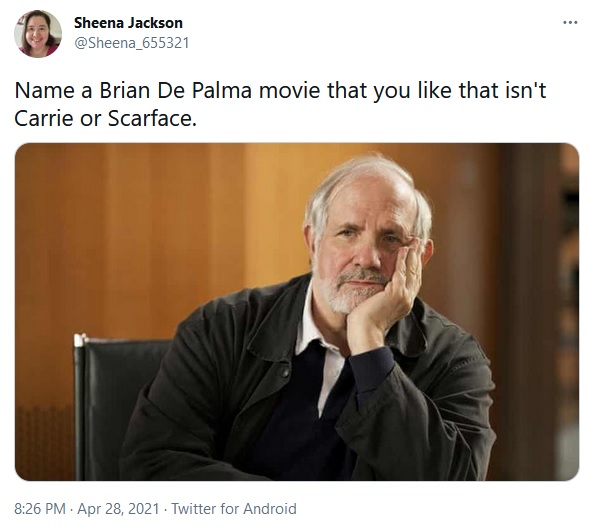

PEOPLE WERE DISCUSSING BRIAN DE PALMA FILMS LAST WEEK

Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | May 2021 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | ||||||

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 |

| 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 |

| 30 | 31 | |||||

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

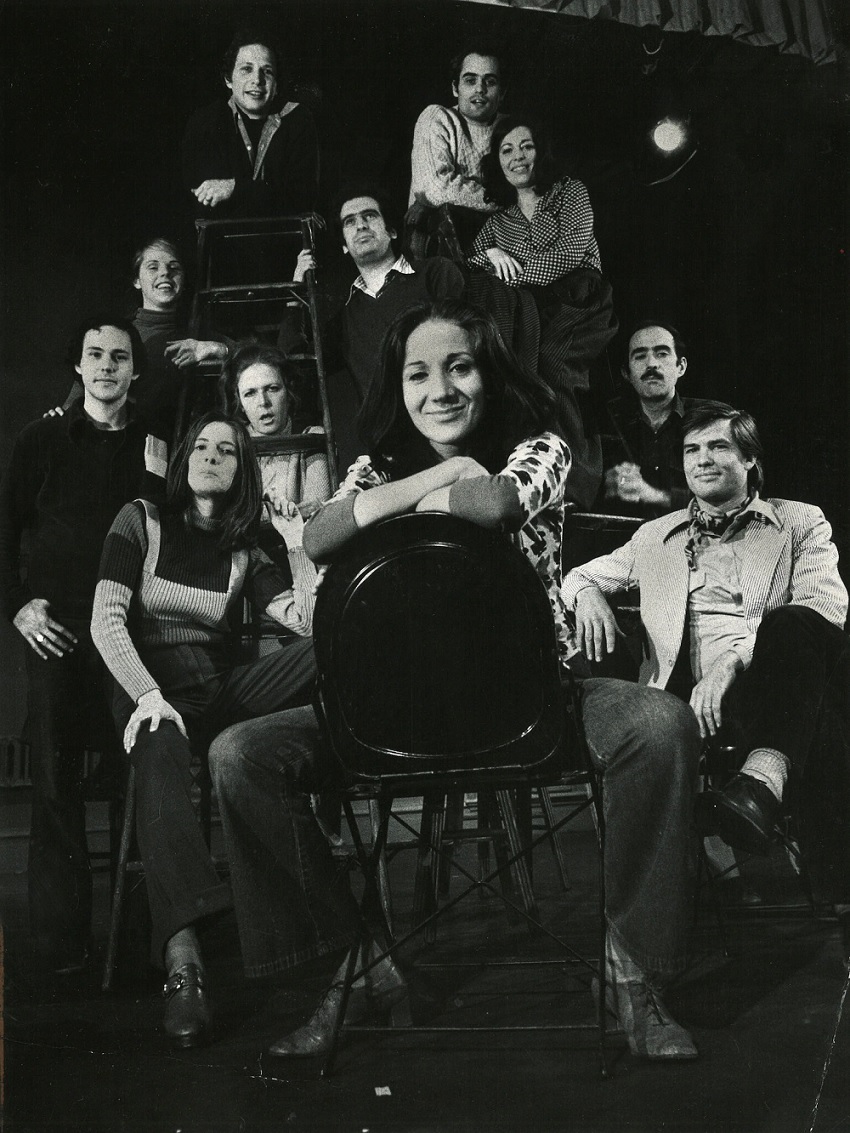

Sisters was made in 1973, the same year that Dukakis and her husband, Louis Zorich, helped found the Whole Theater Company in Montclair, New Jersey (the first photo below, dated from 1973, shows Dukakis in the front chair with the rest of the company). In Sisters, Phillip is running errands for Danielle when he spots the 4 Corners Bakery, and asks the worker inside to decorate a birthday cake with the names Dominique and Danielle. The lady turns her head back to Dukakis, telling her this guy wants her to write names on a cake. "I'd like to see you try!" Dukakis scoffs back at her, and the co-worker take it as a challenge (and we get a classic eerie suspense queue from Bernard Herrmann). Later, as Grace begins investigating Phillip's murder, she stops at the shop with her mother, and asks the lady about the cake. The lady cannot even remember the names she wrote on the cake(!) but, even during a busy moment, Dukakis pulls herself into the conversation to say the she remembers the names: Dominique and Danielle.

Excerpt from a 2003 New York Times brief by Margo Nash about Dukakis promoting her autobiography:

The trim 72-year-old actress with the throaty voice and direct manner has appeared in more than 40 films, 100 plays and 26 television movies. She has played parts ranging from her Oscar-winning role in 1987 as Cher's mother in ''Moonstruck,'' which made her famous, to the transsexual landlady in television's ''Tales of the City'' and ''More Tales of the City.'' She has also directed, taught acting, helped found five theaters, including the Whole Theater, and won numerous awards.She and her husband, Louis Zorich, were Manhattan theater actors when they moved to Montclair in 1970, seeking a peaceful place to raise a family. They also wanted to start their own theater company, and so with other acting couples, founded the Whole Theater.

The company's first play was ''Our Town,'' in 1973. For the next 17 years, the theater produced five plays a season, including the works of Pirandello, Euripides, Eugene O'Neill, Samuel Beckett, Tennessee Williams, Edward Albee, Lanford Wilson and many others, in productions that were critically praised. Among the actors performing were Jose Ferrer, Colleen Dewhurst, Blythe Danner and Samuel L. Jackson, as well as Ms. Dukakis and Mr. Zorich.

Excerpt from New York Times obit by Anita Gates:

Olympia Dukakis was born on June 20, 1931, in Lowell, Mass., the older of two children of Constantine and Alexandra (Christos) Dukakis, both Greek immigrants. Her father worked in various settings, including a munitions factory, a printing business and the quality control department of Lever Brothers. He also founded an amateur theater company.Olympia graduated from Boston University with a degree in physical therapy and practiced that occupation, traveling to West Virginia, Minnesota and Texas during the worst days of the midcentury polio epidemic. Eventually she earned enough money to return to B.U. to study theater.

Even before she received her M.F.A., she threw herself into her new career, making her stage debut in a 1956 summer stock production of “Outward Bound” in Maine. She moved to New York in 1959 and made her New York stage debut the next year in “The Breaking Wall” at St. Mark’s Playhouse.

Her first screen appearance came in 1962, on the television series “Dr. Kildare.” Her first movie role was an uncredited one as a psychiatric patient in “Lilith” (1964). She received an Obie Award in 1963 for her role as Widow Begbick, the canteen owner, in Bertolt Brecht’s drama “A Man’s a Man” and another, 22 years later, for playing the grandmother of Mr. Durang’s character in “The Marriage of Bette and Boo.”

Along the way she married Louis Zorich, a fellow actor who had appeared with her in a production of “Medea” in Williamstown, Mass. Together they helped found the Whole Theater Company in 1973 in Montclair, N.J., where they lived while bringing up their children. The company produced the likes of Chekhov, Coward and Williams for almost two decades. Ms. Dukakis also taught acting at New York University.

The film certainly embraces all the carnage and bloodshed (Michael B. Jordan gets one hell of a last stand towards the climax that brings to mind Brian De Palma’s Scarface), but it’s also not endorsing the rationale that brings him to these predicaments.

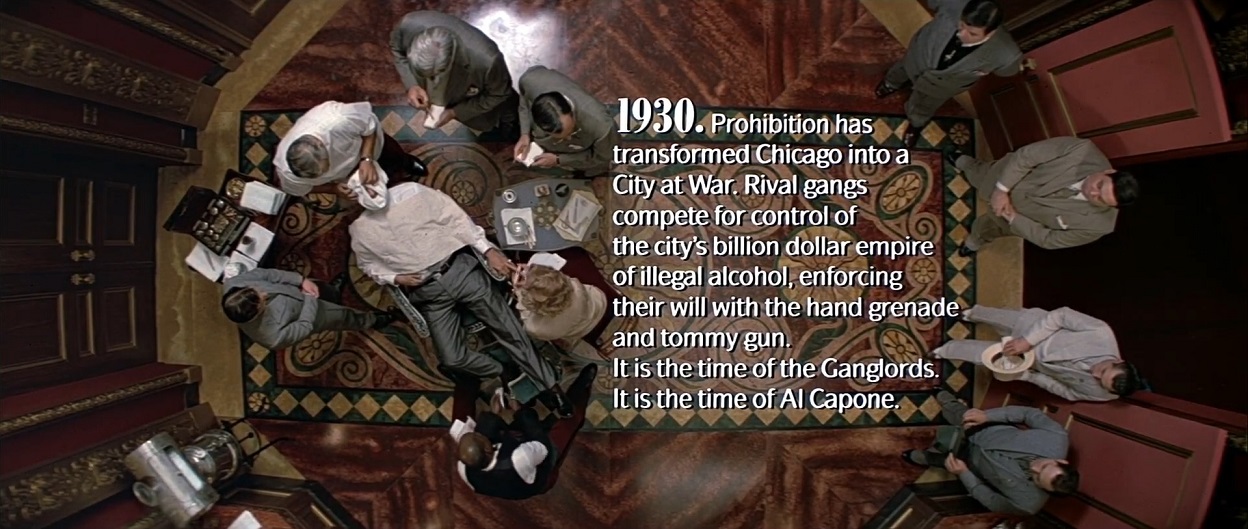

It’s rare that an original movie and its remake are both great films. But such is the case with “Scarface,” in both its 1932 and 1983 incarnations. It would be a fun double bill or, better yet, these films would best be watched on consecutive nights.What’s good about seeing both over a short period of time is that the films inform each other. In the original, Paul Muni plays an Italian, but not a real Italian — more like a kabuki Italian. Al Pacino plays a similarly exaggerated Cuban. The violence of the 1983 version tells us how the 1932 film was perceived in its time: It was considered one of the most violent films to date. And both movies deal tangentially, but unmistakably, with what it’s like to be an immigrant in America.

I prefer Brian De Palma’s 1983 version – it’s a beautifully vulgar masterpiece – but an equal case could be made for the Howard Hawks original. Watch both and decide for yourself.

This three-hour Cinema DNA lecture/discussion, led by Robert C. Cumbow, will examine a few of the films that owe the greatest debt to Vertigo and have done the most to honor its continuing place in film culture. Among the films to be discussed-in passing or at length-are works as diverse as Chris Marker's landmark short film La Jetée and his feature-length meditation on memory, Sans Soleil, which works in part as a commentary on the staying power of Vertigo; Brian DePalma's Obsession; Robert Aldrich's The Legend of Lylah Clare; Francois Truffaut's Mississippi Mermaid; Christian Petzold's stunning Phoenix; and several others. Some of the films will be represented by selected clips. There may be an occasional spoiler; but whether you have seen all, some, or only a few of the many films influenced by Vertigo, come and join the discussion, and expand and enrich your appreciation of the power that Hitchcock and Vertigo brought to the cinema.

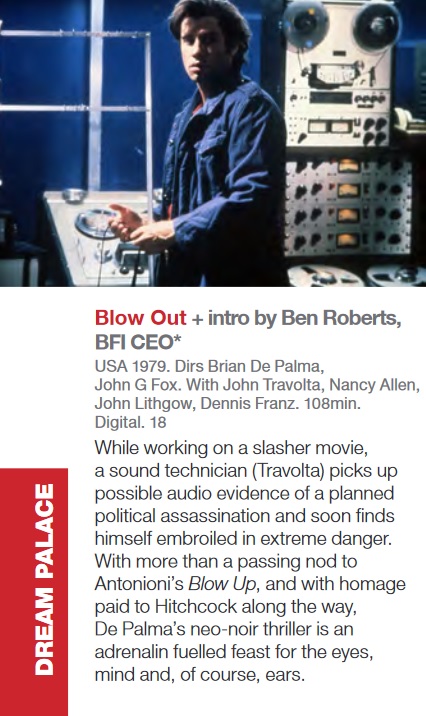

The pandemic has been traumatising on so many levels. One of the positives of the lockdown experience was a sense of communities supporting one another. We’ve been hearing from a rising tide of people who are missing going to the cinema, despite the speculative media narratives around whether or not the global pandemic would be the death of movie-going – something of a wearisome ‘old chestnut’ for some of us. It’s okay to love watching films at home, and thank goodness for streaming platforms – how would we have got through the pandemic without them? Being a movie-lover does not require us to enter a binary state that pits streamers against cinemas. BFI Player is full of amazing films and you can watch them all for a fiver a month. It’s not one or the other, it can be both, it can be all. Such was the sentiment around the inevitable impact of COVID-19 upon cinemas, that we witnessed a positive, heartfelt call to arms from the film community. Edgar Wright listed his 40 favourite cinema experiences for Empire magazine, and our own editorial campaign in Sight & Sound, ‘My Dream Palace’, celebrated the form and our venues. It’s a series of love letters to cinemas from an extraordinary cohort of cinema luminaries, designed to celebrate and ‘keep a light burning’ for cinemas while they’re closed. We all want to be back sitting in the dark together, feeling these stories become dreams on the big screen. We want to be back in our ‘safe harbours’, to borrow Mark Cousins’ phrase, and now we can be. The following is a selection of films chosen by participants of our Dream Palace campaign, and some BFI extended family. We asked people to select the film that they would most like to see at BFI Southbank – and what a selection it is! A wonderfully eclectic mix to look forward to. One thing’s for sure, they’re all going to be glorious to see on our dreamy big screens.

From a TIME magazine article by Richard Corliss, June 22, 1987:

Dawn Steel, president of production at Paramount, recalls that Mamet's first draft was an "outline, very sparse." How sparse? Capone was hardly in it. To flesh out Mamet's bare-bones script, Steel and her boss Ned Tanen wanted De Palma. "In the past," she says, "Brian hasn't chosen the material that was worthy of him and that he was worthy of. He was making homages to Alfred Hitchcock. This one is a homage to Brian De Palma -- he felt it instead of directing it. With this picture he became a mensch." It surely marked a ! change from the snazzy, derivative thrillers (Carrie, Body Double) and dope operas (Scarface) that made him notorious. The new picture would be neither parody nor eulogy; it would be the story of a straight arrow, told with a straight face.There are the familiar De Palma touches: lots of photogenic blood, a gorgeous tracking shot that leads our heroes from euphoria to horror, an endlessly elaborate set piece reminiscent of the Odessa Steps sequence in Potemkin. But the director's chief contribution is to the film's handsome physical design. "I wanted corruption to look very sleek," he says. "Some people in positions of power with ill-gotten money insulate themselves with over-the-top magnificence. They buy paintings and expensive clothes. And deep inside they know they're cheats and killers."

Visual Consultant Patrizia Von Brandenstein (Amadeus) accompanied De Palma to Chicago to devise the film's production design. "I thought about these four unlikely little guys going up against the mythic monolith of Capone," she says. "So I used architecture that showed mass and power: the Chicago Theater for the opera house, Louis Sullivan's Auditorium Building for Capone's hotel, a spiffed-up Union Station for the Odessa Steps sequence. Fortunately, Paramount let me really run wild."

I get hung up on this stuff, too, though it’s easy to easy to overlook the lies, narrative or visual, for other compensations. “The Untouchables,” for example. Director Brian De Palma and Chicago-born screenwriter David Mamet filmed a lot of their 1987 Eliot Ness/Al Capone saga here, at Union Station, or on the Michigan Avenue bridge over the Chicago River.Factually the film is full of it, and I don’t mean facts. It makes stuff up. (It’s a fictional narrative based a little bit on fact; in other words, not a documentary.) At one point, Mamet bailed on rewrites ordered up by producer and fellow Chicago native Art Linson involving Ness tossing gangster Frank Nitti off a rooftop.

It’s a pretty dumb scene, but “The Untouchables” has many I love. Some take glorious advantage of filming here, in the city where the story is set, as in the simple establishing shot of Kevin Costner, Sean Connery, Andy Garcia and Charles Martin Smith crossing LaSalle Street, backed by the 44-story wonder that is the Chicago Board of Trade Building. That famous corridor has never been given grander screen treatment, with the possible exception of “The Dark Knight.”

Chicago as an authentic 20th-century screen entity has a sadly incomplete history, largely thanks to Richard J. Daley. In 1957, NBC-TV premiered the Chicago-set police drama “M Squad,” starring Lee Marvin as the tough guy who, decades later, inspired Frank Drebin in “Police Squad!” and the subsequent “Naked Gun” movies.

Daley and then-Police Commissioner Timothy O’Connor had no love for it. In their eyes, “M Squad” made Chicago look bad. A 1959 epsoide depicted a cop on the take, which made Daley vow never to make special accommodations for outside film crews. That same year, Marvin told TV Guide: “We shoot locations, twice a year. No permit, no cooperation, no nothing. They don’t want any part of us .… Any public building, but nothing else, no stopping traffic. We shoot it and blow.”

A decade later “Medium Cool,” with its culminating scenes filmed during the downtown Chicago melee during the August 1968 Democratic National Convention, gave the city and the mayor another image problem. Daley let John Wayne and “Brannigan” film here, in the mid-’70s, but only when the Jane Byrne mayoral years commenced did Hollywood feel welcome and free to take over Chicago’s streets and beat things up a little, the way the 1980 smash-‘em-up “The Blues Brothers” did.

“Judas and the Black Messiah” may not give you any of the real or period-approximated Chicago of the Fred Hampton years, but Cleveland turned out to be a reasonably effective substitute. Oddly, it’s “The Trial of the Chicago 7″ that looks and feels more fraudulent in terms of atmosphere, even though Sorkin filmed some scenes here.

Moral of the story? You never know. Filming “Holidate” here wouldn’t have saved “Holidate.” And, though I love it, the Chicago-set and Chicago-filmed “Widows” apparently had just enough script issues and knotty storylines to prevent it from connecting with the mainstream audience it deserved.

We’ll close with a little-known story behind the Union Station sequence in “The Untouchables.”

At the time, cultural historian [Tim] Samuelson was working for the Commission on Chicago Landmarks, helping with location scouting for De Palma’s crew. They needed, as he recalled, “a building that looked like a 1920s hosptial with a lot of stairs in front of it, plus a landing.”

Samuelson told them about a couple of churches he knew, here and there. Those might work, he said. How about a church instead of a hospital? No, doesn’t fit the script, the crew said. Well, the only other place, really, is Union Station, Samuelson replied.

A day or two later: “Thanks a lot,” one of the production liaisons told Samuelson, laughing. “Thanks to you, we had to rewrite the whole (expletive) script!” And that’s the scene we have today, filmed on the steps of our beautiful downtown train station, the only possible location for such a preposterously effective homage to the Odessa Steps sequence in Sergei Eisenstein’s “The Battleship Potemkin.”

It never really happened. It’s fiction. But you know? Who cares?

From James Southall's 2013 review of Ennio Morricone's Untouchables soundtrack, via Movie Wave:

De Palma has always believed that music has a very important role to play in a film and as such, the scores for his films tend to be striking and very much at the forefront; and he’s worked with some wonderful composers including Bernard Herrmann, Pino Donaggio, John Williams, Ryuichi Sakamoto, Danny Elfman and others. On three occasions, he worked with the great Ennio Morricone.The first of those was The Untouchables (with Casualties of War and Mission to Mars to follow in later years) and Morricone’s up-front, arresting music is quite brilliant. The score opens with “The Strength of the Righteous”, which introduces the main action theme (one of five major themes in the score), as electronic beats accompany a repeating five-note phrase heard on low-end piano and then strings, all with a wailing harmonica accompaniment. It’s a portentous opening to film and score – particularly dark yet somehow wonderfully colourful as well. Interestingly, of all the great melodic themes in the score he could choose from, when he performs the music in concert it is this dark action piece that Morricone chooses. The harmonica theme without the five-note accompanying figure is heard in the brilliant-but-brief “In the Elevator”. “The Man with the Matches” is another reprise of the material, this time filled with even more tension (and on the extended version of the album, appended with the brief “Nitti Shoots Malone”, adding a brilliant piece of anguished string writing to the end of the piece). The previously-unreleased “Courthouse Chase” is a brilliant variant on the material, on this album providing a good introduction to the familiar “On the Rooftops”, the score’s primary action cue.