palma, may well be the auteur of the erotic thriller. With three films, he’s the most-represented director in the series; each of them — Dressed to Kill (1980), Body Double (1984), Femme Fatale (2002) — prominently features crime, plot twists, and babely blondes. It takes some moxie to literally title an erotic thriller “femme fatale,” but De Palma’s the rare director who could actually pull it off. Though he has long had charges of sexism leveled against him, the women in his films project power and know how to use their sexuality to influence those around them. Femme Fatale doesn’t just gawk at its model-turned-actress star, Rebecca Romijn. It builds a head-spinning world of double crosses around her — and, ultimately, gives her the last laugh.

Jordan Peele talks to the Los Angeles Times' Glenn Whipp, in an article inspired by the recent Oscar nominations for Peele's Get Out. Here's a brief excerpt from Whipp's article:

Jordan Peele talks to the Los Angeles Times' Glenn Whipp, in an article inspired by the recent Oscar nominations for Peele's Get Out. Here's a brief excerpt from Whipp's article:Peele has just put me in the same leather armchair that Missy Armitage (Catherine Keener) invites Chris Washington (Oscar nominee Daniel Kaluuya) to sit in before she sends him falling into the Sunken Place. Missy’s floral-accented chair is just off to the left; Peele spreads out on a couch across from me.“I definitely needed to take a couple of things from the set after the movie wrapped,” he says, smiling.

Peele knew the Missy-Chris hypnosis scene would become iconic. But he figured it would take years and, like most horror films, its appreciation would exist on a cult level. Instead “Get Out,” released the weekend “Moonlight” won the best picture Oscar last year, grossed $254 million and became a cultural phenomenon, the subject of endless discussions over its treatment of race and an Oscar powerhouse, earning Peele nominations as a director, writer and producer.

Now Peele, under the Monkeypaw Productions banner, is working hard, indulging his love for horror and the supernatural and boosting representation in genres that historically haven’t been generous toward black people. He’s producing a “Twilight Zone” reboot for CBS All Access and, with Misha Green and J.J. Abrams, an HBO series based on the novel “Lovecraft Country,” a series of interconnected stories that use various classic horror styles to examine the terrors of Jim Crow America.

And he’s writing his next movie.

“I’m in this horror, thriller, parable, ‘Twlight Zone’-y genre, probably forever,” Peele says. “I want to do what Hitchcock did, what Spielberg did, what Brian De Palma did — dark tales.”