LINKS - RECENT ESSAYS FOCUS ON DE PALMA FILMS

BLOW OUT, HOME MOVIES, BLACK DAHLIA, DANCING IN THE DARK, MORE

It was "

Brian De Palma Week" last week over at the Philadelphia-based

Cinema Seventy-Six. Writing about De Palma's video for

Bruce Sprinsteen's

Dancing In The Dark (1984),

Ryan Silberstein notes how the first few shots of the video present Springsteen on stage, but without showing his face, which is revealed in the video once he begins singing. This strategy, which Silberstein links to the delayed reveal of Indiana Jones' face in

Raiders Of The Lost Ark (1981), was also utilized by De Palma three years later, for Eliot Ness in

The Untouchables. De Palma also gave

Rebecca Romijn-Stamos the same treatment (albeit with the added slap in the face) at the beginning of

Femme Fatale (2002), the opening shot of which shows a blurry reflection of her face on a TV screen.

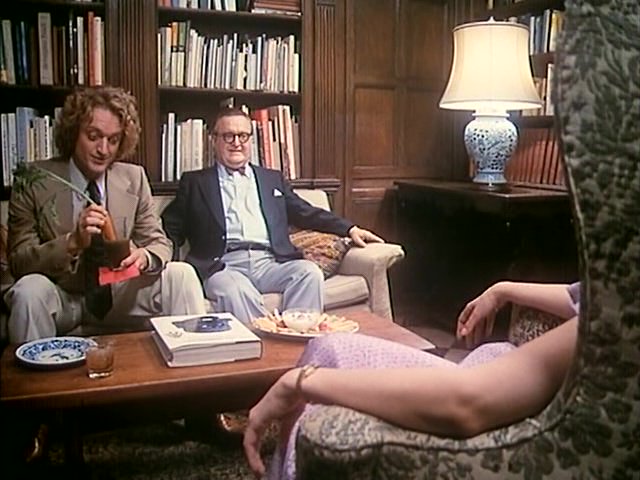

There are also earlier instances in De Palma's cinema: a similar visual strategy is used for

Nancy Allen's character (Kristina) in

Home Movies (1979, pictured here), as James brings his fiancee home to meet the family. It is not until Denis, the film's De Palma surrogate played by

Keith Gordon, sees Kristina walking toward him that we (Denis included) see her face for the first time.

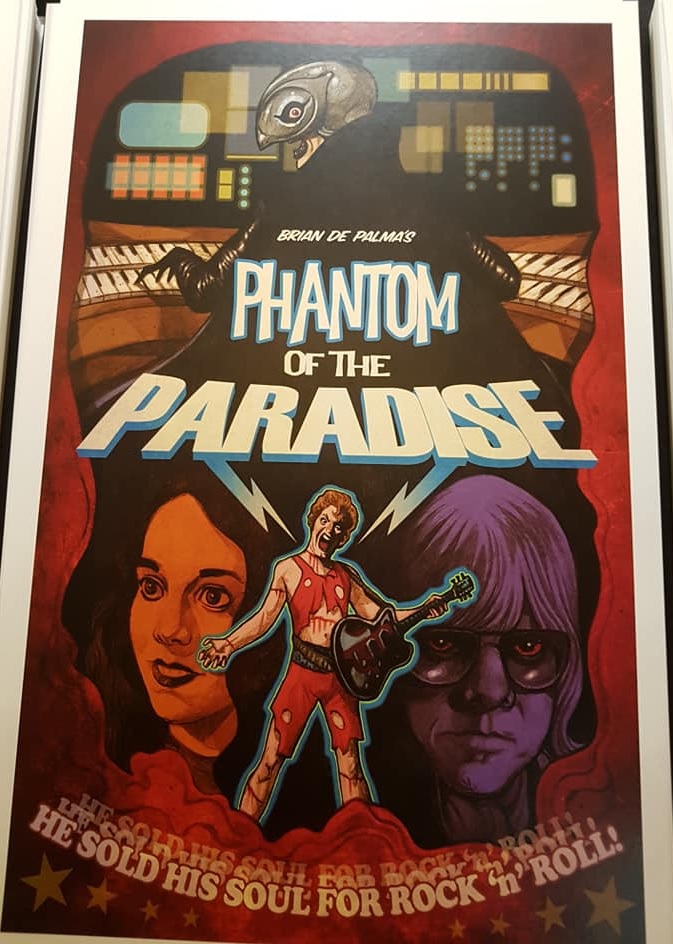

Then there is the matter of the delayed reveal of Swan's face in

Phantom Of The Paradise. When we first see Swan, it is a sort of parody of the opening scene of

Francis Ford Coppola's

The Godfather, although in this case, we do not see Swan's face until a later scene. And then there is the beginning of

Hi, Mom! -- we see everything from

Robert De Niro's (Jon's) point of view until he tells the landlord (

Charles Durning) that he'll take the apartment. (The opening of the drapes here is echoed again at the end of the opening scene of

Femme Fatale.)

Some of the films covered for Cinema Seventy-Six's De Palma week include Home Movies, The Black Dahlia, Phantom Of The Paradise, Dressed To Kill, and more. Some links and excerpts are below. But first, there was also a lengthy article about De Palma's Blow Out this week by Jimi Fletcher at VHS Revival:

The sound recording sequence is a joy – here we just luxuriate in the art of movie-making. Jack is out by the river, underneath a bridge, recording the natural sounds that he will end up using in the movie – first we hear the sound, then we follow Jack’s mic as it picks up on it, and then we see the source – a frog, a couple having a quiet talk (unlike the chat between the couple in The Conversation, this one’s absolutely harmless), an owl….and something we don’t see the source of – a strange buzzing, winding sound. What the hell is that? We soon find out that it’s Burke pulling and releasing the garrote on his wristband. One of Blow Out‘s main pleasures is giving us little clues and hints that only become truly apparent on a second viewing. It’s not the sort of thing that makes a first watch baffling, just the odd lovely touch that makes further viewings even more satisfying.

Ryan Silberstein on Dancing In The DarkBrian de Palma’s direction seems to aim at one main thing: playing into Bruce Springsteen as a sexual icon. “Dancing in the Dark” is a single from the Born in the U.S.A. album, which has the iconic butt shot of Bruce in his jeans taken by Annie Leibovitz as its cover. The album, specifically the cover more than anything else, transformed Springsteen from a socially-conscious rocker into a pop icon. The sexiness of the image is drawing directly on Springsteen’s working class background with the wear on the jeans pocked, the tucked in plain white shirt, and the dusty ball cap. This masculinity in the image taps into the same energy that Ronald Reagan was using to give Americans a renewed feeling after the “crisis of confidence” from the 1970s as stated by President Jimmy Carter. Of course, as their clash over Reagan’s use of the album’s title track on his 1984 campaign stops shows, Springsteen was aligned with the blue collar union workers of the left as opposed to Reagan’s trying to lure them rightward with a combination of promises to stimulate the economy and family values. As the song goes, you can’t start a fire without a spark, and that album cover is definitely the spark to the music video’s fire.

The video starts with a pan across Springsteen’s body from his foot up to his chest before cutting to a reverse shot. We don’t see Springsteen’s face for over 10 seconds into the video, which calls to mind the delayed introduction of Harrison Ford in Raiders of the Lost Ark. Even more striking is that it is shot entirely in closeups and medium shots for the first full minute (the runtime of the entire video is less than 4 minutes) before we get anything resembling a wide shot. This opening salvo puts Springsteen’s body front and center, his pants tight in all the right places, his short sleeves rolled up. De Palma embraces the singer’s inherent sex appeal, giving fans a better view of Springsteen on their tube televisions than they would get from most vantage points at a concert.

And Bruce is a perfect combination of sexy and goofball in this video, dancing with the microphone, smirking in between lines of the song, pointing at the audience. He’s channeling Elvis in every part of his body save his hips, since his dancing is almost entirely in his legs, arms, and shoulders. The epitome of white guy dancing. He isn’t performing at the camera, however, and only looks directly into the camera lens for a few seconds, almost accidentally. This is Springsteen in his element: it’s not about seeing crowds of people cheering him on so much as seeing the power that Springsteen has over his audience.

Gary M. Kramer on Home MoviesJames is hilarious because DePalma skewers his toxic hypermasculinity. He mistreats Kristina, his fiancé, and, in a dumb subplot, makes her resist various temptations to prove herself worthy of his love. (He’s more in love with himself than with her). In one bizarre episode, James sniffs out the junk food Kristina consumed against his wishes. Graham goes all in here, giving a wildly physical performance and he’s fantastic. He often plays James like a live-action cartoon character. Just watch his bug-eyed expressions when he gets his jaw dislocated by his father in one scene. (This also leads to him making some mastication jokes). Or a bit where he saves Kristina from choking by removing a piece of meat from her throat with his tongue. DePalma mines humor from exaggeration and absurdity, and while not all of the jokes land well—and the musical score is far too aggressive—the actors are committed. Allen, too, goes for broke, especially in a bit involving her sexual exchanges with a rabbit. Gordon is appealing in the trite role of a sensitive young man in love with his brother’s girlfriend. Unfortunately, multiple scenes of him in blackface—he’s disguised to take secret photos of his dad cheating on his mom with his nurse—are both unfunny and offensive.

Home Movies has a cheap, low-budget feel to it, but that contributes to its offbeat charm. DePalma may be in a laid-back, low-key mode here, but he still manages some stylish moments. The aforementioned choking scene, the fast food sniffing sequence, and the bit where Kristina is hit by the ambulance, have a darkly comic-horror tone to them.

Victoria Potenza on Dressed To KillWatching this film again I remembered how much I liked this film when I was younger. Around that time, I binged watch a bunch of Hitchcock films one summer and really got into thrillers so this stuck out as a staple for be growing up. I did not like horror much at the time but I loved mysteries and procedurals and it was exciting to revisit this and see all of the inspiration from Psycho. for this film. The twist is obviously similar to Psycho, but the way the film follows Kate around throughout her day and gets inside of her head feels like watching Marion Crane stealing money from her boss. The amateur detective team that tries to get evidence go undercover to dig up information is another similarity. Even the scene in the museum reminded me a little of the museum scene in Vertigo. The biggest thing I noticed while watching it this time around was how much of it reminded me of a Hitchcock/Giallo hybrid. The mysterious black-gloved killer is of course a staple of those Italian horror films, but specifically it reminded me of films like Tenabrae, Deep Red, and The New York Ripper. So many Dario Argento films featured amateur detectives similar to Peter and Liz. Deep Red features a composer, medium, and reporter trying to solve a case and Tenabrae features a writer and his assistant trying to piece together the murderers, the killer in Tenabrae also uses a razor to kill his victims. The scene when Kate is entering the elevator and the killer is on the stairwell with the bright red light on them is straight out of an Argento film and now that I love horror so much I was excited to see De Palma appreciated these films too!

Andy Elijah on Casualties Of WarAfter severely threatening him, Meserve allows Erikkson to avoid taking part in the rape by standing guard on the perimeter of their camp. But rather than looking into the jungle for any moving figures, the camera keeps its point of view on the decrepit shack that serves as the scene of the crime. We, the viewers, watch in horror as each of the other four soldiers take their turn with the young girl. As hard as it is to watch, it is handled with taste and respect. De Palma, who never shied away from eroticism before, put none of it in the sequence. It turns out not to just be the camera that is watching, but Erikkson himself. What is so rewarding about loving De Palma's filmography is seeing the auteuristic marks he always manages to insert–whether it be a studio for hire job or a passion project–and this moment of "seeing" falls right into his obsession with being a voyeur. Erikkson is made to be a witness to the crime, as is the viewer. It's as if we could be called to the stand to testify when everything is over. So many characters in De Palma films get themselves into trouble by finding something, or someone, from which they can’t look away. Where as in the past, it was perhaps a source of arousal, here, it is a horrible truth that can't be unseen.

Dan Scully on Phantom Of The ParadiseIt wasn’t until very recently that I first saw Brian De Palma’s Phantom of the Paradise. Since my first viewing at Shame Files Live, I’ve gone on to watch it multiple times, both in a theater and at home, and every time it gets exponentially better. What a strange thing indeed for a silly, metatextual rock opera to emerge from the brain of a filmmaker once touted the “master of the erotic thriller.” Yet the more I watch Phantom, the more I think it might be the quintessential De Palma film. It’s certainly the only one I know of that feels like self-commentary — which is doubly special given that De Palma himself is no stranger to strong opinions on the nature of the film business. So what is De Palma saying with Phantom? Well, before I get ahead of myself, let me share with you the one thing that has always stuck with me about his work. De Palma’s camera always seems to be hiding from the actions it’s capturing. What I mean is that my favorite filmmakers typically tend to make their camera invisible to the audience. To me, a great shot is one I don’t think about unless I’m actively analyzing it. It’s for this reason that I fucking HATE shaky cam. A smart shot is not one that announces the director’s presence, but rather one that draws the viewer into the reality of the film. Typically, this means that the performers are tasked with the thankless job of ignoring a camera that is all up in their business. De Palma takes a much different approach. His camera is certainly not present to the audience...but neither is it to the performers. Instead, it feels like surveillance. It‘s like De Palma is spying on his own movie. I can’t think of another filmmaker who does that (maaaaybe Jonathan Demme?).

This style is certainly appropriate given his own history with surveillance as an adolescent — baby De Palma rigged a camera system to catch his father in marital infidelity. In this instance, the camera HAD to be hidden.

Phantom of the Paradise, however, is the only film in De Palma’s body of work that brings the camera into the narrative explicitly by having the performers directly address it during certain sequences. It happens quite a few times, but the most striking example is during Phoenix’s audition for the Paradise. As she chicken dances her way through Special To Me, she makes direct eye contact with the camera and sings as if she’s giving a private performance to viewers of the film. It’s a striking moment that shows the audience exactly what the intended tone of the film should be. Phoenix doesn’t necessarily know she’s in a movie, but the movie itself sure as hell knows just what it is. This sets the table for the thematic questions posed throughout the duration of the film.

Matthew McCafferty on The Black DahliaAnother part of the problem with the initial reception of this film was the success of 1997’s L.A. Confidential. Both L.A. Confidential and The Black Dahlia were adapted from novels written by James Ellroy. These two novels were part of a small series of crime books that Ellroy wrote, all based in 1940s and 1950s Los Angeles. So when The Black Dahlia was coming out in 2006, expectations were high. Another Ellroy novel adaptation — and better yet — directed by Brian De Palma. It had to be great. The hype quickly turned to disappointment, which quickly turned to negative reviews. Again, I understand that The Black Dahlia will never be mistaken as one of De Palma’s best movies. But De Palma does deliver an enjoyable crime thriller once you connect the dots with the plot. And the ending itself actually wraps up pretty nicely. The actual Black Dahlia murder case was never solved, but this film is based off of the novel, which mixes in fact and fiction. So you do end up with some resolutions on motives and other aspects of the plot if you stick it out to the end.

Separating myself from the hyped-up expectations that were attached to this during its initial release in 2006 turned out to be a good thing. If you avoided this film like me over the years, put aside the negative noise from its reputation and give it shot.

Garrett Smith on Blow Out

I also really like the way Terry's life starts to become a slasher movie in some sense. His life starts to look and feel like the "trash" that he works on, and I think this is one of the most effective ways De Palma illustrates Terry's experience of being inside a conspiracy theory. Conspiracy theories are often constructs we create to help explain what we think is so unfair, it has to otherwise be impossible. While it ultimately seems like Terry's fears are well founded, his paranoia leads to what might be considered a "bleeding over" of his work into his real life. But here's where I have to be clear about why I've brought The Conversation into this... well, conversation. Blow Out is a thriller full of literal thrills. Thrilling cinematography and sound design, thrilling plot reveals and performance moments, thrilling pacing and editing. And yet, I never quite felt the deep paranoia that I believe I'm meant to recognize in Terry's experience of all of this. Whereas The Conversation, in its obsession with minutiae and methodical storytelling which can feel a bit slow, is ultimately a movie that makes me feel as insane as the main character by the end. This never quite got there for me, and I think it may be because this seems much more definitive in its conclusions than The Conversation does. While I find the idea of proving once and for all that politics are corrupt from top to bottom appealing, it seems more in line with what we know about paranoid types and conspiracy theories for someone to be left fully broken by even investigating that notion, and for us to never know which pieces, if any, were true.

That said, Terry is certainly left broken by this experience. And the end of the movie is truly chilling. Without spoiling it, I will simply say that the final moment in which we see what all of this has ultimately amounted to is so disturbingly reductive of the experience itself that it's practically a punchline. A dark, hollow joke that lines up nicely with what I just said about The Conversation. So I hope you'll take that minor criticism with the grain of salt it's meant to be garnished with.

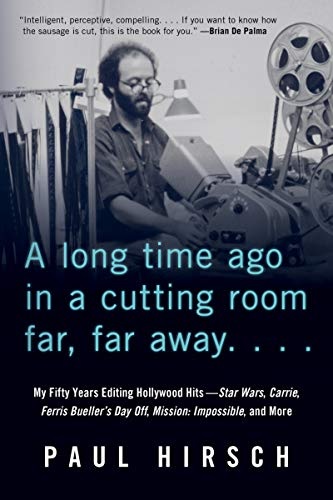

November 5th is the publication date for Paul Hirsch's book, A Long Time Ago in a Cutting Room Far, Far Away: My Fifty Years Editing Hollywood Hits―Star Wars, Carrie, Ferris Bueller's Day Off, Mission: Impossible, and More. Promoting the book, in which Hirsch writes about his experiences over 50 years in the film business, he recently spoke with

November 5th is the publication date for Paul Hirsch's book, A Long Time Ago in a Cutting Room Far, Far Away: My Fifty Years Editing Hollywood Hits―Star Wars, Carrie, Ferris Bueller's Day Off, Mission: Impossible, and More. Promoting the book, in which Hirsch writes about his experiences over 50 years in the film business, he recently spoke with

It was "Brian De Palma Week" last week over at the Philadelphia-based

It was "Brian De Palma Week" last week over at the Philadelphia-based  On November 7,

On November 7,