CLICK IMAGE BELOW TO JOIN DGC ONTARIO ZOOM CLOUD MEETING, JUNE 18, 7PM EASTERN

Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | June 2020 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 |

| 28 | 29 | 30 | ||||

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

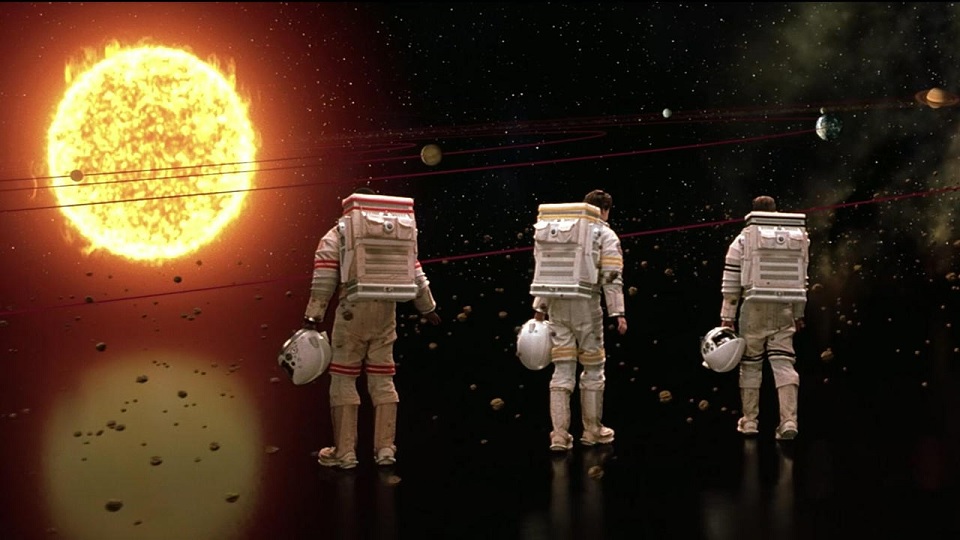

When I saw Brian De Palma’s Mission to Mars in 2000 with a heckling, pre-release audience, I didn’t think much of it. A year later, though, the American Museum of the Moving Image in Astoria screened it on a double bill with The Fury as part of a month-long De Palma retrospective, and a group of former students who took me out there to see The Fury persuaded me to stay and take a second look at Mission to Mars. Perhaps it was the juxtaposition of the two movies that made me look at Mission to Mars with new eyes, but the second time around I fell in love with it. The Fury has an almost insane narrative, but it’s a work of such visual inventiveness and emotional potency that, if you connect with it, the story is no obstacle; its excesses serve the movie just as equally ridiculous stories serve Jacobean tragedies and nineteenth-century operas. And though Mission to Mars has a much simpler silly plot, it too is a kind of outline – you might say a metaphor – for De Palma’s ideas about the tension between technology and humanity and the nature of loss, his two favorite subjects.The movie is actually about two missions to Mars, occurring a quarter-century into the millennium and a year apart. The first, involving a bicultural crew (Americans and Russians), falls to pieces when, having established themselves on the apparently unpopulated planet, they come across a structure in the crimson sand that responds to their attempts to penetrate it with an explosion that buries three of the four astronauts, sparing only Luke Graham (Don Cheadle). Earth loses contact with Luke; his comrades back home don’t know what’s happened to him or his crewmates. So they send another group up, a rescue mission, made up of Phil Ohlmyer (Jerry O’Connell), a young computer hot dog, and Luke’s three best friends, whom he trained with – a married couple, Woody Blake (Tim Robbins) and Terri Fisher (Connie Nielsen), and Jim McConnell (Gary Sinise), who would have manned the first trip with his wife if she hadn’t suddenly taken ill and wasted away from cancer. Derailed by the tragedy, Jim lost his place in the hierarchy. Now Woody and Terri persuade their boss (Armin Mueller-Stahl) to reinstate him, and he winds up in space along with them. But their vehicle crashes and Woody is an indirect casualty of the crash. The others land on Mars, where they find Luke, living alone in his space station and so haunted by ghosts that at first he assumes Jim is one, too. And they find the structure that swallowed up his crewmates. Seen from the air, it’s an exquisite sculpture of a smiling face.

The key to gaining access to the face in the sand, it turns out, is the crew’s ability to furnish proof that they’re human. Mission to Mars is a space story, but it’s the anti-2001: A Space Odyssey. In De Palma’s Blow Out, the hero (John Travolta) keeps making the mistake of putting his faith in technology; so, on a smaller scale, does the teenage boy (Keith Gordon) in Dressed to Kill who’s trying to track down his mother’s killer. For these characters, technology is at best inadequate to achieve the (human, emotional) ends they want to put it at the service of; at worst it backfires and results in the deaths of the people they care about. By the time Mission to Mars takes place, technology is inescapably the ruling force, but De Palma uses the fact of all this technology, ironically, as a way of focusing on the human dilemmas that beset the people who have to deal with its inadequacy and its capacity for bringing disaster. Science has found a way for the astronauts to float through space without the benefit of a space capsule, but only for limited amounts of time, i.e., only as long as the oxygen in the tanks strapped to their backs holds out. When Woody is unable to harness the drifting capsule after the rest of the spaceship has crashed, he finds he hasn’t enough oxygen left to return to his companions. Terri insists she should float out to rescue him – a futile act that would end up killing both of them. So Woody pulls off his helmet and meets the lethal pressure of Mars’s atmosphere head-on, an act of self-sacrifice that comes out of his love for his wife. The separation of husband and wife plays off one of the movie’s most ecstatic visual moments, when they dance together to a Motown tune in the gravity-free atmosphere of the spaceship en route to Mars. But De Palma fans will also recognize his trademark image – the character who watches in helpless anguish while someone, usually a loved one, is destroyed before his or her eyes – from The Fury, Dressed to Kill, Blow Out, Casualties of War and Mission: Impossible. Woody’s demise may be the most strangely poetic version yet of a motif that amounts to an obsession: Robbins’s face turns, magnificently, to cracked granite.

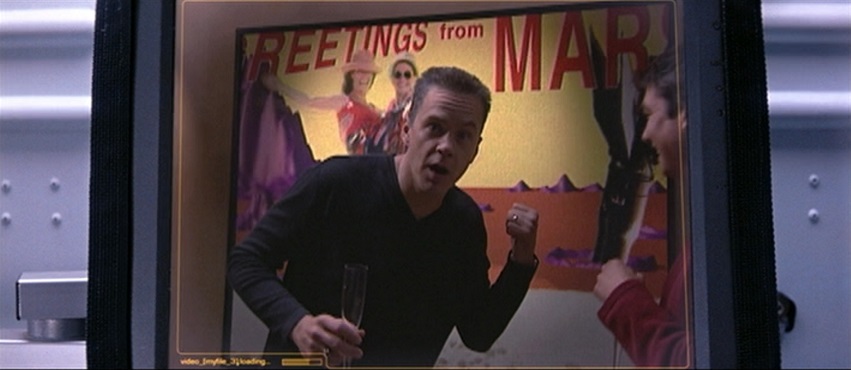

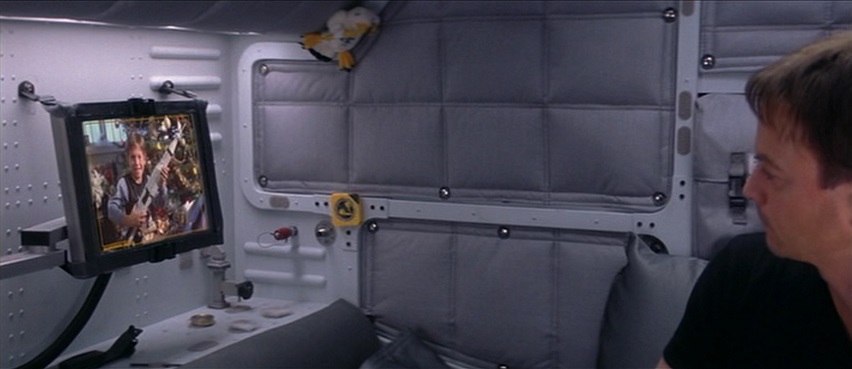

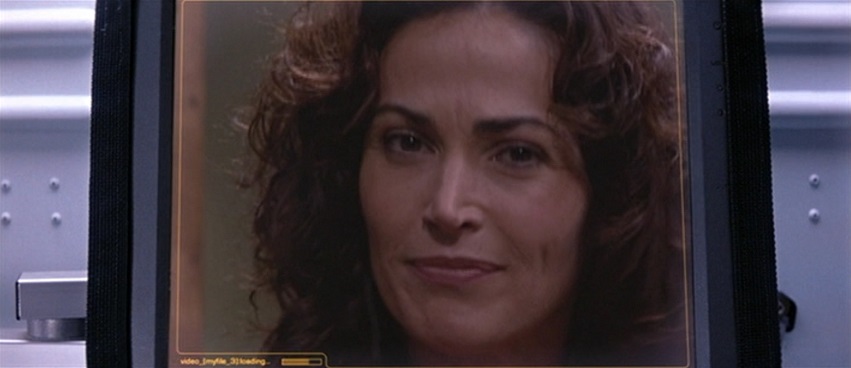

The tragedy that divides Woody and Terri echoes, of course, the loss of Jim’s wife Maggie, whom we see only once, in a video (played, touchingly, by Kim Delaney) their friends prepared when they were chosen to helm the Mars mission. Jim watches it on a monitor in the ship when he winds up traveling there without her. It’s a double-time frame sequence – the video contains images from this joyous time interspersed with earlier ones from the McConnells’ wedding. I might not have made this connection had I not just rewatched The Fury, but the visual dynamic of an image embedded within another image and two sets of observers recalls the scenes in that movie where Amy Irving is caught in a psychic link with a besieged Andrew Stevens while someone else – who can’t see what she sees – tries to communicate with her. This is a visual notion with amazing emotional resonance for these stories of loss. In The Fury, Irving’s Gillian longs to meet the boy who shares her freakish psychic gifts; her separation from him, except in these imperiled visions she has no power to alter, underscores her isolation from the rest of the world, from the people she loves who don’t share her abilities. And when she finally does get close to him, it’s too late: he’s already destroyed. The video that brings Jim’s wife back to him, if only for a few minutes, is a trick of technology that is finally just a reminder of the uncrossable distance between them. He can replay this moment of happiness and relive not only his loss but also his bafflement: here they are at the peak of their lives together, anticipating a future that, though neither knows it, will never come to pass. In the video Maggie makes a toast to them standing at the threshold of a new world, but mere months later she was sick and he stood on the threshold of life and death, watching the most important person in his life fading away from him. De Palma gets at this idea in another way, too. The transmissions the first Mars crew sends back to earth have a twenty-minute delay. Back at home, Jim and the others watch as Luke and his companions, full of good humor and optimism, light a candle in a slab of cake to honor Jim’s birthday before setting out across the sand to explore the structure. The NASA observers have no way of knowing that even while they’re watching this transmission, twenty minutes after Luke sends it, his crew is being torn apart.

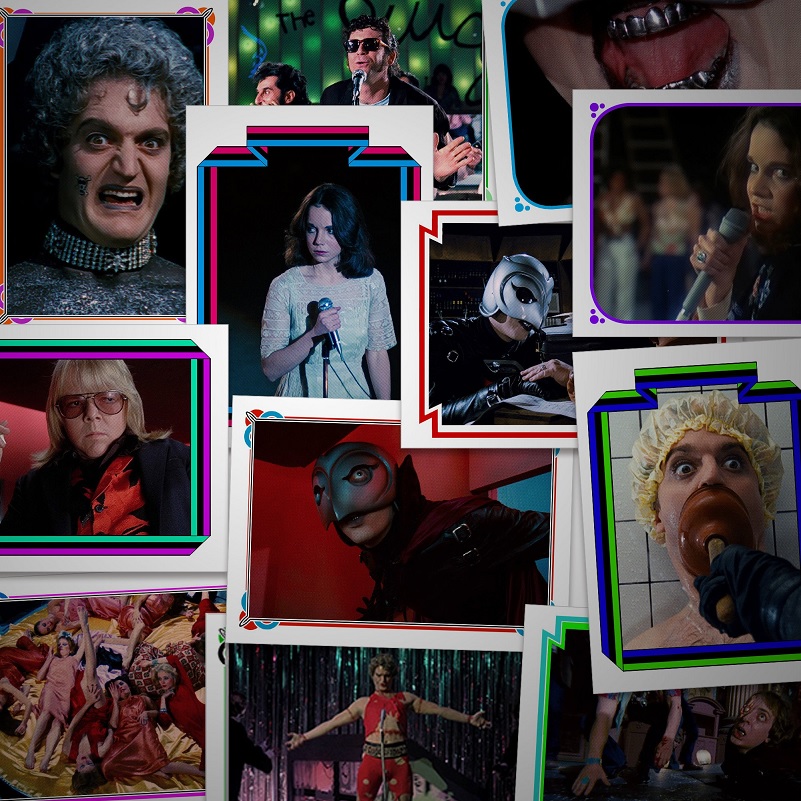

To that end, McBride also has several Phantom Of The Paradise prints available on the site, including one for the fictional "Beef Meets The Phantom Of The Park." Definitely worth checking out.

In his review, MacUistain states upfront that while Scarface "is a totally secular movie that has nothing ostensibly to do with Christianity," he will proceed to use the film to explore "the great modern American heresy" that being a good person will get you to heaven. "Bottom line up front: being likable, or 'a good person', or 'nice' is not what saves you," MacUistain explains. "You are still broken and in need of salvation outside of yourself. If you rely on yourself alone, you will perish."

Delving into the character of Tony Montana, MacUistain writes:

People are wont to admire Tony Montana’s rise to power and his “heroic” last stand. His hard work, can-do attitude, and confidence inspire a lot of people. Tony feels that he and other hard working people are getting played by the real crooks who are at the top of the pyramid. At first glance, Tony Montana is absolutely someone to admire.That is, of course, until you realize that all of his decisions led him to being shot dozens of times and floating face down in a pool of his own blood. Additionally, he has killed or driven away anyone who ever cared about him.

Tony Montana has many admirable attributes. He is incredibly smart, hard working, enterprising, charismatic, loyal, and charming. However, he uses those talents improperly, to say the least. Speaking of talents, I do believe there is a passage of scripture related to this. Why don’t you go ahead and open up the Good Book to Luke 19:11-17 and read the Parable of the Talents? How did Tony use his talents? His mother disowns him. He kills his best friend because he fell in love with his sister. He gets his sister killed after ruining her life and Tony probably suffers from some sort of malformed sexual attraction to his sister. His wife leaves him. His allies all turn on him. Every friend and employee he has is brutally killed. Yes, you went mighty wrong there Tony!

Despite all of his talents, he is not moral. He is not virtuous. “What? Sealgair you hack! You don’t think the attributes of hard work, loyalty, charisma, and devotion are moral? You’re a fraud! I’m going to write about you in the comments about how wrong and stupid you are!”

Comment away, my hypothetical friend! Let me also point out to you that those traits, admirable though they may be, do not equate to morality nor virtue. Hitler was hard working and devoted. Ted Bundy was charismatic. Mike “The Situation” Sorrentino had a damn sixteen pack, admirable as that is. None of that makes those fellows virtuous or moral. None of those traits mean anything if they are not used for an objective good. You are either on the wide path to destruction, floating around caring only about yourself, or you are on the narrow path oriented to Christ. Tony, obviously, is a selfish and loathsome irredeemable person on the wide path toward destruction.

Scarface is a morality tale. It is a cautionary tale. It is very plain and simple. Do not be like Tony.

But wait! Tony has a code! He refuses to kill children! And that is what really triggers his demise! Well, you are on the right track, but that is not really the whole story. Yes, it is true that Tony (correctly, and indeed morally) refuses to kill children. He was about to willingly assassinate a dude dedicating his life to stopping the plague of drugs, but he refused to go through with the assassination because children would have been caught in the cross hairs. Look, if the standard we use for “good dude” is comprised solely of “he does not kill children” then we have a lot of work to do as a society.

Here's a further excerpt from Taylor's article:

In June, 1975, Mission to Mars was first launched. It featured many of the same animatronics and even some of the same footage in the pre-show and ride film, but new elements were made to the show itself, both in terms of effects (inflatable seats would be inflated or deflated, to simulate space travel) and story points (hello, hyperspace travel). In 1975 Mission to Mars was installed in Disneyland too. But by the early 1990s, it was starting to show its age. It lacked the visceral thrills and excitement that modern audiences demanded and much of the science and technology was outdated and creaky. It closed in 1992 in Disneyland and 1993 in Walt Disney World. The mission had come to an end.Or had it?

Since the late 2000s, Disney had been noodling with the idea of turning some of its beloved theme park attractions into equally beloved big screen events. The test pilot was Tower of Terror, a 1997 horror comedy starring Steve Guttenberg and Kirsten Dunst that aired on Wonderful World of Disney and, more crucially, acted as an 89-minute commercial for The Twilight Zone: Tower of Terror, an innovative attraction that opened at what was then known as Disney-MGM Studios a few years earlier. (Part of the movie was actually filmed at the attraction in Florida. At the time MGM-Studios took pride in the fact that it was a fully operational production studio, even though hardly anything was ever shot there.) The movie was enough of a hit that several other projects inched through development, among them were big screen adaptations of Pirates of the Caribbean and The Haunted Mansion, along with Dinosaur, an animated film that was using state-of-the-art technology and was being developed alongside an attraction set to open at Disney’s Animal Kingdom. Ah, synergy.

But the film that would ultimately make it out of the gate first was Mission to Mars. Part of this had to do with an arms race Disney was having with Warner Bros, who was developing their own Mars-themed project called Red Planet. (A couple of years earlier Disney had found itself in a similar situation as its own Armageddon squared off against Paramount and DreamWorks’ Deep Impact.) And part of it had to do with the fact that the studio really didn’t publicize that it was based on the theme park attraction, which at the time had been shuttered for the better part of a decade. The movies-based-on-theme-park-attractions idea appealed to Disney chief Michael Eisner but it still made him nervous. It was Eisner who made the last-minute decision to add the cumbersome subtitle to Pirates of the Caribbean in an effort to distance itself from the attraction. If Mission to Mars was a success, so be it. But the connections between the theme park attraction and the movie were not going to be explicitly drawn.

And, truth be told, the movie, directed by Brian De Palma from a screenplay officially credited to Jim and John Thomas and Graham Yost, doesn’t have a whole lot to do with the original attraction. Sure, it’s about an expedition to Mars. But there aren’t any direct parallels to be drawn, save from that amazing long shot, set to Van Halen’s “Dance the Night Away,” which features a rotating circular centrifuge, that explicitly recalls a similar image on one of the screens in the Mission to Mars preshow. (It’s a deep cut, I know.) Where there could have been references, there are emphatically not. You’d think that some of the characters could have had the last name “Morrow” or “Johnson,” references to the audio-animatronic figure that gave you the rundown in the ride’s pre-show. But, alas, there is none. De Palma, whose experience on the film wasn’t particularly positive (“It was relentless,” he said in the De Palma documentary), never mentioned the original attraction. It’s unclear if he even knew the film was an adaptation of a popular theme park attraction.

When Mission to Mars came out in the spring of 2000 (happy 20th!), it lost money, making $111 million internationally from a budget of over $100 million. De Palma was so broken by the project that he left the United States. “The Hollywood system we work in does nothing but destroy you,” De Palma said in the documentary. “When I finished that movie, that’s when I got on a plane and went to Paris. Mission to Mars was the last movie I made in the United States.” (Mission to Mars did get some strong notices from critics, particularly overseas. It was #4 on Cashiers du Cinema’s collective Top 10 that year, outranking The Virgin Suicides and In the Mood For Love.) But box office be damned, Mission to Mars was going to live on.

EPCOT had wanted a space pavilion since the early 1990s. It made sense. EPCOT (formerly EPCOT Center) was the science and discovery park. Space should have always been there. Initial plans called for a giant pavilion wherein several attractions would be accessible (one would have simulated a spacewalk, with guests suspended from an overhead track, peering into the outside of a space station) but budget cuts and the popularity of Horizons, a sort-of space-themed attraction about futuristic communities, occupying the same land that the new pavilion would have been placed, meant the space pavilion was off the table. But the idea was being revisited at the close of the decade; Horizons had lost its corporate sponsorship and a large sinkhole had been detected underneath its massive show building. They could finally do the really-for-real space pavilion and they had a cutting-edge idea to go along with it: spinning centrifuge that would make you feel weightless. They also had a flashy Disney movie they could piggyback on: Mission to Mars.

Disney enlisted Gary Sinise, one of the stars of Mission to Mars, to host the preshow for the new attraction, now called Mission: Space. (Sinise essentially is playing the same character but his name is never spoken.) And the big, wheel-shaped room from the “Dance the Night Away” scene is actually a part of the attraction’s extended queue, along with several model spaceships from the film (much of the visual effects work for the movie was provided by Dream Quest Images, Disney’s in-house visual effects company, that was shuttered following Mission to Mars’ release). On a narrative level, this new attraction borrowed heavily from the Mission to Mars attraction, including the conceit that you are being trained to make the journey to outer space and the patina of pseudo-scientific education. But this time the emphasis was on thrills.

So Mission to Mars, a movie inspired by a Disney theme park attraction, inspired another Disney theme park attraction. Moving in a circle, just like the astronauts in the movie. Who has the Van Halen?

About midway through the discussion, host Scott Wampler talks about how his wife watched the film recently. "She was saying that, as much as she enjoys the movie, and feels that it's successful, she was saying she kind of wishes that a woman had written it. And... do you have any feelings on that? Does it make a difference to you if it's... if it resonates, does it matter?"

To this, Kusama responds, "I think when it resonates, it's a window into all of our capacity to have empathy, to think from another point of view. And to me, the great victory of the movie is that it is such a female point of view. Like, I don't believe that I'm looking at an interpretation of a young woman's inner life from a perspective that isn't female. And so, for me, you know, look: when [De Palma's] camera is glorious slo-mo, just tracking through a locker room and we're watching a bunch of naked girls, of course I'm aware that they're naked, but I'm also aware that they're like... I'm aware of the swagger, and the power in their nakedness. And the power in their femaleness together that to me feels akin to a locker room filled with boys. Like, I guess to me, the movie has the complexity of... I just want to say, these hopeful currents that run through it that are actually giving us access to female experience. So for me, I guess I see it as like a kind of thrilling openness on the part of the writer and director to put themselves in the psyche of this tortured girl. And I guess that, to me, says that this is where gender questions and our sort of hope for more representation gets a little murky. Because to me, this is actually a great representation of a female character as imagined by a male writer and a male director."

At this point, Wampler is so delightfully stunned by Kusama's answer that he tells her so. After a bit of laughter, Kusama continues: "Look, I'm always hoping to see... you know, some of my favorite movies have to be movies directed... most of them end up being movies directed by men. Because that's simply the... that's what was available and has been available for so long. And so if I'm going to see a touch point of deep empathy, almost uncanny willingness to go into the heart of the female consciousness, I just have to take my hat off and say, I respect that effort when it's successful. I have a lot to say when it's not successful. And don't get me wrong, I think it's just so easy for us to misunderstand and misrepresent people. That's just part of the trial of storytelling. And so, to just have... I mean, I don't know, personally, the movie has such a sort of florid sensuousness that to me it's like the female in De Palma directed that movie."

As the conversation moves on, there is talk about the shifting of tone within De Palma's film, and how one of the hosts hadn't seen it for 20 years, and didn't realize until he recently watched it again for this episode how much of a De Palma film it is. There is talk about how iconic the prom scene is with Carrie in split-screen, drenched in blood and her wide eyes, and how these are the images most people think of when they think about Carrie. "It's really incredible to me, and it shows how great a director De Palma is," co-host Eric Vespe says, "is being able to handle that tone shift, from that goofy, bouncy, lets-go-shopping-for-tuxes scene, and moving directly from that into one of the most skin-crawling moments."

Wampler then asks Kusama if that is the first sequence she thinks of when she thinks of the film. "It's funny," Kusama replies, "I actually think more about Piper Laurie in her scenes with Carrie, only because that performance was so specifically... the engine of it is sexual repression that is so intense that it just oozes out of every pore of her body.

"But, I mean, I do think that that prom sequence is iconic in so many ways. And it is true that there's a kind of technical willingness from De Palma to be just sort of firing on all cyclinders, trying a bunch of things. Really, quite literally kind of wanting to be awe-inspiring, you know. And that's the quality of, like, Medusa walking through the school gym. There are moments-- there are cuts in that scene that are so, so powerful. You know, even the idea that we haven't really seen Carrie full-body until we cut to that first moment that she starts walking off the stage and just through the mayhem that she's created. So, it just gives you shivers, you know, and that, I think... my memory of Carrie was always about that mom relationship, and what does it mean to feel like maybe your parent doesn't want you, on a most fundamental level, but also might actually kill you. [Laughs] I think that that kind of terror is so profound that it then gives... it's sort of the emotional underpinning to, then, this sort of incredible technical achievement that De Palma has with that final sequence in the prom.

And I just want to go back and say that, like... when you were talking about the De Palma-ness of the movie... I reread... I remember reading, when I was on a huge Pauline Kael kick where I was just reading every review she had ever written. I remembered her review of Carrie being kind of rhapsodic, and I went back to it to read it again last night, and was so struck by how she had nailed, not just what De Palma was doing, but also what kind of pleasure it brings. Because she said, you know, there's scary and scary, and funny and funny. But scary and funny might be the most potent combination in cinema. And that is Carrie. You know, that you can both laugh, in this kind of horrible way. And even sometimes just sort of laugh at the floridness of the filmmaking. It's like De Palma gives you permission to say, like, whoa, dude, that's a little over the top, you know. And then he just, in giving you that permission, he just goes for the jugular. And I just think there's something about that definition of De Palma's sensibility that is actually like a really important reminder of what it was that he was doing, which were these incredible experiments in tone. So he was willing to have Piper Laurie's character kind of be ridiculous when she goes to see Sue Snell's mother. But then the minute Sue Snell's mom says, "Here's five dollars. No, here's ten dollars," and you see Piper Laurie crawl back into herself... you're just like, this is gonna be such a scary movie. [laughter] So I do think there's something, too, just about the De Palma signature blend of asking the audience to kind of be in on the joke with him, and then just sort of pulling it all out from under us. That's De Palma at his best, in my opinion."

There's a lot of great discussion beyond this in the podcast, which I highly recommend listening to.

Previously:

Karyn Kusama & Diablo Cody cite Carrie & Heathers among inspirations for Jennifer's Body

Think of Brian De Palma’s first novel — Are Snakes Necessary? — as his COVID-19 movie. Produced under duress, during a period when De Palma was blocked from green-lighted big-budget Hollywood filmmaking, rather like shelter-in-place restrictions, it is as full of movie references as any De Palma film.Are Snakes Necessary? is also politically charged, continuing the obsession with skullduggery and government suspicion that goes back to De Palma’s earliest films, the anti-draft satire Greetings, and the radical activist/media satire Hi, Mom! This time. modernist De Palma satirizes the very form he essays — the hard-boiled crime novel with its built-in plot twists and duplicitous femme fatales.

Lead character Elizabeth de Carlo follows such puckish De Palma heroines as Grace and Danielle in Sisters and Laure/Lilly in Femme Fatale, where identity folds, multiplies, contrasts, and mirrors. Elizabeth and a mother-daughter duo, Jenny and Fanny, are involved with untrustworthy males: a photographer, a politician, and his political consultant, who variously exploit the women sexually and politically. Elizabeth, de Palma writes, has “innate grace.” She goes by the rule that “knowing how to speak to the animal in the man is half the game.” (She’s like Rebecca De Mornay in Alex Cox’s The Winner, a sign of De Palma’s instinctive cinematic good taste).

Tension and humor, De Palma’s two best tricks, propel the narrative, which deliberately references specific Kennedy and Clinton scandals (although De Palma indulges typical liberal petulance when labeling the offenders “Republicans”). But the villain of the piece, with his gruesome comeuppance, reveals the true political intent of Are Snakes Necessary? It is an apologia for De Palma the (supposedly) sexist pop artist.

This would be unnecessary in a fairer, more erudite era that was not held hostage to #MeToo coercion but, instead, appreciated that De Palma created more memorable and sympathetic female characters in Sisters, Phantom of the Paradise, Carrie, Dressed to Kill, Blow Out, and Femme Fatale than any female filmmaker. The sops to feminism in Are Snakes Necessary? might be the result of De Palma’s collaborating with his wife, Susan Lehman, a former New York Times editor.

In De Palma’s own field, where his virtuosity has no contemporary parallel, it isn’t likely that he would share the role of auteur with another byline. Lehman, credited as co-author, may be providing cover for De Palma’s usual misunderstood, bad-boy fantasies: “He never thought he could have everything — brains and beauty and sexy and sweet and light and hot — in one package.” Yet the novel’s strict adherence to female empowerment (“the one and only rescuer in Elizabeth’s story has been Elizabeth”) and revenge renders the novel trite. Its stock plotting lacks the larger, cosmic fate that ultimately made Carrie, Dressed to Kill, and Casualties of War so powerful and that lifted The Fury, Blow Out, and Femme Fatale into awe-inspiring, cosmic visions.

De Palma’s decision to write a novel supports his brave, hold-out position as a cinéaste who resists television. Before television conquered cinema, especially for the “golden age of cable-TV” generation and today’s streaming culture, there was a concept called “la caméra-stylo” (camera-pen), formulated by critic and filmmaker Alexandre Astruc to describe filmmaking that was as fluent and expressive as writing. The museum cruising scene of Dressed to Kill fits Astruc’s theory, as does the carefully built final sunlit tableau of Femme Fatale: pure cinema.

Although De Palma finds no literary equivalent to his famous split-screen device in Sisters or even the binocular sequence in Richard Quine’s Pushover that influenced De Palma’s voyeur fetish (which culminated in the noir extravagance of the nighttime sound-recording sequence in Blow Out), he tries writing such effects. Most of it is narrative wind-up. It takes a while before we get to the first movie moment of visual contradiction: “Rogers can’t see the paper, which if he could would stop his heart (not to mention his campaign): in clear bold print, the paper says Paternity Test Results: POSITIVE.” It’s a naughty joke, like Angie Dickinson discovering the venereal-disease health notice in Dressed to Kill combined with Obsession’s incest revelation.

Some moments show De Palma’s media sophistication (“videotaping has the potential to change how we campaign”) and his yearning to make cinema (“I need to feel the rush and shoot it”), especially his reference to The Great Gatsby’s Doctor T. J. Eckleburg, whose bespectacled eyes, on an old, faded billboard, stare down at Gatsby — an ideal De Palma image. He is a Hitchcock buff here: “Nick, crushed by the ending he has orchestrated, drops his camera to his side and looks over the railing” like Jimmy Stewart in Vertigo. He pays secret homage to Fritz Lang’s Beyond a Reasonable Doubt. And he is his own best critic here: “It all happened in that funny slow-motion way events unfold in the heat of certain moments.”

There’s also some plain good writing:

Rogers has the same general regard for applause. He treats it the way porpoises regard the shiny red balls they balance on their noses, He chases it. He relishes it. He plays it for all it’s worth. Applause is his favorite toy.Best of all are the last 15 chapters, mostly short, one-page action-filled accounts that evoke De Palma’s suspenseful, contrapuntal crosscut editing style.

In March of 2019, in an on-stage chat at the Quais du Polar in Lyon, France, De Palma had mentioned Thérèse Raquin as both a film idea he's had for years, and also as the subject of their next novel. With Lehman on stage with him, the subject came up during the Q&A when an audience member asked De Palma, "Are there any French characters, authors or films that inspire you?"

"I've made a lot of movies here," De Palma began in response. "And Thérèse Raquin is an idea I've... always had an idea for a movie for. Thérèse Raquin's been made many times, but I think I have a new way of... in fact, that's sort of the subject of our next novel, isn't it? We love the French, that's why we're here. They're very kind to me."

In fact, De Palma was close to getting his film version of this story, to be titled Magic Hour, made in 2013 with producer Saïd Ben Saïd. The pair had just made Passion together the year before. Screen Daily's Geoffrey Macnab reported that Emily Mortimer was to play the lead in the film, which was described as a "loose adaptation of Emile Zola's Therese Raquin, featuring both period and contemporary elements." Macnab added that "the story is about a film director and two actors shooting a movie version of Zola's novel and finding that it reflects experiences in their own lives."

"IT IS A KIND OF FILM TESTAMENT"

Earlier in 2013, without naming the project, Ben Saïd told Nicolas Schaller about a film he was then developing with De Palma: "This is a film about cinema that is not devoid of humor or cruelty. It happens on a shoot between a director, an actor and an actress. De Palma wrote it by drawing on things that have happened to him. It is a kind of film testament."

Previously:

De Palma's Therese Raquin film titled Magic Hour

Emily Mortimer cast in De Palma's next film