Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | March 2023 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

| 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 |

| 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | |

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

There’s nothing exceptionally strange about a big star setting up a production company - the likes of Margot Robbie and Brad Pitt have them these days. With Cruise, though, it’s always helpful to look a little deeper.Tom Cruise is a control freak. It’s one of his defining attributes. Just about every role he would pick from here on out would be to cultivate a very particular image of himself. For a period of time in the 2000s, when uncomfortable attention was resting on his public persona, it’d become very obvious that Cruise was using his roles to actively push back on how people saw him (we have a lot to talk about with Mission III). This control is necessary. It’s how he survives. Naturally, just being the star wasn’t enough for him.

Production helped him get into all aspects of the creative process, to shape his star vehicles from top to bottom, to make sure it was all part of the ongoing Cruise Project. Cruise was still collaborating with top auteurs - three years after this, he’d knock two of the biggest working directors out in a year - but these projects would gradually dry up as his producer era solidified, and he was pretty much done with all that by the mid-2000s. Not coincidentally, this pretty much lined up exactly with the end of his appearances in supporting roles. On a Tom Cruise project, he’s the star, or he’s not in it at all.

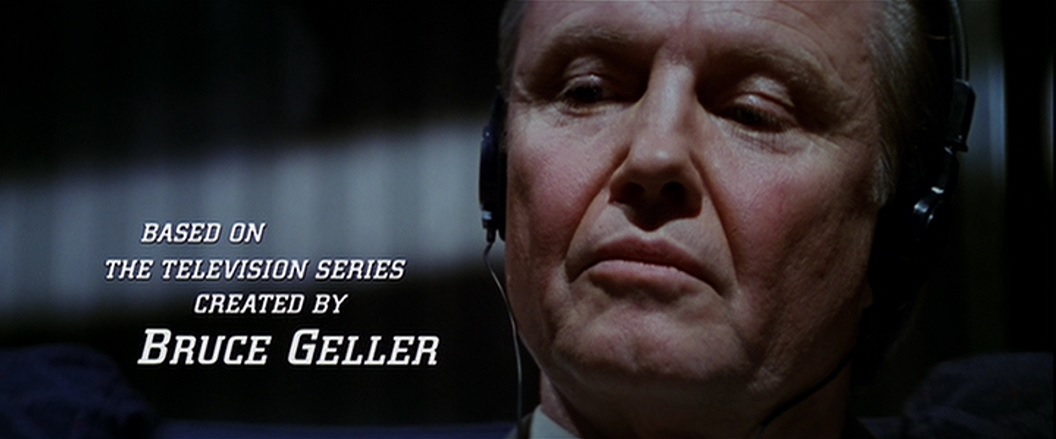

Naturally, then, you’d have to conclude two things from a Cruise-produced Mission: Impossible. First, that he’d lead it. Second, that because the lead of Mission: Impossible is Jim Phelps, so surely Cruise would be Phelps.

Hmm, though. Phelps was a pre-existing character whose actor had portrayed him for nine seasons of TV and stepping into someone else’s well-established role is hardly Tom’s speed. Moreover, Phelps wasn’t a young character - Peter Graves, when he signed off the role in 1989, was 64. If the movie was going to be a continuation of the show (and in the event, it was), then there’s no way Cruise could be a 64-year-old dude. If there’s one thing Tom Cruise abhors, other than antidepressants, it’s seeming old. In 2017’s The Mummy, he is described as a “young man”.

So, no to Cruise as Phelps. In the event, they cast age-appropriate Jon Voight, now most famous for being a weird right-wing crank on Twitter, and Cruise found an elegant solution to the lead-problem: he simply created a new self-insert hero character and made him the centre of the entire story.

Ethan Hunt was born. His first act, like many sons, was to murder who came before him and take his place.

From here on out, pretty much, Tom Cruise picks the directors.

One might assume from his established control freakery that Tom would want pliable journeymen directors who can serve his will - a Jaume Collet-Serra or Shaun Levy type. The fun thing is, though, his tastes for Mission: Impossible were generally quite the opposite. The pattern of Mission: Impossible’s auteur era, the sequence of four movies all handled by vastly different directors, is that Cruise finds someone interesting and lets them cook - at the very least in the early going. The man has layers.

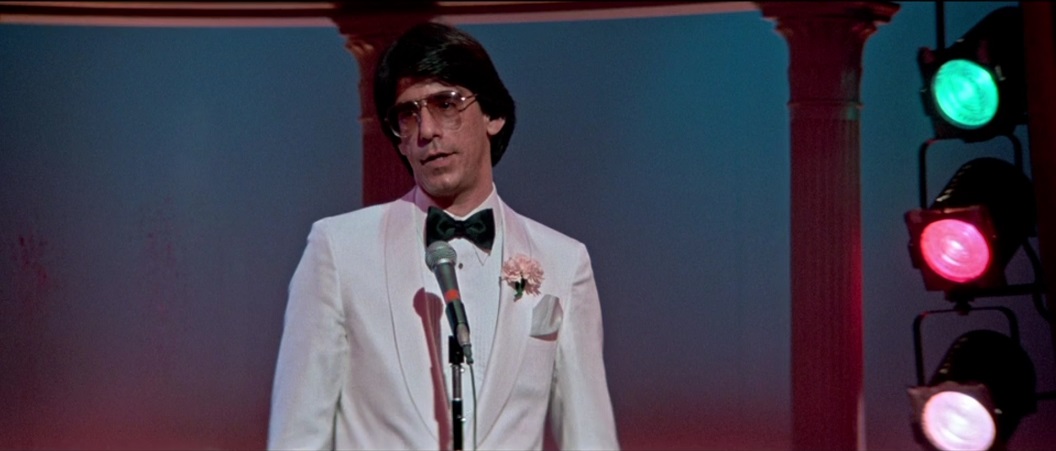

First at bat is Brian De Palma, a choice that I assume seemed somewhat odd at the time. De Palma had been working in Hollywood for nearly three decades, directing movies that I guess you could call successful. Carrie? Scarface? Blow Out? Seen them?

(I haven’t, by the way. Don’t look at me like that. You shouldn’t have expected any better of me.)

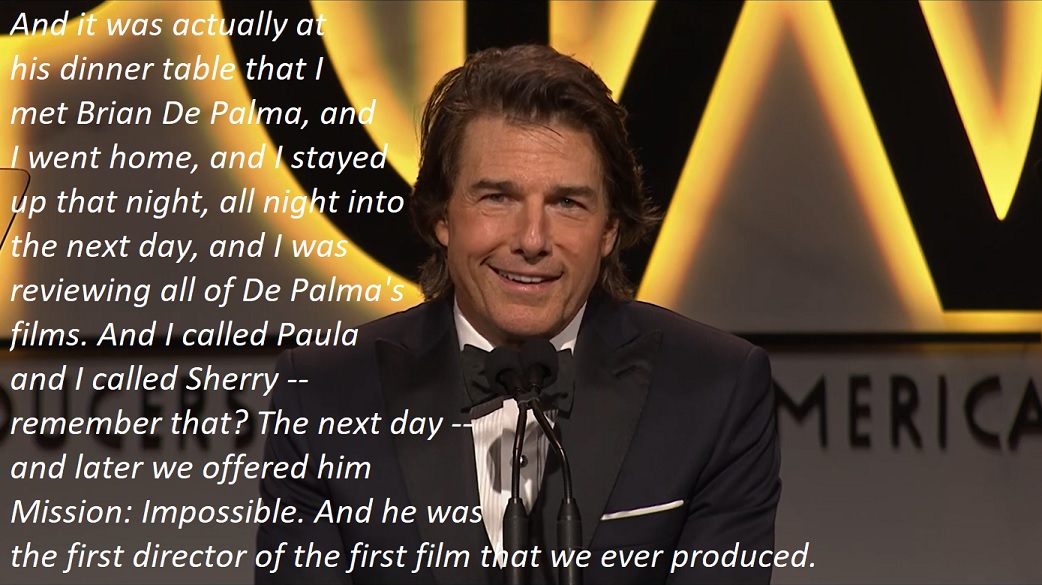

Befitting Cruise’s new big tycoon guy status, he found De Palma in an appropriately glitzy way - through their mutual buddy Steven Spielberg. Heard of him?

Spielberg, at this point, was in one of the hottest phases of his career, having directed Jurassic Park and Oscar-winning Schindler’s List in the same year just a couple of years beforehand. It wouldn’t be until the next decade/century/millennium that the two of them would work together, but when they got to it, they would cook quite nicely.

Anyhow, the Mission script zagged through the typewriters of some of Hollywood’s biggest screenwriters under De Palma’s direction. There were three credited writers on the final script, and the combined prestige of them could have killed a medieval peasant - David Koepp had co-written Jurassic Park (and would later go on to have a truly odd career including Spider-Man, Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull and the Cruise The Mummy reboot that will haunt this newsletter later), Robert Towne had written Chinatown and Cruise/Tony Scott vehicle Days of Thunder, and Steve Zaillian would later write two Martin Scorsese movies.

We’ll put a pin in Mission screenwriters now, but suffice to say: some weird guys have gotten their hands on these scripts.

It should be noted that, ten years on from Top Gun, Cruise was going into the main action role of his career, one which would span three decades, in his mid-thirties. That’s not unprecedented, and nor would it be seen as an aberration - Robert Downey Jr., for instance, debuted as Iron Man aged 43. It’s also true that Ethan Hunt is a bit of a move forward from the “young hotshot” archetype that Cruise brought to Top Gun - there is a conscious acknowledgement that this is not the same guy.

Still, it’s as good an indicator as any of how intrinsic eternal youthfulness will become to Cruise’s public (and, you suspect, self) image in later years. If Ethan Hunt is the kind of role that would be a breakout for most actors in their twenties, then, well, that’s just how Tom Cruise sees himself: whatever age he really is, he believes that he’s younger.

The funny thing is, I wrote all of that before rewatching Mission: Impossible, and the thing I had forgotten was that the movie really does begin with Jim Phelps as the leading guy. The first 15 minutes - a suspenseful heist sequence that’s stylish as hell - are a condensed version of what I imagine a classic M:I episode to have been. You have the video briefing, a little team banter, and then the mission. Jim Phelps is the leader. He gets the mission. He’s the main guy.

Tom Cruise, on the other hand, is introduced as just a member of the ensemble - obviously the wisecracking cool one, who stands out among the archetypes of “snarky tech guy”, “posh British lady”, “Jim Phelps’ trophy wife” and “Hannah”, but still one amongst many. He’s what TV Tropes would call a Canon Foreigner, an original creation for the film, but he slots neatly and without fuss into the existing Mission framework headlined by Phelps. He knows his place.

Then everybody on the team fucking dies except Tom Cruise. He runs around the streets of Prague in a tuxedo, sweating, as he watches the entire cast of Mission: Impossible, including Jim Phelps, die brutally. By 25 minutes, only he remains. The lone survivor. I mean, it’s a great opening. Establishing a status quo and knocking it out from under our feet before the first act is even done? That’s De Palma magic. It is, also, a subtextual minefield, knowing what we know about Tom Cruise.

Really, it’s difficult not to read a movie in which he graduates from side character to lead and then takes over the front man role and builds his own team of supporting characters as a kind of commentary on the way Cruise insists on doing things.

And it was actually at his dinner table that I met Brian De Palma, and I went home, and I stayed up that night, all night into the next day, and I was reviewing all of De Palma's films. And I called Paula [Wagner] and I called Sherry—remember that? The next day—and later we offered him Mission: Impossible. And he was the first director of the first film that we ever produced.

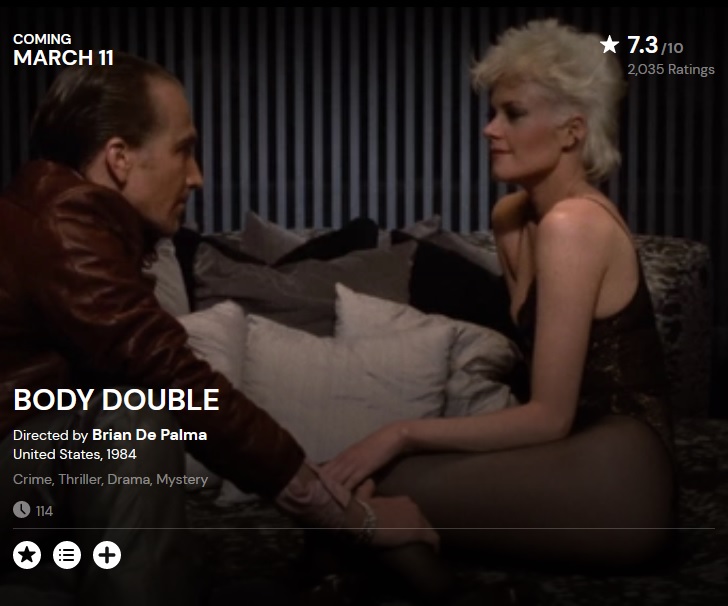

Here's MUBI's take on Body Double:

One of the most divisive auteurs out there takes the floor! The sublime and the sleazy hold hands in his work, intertwining to a point in which they become masterfully indiscernible. Body Double is pure De Palma joy: both irreverent and reverential, a sexy, stylish, twisted ode to Hitchcock.

Mom was the most important person in my life. When I was 10, in 1976, she took my brother and me to see ‘Obsession,’ a movie that wasn’t especially age-appropriate. It’s about a guy whose wife and daughter are kidnapped. The rescue fails and his wife dies. The guy believes his daughter died, too, but she disappeared. Years later, he meets and falls in love with a young woman who looks just like his wife. It turns out to be his daughter. Yeah, I know. A fast track to therapy. But I was more captivated by the film’s acting and storytelling, so much so that I knew then what I wanted to do with my life.

In the interview portion of the article, Irvin tells Bonilla that the book, the first in a series of memoirs, covers his life/career up until the time he met Brian De Palma. "And then, for 2024," Irvin says, "I will do the next volume of my ongoing series of memoir books, this one covering my De Palma years."

In the interview, Irvin talks about why the journal he had writen for the magazine Cinefantastique was never published:

Why did you stop publishing Bizarre?The reason I stopped doing it, is that I ended up meeting Brian De Palma and had to start getting serious about figuring out a career in film. Between my junior and senior years of college, I ended up going to work for De Palma on The Fury. After I graduated, I became a full-time employee of De Palma as his assistant.

Then, I associated produced and was a production manager for his film Home Movies with Kirk Douglas and Nancy Allen. That's what launched my career.

When did you decide to step away from magazine writing to focus on your film career?

I became friends with Fred Clark, who was the editor of Cinefantastique. When I was working on The Fury, I got an assignment from Fred to write a journal on the making of The Fury. I still wanted to be writing for about horror movies and stay in that world.

Fred promised that The Fury would be on the cover. So, I interviewed everybody on the film from Kirk Douglas down, including composer John Williams and the editor Paul Hirsch, who edited Star Wars. Then, Fred saw Star Wars. He decided to bump our issue, so he could do a double issue on Star Wars. Okay, fine. Star Wars deserved it.

In the meantime, I insisted to Fred that, “You've got to run my interview with Amy Irving. You can't wait, because she talks about for the very first time ever, her relationship with Steven Spielberg. They were living together and it had not been revealed anywhere. I have this huge scoop.

What was the result?

So, Fred assured me that he’d run the Amy interview in the Star Wars issue, as kind of a teaser for the big coming issue on The Fury. Then, The Fury opens. Fred sees it, hates it, and decides that he is not going to put it on the cover. He cuts my journal on the making of it in half and on the cover, he instead puts the composer Hans Salter, who composed some of the scores of the 1940s Universal horror movies. I love Salter and his scores, but could there be anything less commercial? It felt like such a slap.

De Palma was not happy, and I was embarrassed. It made me look bad. I felt really bad about the whole thing.

It put such a bad taste in my mouth, that when I got asked to do articles on other films that I was working on, like Dressed to Kill, I just ended up turning it down. It kind of extinguished my wanting to continue to be a journalist in that realm. Instead, I focused on being a director.

These characters make Marlowe personal for Jordan. He’s a protégé of visionary director John Boorman, and movies are central to his imagination. Hawks’s cherished melodrama of mid-20th-century sexual intrigue is reinterpreted in terms of the history and nomenclature of film noir; revealing not only the characters’ erotic drives but their sin-sick environment. This ’30s Hollywood is morally dubious, centered on the clash of power, sex, and other vices, seen through Jordan’s literary-cinematic sensibility. Clare, evoking the Old World county and a tarnished version of Saint Clare of Assisi, confers the genre’s ultimate, poetic judgment on the story’s villain: “Because he was far too young for me. Because he was evil incarnate. Because he was already dead.”Jordan’s Catholic-manqué Marlowe is incomprehensible without prior knowledge of Hawks’s convoluted film (symbolized by Marlowe pursuing a victim-suspect through a labyrinthine mausoleum) and, especially, Altman’s Chandler update (starring Elliot Gould) and Polanski’s mix of both Chandler and Dashiell Hammett archetypes. So this is an art film. Jordan does literary puns on Christopher Marlowe and profane riffs on James Joyce. (Dorothy knew Joyce and recalls him as a literary thief and “syphilitic little man.”) This isn’t disrespect so much as a leveling. Marlowe is Jordan’s look at cultural cynicism, linking Joyce to Chandler and to the many Dr. Faustuses of Hollywood itself.

All Jordan can do is reexamine that heritage — sordid intimations of incest, Evelyn Mulwray’s blasted eye socket in Chinatown, Gould-Marlowe’s betrayed friendships — to signify our cultural decay more effectively than Damien Chazelle did in Babylon. Jordan arrives at the same moral juncture that Brian De Palma faced in The Black Dahlia, finding the essence of modern miasma in the delusions of Hollywood’s past. For an ethnic-focused film artist like Jordan, this would include new Hollywood’s race and gender hypocrisy.

Trendy, vapid Chazelle sentimentalized a token Mexican immigrant in Babylon, but Jordan and waggish co-screenwriter William Monahan, who scripted Scorsese’s The Departed, plays with ethnicity (those Irish mugs, Lange’s perfect brogue, and Cumming’s perfect Southern twang). Daring the same black/Irish tease of The Crying Game and Mona Lisa, Jordan effects a coup, inserting the experience of black chauffeur Cedric (British-Nigerian actor Adewale Akinnuoye-Agbaje, Oz’s Adebisi), evoking both Native Son and A Raisin in the Sun. A burly outsider like Marlowe, Cedric knows the inside track, summing up Hollywood as “a city of motorized secrets.”

At first, the rapprochement of Marlowe and Cedric resembles the gimmicky violent bonding of Butch and Marsellus in Pulp Fiction. But because Jordan is a serious cinema aesthete, their brotherhood pinpoints Hollywood’s moral hypocrisy as it moved into World War II propaganda. Cedric looks at the backlot fakery of Nazi book-burning and daringly opines: “Still, that Leni Riefenstahl; she made some good movies, though.” It may be the ultimate clapback at modern Hollywood’s corrupt double standard. Detective Jordan rescues movie mythology.

In a The Hollywood Reporter obituary, Chris Koseluk writes that Belzer found "further fame as the cynical but stalwart detective John Munch on Homicide: Life on the Street and Law & Order: Special Victims Unit." Koseluk continues:

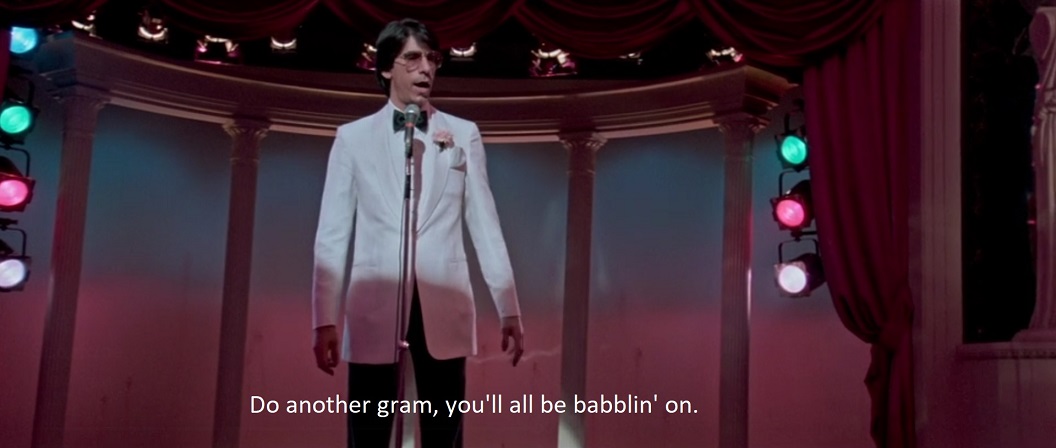

Belzer died early Sunday at his home in Bozouls in southwest France, writer Bill Scheft, a longtime friend of the actor, told The Hollywood Reporter. “He had lots of health issues, and his last words were, ‘Fuck you, motherfucker,'” Scheft said.Belzer made his film debut in the hilarious The Groove Tube (1974), warmed up audiences in the early days of Saturday Night Live and famously was put to sleep by Hulk Hogan.

Munch made his first appearance in 1993 on the first episode of Homicide and his last in 2016 on Law & Order: SVU. In between those two NBC dramas, Belzer played the detective on eight other series, and his hold on the character lasted longer than James Arness’ on Gunsmoke and Kelsey Grammer’s on Cheers and Frasier.

Certainly one of the most memorable cops in TV history, Munch — based on a real-life Baltimore detective — was a highly intelligent, doggedly diligent investigator who believed in conspiracy theories, distrusted the system and pursued justice through a jaded eye. He’d often resort to dry, acerbic wisecracks to make his point: “I’m a homicide detective. The only time I wonder why is when they tell me the truth,” went a typical Munch retort.

In a 2016 interview for the website The Interviews: An Oral History of Television, Homicide executive producer Barry Levinson recalled listening to Belzer on The Howard Stern Show and liking him for Munch. “We were looking at some other actors, and when I heard him, I said, ‘Why don’t we find out about Richard Belzer?” Levinson said. “I like the rhythm of the way he talks. And that’s how that happened.”

When Richard Belzer did stand-up on “Late Night With David Letterman,” he always entered to the opening riffs of “Start Me Up” by the Rolling Stones, dancing his way onstage, looking like the life of the party in dark shades. Once he arrived at the microphone, he made a point of engaging with the studio audience in a way you rarely saw on television. More than once, he asked, “You in a good mood?” and waited for a cheer. Then his tone shifted: “Prove it.”With that opening pivot, he turned the relationship between comedian and crowd upside-down. The expectation was now on the people in the seats: Impress me.

Belzer, who died Sunday, is best known for his performances as a detective on TV, but his acting career was built on a signature persona in comedy, as a master of seductive crowd work who set the template for the MC in the early days of the comedy club. Often in jackets and shirts buttoned low, he cut a stylish image, spiky and louche. He could charm with the best of them, but unlike many performers, he didn’t come off as desperate for your approval. He understood that one of the peculiar things about comedy is that the line between irritation and ingratiation could easily blur.

Throughout the 1970s, he ran the show at the buzziest of the New York clubs: Catch a Rising Star, stand-up’s answer to Studio 54. He roasted the crowds while warming them up, quizzing them about where they were from and what they did, establishing rapport and dominance. Long before Dave Chappelle dropped the mic at the end of shows, Belzer regularly did so.

If the crowd wasn’t laughing, he could lay on a guilt trip: “Could you be a little more quiet? Because I’m going to have a nervous breakdown.” And if someone heckled, look out. According to a story from the comic Jonathan Katz, one night someone in the crowd yelled, “Nice jacket!” and Belzer responded that he got it on sale in his mother’s vagina.