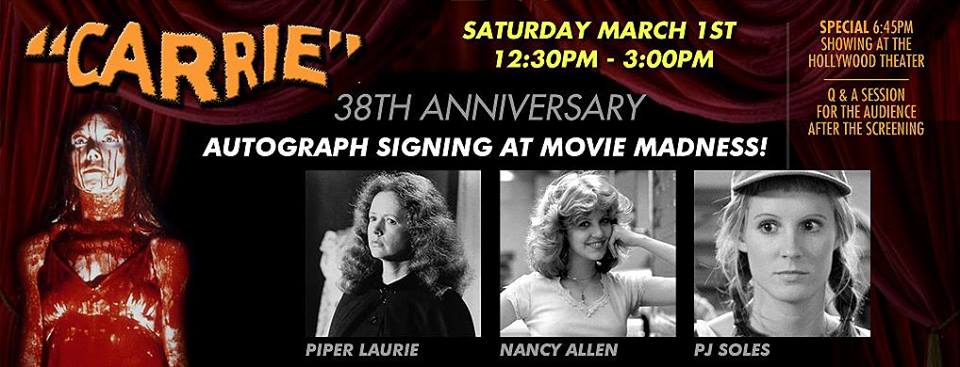

AND THE PRAGUE POST LOOKS AT THE PRAGUE LOCATIONS USED IN DE PALMA'S FILM

Last week, A.V. Club's A.A. Dowd took a look, with spoilers, at the Mission: Impossible film franchise, as part of the site's "Run The Series." Dowd notes that the franchise is, like the Alien franchise, "auteur-driven," as each film is helmed by a different director. "Though they’re all loosely based on the same popular television series," Dowd states, "every one of the four Mission: Impossible movies carves out its own conceptual and stylistic identity. The sequels don’t feel like sequels, but high-concept reboots, as though the gatekeepers of the series were so nervous that their hit formula would go instantly stale that they sought to rewrite it with each subsequent entry. As a result, the nature of Mission: Impossible depends entirely on who’s in the director’s chair.

Last week, A.V. Club's A.A. Dowd took a look, with spoilers, at the Mission: Impossible film franchise, as part of the site's "Run The Series." Dowd notes that the franchise is, like the Alien franchise, "auteur-driven," as each film is helmed by a different director. "Though they’re all loosely based on the same popular television series," Dowd states, "every one of the four Mission: Impossible movies carves out its own conceptual and stylistic identity. The sequels don’t feel like sequels, but high-concept reboots, as though the gatekeepers of the series were so nervous that their hit formula would go instantly stale that they sought to rewrite it with each subsequent entry. As a result, the nature of Mission: Impossible depends entirely on who’s in the director’s chair."Brian De Palma, the New Hollywood veteran who brought M:I to the screen in 1996, offered a paranoid surveillance thriller about distrust of old heroes. Hong Kong heavyweight John Woo, who took the reins next, downplayed espionage in favor of balletic action, fashioning another of his enemies-as-brothers thrillers (this one featuring an enemy so brotherly that he 'doubles' for his rival). Moving from television to movies with his contribution to the series, J.J. Abrams shaped Mission: Impossible III into a big-screen Alias, again examining the attempts of a covert operative to balance professional and personal lives. And Pixar’s Brad Bird, in his fledgling foray into live-action filmmaking, crafted a characteristic ode to exceptional people (à la his The Incredibles), applying a playful animator’s touch to various feats of courage and strength.

"Setting aside thematic thrust, every Mission bears the visual mark of its maker, discernible in any random five-minute stretch of running time. Who but Woo could have made the very turn-of-the-millennium Mission: Impossible II, with its constant slow motion, its double-pistol gunfights, its white doves emerging from a fiery inferno? Who but De Palma could have made the original, flush as it is with split screen, POV shots, and dramatic zooms into faces? Mission: Impossible III proved that Abrams was nuts for lens flares long before Star Trek, while the car-factory finale of Mission: Impossible—Ghost Protocol is a dead ringer for the climaxes of several Pixar movies. Close your eyes and just listen to these films. Their scores—the inappropriate whimsy of Danny Elfman’s, the swelling bombast of Hans Zimmer’s, the third-time’s-a-charm urgency of Michael Giacchino’s—betray a specific time period and sensibility. Whatever one thinks of the individual movies, there’s no mistaking one for another."

The "inappropriate whimsy" of the Danny Elfman score? Hardly-- on the contrary, I find Elfman's score for the first film heavy with dark themes reflecting the betrayals, sadness, and paranoia of the characters, and any of the bombastic whimsy that occasions within some of the action scenes, perhaps, entirely appropriate.

Here is what Dowd has to say about De Palma's film, more specifically:

The biggest hit of his career, Mission: Impossible was the culmination of De Palma’s brief heyday as a Hollywood hit maker. (Just to try to imagine him getting a summer tentpole gig like this today.) But it’s no anonymous sell-out move: From its opening scene, which conflates government surveillance with the voyeurism of cinema, the film is unmistakably the work of the same director who made Blow Out or Dressed To Kill or any of those fabulously stylish, psychosexual ’80s thrillers. By asserting his authorial personality upfront, by conforming this franchise launcher to his own obsessions, De Palma set the precedent for the series. From here on out, the Mission: Impossible films would smuggle personal preoccupations into their crowd-pleasing packages.

After its cold open, Mission: Impossible launches into an homage to the original show’s credit sequence, teasing scenes from the forthcoming adventure with a fast-cut montage of enticing imagery. The callback proves to be a red herring; not long after, the movie throws reverence to the wind by having all but one member of the IMF squad slaughtered—the loud-and-clear message being that, unlike its small-screen predecessor, this Mission: Impossible won’t be a team exercise. Going one step further, De Palma and his writers (the Hollywood dream team of Steven Zaillian, David Koepp, and Robert Towne) later reveal the hero of the TV series, Jim Phelps, to be a double-crossing traitor. The controversial revelation announces that catering to the diehards will not be a goal of this franchise. Today’s geek-friendly adaptations, slavish in their loyalty to The Text, could learn something from the brazen infidelity of Mission: Impossible.

Naturally, fans—and original cast members—greeted these affronts to the show’s legacy with anger. Consensus among the incensed seemed to be that De Palma’s movie had not only butchered the source material, turning it into a vanity project for [Tom] Cruise, but had also applied the Mission: Impossible brand to a soulless Hollywood action flick. That criticism is a bit baffling, frankly. Yes, there are some pyrotechnics, especially during the speeding-train climax, heavily excerpted in the trailers. But in De Palma’s hands, Mission: Impossible is largely an exercise in suspense—in bombs under the table that don’t go off, as his hero Hitchcock might put it. The movie’s most memorable moments, like the undercover op during the party and the famous hanging-from-the-ceiling Langley infiltration, are models of escalating tension. Stealth is privileged over confrontation—a trend that would blessedly continue throughout most of the series.

In fact, the main reason that Woo’s installment now feels like the low point of the franchise is that it abandons the ethos of the original, essentially earning the accusations that were lobbed at De Palma’s movie. Whereas the first film boasts a Hitchockian wrong-man plot, with Hunt framed for a crime he didn’t commit, Mission: Impossible II riffs on Notorious—but only until about the midpoint, at which point Woo hijacks his perverse sleeping-with-the-enemy scenario in favor of some very Woo-ish adrenaline rushes. M:I 2 is a moronically caffeinated extreme-sports highlight reel, its story a thin pretext for rock-chord machismo and shots of its shaggy-haired star striking “badass” poses. (Even more so than the previous film, this one is basically The Cruise Show.) Still, there’s plenty of dumb fun to be had with Woo’s hilariously excessive approach, especially when the director pushes both his own and the series’ trademarks to their self-parodic limits.

'MISSION: IMPOSSIBLE' IN PRAGUE

Here's what the Prague Post's André Crous wrote about the Prague locations used in the first and fourth films:

Brian De Palma’s film adaptation of the well-known television series had some tense moments that were set in the land between West and East, where Americans were still hatching some dastardly plans even as the East’s veil of secrecy was gradually lifting. The first act of this film is set in a Prague where the U.S. Embassy apparently looks exactly like the National History Museum on Wenceslas Square, and main character Ethan Hunt finds himself missing a violent car explosion on Kampa square (Na Kampě), just off Charles Bridge, which is eerily deserted. In the film’s third sequel, the 2011 Mission: Impossible – Ghost Protocol, Prague doubled as Budapest and Moscow (yikes!).

According to

According to

The theme of last night's Oscars telecast was "Heroes", and included time-filler montages of all kinds of movie heroes. One montage, introduced by Sally Field, included a clip of Ness and Malone talking in the church from Brian De Palma's The Untouchables. In another montage, introduced by Chris Evans, a quick-clip from De Palma's Mission: Impossible showed Ethan Hunt landing on top of the train after blasting himself from the helicopter.

The theme of last night's Oscars telecast was "Heroes", and included time-filler montages of all kinds of movie heroes. One montage, introduced by Sally Field, included a clip of Ness and Malone talking in the church from Brian De Palma's The Untouchables. In another montage, introduced by Chris Evans, a quick-clip from De Palma's Mission: Impossible showed Ethan Hunt landing on top of the train after blasting himself from the helicopter.

Brian De Palma's Passion will be included as part of a film series at the

Brian De Palma's Passion will be included as part of a film series at the