AN EDWARD R. PRESSMAN TIMELINE OF SORTS

AS TONIGHT'S OSCARS PAID TRIBUTE TO PRODUCER IN MEMORIAM SEGMENT

Tonight's Oscar's broadcast included an "In Memoriam" segment in which

Lenny Kravitz, at the piano, performed his song "Calling All Angels", accompanied by guitarist

Craig Ross. The tribute included

Edward R. Pressman. A few weeks ago, I promised a followup post about Pressman, and so here it is - a sort of timeline of Pressman's first few years in the film industry.

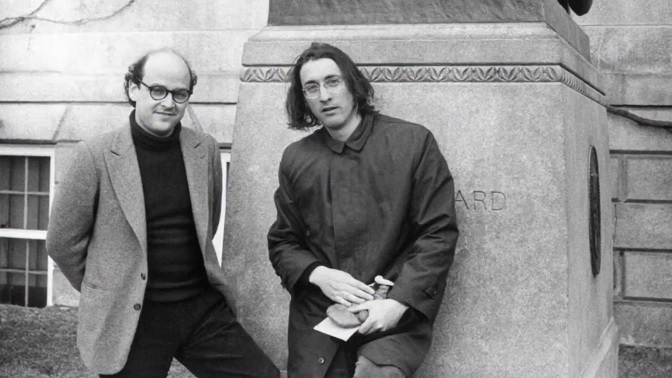

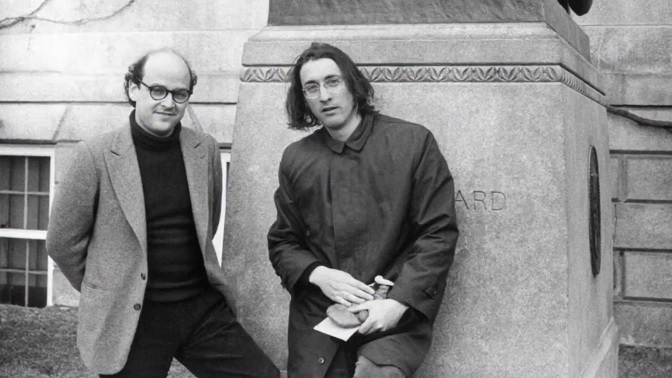

Paul Williams, from the 1973 book Directors In Action, edited by Bob Thomas:

In college I did still photography and made three short films, and wrote dozens of earnest film reviews for the school newspaper. The next year I went to England and met Edward Pressman, a young producer and philosopher. We made a short together which eventually won a Golden Eagle, which gave us the unjustified confidence to embark on our first feature film. I wrote it, Ed titled it: The Man Who Killed Men. Budgeted at five million dollars, TMWKM (as it became known) interested United Artists, but since we insisted on my directing and would not consider selling the property, United Artists explained that they couldn't have a twenty-one-year-old direct a picture of that size. I think it was Chris Mankiewicz who suggested, "Try something smaller, first." Since we didn't want to waste potential production money on a script, we decided that I should write an original. I think I wrote a simple but honest semiautobiographi- cal script about a sensitive kid in high school who never got laid. We called the movie Out of It and it took us seven months to find out that no major or minor or schlock company would finance a first feature film (a) based on a "plotless" original script about kids; (b) which called for and would use no stars; (c) to be directed by a young virgin, so to speak. "Strike three!" said Sid Kiwitt, then of Seven Arts.

Ed Pressman, a prince, to put it mildly, then privately raised 100,000 dollars which is more easily written about than done (this was before the American Film Institute, a wonderful thing, existed). In fact, it took Ed long enough to raise the bread for me to almost finish studying advanced acting and directing with Herbert Berghof and elementary techniques with Elizabeth Dillon (it was Ed's idea, based on casual observation of my short films, that I study acting).

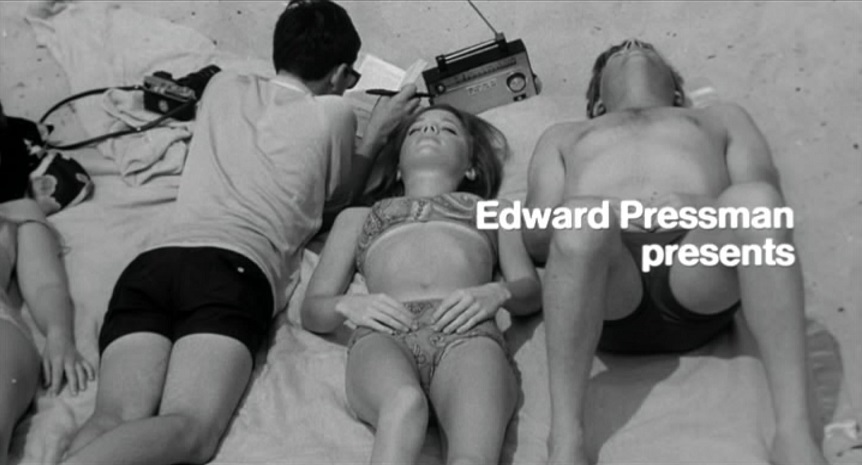

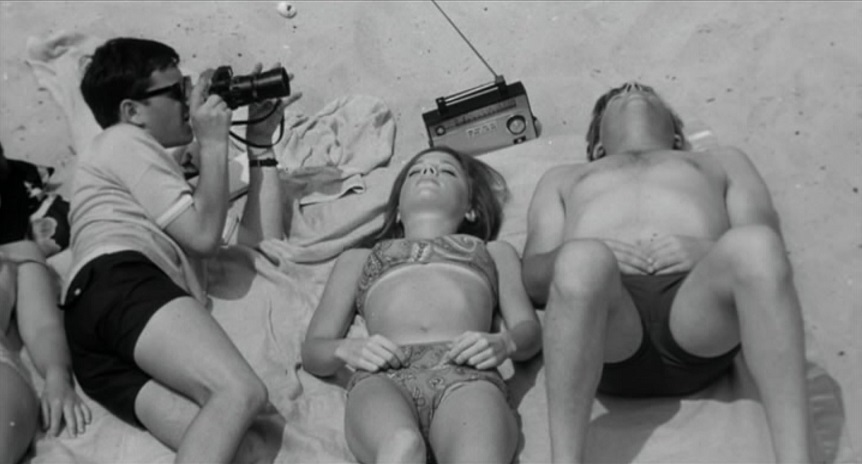

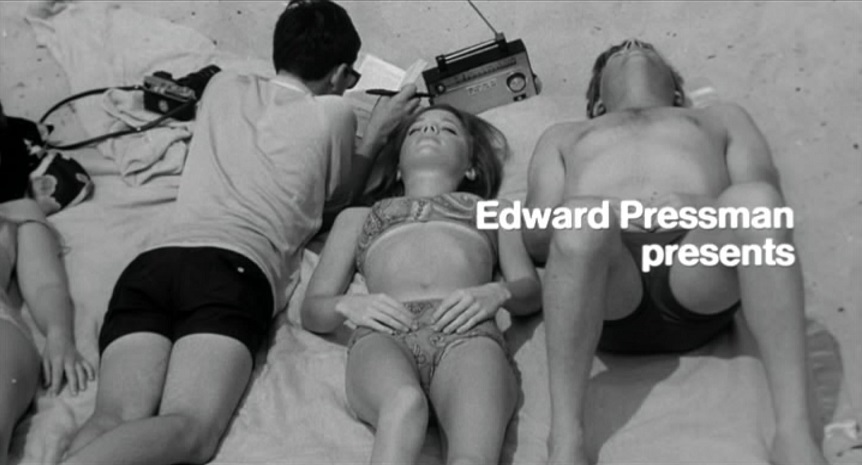

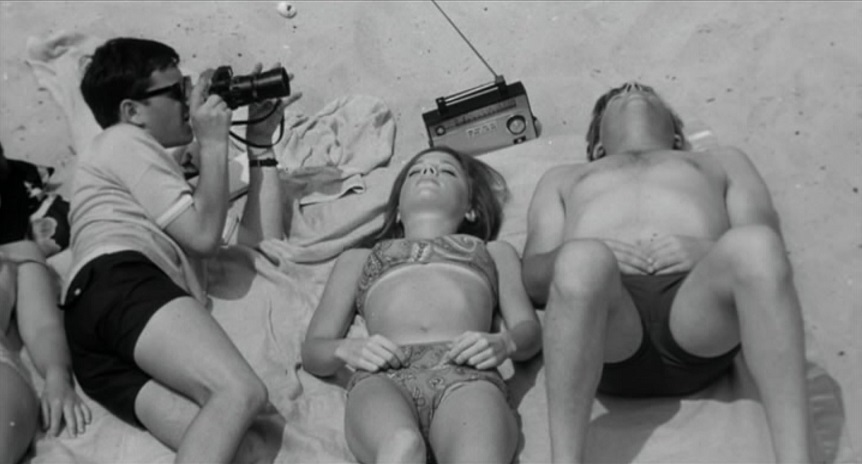

During the summer of 1967, when I was twenty-three and Ed was twenty-four, we made Out of It, starring, as the ads read now, Barry Gordon and Jon Voight. (I was knocked out when I first met Jon, told him so and have stayed that way since.) Out of It ended up costing 350,000 dollars with deferrals (everybody) and took seven weeks to shoot and ten months to edit. When David Picker of United Artists saw it. he said to Ed, "I like it. What do you want to do next?"

Making decisions daily, based so tangibly on time, heightened my awareness of categories hadn't thought adequately about before shooting. I think AFI apprentices should be required to stay in the editing room, too, as long as they don't tell anybody about what happens in there.

I had complete freedom, except for the basic economic limitations. Ed Pressman and I have had an unusual and happy professional relationship on both Out Of It and The Revolutionary. I am responsible for artistic decisions once certain perimeters are set.

On both films had final cut and final responsibility for casting, but Ed and were constantly consulting and didn't have any arguments about control or responsibility. It's hard to think of him as my producer-"partner" sounds better to me, anyway. Of course, people ask about the distributor. United Artists didn't touch a frame after they bought Out of It. They also gave me complete freedom on The Revolutionary. They are a marvelous company in that department.

IndieWire, Jul 31, 2003 - Ed Pressman Talks About 30+ Years of Producing

by Matthew Ross indieWIRE: How did you get started in filmmaking?

Ed Pressman: I really started during graduate school, when I studied philosophy at the London School of Economics. Before then, I had always loved film, but it had seemed totally remote as a career. In England, I met a young American filmmaker named Paul Williams. He was a very confident, outgoing director who had made a short film at Harvard. After a few days of talking incessantly about movies, we decided to form a partnership. We made a short together, and after that experience, everything else, compared to filmmaking, seemed so limited. At the time we started, film seemed to be a way of changing the world.

Paul was very precocious. He really gave me the confidence to get into the profession. Together he and I made films that Paul directed. The first one was a feature called “Out of It.” It was Jon Voight‘s first film, and John Avildsen was the cameraman. We shot it for about $200,000 at my folks’ summer house in Atlantic Beach, using credit cards and small investments. At the time, that method of making a film without distribution already in place was very, very rare. Cassavetes was doing it and that was about it; the studios really made the movies. But we made the film and sold it to David Picker, who was running United Artists. He then gave us a three-picture deal. We were 21 at the time, and it all seemed so simple. It was a great experience right off the bat. Unfortunately, that film was held back from release because right after United Artists bought it Jon was signed up to star in “Midnight Cowboy,” and they wanted to wait until after that movie was done to get our film some visibility. The next film Paul and I made was “The Revolutionary,” which starred Jon Voigt and Robert Duvall.

iW: How did your partnership with Paul work out?

Pressman: We worked together for about eight years. Paul directed three films, the last of which was “Dealing: Or the Berkeley-to-Boston Forty-Brick Lost-Bag Blues,” based on a book by a young writer named Michael Crichton. Then we started to produce films with other directors. We made “Badlands” with Terrence Malick and “Sisters” and “Phantom of the Paradise” with Brian de Palma. A lot of young filmmakers used to hang out at our office, including Brian and Martin Scorsese, because Paul was really one of the first directors of our generation to make it. Then he went on a spiritual trip. He gave up all his possessions, split up with his wife, and left filmmaking. He’s since come back, and he’s made some interesting low-budget films over the past few years; but it’s hard to get back into the groove after you’ve been gone for so long.

When he went away, he sold his interest in the partnership to me, and I went out on my own. The next time I had a partnership was when I started ContentFilm with John Schmidt two years ago.

In conversation with

Samuel Blumenfeld and

Laurent Vachaud, De Palma said that Pressman "notably produced

Phantom of the Paradise and

Terrence Malick's first film,

Badlands. I met Ed when I was in Los Angeles. Martin Ransohoff had refused to do

Sisters, and I had just bought the screenplay from him! When he read it Ed immediately wanted to do it. He managed to find enough money, two hundred thousand dollars, to get the movie started. Then he continued fundraising while filming, and the budget eventually came to six hundred thousand dollars." As De Palma explained to Blumenfeld and Vachaud, Pressman-Williams was the production company Pressman had created with Paul Williams, who was not the songwriter who plays Swan in Phantom, but the "director of two films with Jon Voight. The Revolutionary and Out of it."

Pressman was an integral part of making those films with Williams, and continued that sort of passion with the films he went on to make with De Palma. "Ed's parents had a toy company," De Palma continued, "Pressman Toys, one of whose offices was located at 23rd Street and Broadway. Pressman-Williams had set up its headquarters there. I was working in their offices after the disaster of Get To Know Your Rabbit, and Paul Williams was still a director working at Warner whose film Dealing ended in disaster. Dealing was adapted from the first novel by Michael Crichton. He had written it with his brother Douglas when they were students at Harvard."

Ed Pressman on Mystic & Severe Radio, July 27, 2020

Brian was a friend from New York, and he’d done a film called Greetings, and Hi, Mom!, which were low-budget, very independent movies. And I was a fan and a friend. And Brian then went on to do a studio movie called Get To Know Your Rabbit at Warner Bros. And he had a very unhappy experience. He called me and said, “I’ve got these two projects under option to Warners that I’d do anything to get out.” And, you know, asked if I could find a way to get the properties free. And we were able to do that, and then we had Sisters and Phantom Of The Paradise, and decided, not because of …. [too much occurred? Absurd?] … but because it was simpler to start with Sisters. And we worked with a team of actors and friends who all knew each other from Margot Kidder to Jennifer Salt, Brian and Chuck Durning. So there was an immediate ability to bring it together and do the film for a low budget. And the film opened fairly weakly, but then at that time, there were drive-in theaters. And the drive-in theaters did very substantial business all of a sudden, so it just took on a life that, you know, wouldn’t have existed without the drive-in audience, which was more exploitational. So we did that, and then started to do Phantom Of The Paradise with the same company that distributed Sisters. I remember two weeks before we started to shoot Phantom, they asked to cut the budget by five million dollars, and we couldn’t see a way to do that. So we were fortunate enough to meet an independent financier and Gus Berne and partner Gabe Katzka, who, by a great piece of luck, agreed to come in and take over the financing of the film. So we did it independently, and sold it to Fox after it was made, which at that time was not a common thing.

Ed Pressman, 2012 interview about Badlands:

There were a lot of naysayers, doing the film. I remember the initial line producer, who I had worked with on another film, was let go because he didn’t get along with Terry. And he went back to New York and told my mother, who was really helping me finance the movie, that this film was a mess, and don’t waste your money on this. My gut told me to believe in Terry. And I think that was a good lesson.

March 2023 article abouyt Lynn Pressman at Queens HistoryLynn Pressman Raymond was born Lynn Rambach in Woodhaven in 1912. As she grew older, her family moved to Brooklyn where she was a standout at Erasmus Hall High School in Flatbush. As a young woman, she began her career in sales and marketing by rising through the ranks of various stores (including Abraham & Straus) as a publicist. Eventually, her talents caught the attention of James McCreery & Co., a fashionable department store on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan, where she soon found herself in charge of publicity.

But her true calling was the acquisition of toys and games and she found herself drawn to positive and educational products. She also found herself drawn to Jack Pressman, who owned a toy and game company and earned the nickname “The Marble King” because of how many marbles he purchased to supply all the Chinese Checker games that he sold.

In 1942, they married and as vice president of Pressman Toys, Lynn Pressman developed a toy that made a fortune and still sells in stores to this day. She developed the children’s toy doctor bag as a way to ease the fear that children felt when visiting the doctor.

It came with toy versions of doctor’s tools (stethoscope, thermometer and a syringe) and a small bottle of candy pills. The doctor’s bag was a runaway success, leading to variations such as a nurse bag and even versions for Ken and Barbie.

Her husband’s health made it necessary for Lynn Pressman to take an even more active role running Pressman Toys and upon his passing in 1959, she assumed control. She was, at the time, one of the very few women executives running a large company.

This led to issues getting credit, even from the bank her husband had done business with for years, but she eventually secured credit and overcame all obstacles to become one of the more powerful women executives in the United States.

She was a pioneer in licensing the rights to popular television and movie characters for use in creating toys, creating games based on Disney characters along with Superman and the Lone Ranger. She was also known for licensing athletes and creating games using their likenesses on the packaging.

When she took over Pressman Toys, she made one major change to the company policy that undoubtedly impacted the bottom line. Lynn Pressman stated that her company would no longer manufacture, market or sell any toy guns or rifles to children.

Keep in mind that this was the early 1960s and toy guns and rifles were big sellers, but from that moment on, her company followed this principle.

Ms. Pressman, an outspoken opponent of the war in Vietnam, worked together with peace organizations in the late ’60s to encourage other companies to refrain from making “toys that symbolize destruction.”

Through her relationship with UNICEF, she developed a line of Pen Pal Dolls, based on Walt Disney’s Small World attraction at the World’s Fair. Each doll came with a pen and paper and information about the doll’s country.

Later in life, she enjoyed a second career and a bit of enjoyable notoriety through her son, Edward. In fact, Lynn Pressman is listed in the credits as a co-producer of Phantom of the Paradise, directed by Brian De Palma. Lynn Pressman also served as an extra in several of her son’s films.

[From the Scream Factory interview with Edward R Pressman (2002)]

Phantom was pretty inclusive. We were financing the film, we were using our family’s toy factory to shoot the film, and we were present throughout the shooting in Dallas and New York. You know, a time I try to enjoy the most, when I’m most involved. It’s easy to be removed and be more of an executive, but at that time I was very integral in the process. A person who is never recognized for her help in making the film was my mother, Lynn Pressman. Because Lynn Pressman ran Pressman Toy Company, my family toy company. And she allowed and encouraged us to use the factory for the prison scene, and the scene in the record pressing plant. There was a moment of terror when the machine seemed to be actually almost crushing Bill’s head… fortunately, it didn’t. But Lynn’s help in letting us use the factory in the prison scene and the record scene, and generally helping us finance the movie, with the help of Gus Berne and Gabe Katzka… If there’s one person who I’ve never really recognized for helping this movie, it was Lynn.

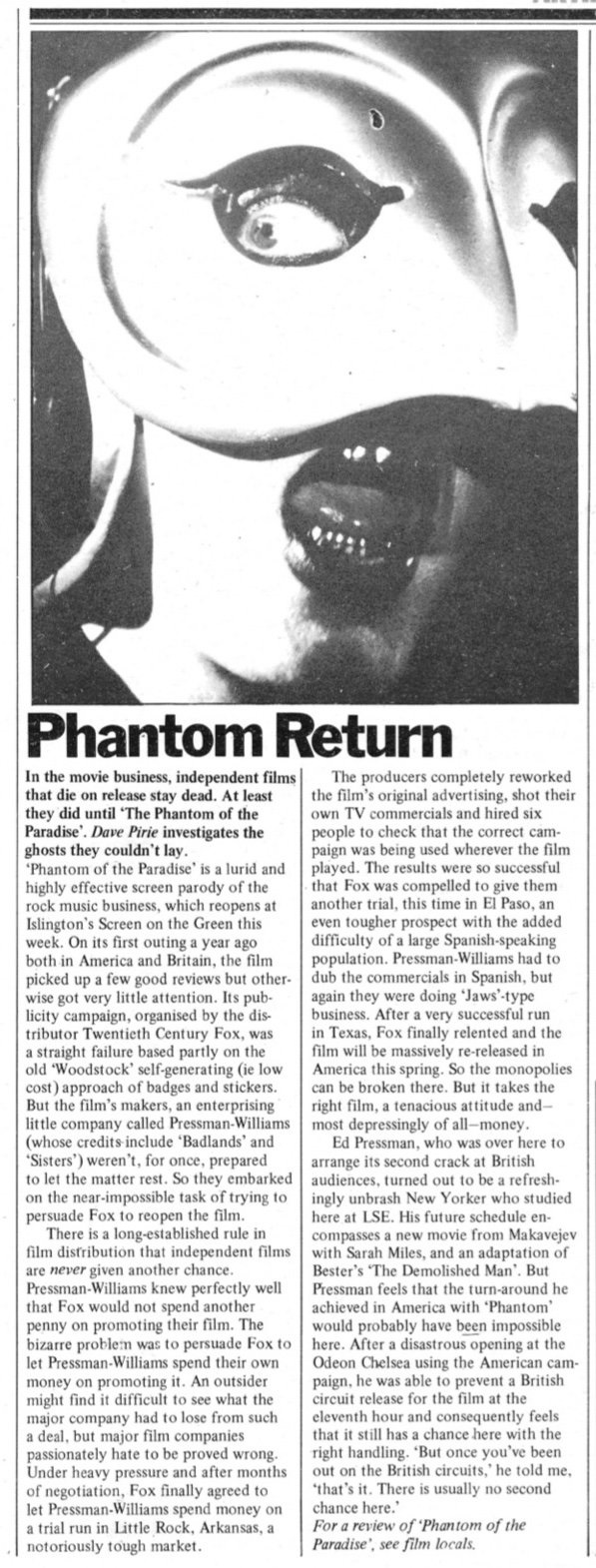

From Ed Pressman 2012 interview about BadlandsIronically, after the Warner Brothers release of Badlands, which was a failure, we did re-release the film, maybe six years or eight years later. And we arranged our own distribution in Little Rock, Arkansas, which was the least expensive television market. So we could make ads and promote the film on television with modest means. And then we went to Memphis and did the same thing, and then to Dallas. And once the film was proven in Dallas, then Warner Brothers re-released the film. We had proven that the film could do business. We did the same three-city model with Phantom Of The Paradise, with Brian De Palma’s film, a few years later. And at that time, you could kind of distribute the films yourself. …

After Phantom came out – Sisters, Badlands, Phantom – those films were all, in one way or another successful, either artistically or business-wise, Fox came to us and offered us a deal to pay our overhead and give us a development fund. And so we thought, that’s great, and we took the deal. And that was the most unproductive period of my life, because we worked at a studio and management changed after we made the deal. So the new management was, I think Daryl Zanuck came, and he didn’t want to do any things we wanted to do. So we spent two or three years not making movies. You know, had offices, and had money to develop things, but we weren’t making movies. So after that I decided I’d rather take my chances and stay independent and get the films made, even if it was not as comfortable.

The Maverick Producer - 1987 New York Times article by Thomas CarneyON AN EARLY SUMMER EVENING IN 1973, Ed Pressman found himself in an apartment on Manhattan's Upper East Side, celebrating the engagement of his thrice-widowed mother, Lynn, to a stockbroker. There he met Gustave Berne, an energetic real estate tycoon in his 70's who had also dabbled in the movie business. Pressman was soon telling Berne about a problem he was having with his sixth movie, ''Phantom of the Paradise,'' a Faustian legend set in the world of rock music. American International Pictures had agreed to finance the project, which Brian De Palma would direct. But A.I.P. had suddenly cut the budget in half. ''I don't know whether they're just squeezing us,'' Pressman said, ''or if Sam Arkoff has changed his mind.''

Berne studied Pressman for a moment. ''I think we can do something, Eddie,'' he said. ''Let's meet tomorrow for lunch.''

Berne checked out the 30-year-old producer and the next day, when Pressman showed up at the Italian Pavilion, Berne boomed out: ''You're O.K., kid. Let's make a deal.''

Pressman's new partner came up with $900,000, the bulk of the ''Phantom'' budget. They estimated the overage - the amount necessary to insure that a movie will be completed even if the budget runs over - at $200,000. That became Pressman's responsibility.

Ed Pressman was an unlikely recruit for the movie business. The son of Jack Pressman, a toy executive known in the 1930's as the Marble King, he appears to have passed smoothly from one play world into another, bringing with him a universe of contacts not often available to those in the film industry.

Pressman's father had died when Ed was 16, and his mother took over the family concern, the third-largest maker of board games in the United States. But Pressman did not want to spend his life dreaming up games for Pressman Toys. As a boy in New York, he worked the refreshment stand at the Lane movie theater, owned by his uncle, Morris Lane. After graduating from Stanford University, he had spent a year at the London School of Economics - but for days hung around the London offices of Columbia Pictures. ''I went into film for the same reason I majored in philosophy,'' he says. ''They are both world-encompassing subjects.''

With $5,000, Pressman bankrolled Paul Williams, another young American abroad, to make a 12-minute short called ''Girl,'' which won a 1966 Golden Eagle Award for nontheatrical films. Back in New York, Pressman confessed to his mother with characteristic understatement why he had overdrawn his bank account: ''Mother, I did this film, and it won an award. And I'd like to go into the movie business.'' In 1969, the novice producer tested his mother's generosity once again when he failed to get studio backing for his first feature-length film, ''Out of It,'' also written by Paul Williams. Lynn Pressman gave her son not only most of the $225,000 he needed but also the run of her summer house on Long Island as a location to shoot the movie. ''I learned to be a producer just by jumping in and doing it,'' says Pressman. ''I was very skeptical about film school. With 'Out of It' I did everything, from the catering on.'' Pressman sold the completed film to United Artists for $250,000. He and Williams then took the check and laid it on Pressman's mother's desk at Pressman Toys.

Over the next five years, the two men made ''The Revolutionary,'' ''Dealing,'' ''Sisters'' and ''Badlands.'' This was the era of ''Easy Rider,'' when studio production heads were willing to take a chance on emerging talent. Williams was the wild-haired young genius while Pressman, prematurely bald, with his calm, deliberate air, seemed older, the stable businessman. Williams eventually stopped making movies, but the early alliances he and Pressman forged with such film writers and directors as Brian De Palma and Oliver Stone were to have lasting importance for Pressman's career. For altogether different reasons, the partnership with Gus Berne also proved a memorable experience. When ''Phantom of the Paradise'' was finished in 1974, 20th Century-Fox bought the film for $2 million. That seemed to assure Pressman and Berne a tidy $800,000 profit. Then Universal enjoined the movie, claiming that ''Phantom of the Paradise'' was a remake of their film ''The Phantom of the Opera.''

''It wasn't. It was a parody,'' says Pressman, ''but we settled the suit out of court, at a cost to Berne and myself of about $350,000."

Ed Pressman quote from 1989 interview in AustraliaMost of the films are the work of a single writer-director—the expression of a single vision. As I like to say, the work of John Milius in Conan The Barbarian is as valid in its way as Brian De Palma in Sisters. They’re very different, but they’re all, at least to me, original, cinematically, and somehow tied to the currents of the time.