There’s nothing exceptionally strange about a big star setting up a production company - the likes of Margot Robbie and Brad Pitt have them these days. With Cruise, though, it’s always helpful to look a little deeper. Tom Cruise is a control freak. It’s one of his defining attributes. Just about every role he would pick from here on out would be to cultivate a very particular image of himself. For a period of time in the 2000s, when uncomfortable attention was resting on his public persona, it’d become very obvious that Cruise was using his roles to actively push back on how people saw him (we have a lot to talk about with Mission III). This control is necessary. It’s how he survives. Naturally, just being the star wasn’t enough for him.

Production helped him get into all aspects of the creative process, to shape his star vehicles from top to bottom, to make sure it was all part of the ongoing Cruise Project. Cruise was still collaborating with top auteurs - three years after this, he’d knock two of the biggest working directors out in a year - but these projects would gradually dry up as his producer era solidified, and he was pretty much done with all that by the mid-2000s. Not coincidentally, this pretty much lined up exactly with the end of his appearances in supporting roles. On a Tom Cruise project, he’s the star, or he’s not in it at all.

Naturally, then, you’d have to conclude two things from a Cruise-produced Mission: Impossible. First, that he’d lead it. Second, that because the lead of Mission: Impossible is Jim Phelps, so surely Cruise would be Phelps.

Hmm, though. Phelps was a pre-existing character whose actor had portrayed him for nine seasons of TV and stepping into someone else’s well-established role is hardly Tom’s speed. Moreover, Phelps wasn’t a young character - Peter Graves, when he signed off the role in 1989, was 64. If the movie was going to be a continuation of the show (and in the event, it was), then there’s no way Cruise could be a 64-year-old dude. If there’s one thing Tom Cruise abhors, other than antidepressants, it’s seeming old. In 2017’s The Mummy, he is described as a “young man”.

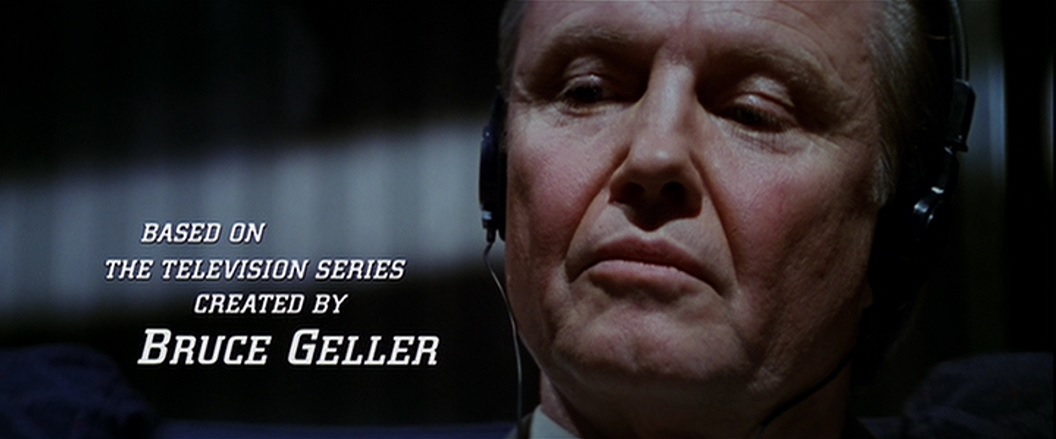

So, no to Cruise as Phelps. In the event, they cast age-appropriate Jon Voight, now most famous for being a weird right-wing crank on Twitter, and Cruise found an elegant solution to the lead-problem: he simply created a new self-insert hero character and made him the centre of the entire story.

Ethan Hunt was born. His first act, like many sons, was to murder who came before him and take his place.

From here on out, pretty much, Tom Cruise picks the directors.

One might assume from his established control freakery that Tom would want pliable journeymen directors who can serve his will - a Jaume Collet-Serra or Shaun Levy type. The fun thing is, though, his tastes for Mission: Impossible were generally quite the opposite. The pattern of Mission: Impossible’s auteur era, the sequence of four movies all handled by vastly different directors, is that Cruise finds someone interesting and lets them cook - at the very least in the early going. The man has layers.

First at bat is Brian De Palma, a choice that I assume seemed somewhat odd at the time. De Palma had been working in Hollywood for nearly three decades, directing movies that I guess you could call successful. Carrie? Scarface? Blow Out? Seen them?

(I haven’t, by the way. Don’t look at me like that. You shouldn’t have expected any better of me.)

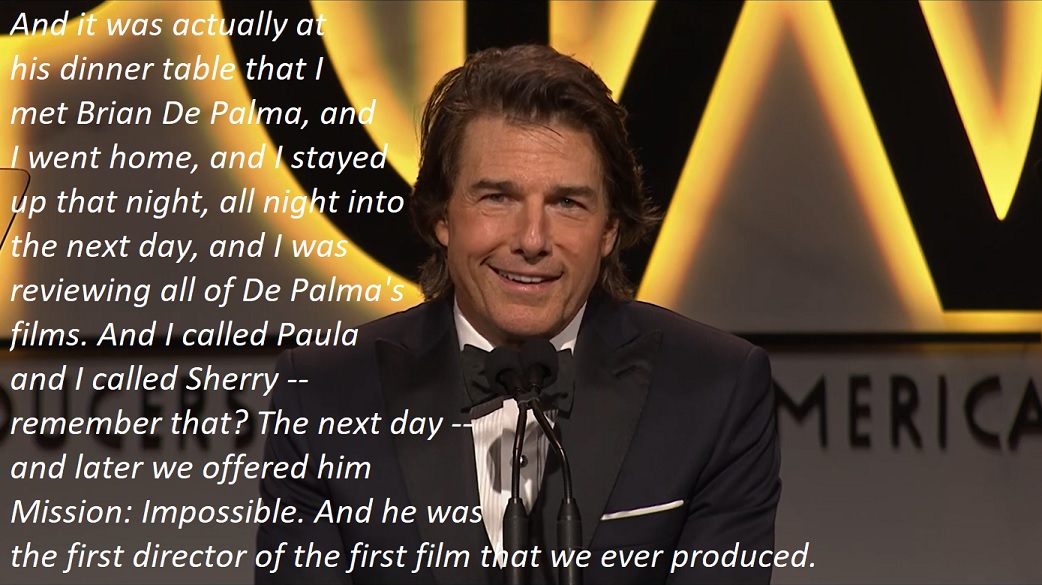

Befitting Cruise’s new big tycoon guy status, he found De Palma in an appropriately glitzy way - through their mutual buddy Steven Spielberg. Heard of him?

Spielberg, at this point, was in one of the hottest phases of his career, having directed Jurassic Park and Oscar-winning Schindler’s List in the same year just a couple of years beforehand. It wouldn’t be until the next decade/century/millennium that the two of them would work together, but when they got to it, they would cook quite nicely.

Anyhow, the Mission script zagged through the typewriters of some of Hollywood’s biggest screenwriters under De Palma’s direction. There were three credited writers on the final script, and the combined prestige of them could have killed a medieval peasant - David Koepp had co-written Jurassic Park (and would later go on to have a truly odd career including Spider-Man, Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull and the Cruise The Mummy reboot that will haunt this newsletter later), Robert Towne had written Chinatown and Cruise/Tony Scott vehicle Days of Thunder, and Steve Zaillian would later write two Martin Scorsese movies.

We’ll put a pin in Mission screenwriters now, but suffice to say: some weird guys have gotten their hands on these scripts.

It should be noted that, ten years on from Top Gun, Cruise was going into the main action role of his career, one which would span three decades, in his mid-thirties. That’s not unprecedented, and nor would it be seen as an aberration - Robert Downey Jr., for instance, debuted as Iron Man aged 43. It’s also true that Ethan Hunt is a bit of a move forward from the “young hotshot” archetype that Cruise brought to Top Gun - there is a conscious acknowledgement that this is not the same guy.

Still, it’s as good an indicator as any of how intrinsic eternal youthfulness will become to Cruise’s public (and, you suspect, self) image in later years. If Ethan Hunt is the kind of role that would be a breakout for most actors in their twenties, then, well, that’s just how Tom Cruise sees himself: whatever age he really is, he believes that he’s younger.

The funny thing is, I wrote all of that before rewatching Mission: Impossible, and the thing I had forgotten was that the movie really does begin with Jim Phelps as the leading guy. The first 15 minutes - a suspenseful heist sequence that’s stylish as hell - are a condensed version of what I imagine a classic M:I episode to have been. You have the video briefing, a little team banter, and then the mission. Jim Phelps is the leader. He gets the mission. He’s the main guy.

Tom Cruise, on the other hand, is introduced as just a member of the ensemble - obviously the wisecracking cool one, who stands out among the archetypes of “snarky tech guy”, “posh British lady”, “Jim Phelps’ trophy wife” and “Hannah”, but still one amongst many. He’s what TV Tropes would call a Canon Foreigner, an original creation for the film, but he slots neatly and without fuss into the existing Mission framework headlined by Phelps. He knows his place.

Then everybody on the team fucking dies except Tom Cruise. He runs around the streets of Prague in a tuxedo, sweating, as he watches the entire cast of Mission: Impossible, including Jim Phelps, die brutally. By 25 minutes, only he remains. The lone survivor. I mean, it’s a great opening. Establishing a status quo and knocking it out from under our feet before the first act is even done? That’s De Palma magic. It is, also, a subtextual minefield, knowing what we know about Tom Cruise.

Really, it’s difficult not to read a movie in which he graduates from side character to lead and then takes over the front man role and builds his own team of supporting characters as a kind of commentary on the way Cruise insists on doing things.