Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | March 2014 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | ||||||

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 |

| 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 |

| 30 | 31 | |||||

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

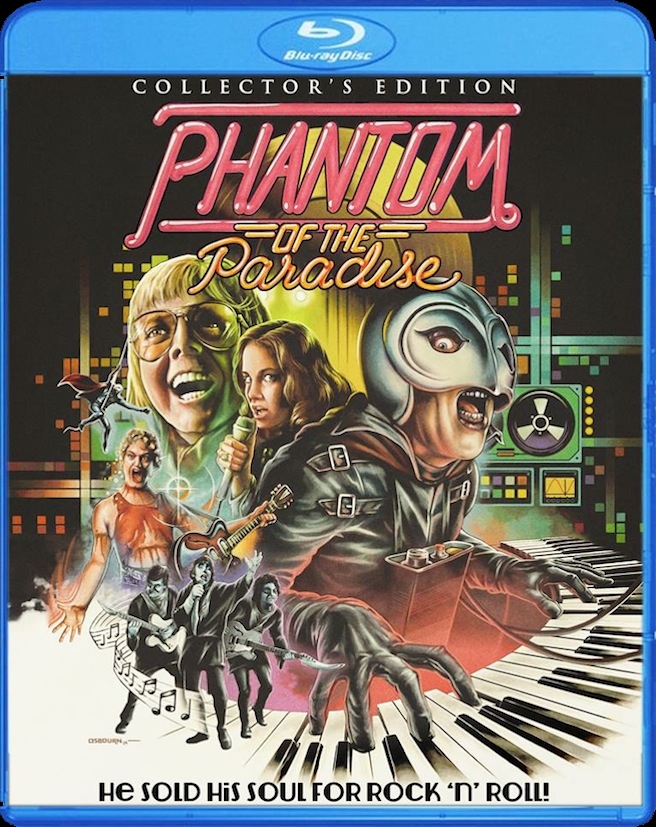

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

Bloody Disgusting has an exclusive video of Maitland McDonagh talking about Brian De Palma's Sisters, which will (maybe?) be part of the extras on Arrow Video's upcoming Blu-Ray/DVD edition of the film. McDonagh wrote an essay about De Palma's Dressed To Kill for Arrow's Blu-Ray edition of that film, released last year. There are a couple of curious discrepancies here, though: for one, while the video shows that Sisters will be released April 14, the Arrow website shows the release date as April 28; the other odd thing is that the Bloody Disgusting headline calls the Maitland McDonagh video an "outtake," although the article by MrDisgusting never uses that word once.

Bloody Disgusting has an exclusive video of Maitland McDonagh talking about Brian De Palma's Sisters, which will (maybe?) be part of the extras on Arrow Video's upcoming Blu-Ray/DVD edition of the film. McDonagh wrote an essay about De Palma's Dressed To Kill for Arrow's Blu-Ray edition of that film, released last year. There are a couple of curious discrepancies here, though: for one, while the video shows that Sisters will be released April 14, the Arrow website shows the release date as April 28; the other odd thing is that the Bloody Disgusting headline calls the Maitland McDonagh video an "outtake," although the article by MrDisgusting never uses that word once.Incidentally, in the video at Bloody Disgusting, McDonagh mentions William Castle's Homicidal, contrasting that film's lack of critical attention to the type of attention De Palma's Sisters received upon its release. De Palma listed Homicidal as one of his "Guilty Pleasures" in an article for Film Comment back in the 1980s.

As we've noted several times over the past few months, Doc Films in Chicago has been hosting a Brian De Palma retrospective, running every Wednesday since January 8. The retrospective ends tomorrow (Wednesday) night with two screenings of Femme Fatale. Programmer Dan Wang writes of the film at the Doc Films website: "Beginning with a rapturous set piece at the Cannes Film Festival, and ending with a statement not only of cinematic aesthetics but also of ethics, Femme Fatale is De Palma's most ambitious, vexing, and confounding work. It is also beautiful, drawing from a more vibrant and painterly palette than earlier films. Starring Rebecca Romijn as a jewel thief and Antonio Banderas as an opportunistic photographer, this film calls to be seen and seen again."

As we've noted several times over the past few months, Doc Films in Chicago has been hosting a Brian De Palma retrospective, running every Wednesday since January 8. The retrospective ends tomorrow (Wednesday) night with two screenings of Femme Fatale. Programmer Dan Wang writes of the film at the Doc Films website: "Beginning with a rapturous set piece at the Cannes Film Festival, and ending with a statement not only of cinematic aesthetics but also of ethics, Femme Fatale is De Palma's most ambitious, vexing, and confounding work. It is also beautiful, drawing from a more vibrant and painterly palette than earlier films. Starring Rebecca Romijn as a jewel thief and Antonio Banderas as an opportunistic photographer, this film calls to be seen and seen again.""Try to imagine a synthesis of every previous Brian De Palma film; you'll come up with something not very different from his first made-in-France movie (2002), a personal project for which he takes sole script credit. I enjoyed every minute of it, maybe because De Palma took such obvious pleasure in putting it all together. If you decide at the outset that this needn't have any recognizable relationship to the world we live in, you might even find it a delight."

Last week, A.V. Club's A.A. Dowd took a look, with spoilers, at the Mission: Impossible film franchise, as part of the site's "Run The Series." Dowd notes that the franchise is, like the Alien franchise, "auteur-driven," as each film is helmed by a different director. "Though they’re all loosely based on the same popular television series," Dowd states, "every one of the four Mission: Impossible movies carves out its own conceptual and stylistic identity. The sequels don’t feel like sequels, but high-concept reboots, as though the gatekeepers of the series were so nervous that their hit formula would go instantly stale that they sought to rewrite it with each subsequent entry. As a result, the nature of Mission: Impossible depends entirely on who’s in the director’s chair.

Last week, A.V. Club's A.A. Dowd took a look, with spoilers, at the Mission: Impossible film franchise, as part of the site's "Run The Series." Dowd notes that the franchise is, like the Alien franchise, "auteur-driven," as each film is helmed by a different director. "Though they’re all loosely based on the same popular television series," Dowd states, "every one of the four Mission: Impossible movies carves out its own conceptual and stylistic identity. The sequels don’t feel like sequels, but high-concept reboots, as though the gatekeepers of the series were so nervous that their hit formula would go instantly stale that they sought to rewrite it with each subsequent entry. As a result, the nature of Mission: Impossible depends entirely on who’s in the director’s chair."Setting aside thematic thrust, every Mission bears the visual mark of its maker, discernible in any random five-minute stretch of running time. Who but Woo could have made the very turn-of-the-millennium Mission: Impossible II, with its constant slow motion, its double-pistol gunfights, its white doves emerging from a fiery inferno? Who but De Palma could have made the original, flush as it is with split screen, POV shots, and dramatic zooms into faces? Mission: Impossible III proved that Abrams was nuts for lens flares long before Star Trek, while the car-factory finale of Mission: Impossible—Ghost Protocol is a dead ringer for the climaxes of several Pixar movies. Close your eyes and just listen to these films. Their scores—the inappropriate whimsy of Danny Elfman’s, the swelling bombast of Hans Zimmer’s, the third-time’s-a-charm urgency of Michael Giacchino’s—betray a specific time period and sensibility. Whatever one thinks of the individual movies, there’s no mistaking one for another."

The "inappropriate whimsy" of the Danny Elfman score? Hardly-- on the contrary, I find Elfman's score for the first film heavy with dark themes reflecting the betrayals, sadness, and paranoia of the characters, and any of the bombastic whimsy that occasions within some of the action scenes, perhaps, entirely appropriate.

Here is what Dowd has to say about De Palma's film, more specifically:

After its cold open, Mission: Impossible launches into an homage to the original show’s credit sequence, teasing scenes from the forthcoming adventure with a fast-cut montage of enticing imagery. The callback proves to be a red herring; not long after, the movie throws reverence to the wind by having all but one member of the IMF squad slaughtered—the loud-and-clear message being that, unlike its small-screen predecessor, this Mission: Impossible won’t be a team exercise. Going one step further, De Palma and his writers (the Hollywood dream team of Steven Zaillian, David Koepp, and Robert Towne) later reveal the hero of the TV series, Jim Phelps, to be a double-crossing traitor. The controversial revelation announces that catering to the diehards will not be a goal of this franchise. Today’s geek-friendly adaptations, slavish in their loyalty to The Text, could learn something from the brazen infidelity of Mission: Impossible.

Naturally, fans—and original cast members—greeted these affronts to the show’s legacy with anger. Consensus among the incensed seemed to be that De Palma’s movie had not only butchered the source material, turning it into a vanity project for [Tom] Cruise, but had also applied the Mission: Impossible brand to a soulless Hollywood action flick. That criticism is a bit baffling, frankly. Yes, there are some pyrotechnics, especially during the speeding-train climax, heavily excerpted in the trailers. But in De Palma’s hands, Mission: Impossible is largely an exercise in suspense—in bombs under the table that don’t go off, as his hero Hitchcock might put it. The movie’s most memorable moments, like the undercover op during the party and the famous hanging-from-the-ceiling Langley infiltration, are models of escalating tension. Stealth is privileged over confrontation—a trend that would blessedly continue throughout most of the series.

In fact, the main reason that Woo’s installment now feels like the low point of the franchise is that it abandons the ethos of the original, essentially earning the accusations that were lobbed at De Palma’s movie. Whereas the first film boasts a Hitchockian wrong-man plot, with Hunt framed for a crime he didn’t commit, Mission: Impossible II riffs on Notorious—but only until about the midpoint, at which point Woo hijacks his perverse sleeping-with-the-enemy scenario in favor of some very Woo-ish adrenaline rushes. M:I 2 is a moronically caffeinated extreme-sports highlight reel, its story a thin pretext for rock-chord machismo and shots of its shaggy-haired star striking “badass” poses. (Even more so than the previous film, this one is basically The Cruise Show.) Still, there’s plenty of dumb fun to be had with Woo’s hilariously excessive approach, especially when the director pushes both his own and the series’ trademarks to their self-parodic limits.

Regarding Grand Piano, Mira tells Brooks, "The irony of this movie is that 20 years ago it would be a mainstream movie. Richard Donner and the late John Frankenheimer are directors that I grew up with and I loved and for some reason, Hollywood has failed to deliver [today].”

After Grand Piano's world premiere at Austin's Fantastic Fest last September, we posted links to several reviews that frequently mentioned filmmakers such as Alfred Hitchcock, Brian De Palma, and Dario Argento. With the theatrical release this weekend, there are more such reviews popping up. Here are some more links:

Drew McWeeny, HitFix

"If you saw Eugenio Mira's earlier film Agnosia, then you may have already noticed his fondness for Brian De Palma. Anyone making thrillers who holds De Palma as part of the pantheon is already on my short list of people I like, but when you see how well Mira pulls it all together for Grand Piano, it's obvious that he's graduated to a different level with this film.

"I think it's very fair to compare this to Non-Stop, which I reviewed earlier today, since both of them are thrillers that take place over a compressed period of time in a fairly restrictive setting with a ticking clock. For both filmmakers, the exercise is the same. Can you keep the film somewhat plausible while ratcheting up the tension and convincing us that things could unfold like this? In the case of Grand Piano, the answer is a resounding yes, and I was delighted by just how playful and fun this is."

Glenn Dunks

"Eugenio Mira’s Grand Piano has a thoroughly ridiculous premise that borrows liberally from films such as Jan de Bont’s Speed, David Fincher’s Panic Room, and, most strikingly, Joel Schumacher’s Phone Booth. Much like that 2002 thriller with Colin Farrell as a man stuck in a telephone booth with a sniper’s rifle fixed on him, Mira’s films features a more-or-less single location with a lone man aware of the stakes and an escalating tension that is seemingly at odds with its intimate focus. Needless to say, it is a better film than Phone Booth, but that may be because the Spanish director (Grand Piano is in fact a Spain/US co-production) decided to reference Brian De Palma more than his most direct influence, Alfred Hitchcock.

"There’s a playfulness to Grand Piano that is deeply rewarding. It’s slick, 35mm lensing is drenched in bold colours, interesting compositions and in some sequences a sense of virtuosic camera trickery. Despite its compact confines, Mira’s film recalls the more heightened sense of Hitchcockian style that ebbs and flows throughout De Palma’s Blow Out, Body Double, or Dressed to Kill rather than the elegance of Hitchcock’s boutique thrills like Rope or The Lady Vanishes. It is a style that is perhaps too obvious for its own good, and yet one that works. It elevates the film and allows its moments of flight and fancy to not strike one as absurd or over-the-top. The entire film is working on a level of OTT sublime that is as much seat-grippingly intense as it is giggle-inducing."

A.A. Dowd, A.V. Club

"Mira, for his part, just gets his Brian De Palma on, most notably during a split-screen sequence that puts the harried hero on one side of the frame and a brutal murder on the other."

Kevin Taft, Edge on the Net

"A nifty little thriller that should cement director Eugenio Mira as 'the' director to watch, Grand Piano is filled with Hitchcockian suspense and gorgeous shades of Brian DePalma. With a compelling performance by Elijah Wood... the film is a noose-tightening 80 minutes of masterful direction... Credit must also go to cinematographer Unax Mendia who swoops around the stage like a magician making what could be a claustrophobic film feel spacious and alive. The music by Victor Reyes is flawless and, of course, Eugenio Mira handles the proceedings like an old school master. It’s a harrowing and nail-biting piece that is well worth tuning in for."

William Bibbiani, Crave Online

"Grand Piano is the more playful cousin of Chazelle’s other script this year, Whiplash (a film he also directed), a tale of a drumming prodigy and his abusive professor that also demonstrates the horrifying relationship between antagonism and perseverance. Chazelle seems fascinated by the notion that the ends might just justify the means, and that opposition to true villainy is a prerequisite for becoming a hero. He may be right but it’s a scary message to send to sensitive art students who have probably been bullied enough already, unless schools have changed dramatically since I attended them.

"So while Eugenio Mira may be having the time of his life finding ways for Selznick to secretly call for help, and in offing one-by-one the poor saps who might be able to save him, the real drama comes not from the enjoyable but contrived set-up, but rather the way that contrived set-up highlights the ongoing struggle for self-improvement, and the simply unfortunate need to be pushed in order to push back.

"To achieve these somewhat lofty goals, Mira crescendos Grand Piano’s suspense to ludicrous heights, formulating complex shots that Brian De Palma would be proud of, and setting the climactic battle against an impromptu, bizarre and deliciously overblown performance of 'Motherless Child.' What better way to finally stop the show than with a proper showstopper?"

Robert Levin, amNew York

"In short, Grand Piano is an extended set piece with tension that starts high and remains elevated throughout. Mira's camera spins, dives and soars throughout the concert hall, ranging from POV images to steady zooms and sustained long shots, with at least one of De Palma's favored split screens thrown in for good measure. You're constantly disoriented, hyper-aware of the stakes at hand."

Scott Pierce, MoviePilot

"It's being touted as Speed or Phone Booth at a concert hall, but in reality comes across as a mostly non-violent giallo mashup inspired by visual directors like Brian de Palma, Alfred Hitchcock, and Dario Argento. It's regimented and structured in a way that few movies today are despite its kitschy premise."

Eric D. Snider, Twitch

"I don't know what Elijah Wood's actual skill level is on the piano, but the way he fakes it here is nothing short of remarkable, and it speaks to his and Mira's commitment to taking the whole thing seriously. It would have been infinitely easier to avoid showing Wood's hands as much as possible, to focus on chest-level shots where we see his arms moving but not which specific keys he's hitting. Instead, Mira gives us long, unbroken takes of Wood banging away on the keyboard, our view of his hands unobstructed so we can see that what he's playing really could be the music we're hearing. The hand-synching, if that's what you call it -- sure, let's call it hand-synching -- is nearly flawless.

"Moreover, Mira and cinematographer Unax Mendia are constantly pulling off carefully orchestrated shots and marvelous feats of camera movement, applying the same type of sweeping, operatic bravura that Brian De Palma applies to everything he does. (I thought of Snake Eyes in particular.) There's something thrilling about seeing such technical precision used in the service of such lunacy. While the screenplay (by Damien Chazelle) is overly expository and larded with repeated dialogue, everything else about the film has energy and confidence and is perfectly capable of carrying you away if you'll go along with its fantastically goofy premise."

EMPIRE's Nick de Semlyen spoke with Nancy Allen by phone recently, as the remake of RoboCop made its way into theaters. Here are some excerpts regarding the films she made with Brian De Palma:

EMPIRE's Nick de Semlyen spoke with Nancy Allen by phone recently, as the remake of RoboCop made its way into theaters. Here are some excerpts regarding the films she made with Brian De Palma:FROM JACK NICHOLSON TO 'CARRIE'

Nick: Your first movie job was The Last Detail in 1975. What was it like?

Nancy: I was with Jack Nicholson in a practical location, playing his girlfriend. And I was completely intimidated. Frozen in fear. I was originally offered the role of the hooker, which Carol Kane ultimately played so brilliantly. I called [casting director] Lynn Stalmaster and said, "You know, I don't think I can act and be naked at the same time!" I don't have any regrets about that, I must say. I think things unfold as they're meant to. But go figure, I was naked a few years later in Carrie!

Nick: How did you get that job?

Nancy: I came out to Hollywood in September of '75. In November I thought, "Well, this isn't working out" and planned to go home. But a casting director I knew from New York brought me in for the last day of casting on Carrie and said, "You won't get the part, but at least you'll meet a good director." So I went in as the last person on the last day, and got the part.

Nick: Was Carrie more fun to make?

Nancy: Absolutely. It was a magical moment in time. I couldn't believe it: a real movie and I had a real part. And Brian [De Palma] was about to break out, so that was his big moment. I don't remember being afraid on that set. The funny thing is that when I auditioned for it, it felt like do-or-die so I threw caution to the wind. John [Travolta] and I had a fabulous time working together and Brian is a great director, so I really had a great time on the movie. It spoiled me, because I thought that every movie was going to be that fun and that fabulous and that creative and that successful. I was very, very naive, because that's certainly not the case. You don't always have the right chemistry. You may make a great picture but it doesn't get the success it deserves. But Carrie was a special thing. I mean, look at the cast - everybody broke out from that movie. It was, I guess, a good thing that Brian spent so long casting the movie, because he got the right mix.

"LISTENING TO THEM DISCUSS MOVIES, IT WAS LIKE BEING IN FILM SCHOOL"

Nick: You then went on to work with Robert Zemeckis, Steven Spielberg and Brian De Palma another three times...

Nancy: I had a remarkable journey, working with incredible people. At the time, in the '70s, everyone was so young. Steven was like a boy, living in a little cabin in Laurel Canyon. He'd made Jaws, and he was just about to start Close Encounters, but he was a kid. Everyone was so young and excited. I mean, to be in that group of people on a regular basis socially, listening to them discuss movies, it was like being in film school. So I feel I was lucky. I do believe in destiny, so I think it was the path I was destined to take. I reflect back to being a teenager and I had three experiences where people tried to put me in movies and I didn't go forward with it. So I guess sooner or later it was going to happen!

Nick: 1941 was famously an out-of-control shoot. What was your experience of it?

Nancy: Oh, those were the crazy times. We had a great time for six months. It was one big party. We all loved the Zemeckis and Gale script, but once we started shooting people were walking around scratching their heads, going, "It's funny, right?" We weren't really quite sure what was going on! Tim [Matheson] and I were really lucky: our storyline was so simple and did not change or veer off course. We fared pretty well in the long run. We had a great time.

Nick: What are your bad memories?

Nancy: The underwater car stunt in Blow Out was tough. If you're claustrophobic it's a tough stunt, and I'm absolutely claustrophobic. The other time that really was a problem for me was during I Want To Hold Your Hand. I had to go under the bed in The Beatles' suite and sometimes the crew forgot I was there when they were fixing the lighting. I was not happy under there at all! Give me a gun any day, just don't put me under a bed...

Nick: Blow Out's one of my favourite films of yours...

Nancy: I loved working on Blow Out. That was just an incredible experience. It's really hard to say which is my favourite, but there are a handful I love. Carrie is special because it was my first film that I had a significant role in. RoboCop because it was so unique and original and I got to do something that there was no reason to give to me given the roles I'd done previously. And Blow Out, that was a great challenge, because I didn't particularly like the character when we started out. I wasn't supposed to do it originally, so to fall in love with that character, and to work with John [Travolta] and Dennis Franz... my God, talk about a dream come true.

According to Broadway World Cleveland, Lawrence D. Cohen is so impressed by the "rave reviews and vivid photographs" for Beck Center and Baldwin Wallace Music Theatre Program's production of Carrie the musical, that he will be in attendance Friday night, March 7, and will share his experience with both the movie and the stage show during a discussion following the performance. This will be the final weekend for the production, which plays at 8pm Friday, 8pm Saturday, and 3pm Sunday. The article states that "Lawrence D. Cohen and composer Michael Gore reached out to Director Victoria Bussert with a congratulatory note and accolades for her creativity in capturing some of the technical challenges the show presents."

According to Broadway World Cleveland, Lawrence D. Cohen is so impressed by the "rave reviews and vivid photographs" for Beck Center and Baldwin Wallace Music Theatre Program's production of Carrie the musical, that he will be in attendance Friday night, March 7, and will share his experience with both the movie and the stage show during a discussion following the performance. This will be the final weekend for the production, which plays at 8pm Friday, 8pm Saturday, and 3pm Sunday. The article states that "Lawrence D. Cohen and composer Michael Gore reached out to Director Victoria Bussert with a congratulatory note and accolades for her creativity in capturing some of the technical challenges the show presents."