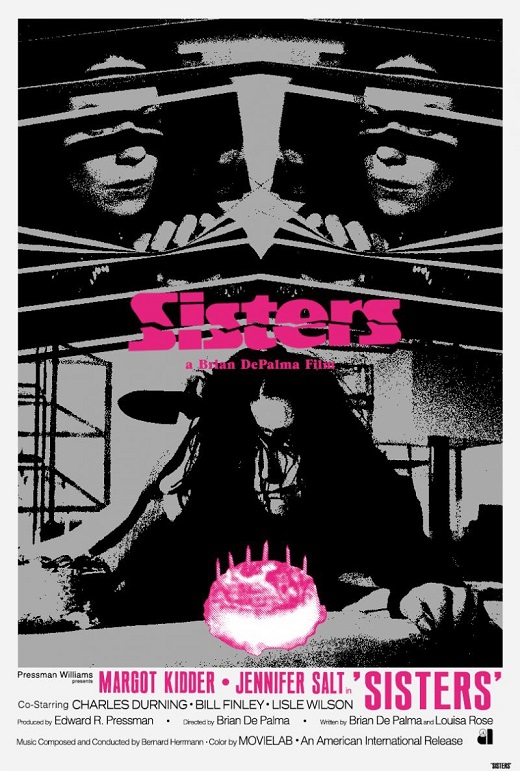

JENNA STOEBER - SISTERS "DELIVERS WEIRDNESS IN A WAY MODERN MOVIES DON'T"

"The movie might not get many midnight showings," Polygon's Jenna Stoeber stated about Brian De Palma's Sisters last month, "but it’s still a cult classic." Well, here we are just a month later, into the new year, and Sisters is in the middle of a two-screening run at The Texas Theatre, and also played tonight at The Brattle Theatre in Cambridge, MA. Last month, Stoeber's article caught the attention of Joyce Carol Oates, who tweeted the headline and link: "Brian De Palma’s Sisters delivers weirdness in a way modern movies don’t."

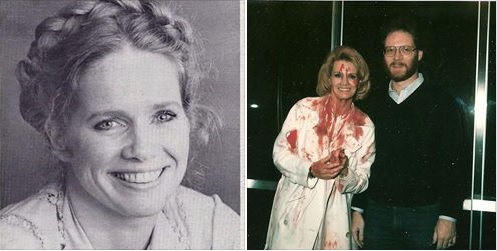

"The movie might not get many midnight showings," Polygon's Jenna Stoeber stated about Brian De Palma's Sisters last month, "but it’s still a cult classic." Well, here we are just a month later, into the new year, and Sisters is in the middle of a two-screening run at The Texas Theatre, and also played tonight at The Brattle Theatre in Cambridge, MA. Last month, Stoeber's article caught the attention of Joyce Carol Oates, who tweeted the headline and link: "Brian De Palma’s Sisters delivers weirdness in a way modern movies don’t.""Watching Sisters," Stoeber's article begins, "Brian De Palma’s 1973 psychological horror film, is like meeting your best friend’s parents for the first time and suddenly understanding something about your friend that couldn’t have known otherwise — where they came from, and how far they’ve come. A relatively early entry in De Palma’s long and storied career, Sisters features plenty of the style he would become known for, with eyes firmly on Alfred Hitchcock."

After some plot description, Stoeber continues:

Sisters features de Palma at his most Hitchcockian. It’s full of homages, with cheeky nods to the repercussions of voyeurism and the instability of sanity. It even features a piercing score by frequent Hitchcock-composer Bernard Herrmann.But more than that, the technical skill inherited from Hitchcock can be seen in de Palma’s ability to make even mundane events sinister and captivating. Before the stabbing, when Danielle and Phillip are getting frisky on the couch, we get a careful zoom-in on the wide mound of scar tissue down her hip. A low-angle tracking shot follows Phillip as he brings in a birthday cake — and a knife to cut it with. It brings to mind shots of the house looming over Bates Motel, or Norman Bates surrounded by taxidermied birds. The anticipation of violence heightens the tension long before the knife flashes.

From start to finish, Sisters is weird, but it rarely feels like it’s just for the sake of being weird. Some of the plotting might feel familiar to modern audiences; the idea that one conjoined twin is evil and the other good is borderline cliché at this point. But the story is infused with so many off-kilter details that even when you know what’s going to happen, you can never predict how you’ll get there.

In the scene in which the police investigate of the apartment, you imagine that Danielle is going to charm her way out of the situation. Collier discovers the birthday cake bearing two names, proof Danielle lied about being in the place alone and for a moment it seems like she’s going to be caught. But in her haste to present it to the police, she fumbles and drops it directly on the detective’s shoes.

It’s a shockingly funny moment, and it’s the sort of strong tonal shift that most modern thrillers or horror movies don’t dare attempt. Sisters has a lot of diversions that are almost slap-stick, and it can afford to because de Palma is so deft at creating tension. Even in this early stage in his career, he breaks the mood knowing he can rebuild it later, more than practically any other director, including his contemporary peers or Hitchcock himself.

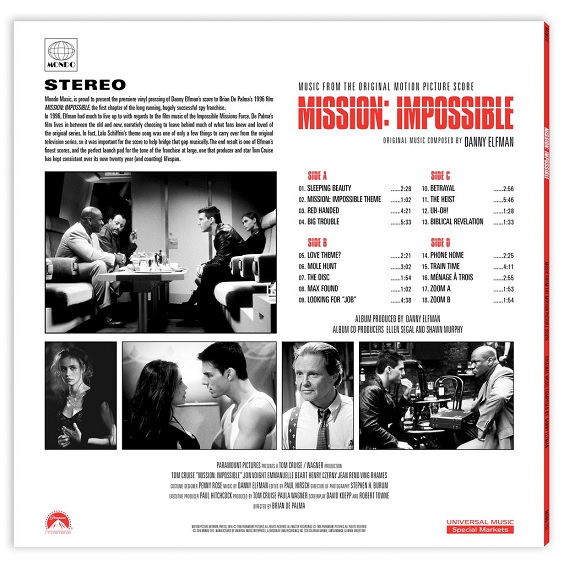

In an interview published as part of the new Criterion Collection edition, de Palma explains that he was emulating Hitchcock “in order to work out my own problems as a storyteller.” Since then, he’s directed a startling number of movies that have indelibly changed American culture, like Carrie, Scarface, The Untouchables, and Mission: Impossible. As far as exercises in self-improvement go, I’d say Sisters is a remarkable success.

I somehow totally missed this last August, but earlier this year,

I somehow totally missed this last August, but earlier this year,

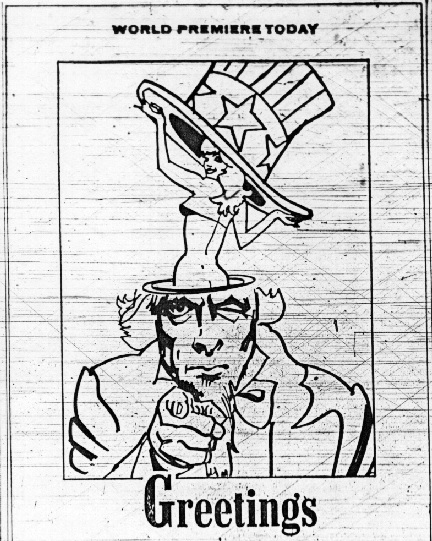

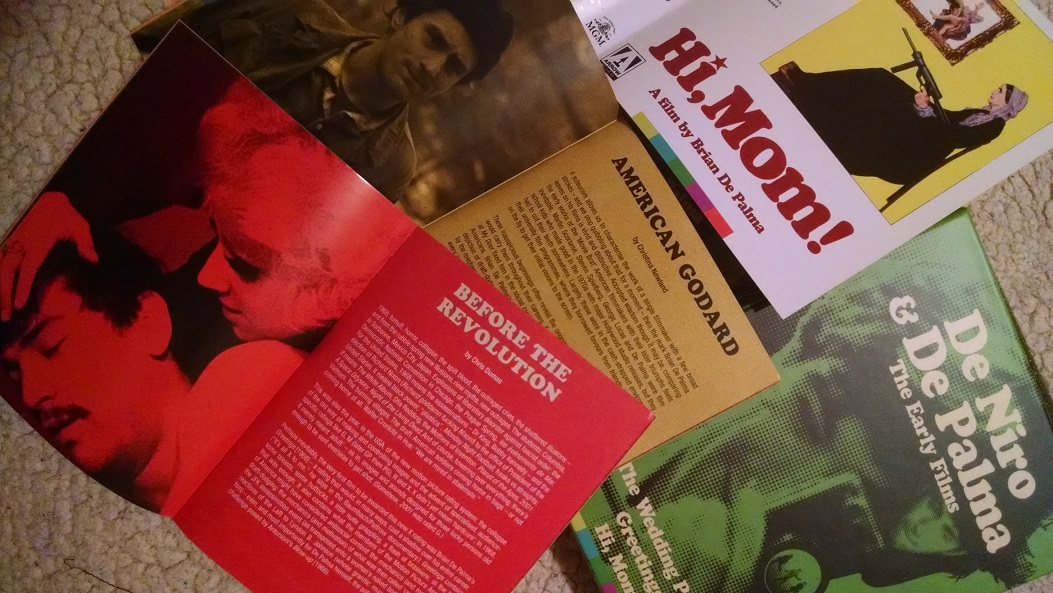

Brian De Palma and Charles Hirsch's Greetings opened at New York's 34th Street East Theater on December 15, 1968. It was the first movie to be rated X by the MPAA. As Glenn Kenny discusses during an audio commentary track included on Arrow Video's new Blu-ray of Greetings, Hirsch pitched the idea for the movie to De Palma as an American version of Jean-Luc Godard's Masculin Féminin. They began shooting on 16mm film, but quickly realized that the format would limit the potential release to very few art houses, according to Laurent Bouzereau, in his book The De Palma Cut. Bouzereau adds that the film initially made three times what it cost (the cost was about $43,100). The film was panned in the New York Times by Howard Thompson, who stated that while De Palma and Hirsch "are determined and camera-minded," they should try next time "for something that matters instead of the tired, tawdry and tattered." A few weeks later, the paper ran three letters from readers in defense of the film, under the headline, "Was That Any Way To Greet 'Greetings'?" William Bayer's letter began, "When a good film is misunderstood and then characterized by Howard Thompson of The New York Times as 'tired, tawdry, and tattered,' it is time to come to the rescue." Kenny quotes more from these letters in his audio commentary.

Brian De Palma and Charles Hirsch's Greetings opened at New York's 34th Street East Theater on December 15, 1968. It was the first movie to be rated X by the MPAA. As Glenn Kenny discusses during an audio commentary track included on Arrow Video's new Blu-ray of Greetings, Hirsch pitched the idea for the movie to De Palma as an American version of Jean-Luc Godard's Masculin Féminin. They began shooting on 16mm film, but quickly realized that the format would limit the potential release to very few art houses, according to Laurent Bouzereau, in his book The De Palma Cut. Bouzereau adds that the film initially made three times what it cost (the cost was about $43,100). The film was panned in the New York Times by Howard Thompson, who stated that while De Palma and Hirsch "are determined and camera-minded," they should try next time "for something that matters instead of the tired, tawdry and tattered." A few weeks later, the paper ran three letters from readers in defense of the film, under the headline, "Was That Any Way To Greet 'Greetings'?" William Bayer's letter began, "When a good film is misunderstood and then characterized by Howard Thompson of The New York Times as 'tired, tawdry, and tattered,' it is time to come to the rescue." Kenny quotes more from these letters in his audio commentary.

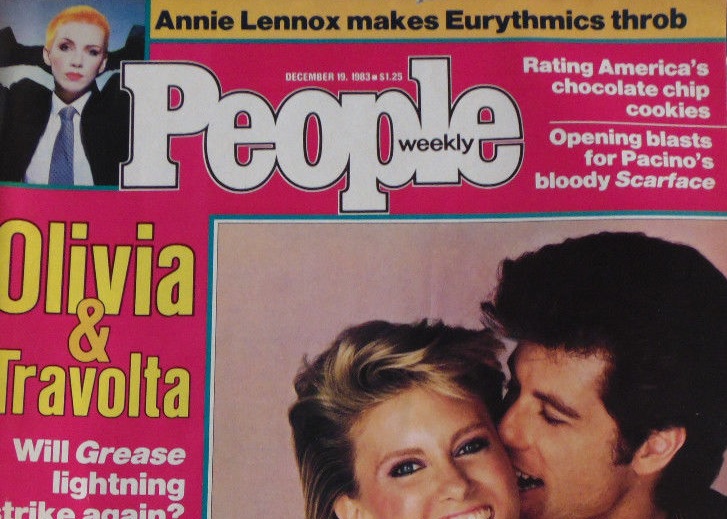

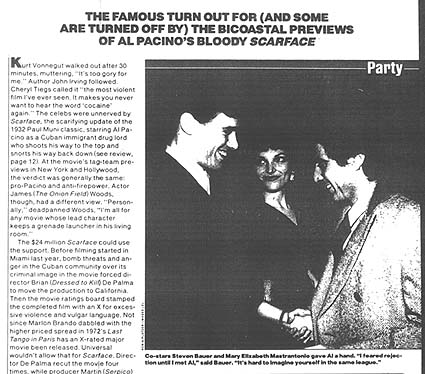

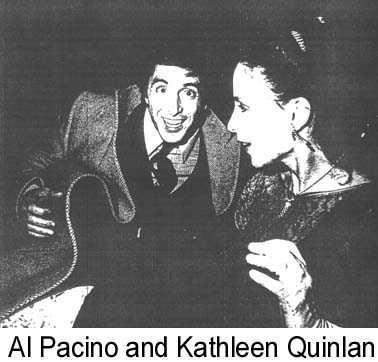

Pacino himself missed the New York preview because he was performing in a Broadway revival of David Mamet's American Buffalo, although he appears to have made it to the afterparty. In the photo to the left, Pacino is leaving the New York party by limo with his then-current girlfriend Kathleen Quinlan. In the photo at the top of this page, he is shaking hands with co-stars Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio and Steven Bauer. The caption underneath the photo quotes Bauer: "I feared rejection until I met Al. It's hard to imagine yourself in the same league."

Pacino himself missed the New York preview because he was performing in a Broadway revival of David Mamet's American Buffalo, although he appears to have made it to the afterparty. In the photo to the left, Pacino is leaving the New York party by limo with his then-current girlfriend Kathleen Quinlan. In the photo at the top of this page, he is shaking hands with co-stars Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio and Steven Bauer. The caption underneath the photo quotes Bauer: "I feared rejection until I met Al. It's hard to imagine yourself in the same league." The article says that Lucille Ball was the favorite of fans watching from the sidewalk, until Eddie Murphy arrived to upstage her. Murphy is pictured at left with Diane Lane, who arrived late herself. Murphy said, "Al Pacino is my favorite actor. I know the dialogue to all his movies. When I met him, I groveled." The article says that the preview audience was more subdued after the screening, quoting Lucille Ball (whom the article consistently refers to as simply "Lucy") as saying, "We thought the performances were excellent, but we got awful sick of that word."

The article says that Lucille Ball was the favorite of fans watching from the sidewalk, until Eddie Murphy arrived to upstage her. Murphy is pictured at left with Diane Lane, who arrived late herself. Murphy said, "Al Pacino is my favorite actor. I know the dialogue to all his movies. When I met him, I groveled." The article says that the preview audience was more subdued after the screening, quoting Lucille Ball (whom the article consistently refers to as simply "Lucy") as saying, "We thought the performances were excellent, but we got awful sick of that word." Martin Bregman hosted an after-preview party for 130 guests at Sardi's in New York, where Cher, who brought her 14-year-old daughter Chastity along, told People, "I really liked it. It was a great example of how the American dream can go to shit." Raquel Welch, who also brought along her daughter Tahnee, said, "A lot of people will enjoy the comic-strip violence that goes on ad nauseam." Welch is also quoted in a photo caption as saying that "the violence is just for effect."

Martin Bregman hosted an after-preview party for 130 guests at Sardi's in New York, where Cher, who brought her 14-year-old daughter Chastity along, told People, "I really liked it. It was a great example of how the American dream can go to shit." Raquel Welch, who also brought along her daughter Tahnee, said, "A lot of people will enjoy the comic-strip violence that goes on ad nauseam." Welch is also quoted in a photo caption as saying that "the violence is just for effect." Another mother-daughter pair of interest showed up at the Los Angeles premiere: Tippi Hedren and daughter Melanie Griffith. Griffith at the time was married to Steven Bauer, and would go on to star in Brian De Palma's very next film in 1984, Body Double. According to the September 16 2003

Another mother-daughter pair of interest showed up at the Los Angeles premiere: Tippi Hedren and daughter Melanie Griffith. Griffith at the time was married to Steven Bauer, and would go on to star in Brian De Palma's very next film in 1984, Body Double. According to the September 16 2003