BRIEF FROM ONE OF THE BOOKLETS - CHRISTINA NEWLAND ON 'HI, MOM!'

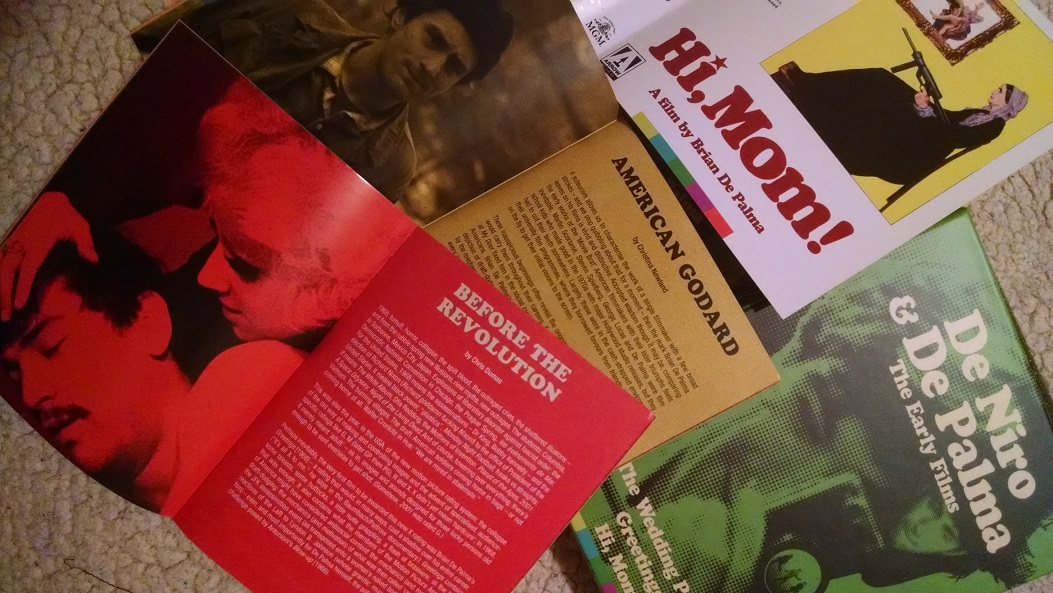

Arrow's new limited edition box set, "De Niro & De Palma - The Early Films," is here, and, having only delved partway through so far, it is nonetheless very very cool. The final product does not have two of the originally expected extras: new interviews with Gerrit Graham and Peter Maloney are nowhere to be found. What is here, however, is terrific-- even with two of the films, The Wedding Party and Greetings, sharing the same disc (original marketing imagery for the collection suggested three independent discs and covers).

Appearing in the booklet for Hi, Mom!, Christina Newland's essay, "American Godard," is named for Brian De Palma's off-the-cuff remark to an interviewer in 1969 that "If I could be the American Godard, that would be great." Linking these early films to De Palma's later work, Newland states that De Palma's style "has always cheerfully drawn attention to itself." Focusing on Hi, Mom!, Newland writes that the film's narrative "speeds along with nervy ingenuity and a chaotic structure; you might say this is a film with a multiple personality disorder. Loosely divided into three jarring acts, each more wild than the last, De Palma follows a chameleonic young man, Jon Rubin, on the streets of New York City, attempting several different utterly insane ambitions."

Toward the end of her essay, Newland zeros in more precisely on De Niro's Jon Rubin as chameleon:

In the final portion of the film, Jon seemingly becomes entrenched in domestic terrorism and decides to disguise himself as a 'square' by marrying. The artificiality of Jon's faux-domestic set-up recalls a '50s sitcom, underpinned by a Weathermen Underground-style bombing that's thoroughly of the '70s. Though few might characterise the director of Carrie (1976) and Scarface as explicitly political, De Palma applies scalpel-like cynicism toward Jon's flirtation with underground social movements. Perhaps it's a young leftist's frustration with insincerity within the movement.Still, little in Hi, Mom! is straightforward. In Greetings, De Niro's Jon was a draft-dodger; in Hi, Mom!, he's a veteran, seemingly displaced by his role in that war. Many comparisons have been made between this and De Niro's later role as a 'Nam vet in Taxi Driver (1976), but he's the real spiritual antecedent of another darkly comic role for Scorsese: Rupert Pupkin. Like the delusional wannabe of The King Of Comedy (1983), Jon is so phony he's almost earnest in his phoniness. This is evident in the final set-up, when Jon wrangles his way to the front of a television news broadcast about the explosion he himself devised. As with so much of De Palma's work, we are watching people who are watching other people; some of whom know they are being watched and act accordingly. The intended result is a sort of endless, empty hall of mirros; a media spectacle with no meaning.

Regarding Hi, Mom! now - either as a direct sequel to Greetings or simply as a madcap counterculture relic - it doesn't necessarily equate to coherent greatness. But it does hint at the ways in which De Palma, along with the best of his generation of filmmakers, could marry the arthouse and the commercial in their later work. When they applied teh radical stylings of their art film interests to make challenging mainstream cinema of the era, the New Hollywood flowered into being.

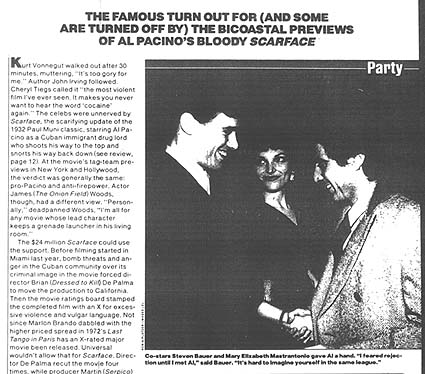

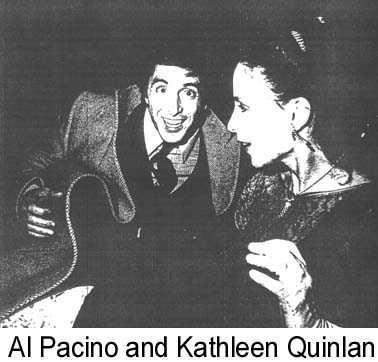

Pacino himself missed the New York preview because he was performing in a Broadway revival of David Mamet's American Buffalo, although he appears to have made it to the afterparty. In the photo to the left, Pacino is leaving the New York party by limo with his then-current girlfriend Kathleen Quinlan. In the photo at the top of this page, he is shaking hands with co-stars Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio and Steven Bauer. The caption underneath the photo quotes Bauer: "I feared rejection until I met Al. It's hard to imagine yourself in the same league."

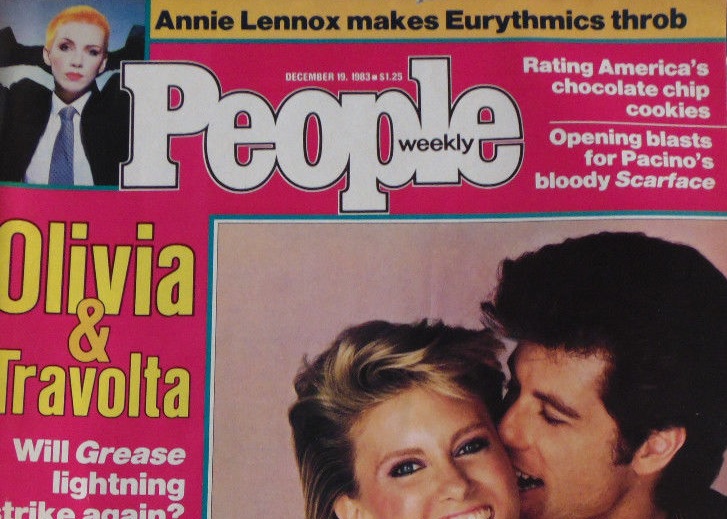

Pacino himself missed the New York preview because he was performing in a Broadway revival of David Mamet's American Buffalo, although he appears to have made it to the afterparty. In the photo to the left, Pacino is leaving the New York party by limo with his then-current girlfriend Kathleen Quinlan. In the photo at the top of this page, he is shaking hands with co-stars Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio and Steven Bauer. The caption underneath the photo quotes Bauer: "I feared rejection until I met Al. It's hard to imagine yourself in the same league." The article says that Lucille Ball was the favorite of fans watching from the sidewalk, until Eddie Murphy arrived to upstage her. Murphy is pictured at left with Diane Lane, who arrived late herself. Murphy said, "Al Pacino is my favorite actor. I know the dialogue to all his movies. When I met him, I groveled." The article says that the preview audience was more subdued after the screening, quoting Lucille Ball (whom the article consistently refers to as simply "Lucy") as saying, "We thought the performances were excellent, but we got awful sick of that word."

The article says that Lucille Ball was the favorite of fans watching from the sidewalk, until Eddie Murphy arrived to upstage her. Murphy is pictured at left with Diane Lane, who arrived late herself. Murphy said, "Al Pacino is my favorite actor. I know the dialogue to all his movies. When I met him, I groveled." The article says that the preview audience was more subdued after the screening, quoting Lucille Ball (whom the article consistently refers to as simply "Lucy") as saying, "We thought the performances were excellent, but we got awful sick of that word." Martin Bregman hosted an after-preview party for 130 guests at Sardi's in New York, where Cher, who brought her 14-year-old daughter Chastity along, told People, "I really liked it. It was a great example of how the American dream can go to shit." Raquel Welch, who also brought along her daughter Tahnee, said, "A lot of people will enjoy the comic-strip violence that goes on ad nauseam." Welch is also quoted in a photo caption as saying that "the violence is just for effect."

Martin Bregman hosted an after-preview party for 130 guests at Sardi's in New York, where Cher, who brought her 14-year-old daughter Chastity along, told People, "I really liked it. It was a great example of how the American dream can go to shit." Raquel Welch, who also brought along her daughter Tahnee, said, "A lot of people will enjoy the comic-strip violence that goes on ad nauseam." Welch is also quoted in a photo caption as saying that "the violence is just for effect." Another mother-daughter pair of interest showed up at the Los Angeles premiere: Tippi Hedren and daughter Melanie Griffith. Griffith at the time was married to Steven Bauer, and would go on to star in Brian De Palma's very next film in 1984, Body Double. According to the September 16 2003

Another mother-daughter pair of interest showed up at the Los Angeles premiere: Tippi Hedren and daughter Melanie Griffith. Griffith at the time was married to Steven Bauer, and would go on to star in Brian De Palma's very next film in 1984, Body Double. According to the September 16 2003

Something about Hans-Christoph Blumenberg's Rotwang muß weg! (1994) must have impressed Brian De Palma, because he agreed to appear in the German satire, billed in the credits as the "famous American movie director." The film itself has always been hard-to-find, but I located the images included in this post at

Something about Hans-Christoph Blumenberg's Rotwang muß weg! (1994) must have impressed Brian De Palma, because he agreed to appear in the German satire, billed in the credits as the "famous American movie director." The film itself has always been hard-to-find, but I located the images included in this post at

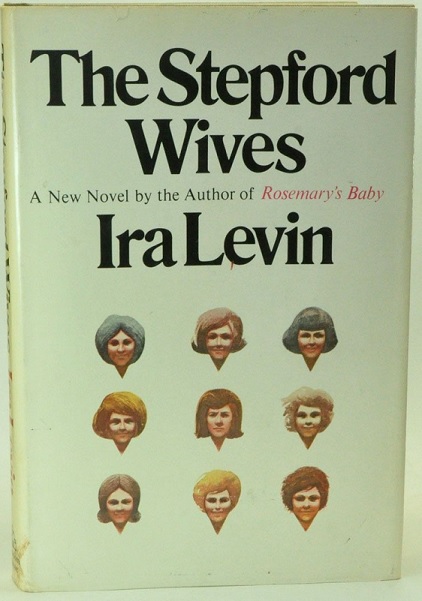

Brian De Palma has cited the dream sequence in Roman Polanski's adaptation of Ira Levin's Rosemary's Baby as the key inspiration for the exposition sequence in Sisters. One can imagine De Palma's enthusiasm when, soon after, a producer (Edgar J. Sherick) let him read the screenplay for another Levin adaptation, The Stepford Wives, with hopes of De Palma directing. The screenplay was written by William Goldman, who, sadly,

Brian De Palma has cited the dream sequence in Roman Polanski's adaptation of Ira Levin's Rosemary's Baby as the key inspiration for the exposition sequence in Sisters. One can imagine De Palma's enthusiasm when, soon after, a producer (Edgar J. Sherick) let him read the screenplay for another Levin adaptation, The Stepford Wives, with hopes of De Palma directing. The screenplay was written by William Goldman, who, sadly,