Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | May 2021 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | ||||||

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 |

| 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 |

| 30 | 31 | |||||

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

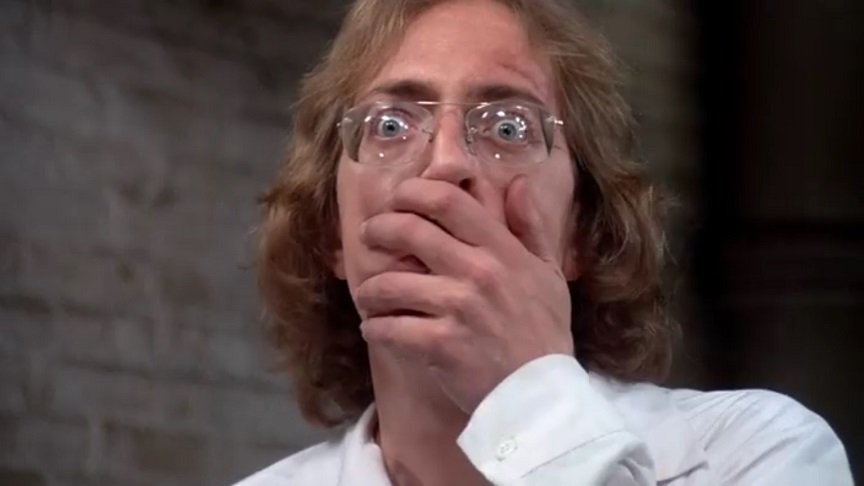

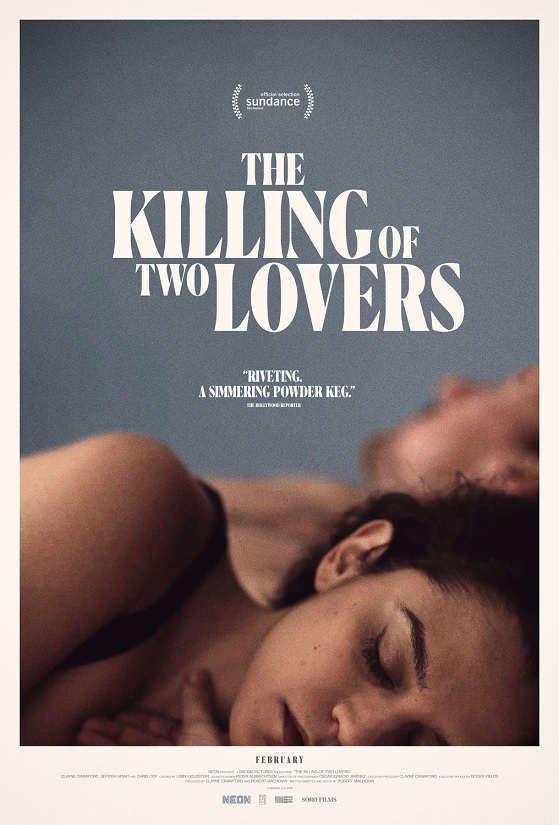

The Killing of Two Lovers writer-director Robert Machoian thought a lot during the planning of the film about “how to shoot long takes without drawing attention to the fact that it’s a long take, in and of itself.”So he went back and watched Brian De Palma’s Snake Eyes for its flashy 12-minute single take opening.

“It’s very showy. And there’s a place for that. But for this film, it would have been very inappropriate to be showy at all,” he says.

The Killing of Two Lovers follows married couple David (Clayne Crawford) and Nikki (Sepideh Moafi) in rural Utah, as they work through a separation. But after Nikki gets a boyfriend (Chris Coy), David begins to unravel.

The film makes masterful use of long takes throughout, and Machoian and cinematographer Oscar Ignacio Jiménez employ it much differently than De Palma did for his Nicolas Cage conspiracy thriller. In one key moment, the camera acts as an equalizer during an emotionally fraught scene.

Avoiding traditional shot-reverse-shot coverage, the camera is instead framed on both David and Nikki as they work through an argument. This prevents the audience from choosing a side.

“The second you hold the camera, you establish that somebody is more important than the other,” Machoian explains. “But David and Nikki are equally trying to figure this out. And there really isn’t one who is in more of a position of power than the other.”

Crawford, Moafi, and Coy all have theater experience, which made pulling off these extended sequences possible. “If we didn’t have the actors that we had, we would have had to shoot it differently. Because if you do a long take with someone who can’t act, it just gets worse the longer they go with it — it doesn’t necessarily get better,” Machoian says.

Machoian is aware that long takes can be distracting to viewers.

“It felt really important to just orchestrate the performance, and allow Sepideh and Clayne to move within that frame, and as a result, hopefully not draw attention to the fact that we’ve been sitting on this shot for four minutes,” he said. “Hopefully in the end you’re so engrossed in the character drama, that it’s really kind of an afterthought.”

Filmmaker Magazine's Erik Luers also interviewed Machoian:

Filmmaker: And in the final sequence, where a big argument and altercation takes place, I read that you were stationed in a golf cart tracking the action off-screen?Machoian: That’s right. I’ve made films in the past that explore duration, sometimes duration for the sake of duration and sometimes duration due to the scene being interesting enough to force the viewer to stay in the scene and watch the arc and feel a bit trapped. While I wanted most of the scenes in The Killing of Two Lovers to primarily be two-to-three-minute one-takes, I wanted the final argument to be one long take (I can’t remember anymore if it’s seven or nine minutes). It didn’t feel right to remain static (as we had throughout the film) for that sequence. We had used a golf cart in the opening sequence of the film (where David is running from house to house), but it wound up blowing a tire while we were shooting due to how cold it was outside. We had to get the tire fixed and that took some time.

Once the tire was fixed, we used the golf cart again to shoot the final fight scene, something we shot about two days before production concluded. We didn’t have the golf cart available for any other period of time until we were able to get the tire fixed. Once it was and we knew we wanted to use it for the final fight, I told Oscar, “Look, the best way for us to do this is for you to run the camera and be framing the scene constantly”—we obviously discussed the type of framing, etc.— and “I’m going to be the one driving you on the golf cart.” I drove the golf cart, moving forward slightly depending on how the arc of the drama was unfolding between the actors, i.e. as David begins to feel isolated, I push in farther so that we could, in many ways, isolate the viewer, too, or, as David and Nikki have that brief moment together (the “calm before storm”) where he’s struggling and she realizes he’s struggling and she loves him and feels sorry for the fact that he’s struggling, and then BAM! Then the camera begins to pull back again.

It was very difficult to get right, not the least because the wheel we had gotten fixed was now constantly squeaking! And since the tension present in the scene was so high, the squeaking wheel threatened to be a real distraction for the actors. I had to be like, “I’m so sorry, this will squeak, but we need to do it this way. We can’t walk it and we can’t all of a sudden switch to handheld.” We didn’t have access to a dolly, and so I pleaded with my actors, “I need you to go with me on this,” and luckily they trusted me. When they came to watch the dailies that night, they were like, “This is amazing,” and I thanked them. For emotional purposes, we needed to have the camera establish some distance. We’d used wides and closeups for the majority of the movie, but this was the place where we needed to move in and out of those wides and closeups.

If you’re among the legion of readers who breathlessly turned the pages of Finn’s novel, you know what’s on deck. If you haven’t, you might wonder whether you’re about to venture in a gaslighting parable, a Vertigo-style setup, another tale of a woman on the verge of a nervous breakdown or something far more sinister. To get into any plot details past this point is to play hopscotch in a minefield. What can be said is that Anthony Mackie and Brian Tyree Henry also show up, and like Oldman and Leigh, they too feel underused here; the film’s tweaked view of motherhood is a rich vein that’s never quite tapped; and you will need to endure an Overlook Hotel-level maze of plot twists and the kind of major suspension of disbelief that can leave permanent palm marks on your face.You may also want to preemptively take some Dramamine, given director Joe Wright’s penchant for throwing in skewed, Dutch-angled shots to break up the monotony every few minutes. The filmmaker has always had a gift for cracking open literary texts and getting intriguing films out of them, finding a one-size-fits-all method of turning words on a page into sound and vision; even his experimental take on Anna Karenina manages to get enough Tolstoy on the screen that you recognize the book underneath the meta-theatrical flourishes. He’s also not afraid to swing for the fences when it comes to stylizing his storytelling — this is the filmmaker who, with Atonement‘s unbroken five-minute Steadicam shot of Dunkirk’s devastation, proved that there’s a gossamer-thin line between virtuosity and indulgence.

With Window, he throws in a few grand gestures: a hallucinogenic splash of red across the frame here, a snowy car wreck transposed into a living room setting there, a couple of ingenious modern variations on the ol’ split-screen composition. Mostly, however, the playbook consists of “ape Hitchcock,” followed by blank pages. (Though kudos to cinematographer Bruno Delbonnel’s ability to inject menace into every dark corner and Danny Elfman’s Herrmann-for-all-seasons score.) When in doubt, throw in an old movie homage or, better yet, an actual clip of an old movie — Rear Window, sure, but also Laura, Spellbound, the Bogart-Bacall joint Dark Passage. These are all vintage thrillers that deal with idealized females and women in peril, mutable and mistaken identities, psychological deterioration, and the effects of trauma, which pertains directly to what The Woman in the Window is digging into with its tale of unraveling. Its inability to jolt life into this crazed, harebrained narrative, or to even sustain tension for longer than a few scenes, feels like it undermines any sort of goal of being considered in that company. You go in with high expectations about what this collection of talent can do with this batshit pulp fiction. You leave feeling like you owe Brian De Palma a thousand apologies.

In The Woman in the Window, Amy Adams plays a shut-in who is also a film buff. Every night, she swirls dark red wine in a thin-stemmed glass and falls asleep beneath glowing big-screen projections of classic thrillers from the 1940s and ’50s, babbling along to dialogue she knows by heart. Early on in the film, the camera tracks around a corner and catches a glimpse of Jimmy Stewart dangling precipitously from a ledge in Rear Window, simultaneously signaling the movie’s aspirations to greatness and underlining how short it falls. When Brian De Palma paid intelligent, self-conscious homage to Alfred Hitchcock in movies like Dressed to Kill and Body Double, he was derided by critics as a rip-off artist. Who knows what those same critics would say about Joe Wright’s work here, which suggests a destitute man’s De Palma, or maybe what it would look like if De Palma had really been slumming it all those years: a potentially juicy movie sucked dry of satirical sophistication or subversive purpose.This is not to say that Wright is untalented. Take 2011’s semi-beguiling action-sci-fi hybrid Hanna, for example. The filmmaker took a standard-issue child-assassin story line—a teenage Bourne Identity—and coded it as a millennial fairy tale, complete with Cate Blanchett as a wicked-stepmother type emerging during the film’s amusement-park climax from the mouth of a gigantic, fiberglass wolf. (It is quite an image.) Wright’s refusal to just phone things in is admirable, and what makes The Woman in the Window watchable—at least for a while—is the tension between the rote-ness of the material and the striving aestheticism of Wright’s visual sensibility: all florid, Eyes Wide Shut–style backlighting, restless, prowling cinematography, and angles that play up the gorgeous, unsettling architecture of Adams’s character’s towering New York brownstone, with its intricate network of spiral staircases and vertiginously deep drop into a forbidding cement basement.

The visual gamesmanship of The Woman in the Window is relentless, and at times the baroque theatricality of the presentation works the way it’s supposed to, conveying the confusion of a woman caught between a drab, depressive reality and a hallucinatory fantasy life, unsure which is worse. But as hard as Wright works, he can’t come up with anything as strange or destabilizing as the behind-the-scenes narrative that led to his film being delayed, reshot, and shunted off to a streaming premiere via Netflix—a trajectory that was not the original plan.

The Woman in the Window is based on a best-selling, pseudonymous novel by the notorious fabulist Daniel Mallory, whose history of lies, delusions, and borderline plagiaristic writing practices was outlined in a phenomenal 2019 New Yorker profile by Ian Parker—an investigative piece that reads like a thriller. In it, Parker juxtaposed Mallory’s use of an unreliable narrator in his debut against the author’s debunked, real-life claims of his parents’ tragic deaths (research revealed that they were alive and well) and undergoing surgery for a cancerous brain tumor (which he did not have). “Dissembling seemed the easier path,” Mallory wrote in response to the article that went so far as to compare him to Patricia Highsmith’s duplicitous psychopath Tom Ripley—a character Mallory had falsely claimed to have written a dissertation on at Oxford.

Suffice it to say that a movie about a promising young novelist lying his way to the top of the publishing industry is potentially richer than yet another variation on the archetype of the middle-aged woman whose mind is playing tricks on her. Currently, Jake Gyllenhaal is slated to play Mallory in an upcoming Netflix series that promises to split the difference between Nightcrawler and Shattered Glass. (Sounds good, actually.) In the meantime, though, The Woman in the Window arrives as damaged goods, its ending reportedly rewritten by Tony Gilroy after a series of disastrous test screenings.

The scenario of a high-profile genre movie left for dead in the wake of an inter-studio merger and the onset of COVID-19 recalls the story behind The Empty Man, but there isn’t likely to be a cult around The Woman in the Window. The question instead is whether its glossy pile-up of big stars, ridiculous twists, and hand-me-down Hitchcock-isms are enough to qualify it as enjoyably kitschy middlebrow-slasher trash, or if it just falls short of so-bad-it’s-good status—if it’s just bad enough to be bad.

At this point, it’s worth asking whether Amy Adams knows the difference, or cares. The Woman in the Window completes an unofficial trilogy with Hillbilly Elegy and the HBO miniseries Sharp Objects in which the actress—whose past brilliance is undeniable—has striven almost fetishistically to give her characters rough, jagged edges. They’re the kinds of “transformational” roles that attract awards attention—or that’s the idea, anyway. (The Oscars didn’t bite on her hillbilly act.)

Here, her Anna Fox is a child psychologist on professional leave while she sorts through some undefined trauma of her own. Wright opens purposefully on a shot of his star’s puffy, bloodshot eye (shades of Janet Leigh’s posthumous close-up in Psycho, for those playing Wright’s game and keeping score). From her eyes on down, Anna is a wreck, and Adams’s performance lands somewhere between the condescending Appalachian karaoke of Hillbilly Elegy and the kamikaze charisma of her role in Sharp Objects, where she was guided by director Jean-Marc Vallee toward a surprisingly credible portrait of self-destruction. The gimmick of her character pathologically carving words into her own flesh only partially accounted for the ways the actress managed to get under our skin.

Back when Mallory was giving interviews about something other than being a serial liar, he claimed that Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl inspired him to write his own book, but The Woman in the Window doesn’t move like one of Flynn’s thrillers. It’s locked in place, like a one-act play—an exercise in nervous tension and claustrophobia. And it isn’t funny, either, another deficiency that distances it from De Palma as well as Hitchcock, with their twin signature grins. It does, however, boast that irresistibly (and derivatively) Hitchcockian hook of a crime witnessed surreptitiously at a distance by a nosy protagonist—the voyeur imperiled by her own peeping.

Tracy Letts is a vibrant playwright, but the dialogue in “The Woman in the Window” is weirdly stilted, like someone’s chintzy mainstream-movie attempt at Pinter or Mamet. Adams’ performance is by turns commanding and tremulously self-conscious. And stuff keeps happening that’s so overwrought that the film, in its way, becomes a whirlpool of contrivance. Each time Anna tries to explain her actions, either to her husband or to a sympathetic not-quite-by-the-book police detective (Brian Tyree Henry), she seems paranoid and delusional. But, of course, if everything we were seeing was all just happening in her head, that could be its own kind of cheat. So the contrivances may have to be real after all! “The Woman in the Window” would like to be a contempo “Rear Window,” but it’s so riddled with things you can’t buy that it plays like a bad Brian De Palma movie minus the camera movement.

But by hewing close to Anna’s own intense unease, “Woman in the Window” attempts something like the recent Oscar-winning “The Father,” which adapted its protagonist’s dementia. This is the kind of stuff that Brian De Palma would eat for breakfast. He, surely, would find more disturbing and lurid avenues to explore here.

What was the audition process like for the first Mission: Impossible?I met with Brian de Palma [and] read for him. I’d already done Clear and Present Danger. This was another Paramount movie, so they had an idea of what happens when I’m playing [a character from] the CIA or whatever head. Anyway, I auditioned for Brian, and then I went off to do a film in Brazil. Halfway through that film, I got a call that Brian and Tom and the rest of them wanted me to come in and [play] Kittridge for them.

Did you have any connection growing up as a fan of the original TV show?

I did indeed.

As I rewatched the film, I was reminded that you get to deliver some very memorable dialogue associated with the show, such as “Your mission, should you choose to accept it”. How did it feel for you to bring this iconic dialogue to life on the big screen?

I was very tickled. My brother and I used to watch the show, so it was fun to share that with him specifically. Just the idea that, lo and behold, in the journey that [I’m] on, you’re going to be guy that says, “Your mission, should you choose to accept it” in this Hollywood blockbuster? OK. OK, cool. That’s another flavor that I’ll enjoy.

What was it like to work with Brian De Palma?

For me, he was a visualist. One of the things he’s known for are his setpieces. Some would say [they’re] derivative, but everything’s derivative on some level. In terms of creating tension in a Hitchcockian way, he’s terrific. The break-in to the CIA is extraordinary, I think. And the lead-up to trying to find Ethan Hunt in the [apartment] building that we were in, in Prague where that was shot, was terrific. And of course the sequence in the Chunnel is extraordinary. You put Tom Cruise and Brian De Palma together, and you’re in for a good show.

Is it true that there wasn’t a finished screenplay when the film began shooting?

Kind of, yes. As a matter of fact, I went in to do the “Your mission, should you choose to accept it” prologue, I think, three times. I went up to Lucas’ ranch [Skywalker Ranch] just outside of San Francisco to [redo] voiceover for that. They were just trying to clarify some of the mission that people were confused about in some of the screenings. As a matter of fact, this one [Mission: Impossible 7] is even more fluid than the original, I remember. It’s pretty hard to imagine that on such a large-budget film, but one of the great things is that you get to go with a certain flow, depending on what’s showing up that week, to do with weather or locations or what actors are bringing. Both Tom and McQ [Mission: Impossible 7 writer/director Christopher McQuarrie] are extraordinarily adept at capturing something that seems to be more interesting than what might be on the page.

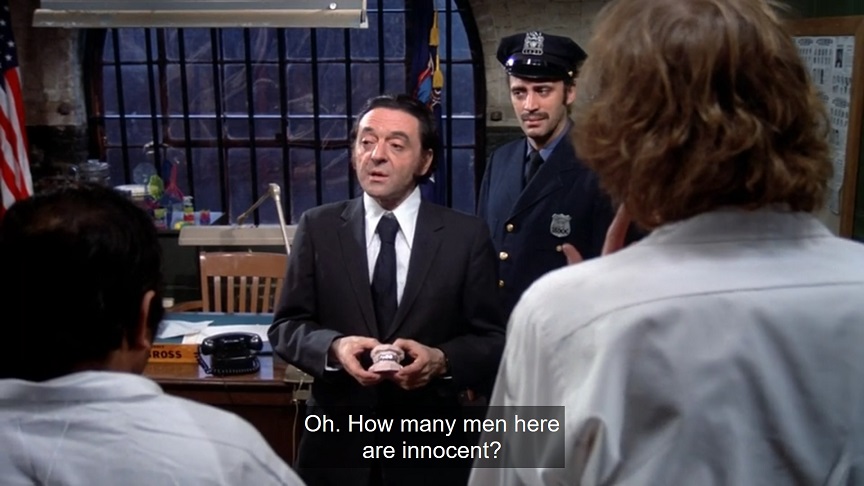

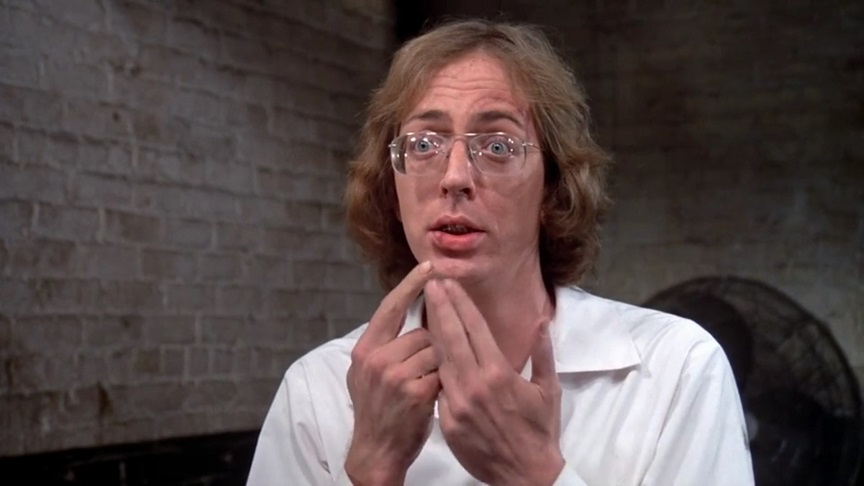

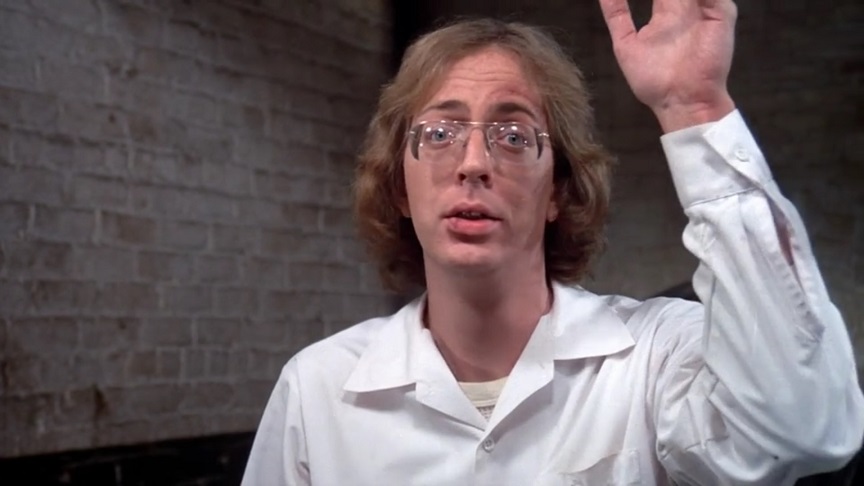

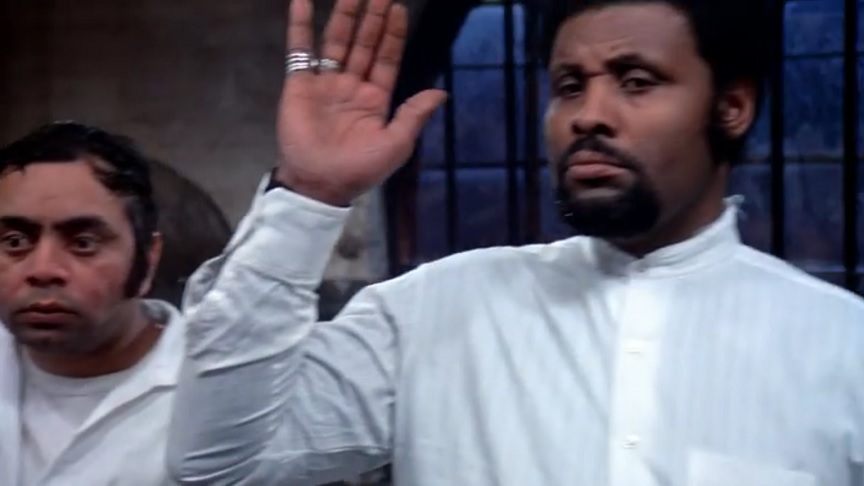

Going back to the first one, with the idea that the script might be constantly changing, do you roll with that as an actor?

No, I certainly don’t just roll with that. [laughing] I like to dig down. When action is called, I don’t want to have to be remembering my lines. I want to just forget that I even learned them and they show up in the moment. I’m not exactly Method, but I want the thing to fall out, as if you were that person. So that was a challenge. The aquarium scene, the “Red light/green light” scene – obviously, there was a lot of dialogue for Kittridge in that. The dialogue came not too far away from the day we were supposed to shoot it.

It was changing a little bit here and there. The gist of it was pretty much locked down a few days before we shot it. So I just spent a lot of time with the script, going over and over and trying to figure out where the nuances were. And why [Kittridge] was saying what he was saying, and all the sort of great stuff one normally does, just in a truncated amount of time.

What was Tom Cruise like as a scene partner?

Very focused. He was and always is. He’s profoundly focused, not just as an actor but as a producer. In anything he does, he commits to it 110% as it’s happening. You can see that in the stunts he does, in the preparation for the stunts he does. He doesn’t mess around. There is a certain playfulness about it, but when action is called, there’s no messing around. We’re gonna jump in here, as deeply as we can given the genre. So that was thrilling. It was great to act opposite that.

You mentioned the Hitchcockian tension, which comes to a head in the aquarium scene, as your character makes it clear that the opening setpiece was a mole hunt, and Ethan’s the presumed bad guy because he’s the only survivor. How did you work on achieving that tension – with dialogue coming so soon before the shoot – as the audience realizes Ethan’s on the run for the rest of the movie?

First of all, you have to lay in a belief that you have found the problem in the situation. And it’s your job to deal with that problem expeditiously and thoroughly. That’s the first thing, which is at absolute odds to what Ethan brings to the scene. Ethan’s point is, there’s a problem here. Kittridge’s point is, there’s a big problem here. And by the end of the scene, they both realize that each other is the problem. All the characters to a certain extent create heat for Ethan. Kittridge’s job is to put a fire within Ethan’s mind to solve what’s going on. He can’t use the CIA or the Impossible Mission Force to do it. He’s got to do it on his own. I had to come in with a surety, and make it clear to Ethan that his days as a mole are over.

You mentioned DePalma as a visualist in terms of your experience as an actor. I’m thinking about the canted angles he prefers, especially in this scene where the camera must have been placed at your feet looking up at your face.

Definitely. It was up the nose, [so] we made sure that there were no nose hairs that were going to keep people’s attention away from the scene.

That goes against the traditional shot/reverse shot angle for dialogue scenes. What was it like for you, knowing that you’re focused on the tension with the camera not in a normal location for the actor or the viewer?

That was weird, for sure, because one’s never been shot from that angle. But you know why he did it? To keep the aquarium in the frame at all times, to help with that tension. Ethan may be sinking in a pool; he’s a fish in a fishbowl. And of course what happens at the end is a [big] payoff. But basically, you just focus on what’s going on, what your character wants, what they’re getting back. Focus on that and let that fly.

And if there’s a problem with the delivery, or if the particular angle isn’t working or, or what you’re doing is not working given the particular angle, hopefully you have a director [who] will be able to explain it to you in a way that you can have somewhere in the back of the mind. So the next time you do it, you’re aware on some vestigial level that there’s a different approach necessary, even though the endgame is still the same.

I don’t want to play to the camera. Some people do. “You want my face? I’ll give you my face more.” And some people say, “Well, no, I wouldn’t do that.” Sometimes you’re in the midst of that usually in a television show.

While the first chunk of the film was shot in Prague, that restaurant with the aquarium was a set, right?

Yeah, it certainly was. It was in England. That was Pinewood Studios. That was not in Prague.

At the end of the explosion, it looks like you ducking over as the water is let loose – was it you or a stuntman?

Yes, that was just a big barrel of water. I think we reset the main event twice. There are bits and pieces that you pick up along the way. Once you’ve got the scene, all the essentials, then you go in and pick up what you can or what you want. If you have the time – and on these films, usually you do have the time. So, Kittridge being overwhelmed with water was basically a close-up again, of almost the same angle, camera protected, and a big bucket of water, a big barrel of water just off camera, coming down over some stuff and onto Kittridge.

What was that like? What was the feeling of having that barrel of water dumped on you twice?

Well, you’re part of the team. If you look at what Tom’s doing, and now that we have the franchise to look back on, this was just the beginning of what he was going to do over the next 25 years. His commitment and his wanting to be in the octagon, if you will, as the stuff is flying has become his trademark. That’s something he wanted to do. He doesn’t say “Yeah, I’ll be in my trailer while the stunt guy does my stuff.” No, [he] wants to do as much of it as [he] possibly can because that’s the thrill of it. There’s something about doing [stunts] in real time, as opposed to in the studio, months later with CGI and Tom is very much like that. So if he’s doing it, you know, I’m going to take a bucket of water, big deal.

As I was watching the film again, I was really struck by, as you said, this being the start of Tom Cruise doing something death-defying. I have to imagine that was pretty intense.

Yeah. And frankly, I don’t know how they got insurance to do some of the stuff. The stunts are becoming so incredibly amazing and require a great deal of precision. They prepare for months for some of the stunts he’s doing now. I’m not sure how long they prepared for [the aquarium], but certainly as he’s running out of the restaurant, there are any number of things that could not go the way they have gone in rehearsals and in preparation for the week ahead of it, and that’s Tom doing it. So there’s a lot of nail-biting when action is called and dude’s got to do the thing and run around the glass. They try and pepper it with rubber glass, but still. One slip and we’re not shooting for a few weeks. But they make sure [stunts] are as safe as they can be, but there’s always an element of risk to them. The outcome may be somewhat contrived, but the particulars within the road to the end of that outcome can be quite painful. And if not executed well, could send you to the hospital.

You spent a lot of time on the film with actor and ex-military man Dale Dye. What was it like to have him by your side, especially since your character has a kind of a love/hate relationship with Barnes?

Well, these are the colors that you bring to the rainbow of Mission: Impossible. You know, Kittridge gets bested by Ethan. So Kittridge tries to best somebody else. You know, generally in life, you’ve got a manager who’s being barked at by the CEO, and then he or she comes in and starts barking at the people under her or him to get rid of that feeling. I mean, Dale was terrific. I loved having him around because here’s the guy that – you know, do we have guns in the scene? Yes. How do we hold them? You know, we went through training to a certain extent, but to have somebody who’s been through it, on this fantastical ride – this is not the way the CIA operates generally, of course – but to have someone who’s been in the real field to just tweak it here and there within the genre that we’re shooting is invaluable. Yeah. It was lovely.

There’s so much dry humor to how you bring the dialogue to life. In terms of the direction, was there a sense of how the character’s personality would come to life? Or was that a choice that you made?

I think that’s a choice I made [laughing] because of my sense of humor to a certain extent, which can be overwhelming sometimes for other people, never for me. But also because I try not to deliver people who relish being bad guys. I think everybody wakes up in the morning thinking they’re not going to do that today, or if they are, there’s going to be something they love about what they’re doing. And the people who are the other end of the stick deserve it on some level. But the genre demands that we have good and bad to a certain extent. But one tries to flesh it out, as much as you can without tipping the genre. So, humor, if I can, will go in there.

I know that this iteration [Mission: Impossible 7] has perhaps more depth, but at the same time, a little more humor in it. Simon Pegg brings a beautiful color of humor to the franchise. It was lovely to see that nourished and blossom in the franchise. But…what’s the word I’m looking for? [The humor was] infused on purpose, let’s say. It was a conscious effort.

When the film opened, it was a big success. Was there any hope or expectation you had that Kittridge would find his way back in the second movie?

Yes, there was. How candid can I be here? Let’s see. Not that it’s all that important because it’s about something that’s in my imagination. I’ll give you a long story. So, [on] Clear and Present Danger, there was no time [to prepare]. When this came up, I thought, “Well, I best go to the CIA and see what the heck these guys really do if I can.” So I made appointments and I went to Langley, visited people and chatted about Clear and Present Danger.

And they basically talked me through how stuff might work. Of course, nothing classified, nowhere near it. I know it’s a fantasy project to a certain extent. This is not the way it works, but it’s kind of the way it works. So [they said] “Here are the particulars that we can share with you. We’ve got a liaison that will walk you through.” So that was great. So I put that in my pocket thinking when I come to the next iteration where I’m supposed to portray someone from that agency or the like, I’ll know more about it.

So I got the [Mission: Impossible] script, which was somewhat fluid. And I was new to Hollywood. This was my second big film. I thought, “Well, that’s my job.” And it has been my job in the past. I was in the theater for 10 years. You know, when you’re doing a new play, a workshop, you go away, you study up on who you’re playing and you bring bones to the writer. You dig them up and you bring them in. Some are used, some are, “No, thank you very much.” I tried that on Mission: Impossible, and of course it didn’t fit because it was not that kind of film. And it took me a while to figure that out. So as a young and full-of-it actor, I [thought] “Well, that’s interesting. They’re not really using all the stuff I brought them.”

We shot the film. That was all fine. That was great. Afterward I had a meeting with Paula Wagner [Mission: Impossible producer and Cruise’s former agent]. Even if I went on for 30 seconds, that would have been too long, given where I was in Hollywood at that time, about how we might really want to revisit Kittridge, given this and that. I have a feeling I just dumped a lot of dirt on top of me at that lunch.

So they moved on to Anthony Hopkins, thank heaven. And they had a different Kittridge each [film] and I think that was part of the plan. I think everybody was going to go, including Ving [Rhames]. They decided at some point to hold on to Ving’s character, as a part of the maypole, if you will, around which the rest of it dances. So I kind of burned my own bridge there. And lesson learned. Not “Don’t do your homework.” By all means, do your homework as much as you can, pack your bags, bring them, open your bags. And if anybody’s not interested in what you’ve packed, fine, just close them up and enjoy that you’ve learned a bunch of stuff. Just deliver as much as you can in the genre that you’re in.

With Mission: Impossible 7 delayed again, it’ll be 26 years for you between appearances. What was it like getting the call to return?

I got the call, by the way, 25 years to the day, practically.

Wow.

25 years almost to the day. I was in Brazil in mid-January in 1995 [when I got the first one]. And in 2020 in mid-January, I got a call from my representative saying that McQ wanted to talk about bringing Kittridge back. “What do you think?” [I said,] “Where are the clowns?” And they were serious. So I had a chat with McQ and he was very candid. “Look, I don’t know exactly, but I do know I wanted this character back. I want to dig around with Kittredge. Are you up to it?”

I thought about it for a couple of minutes and said “Let’s do it.” One of the cool things is, what has [Kittridge] been doing all these years? McQ wasn’t all that concerned about that. I was. I decided that he’d been to all the agencies on some level or other, had a good idea now of how the game is played and what his place is in this mechanism of national intelligence. I figured he’d been through all of them at this point, and he’d been schooled by Ethan 25 years ago. He’s known Ethan, he’s known he’s done these things, and he knows that Ethan is someone to go to, but he also feels that it’s not ever good to have one person controlling anything.

So that plays out a little bit. There’s a respect, but at the same time, it’s like fire. We need fire because we’ve got to cook, but you got to be careful with it. If you let fire do what it wants, you’re in trouble. The relationship that they had in the first one, Ethan schooling Kittridge on who the mole really was and catching the mole, was the springboard to 25 years of Kittridge going through different agencies so he wouldn’t be schooled again.

Dear Cinephiles,“Okay, here’s the Story. I come from the gutter. I know that. I got no education, but that’s okay. I know the street, and I’m making all the right connections. With the right woman, there’s no stopping. I could go right to the top.”

I can’t recall a film that has grown so much in stature as “Scarface” (1983). When it first opened it was received with mixed to negative reviews. SBIFF’s beloved friend Leonard Maltin wrote that it “”wallows in excess and unpleasantness for nearly three hours, and offers no new insights except that crime doesn’t pay.” It went on to become a box office hit, and to inspire other films, and it has had a lasting impact on hip hop artists. When the film was re-released in 2003, director Brian De Palma nixed Universal Studios’ attempt to replace the original soundtrack with a rap score.

I was in cinema heaven back in 1983, fresh out of high school and seeing it at the Ziegfeld movie palace on West 54th street. At the time, I was seriously puzzled by the critics’ reaction to the work. “My father took me to the movies,” says Tony to the Feds, explaining his knowledge of the English language. “I watch the guys like Humphrey Bogart, James Cagney, I learn how to speak from those guys. I like those guys.” I believe the original detractors were turned off by the fact that Tony is ruthless, unscrupulous and fearless. He doesn’t change. It’s an unrepentantly decadent and amoral world we navigate for the entire running time. There are no redeeming qualities in this thoroughly unattractive protagonist. He’s laser focused on his greed and ambition, and that’s why we root for him. It’s a bitter take on the American dream.

There is one scene that caused walkouts even before it was finished: the notorious chainsaw sequence leads you to believe that you’re seeing graphic details of dismemberment. De Palma has the camera drift past the action unto the street and then return. Things transpire out of sight, but the built up tension is there, and I can imagine it proves unbearable for some to imagine what actually happened. Throughout the film there’s a sense of inevitability in the journey of Tony. The house of cards that he’s built (in this case it’s a gaudy, opulent mansion of gilded marble stairs and questionable taste which by the way was shot in Santa Barbara at El Fueridis) will ultimately fall down. It’s gravity.

It’s vulgar, excessive, decadent entertainment. There are some extraordinary set pieces besides the aforementioned botched drug deal. The shootout at the Babylon Club and the altercations that precede it are tremendous. The location is bathed in pink neon lighting, and repetitive mirrors line up the walls recalling Orson Welles’ “Lady from Shanghai.” Two henchmen wait to pounce on a strung-out on cocaine Tony. A creepy comic with a grotesque mask – “the one and only Artemio” – dances with the crowd, and the machine guns explode. (For your information, the two assassins are shown to you earlier in the film, as they’re seated in front of Tony and Manny on the bus to Freedom Town. Nice poetic touch, since Tony himself is offered a green card to make a killing. )

The music by composer Giorgio Moroder, who has won three Academy Awards including one for scoring “Midnight Express” (1978), captures with its electronic sound Tony’s cold and unrelenting drive at 156 beats per minute. It’s one of the most memorable. The song “Push it to the Limit,” which is used to demonstrate Tony’s rise in wealth and position after he kills Frank Lopez (a fantastically sleazy Robert Loggia) and takes over as the head cocaine traffic in Miami, has been used to score dark horse characters in “South Park” and “It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia” amongst many other instances.

This is still my favorite De Palma work with his signature slow sweeping, panning and tracking shots, through precisely-choreographed long takes lasting for minutes without cutting. Study the infamous scene in the bathroom. It’s delicious. He knows how to tease. The finale that threatens to derail into kitsch is perfectly over-the-top recalling Macbeth as the forest of assassins moves in on him. In this testosterone-filled environment, the two women in Tony’s world make an indelible impression. A very young Michelle Pfeiffer – rail thin and eyes like a shark – is his trophy wife, and she’s heartless and a perfect object of desire for him. As Tony’s incestual obsession, Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio is heartbreaking as the innocent sister who goes to the dark side. And what can I say about Al Pacino as Tony that hasn’t already been said? It’s a master class in total commitment, the accent, the swaggart, the physicality, they are absorbing. It’s on the verge of the precipice but never becomes a caricature. It’s miles apart from his quiet work as Corleone.

Tony Montana : “You wanna f*%k with me? Okay. You wanna play rough? Okay. Say hello to my little friend!”

Love, Roger

A villain is a villain, and Jim Phelps is a particularly bitter and jealous one here. After quoting the Bible to Ethan Hunt, he (perhaps desperately) tries to dig it in that he purposely sent Claire to do the dirty work with Ethan. Whether Ethan is buying everything his mentor is trying to boast to him is another matter altogether. Calling it "gross" is perhaps this article's most questionable miscue.

Claire's involvement in the whole scheme is compellingly vague and mysterious, as she seems genuinely torn by competing impulses. Perhaps she's "living life at the gut level," with tragic consequences.

Aside from all that, an interesting look back at the film, I suppose. Here's an excerpt:

That’s the first 25 minutes of the tightly wound and constructed Mission: Impossible. But just as you might figure a film starring Tom Cruise – especially at this stage of his career – would really be about Tom Cruise, you might figure that a thriller directed by Brian de Palma has something up its sleeve. Just as it appears that the mission has gone off without a hitch, one by one, the members of the team are offed – by bomb, by knife, by strange sharp object descending from the top of an elevator. (Hasta lasagna, Emilio Estevez.) De Palma, the New Hollywood cohort of Coppola and Martin Scorsese (each of whom had directed Cruise a decade earlier), had long balanced his distinctive tendencies and influences, complex and often adult sensibilities, and mainstream success. So in the same vein as his being selected to direct the tense 1987 adaptation of another TV series, The Untouchables, De Palma got to try his hand at this one too, quickly making clear that the TV inspiration didn’t mean he wouldn’t make Mission: Impossible as much a De Palma film as a Cruise film.So about 25 minutes into Mission: Impossible, the team of many turns into a team of one. The task at hand – recovering a list of undercover agents’ fake and real identities before the list gets into the hands of terrorist organizations around the globe – is completely ruined…until Ethan learns that the whole mission was a mole hunt to rifle out the sole survivor. The scene in which Ethan realizes he’s been set up as the IMF mole, and must go on the run to clear his name, is a perfect balance of Cruise’s sensibilities and De Palma’s. It’s a relatively simple back-and-forth, as supercilious CIA director Eugene Kittridge (Henry Czerny) lays out what seems like a pretty airtight case against our hero. But the dialogue, growing more suspenseful, is a buildup to a watery climax, as Ethan employs a useful gadget: a stick of gum that can be used as an explosive when smushed together, here detonating an explosion in a swanky Prague restaurant with aquariums aplenty so he can make his escape.

Some of the hallmarks of Brian De Palma’s work are absent from Mission: Impossible. It’s one of the least lurid films of his career, far less sexy (either intentionally or subtextually) in its depiction of a kinda/sorta love triangle between Jim, Ethan, and Jim’s wife Claire (Beart). As much fun as the film continues to be, its handling of Claire as…well, anything really, is its greatest miscue, and one that gets grosser with time, as in a moment near the end where Jim refers to his wife as “the goods.” But that scene with Ethan and Kittridge both visually and verbally, tracks with many of the helmer’s predilections. The true setup of the film, even as it favors Cruise, is a pitch-perfect way for De Palma to pay homage once again to Alfred Hitchcock; Ethan Hunt is the wrong man at the wrong place at the wrong time, accused of crimes he didn’t commit and forced to clear his name with increasing desperation. And the way De Palma films the scene is vintage, with the camera not only closing in on both Cruise’s and Czerny’s faces, but doing so via canted angle, as if the camera was placed at their feet, not over their shoulders.

Though Mission: Impossible is the rare PG-13-rated film in the director’s career (a few of his efforts, including Mission to Mars, were rated PG), the visual elements throughout the film mark this as a true De Palma effort. There are touches like the canted angles at the aquarium restaurant, split-diopter shots, and the constant use of disguises – not just a hallmark of the show, but of films like Phantom of the Paradise and Dressed to Kill. (And nowhere else in the franchise can you find the truly odd image of Tom Cruise in disguise as an old Southern-accented U.S. Senator arguing with political gadfly John McLaughlin.) And then, of course, there’s the centerpiece sequence of Mission: Impossible, in which Ethan, Claire and their new cohorts, Luther Stickell (Ving Rhames) and Franz Krieger (Jean Reno), break into the headquarters of the CIA to retrieve the real list of agent names and aliases right underneath the agency’s collective nose. That sequence takes place, as Ethan hisses while in an air vent, in “absolute silence.”

Each Mission: Impossible film has at least one truly indelible image in which Tom Cruise either re-cements his status as a movie star or tries to reshape it ever so slightly. There’s no doubt what that image is in the first film: it’s the sight of Ethan Hunt dropping spread-eagle to the floor of a highly secured CIA vault housing the aforementioned list of agent names. By holding out his arms and legs, it’s as if Ethan (by which it’s more accurate to say Cruise himself) can stop himself from hitting the ground by sheer force of will. Tom Cruise’s career is marked by images of him in movement, from sliding across the floor of his house in his skivvies to flying a fighter jet because he feels the need for speed. But Ethan’s ability to be relaxed and desperate all at once, in such a fraught situation, may be the most unforgettable image associated with the performer.

That piece of action goes hand in hand with Ethan’s explosive escape from the aquarium restaurant in establishing an important piece of the puzzle of this series: Tom Cruise doing his own stunts. On one hand, the stunts in this film don’t seem as death-defying as that of climbing up the side of the tallest building in the world or hanging on the wing of an in-flight airplane (as we will see in later films). But those stunts only became possible after Cruise dangled from a wire and literally saved his own hide by catching a bead of his sweat in a gloved hand. The sense of the thrilling is communicated here, as it is in the other films in the series, specifically because the audience is visually informed that an extremely famous person has put himself in harm’s way for entertainment.

Meanwhile, the latest episode of The LexG Movie Podcast has LexG letting loose on a "Brian De Palma Lightning Round." LexG has very vague notions of the earliest De Palma works, so he zooms through most of those works, and he goes on mostly recollections of having seen most of these movies however long ago he's seen them (he hasn't gone back to watch anything specifically in preparation for this episode, so several times, he'll ask a bit of forgiveness if he gets some details wrong or misremembers something). As a "lightning round" discussion, it's a fun sort of ride.

Chris Martin: And let me ask you: I love that you have "Swanage" on your T-shirt. What is the significance of that?Alan Cross: Oh! This is my sister's tribute band. My sister is a... Well, I'm from Winnipeg, Manitoba, originally. Uh, that is the city on the planet that is the biggest, has the biggest fan base for the movie Phantom Of The Paradise.

Chris Martin: Right...

Alan Cross: Brian De Palma film from 1974.

Chris Martin: Okay...

Alan Cross: And my sister has even got a Phantom Of The Paradise tribute band... Swanage was the name of the mansion where Paul Williams' character, named Swan, lived as he tortured poor Winslow Leach into making a cantata for the opening of his club, called the Paradise.

Chris Martin: What an amazing answer to an innocent T-shirt question!

Alan Cross: I will get you a T-shirt.

Chris Martin: [laughing] Thanks, man.