AND 'MARY QUEEN OF SCOTS' DIRECTOR HAD TO FIGHT TO INCLUDE "A PERIOD IN A PERIOD MOVIE"

Saoirse Ronan discusses her new film, Mary Queen of Scots, in a profile piece written by Erica Wagner at Harper's Bazaar:

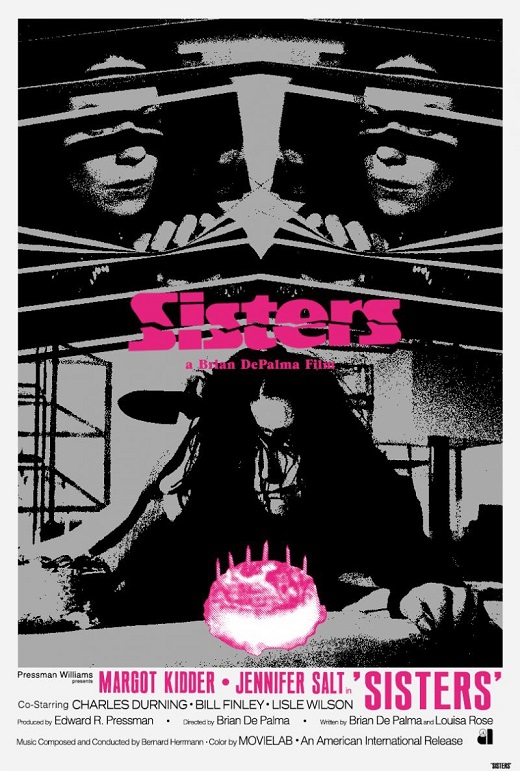

Saoirse Ronan discusses her new film, Mary Queen of Scots, in a profile piece written by Erica Wagner at Harper's Bazaar:In the film, Mary’s womanhood may not completely define her: yet one aspect is strikingly on display. We see the Scottish Queen get her period, staining her white shift; the ladies-in-waiting clean her, and the cloths they rinse swirl blood into a bowl of water. I’ve only ever recalled menstruation being referenced in Brian de Palma’s Carrie – not the most positive example, I offer. Ronan disagrees, and argues that the sense of shame that still surrounds this everyday aspect of women’s lives should be removed. ‘What’s genius about Carrie is that it shows what it feels like when you have your period for the first time,’ she says. ‘When I watched it as a teen with my mam, I’d already had my period for a few years, but if I hadn’t known what it was, I’d have thought I was dying. And that’s why it needs to be talked about.’Mary, of course, is only one of the impressive roster of powerful women Ronan has embodied in her career. Her role as Briony in the film version of Ian McEwan’s novel Atonement gained her an Oscar nomination when she was 13. Since then she has given one riveting performance after another: as Eilis in Colm Toibin’s Brooklyn; as the heroine of Lady Bird; in On Chesil Beach, another McEwan adaptation. And she made her Broadway debut in 2016 playing Abigail in Ivo van Hove’s acclaimed production of The Crucible.

‘From a purely selfish point of view, I’ve always wanted to play characters who are well-rounded and interesting and smart, or who are intelligently written,’ she says. ‘And because that’s what I’ve always wanted to get out of it, the films end up reflecting that. They’re the only roles I want to play. Even when I was a kid, I knew I didn’t just want to play “the sister”, or “the girlfriend”, or “the secretary”. That was always a priority for me, to play someone who –even if they were only in a few scenes – really had something to them.’

It’s clear she doesn’t have much time for the notion that films with women in them are ‘women’s movies’. In part, I think that’s because – blessedly – she is of a generation that’s moved past such regressive ideas, although she knows there’s still some ground to cover. ‘With Lady Bird,’ she says earnestly, ‘the amount of guys who would come up to me – and I had it with Brooklyn as well – and be like, “I’m not usually into films like that, but ah... I really liked that, and I even cried a little bit because I loved it so much”. And I’m like,“What kind of films do you mean?” Of course, they mean female-led movies. But the thing is, whether there’s a girl or a boy leading it, Lady Bird is about someone preparing to leave home. That’s it. And the more specific you can make it to one person's experience, the more universal it will be.'

Meanwhile, The Guardian's Charlotte Higgins recently posted an interview with Mary Queen of Scots director Josie Rourke, which delves into the pushback Rourke received from producers, who wanted her to cut the period scene from the film:

The film has much to say about bodies: about the queens’ different calculations about marriage and producing an heir; about the violence done to women by men; about sexual pleasure; about physical closeness between women friends; about clothing as a projection of power and desirability. When I last saw Rourke, several months previously, she had been arguing with producers over the edit. She wanted to include scenes that showed Mary having her period, and another that showed her being given oral sex.“I was fighting for a period in a period movie,” she says. “Those were instructive discussions about how honest we were being about women’s bodies and what they do, women’s pleasure and what that is, and a queen’s body as a political canvas. I felt that was something I hadn’t seen before, that I just really wanted to show. There are not many of us who know what it feels like to be a crowned head of Europe – but what we do know is what it’s like to fight for the rights of our bodies.”

She got her way in the end: the scenes are still there. “We need to show this stuff. It does need normalising. A journalist asked me how hard it was to shoot the scene where Mary has her period, and my answer was, ‘Not hard at all!’ There were six women in that room, and it was probably the thing that just most easily staged itself. But it does continue to freak some people out.”

As for the cunnilingus scene, Rourke did not employ an intimacy director – a safeguarding role increasingly being discussed in the performing arts. Rather, she worked with the choreographer Wayne McGregor, who was movement director for the film. “I don’t think I’ve ever done a sex scene without a movement director, without treating it as a piece of choreography,” she says. “I hope the sex scenes feel truthful and alive. To think in a language of movement helps remove embarrassment, discomfort or shame.”

Updated: Sunday, January 13, 2019 12:33 AM CST

Post Comment | Permalink | Share This Post

"The movie might not get many midnight showings,"

"The movie might not get many midnight showings,"

I somehow totally missed this last August, but earlier this year,

I somehow totally missed this last August, but earlier this year,