IF YOU HAVE 3 HOURS TO KILL (PLUS 7 MINUTES)

Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | July 2016 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | |||||

| 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

| 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 |

| 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 |

| 31 | ||||||

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

Shout! Factory yesterday finally revealed the extras that will be included on its collector's edition Blu-ray of Brian De Palma's Raising Cain, and they are fantastic. There will be a second disc, which will include a so-called "Director's Cut" of the film "Featuring Scenes Reordered As Originally Intended," which was put together by our old friend Peet Gelderblom (the same friend, by the way, who designed the "De Palma a la Mod" logo at the top of this very page). Also included will be an updated version of Peet's video essay about the Re-Cut (as it was originally called), as well as "Changing Cain: Brian De Palma's Cult Classic Restored Featurette," which you can actually watch right now at Directorama, along with a new written essay by Peet describing how it all came together. Other extras include brand new interviews with cast and Paul Hirsch-- check it out in full below. The collection will be released September 13th.

Shout! Factory yesterday finally revealed the extras that will be included on its collector's edition Blu-ray of Brian De Palma's Raising Cain, and they are fantastic. There will be a second disc, which will include a so-called "Director's Cut" of the film "Featuring Scenes Reordered As Originally Intended," which was put together by our old friend Peet Gelderblom (the same friend, by the way, who designed the "De Palma a la Mod" logo at the top of this very page). Also included will be an updated version of Peet's video essay about the Re-Cut (as it was originally called), as well as "Changing Cain: Brian De Palma's Cult Classic Restored Featurette," which you can actually watch right now at Directorama, along with a new written essay by Peet describing how it all came together. Other extras include brand new interviews with cast and Paul Hirsch-- check it out in full below. The collection will be released September 13th.DISC ONE:

-Theatrical Version Of The Film

-NEW Interviews With Actors John Lithgow, Steven Bauer, Gregg Henry, Tom Bower, Mel Harris And Editor Paul Hirsch

-Original Theatrical Trailer

DISC TWO:

-Director's Cut Of The Film Featuring Scenes Reordered As Originally Intended

-NEW Changing Cain: Brian De Palma's Cult Classic Restored Featurette

-NEW Raising Cain Re-Cut – A Video Essay By Peet Gelderblom

At Zekefilm, several critics chose a Brian De Palma film they had never seen previously, watched it, and then wrote about it. Their critiques are collected on one page. Here are some excerpts:

At Zekefilm, several critics chose a Brian De Palma film they had never seen previously, watched it, and then wrote about it. Their critiques are collected on one page. Here are some excerpts:"So, again, the Vertigo-ish aspects of Obsession are all but inescapable for those familiar with the earlier masterpiece, but like his later, overtly Psycho-influenced thriller Dressed to Kill (1980), De Palma adds problematic layers undreamt of by The Master. Indeed, the swirling camera around Courtland and his 're-found' lost love in a deliriously-lit airport lobby may be an almost exact copy of the most famous shot from Vertigo; however, the further provocative elements offered by De Palma’s Obsession make the act of 'viewing' the scene even more disturbing than Hitchcock himself intended."

Robert Hornak on Casualties Of War

"The contrast between the two [Sean Penn's Merserve and Michael J. Fox' Eriksson] has the effect of infusing everything with a certain cartoony two-dimensionality. But it works, insofar as this true story is beaten out into a morality tale about America – who it wants to be, coming face to face with who it might really be."

[Note: Contrast the above quote with the one from the other day about Blow Out, by Taylor Burns at Little White Lies: "Blow Out’s genius is to present the difference between what a country believes itself to be, and what it actually is. No matter the country. No matter who’s in charge."]

Sharon Autenrieth on Mission: Impossible

"I need someone who appreciates Brian De Palma’s style to walk me through a shot by shot study of Mission: Impossible so that I can get it."

Max Foizey on Phantom Of The Paradise

"I wholeheartedly agree with that library clerk and I’m sorry that I put off watching Phantom for as long as I did. Even being a fan of De Palma’s films, it was easy to shove Phantom off to the side. On the surface it seems so very unlike the rest of his work. When you think DePalma, you think sensuality, violence, and Hitchcock; you don’t think glam musical. But you should! Phantom of the Paradise is a De Palma film through and through, but with a mean satirical twist. It’s got horror, split screen, and voyeurism. Who else could have made this film? Nobody."

David Strugar on The Untouchables

"For me, many elements of the film have aged, not badly, but oddly. It’s a mystery to me now how Kevin Costner got famous, but his attractive dullness works here to portray the morally upright Elliot Ness. The whole storyline of a police force fighting its own corruption is suddenly timely again, as well as the ethical questions of fighting violence with violence—or of fighting a crime that doesn’t necessarily have to be a crime."

Travolta’s Jack Terry does everything his constitution tells him is the right thing to do, and he is punished for it, slapped back into place for having a blue collar and empty pockets. The information he has is of value to the American people and he pays for it with his life – not literally, like his partner, Sally (Nancy Allen), but with his American life, with the things he needs to know and trust to continue living as a citizen of his country. He ends the film alive but far from well. This is the politics of despair.The film’s tragic final scene is among the most sorrowful, albeit gorgeous, in all of cinema; the (fictional) Liberty Day parade provides a cruel and ironic backdrop to Terry’s crack-up, Travolta matching the tone of the story by twisting and turning through a Philadelphia seaport awash with red, white and blue. Thousands of everyday patriots have taken to the street while in the shadows a government fixer (John Lithgow) is killing a young woman, disavowing the basic principles on which America was founded. Blow Out’s genius is to present the difference between what a country believes itself to be, and what it actually is. No matter the country. No matter who’s in charge.

Throughout this climactic scene cymbals crash and fireworks bang. They hang in the sky, colourful bursts of unadulterated patriotism for the revellers below to gawp in awe at. These people have been sold the belief that if they work hard for their country, if they defend its constitution and serve its enforcers, they will be rewarded – in this case with a showy parade that literally reminds them of the “Liberty” they are supposed to be so grateful for. What they don’t see is the firework coming down as a damp squib; its light a mere distraction from what’s going on in the dark.

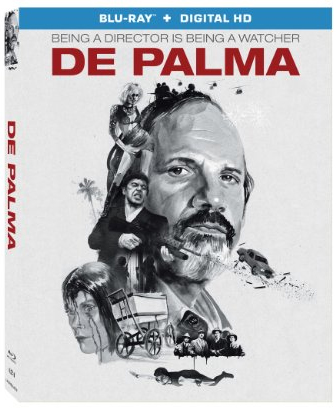

Earlier this week, it was announced that De Palma, the documentary co-directed by Noah Baumbach and Jake Paltrow, will be released on Blu-ray by Lionsgate on September 13th, two days after Brian De Palma's 76th birthday. According to Blu-ray.com, the running time is 107 minutes, which matches the theatrical version (curiously, the Amazon listing for the Blu-ray lists 93 minutes). No extras have been mentioned yet.

Earlier this week, it was announced that De Palma, the documentary co-directed by Noah Baumbach and Jake Paltrow, will be released on Blu-ray by Lionsgate on September 13th, two days after Brian De Palma's 76th birthday. According to Blu-ray.com, the running time is 107 minutes, which matches the theatrical version (curiously, the Amazon listing for the Blu-ray lists 93 minutes). No extras have been mentioned yet.

Thanks to Patrick for translating the following passage for us, from the June 2016 issue of Cahiers du Cinéma-- it's Cyril Béghin writing about Nicolas Winding Refn's Neon Demon:

Thanks to Patrick for translating the following passage for us, from the June 2016 issue of Cahiers du Cinéma-- it's Cyril Béghin writing about Nicolas Winding Refn's Neon Demon:Only God Forgives was already searching for a collage of archetypal or primal scenes, but Refn goes further this time, yielding only very little to the sirens of the genre and instead crystallizing clear and solitary visions that coexist and create a sequence of heterogeneous spaces for Jesse to circulate through. Thus the distant sensation his film owes even more to Carrie than to Mario Bava or Valley of the Dolls: when Jesse appears to float in the air, at the edge of a diving board, she recalls the omnipotent levitation of De Palma's adolescent, which is at the same time the invention of an image, aerial statue or demon of neon.

As we gear up for the upcoming Blu-ray sets of Brian De Palma's Raising Cain, Birth. Movies. Death.'s Jacob Knight writes about the film in the latest edition of his bi-weekly column, "Everybody's Into Weirdness"...

As we gear up for the upcoming Blu-ray sets of Brian De Palma's Raising Cain, Birth. Movies. Death.'s Jacob Knight writes about the film in the latest edition of his bi-weekly column, "Everybody's Into Weirdness"...Brian De Palma loves to make movies that act as funhouse mirror reflections of one another. Carlito’s Way could be interpreted as he and Al Pacino’s tear soaked apology letter, pleading for redemption after the wanton, bloated excess of Scarface. Redacted is a found footage update of Casualties of War, reminding us that combat can often act as a warm blanket for society’s greatest monsters. Obsession and Body Double find De Palma returning to the well of Vertigo, the motion picture that helped his brain fuse its understanding of functional mechanics with a need to tell tales of possessive madness. Nevertheless, none of the pairings quite complement each other like Raising Cain and Dressed to Kill. Building on his tendency toward first-person trash art with reckless abandon, Cain is a dream state rehash of Hithcock’s Psycho, tossed into a cinematic blender with Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom. An in-joke seemingly told only for the hardcore heads and his own amusement, De Palma’s nineteenth feature is a formal marvel that is in dialogue with the thriller dialect its author had perfected over the past twenty years.

For TIFF, which is currently in the middle of a Brian De Palma retrospective, Haley Mlotek has written a piece about Brian De Palma that looks at his aesthetic via the erotic thrillers Sisters, Dressed To Kill, Body Double, and Passion. Here are the introductory paragraphs:

For TIFF, which is currently in the middle of a Brian De Palma retrospective, Haley Mlotek has written a piece about Brian De Palma that looks at his aesthetic via the erotic thrillers Sisters, Dressed To Kill, Body Double, and Passion. Here are the introductory paragraphs:Film is perverse, and filmmakers are a special kind of pervert. They’re often presumed to be Peeping Toms, voyeurs with hard-ons for dark theatres and unnoticed gazes, but I’ve never known a filmmaker who likes action without their direction. They’re freaks for control, their preferred kink the crafting of an entire world that resembles a much better (or more fuckable) version of reality. They know what real life looks like — with its meandering plots and maddeningly open-ended storylines — and have chosen, instead, to find pleasure within celluloid correctives.Filmgoers, on the other hand: we’re the ordinary perverts. We like to watch in the dark, and we like being told what to like. Our preferences guide us to the ticket counter, but part of the point of those darkened theatres, with their insulated walls and cushioned seats, is to get the privacy we need to find something new for our wants, our needs, our boners.

Brian De Palma, whose films are playing as part of a retrospective this summer at the TIFF Bell Lightbox, doesn’t find the new erotic. He likes old — old ideas, old references, his ideas about sex, violence and gender worn in like a vintage leather glove on our sweaty palms. De Palma’s films like Sisters, Dressed to Kill, Body Double and Passion, are his most frequently invoked erotic thrillers, although many of his other films, which span genres like crime (Scarface), horror (Carrie) or psychological thriller (Raising Cain) include elements of the erotic, even when not intended to be explicitly so.

The movies, De Palma knows, are all sex. It’s the sluttiest medium. In her essay “The Decay of Cinema,” Susan Sontag eulogized what she saw as the inevitable death of film and cinephilia, saying that, “No amount of mourning will revive the vanished rituals — erotic, ruminative — of the darkened theater.” Perhaps not, but sorrow can be kind of hot. Mourning, in its most naked form, is an ache for something you’ve lost, and what’s more erotic than wanting what you can’t have?

In his interview with Chris Dumas, the author of Un-American Psycho: Brian De Palma and the Political Invisible, Adam Nayman wrote of De Palma’s obsession with failure, both personal and political. “De Palma empathizes with characters (typically, men) whose inability to act, despite their moral certainty that they should, results in collateral damage,” wrote Nayman. “It’s typically embodied by a woman that will haunt them after the final fade out.”

The De Palma erotic thriller that is my favorite is Passion (2012), the most recent addition to his personal sub-canon. It’s a dreamy and nonsensical story about Christine (Rachel McAdams, completely perfect in the strangest film wardrobe I’ve ever seen: jewel-toned skintight turtlenecks with wide silk trousers, red brocade dresses and matching lip gloss), an insatiable advertising executive with a hot boyfriend and an even hotter junior associate, Isabelle. (Noomi Rapace, her black bangs cut with the same precision as her tailored black suits). Isabelle is fucking Christine’s boyfriend, Dirk. Christine is trying to fuck Isabelle, both literally and professionally: she steals one of Isabelle’s ideas before a big meeting, which is hot in only the way subtly aggro, overtly passive displays of female dominance can be hot. Those same principles apply to the scene when Christine makes Isabelle wear the same shade of red lipstick to a work function.When Christine is murdered — another female lead down Janet Leigh’s shower drain — Isabelle becomes the suspect. Stealing another woman’s man and stealing her idea seem to be morally equivalent, providing a motive. Before the murder, Dirk tells Isabelle that Christine is, in bed, exactly as she is in real life, one rare moment where De Palma diverts from his expected modus operandi. Previously, his erotic thrillers were about characters who, in bed, were the people they wanted but couldn’t be in real life. Motive is its own kink in Passion, each character unsure of which jealousy prompted which violent crime: do Isabelle and Christine want each other, or just want to be each other?

Maybe De Palma thinks we’ll intuitively know how to answer that. His films are simple only in a Freudian sense, another favorite reference for filmmakers. In his erotic thrillers, the unknowable is the unfuckable. What his characters don’t understand, or can’t face, about their own identities, is what turns them into murderers. What his characters can’t see or find out about their own lives is what might make them victims. That’s why they’re given twins, or mirrored surfaces, or outfit changes to play opposite their personas. That’s why they’re watched, stalked and analyzed both in the film and by the audience. That’s what De Palma wants for us, the one experience neither filmmaker nor filmgoer will ever achieve despite our best efforts or best homages. In De Palma’s world, the best possible kink is the one just out of reach: to go fuck ourselves.