Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | July 2016 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | |||||

| 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

| 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 |

| 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 |

| 31 | ||||||

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

For TIFF, which is currently in the middle of a Brian De Palma retrospective, Haley Mlotek has written a piece about Brian De Palma that looks at his aesthetic via the erotic thrillers Sisters, Dressed To Kill, Body Double, and Passion. Here are the introductory paragraphs:

For TIFF, which is currently in the middle of a Brian De Palma retrospective, Haley Mlotek has written a piece about Brian De Palma that looks at his aesthetic via the erotic thrillers Sisters, Dressed To Kill, Body Double, and Passion. Here are the introductory paragraphs:Film is perverse, and filmmakers are a special kind of pervert. They’re often presumed to be Peeping Toms, voyeurs with hard-ons for dark theatres and unnoticed gazes, but I’ve never known a filmmaker who likes action without their direction. They’re freaks for control, their preferred kink the crafting of an entire world that resembles a much better (or more fuckable) version of reality. They know what real life looks like — with its meandering plots and maddeningly open-ended storylines — and have chosen, instead, to find pleasure within celluloid correctives.Filmgoers, on the other hand: we’re the ordinary perverts. We like to watch in the dark, and we like being told what to like. Our preferences guide us to the ticket counter, but part of the point of those darkened theatres, with their insulated walls and cushioned seats, is to get the privacy we need to find something new for our wants, our needs, our boners.

Brian De Palma, whose films are playing as part of a retrospective this summer at the TIFF Bell Lightbox, doesn’t find the new erotic. He likes old — old ideas, old references, his ideas about sex, violence and gender worn in like a vintage leather glove on our sweaty palms. De Palma’s films like Sisters, Dressed to Kill, Body Double and Passion, are his most frequently invoked erotic thrillers, although many of his other films, which span genres like crime (Scarface), horror (Carrie) or psychological thriller (Raising Cain) include elements of the erotic, even when not intended to be explicitly so.

The movies, De Palma knows, are all sex. It’s the sluttiest medium. In her essay “The Decay of Cinema,” Susan Sontag eulogized what she saw as the inevitable death of film and cinephilia, saying that, “No amount of mourning will revive the vanished rituals — erotic, ruminative — of the darkened theater.” Perhaps not, but sorrow can be kind of hot. Mourning, in its most naked form, is an ache for something you’ve lost, and what’s more erotic than wanting what you can’t have?

In his interview with Chris Dumas, the author of Un-American Psycho: Brian De Palma and the Political Invisible, Adam Nayman wrote of De Palma’s obsession with failure, both personal and political. “De Palma empathizes with characters (typically, men) whose inability to act, despite their moral certainty that they should, results in collateral damage,” wrote Nayman. “It’s typically embodied by a woman that will haunt them after the final fade out.”

The De Palma erotic thriller that is my favorite is Passion (2012), the most recent addition to his personal sub-canon. It’s a dreamy and nonsensical story about Christine (Rachel McAdams, completely perfect in the strangest film wardrobe I’ve ever seen: jewel-toned skintight turtlenecks with wide silk trousers, red brocade dresses and matching lip gloss), an insatiable advertising executive with a hot boyfriend and an even hotter junior associate, Isabelle. (Noomi Rapace, her black bangs cut with the same precision as her tailored black suits). Isabelle is fucking Christine’s boyfriend, Dirk. Christine is trying to fuck Isabelle, both literally and professionally: she steals one of Isabelle’s ideas before a big meeting, which is hot in only the way subtly aggro, overtly passive displays of female dominance can be hot. Those same principles apply to the scene when Christine makes Isabelle wear the same shade of red lipstick to a work function.When Christine is murdered — another female lead down Janet Leigh’s shower drain — Isabelle becomes the suspect. Stealing another woman’s man and stealing her idea seem to be morally equivalent, providing a motive. Before the murder, Dirk tells Isabelle that Christine is, in bed, exactly as she is in real life, one rare moment where De Palma diverts from his expected modus operandi. Previously, his erotic thrillers were about characters who, in bed, were the people they wanted but couldn’t be in real life. Motive is its own kink in Passion, each character unsure of which jealousy prompted which violent crime: do Isabelle and Christine want each other, or just want to be each other?

Maybe De Palma thinks we’ll intuitively know how to answer that. His films are simple only in a Freudian sense, another favorite reference for filmmakers. In his erotic thrillers, the unknowable is the unfuckable. What his characters don’t understand, or can’t face, about their own identities, is what turns them into murderers. What his characters can’t see or find out about their own lives is what might make them victims. That’s why they’re given twins, or mirrored surfaces, or outfit changes to play opposite their personas. That’s why they’re watched, stalked and analyzed both in the film and by the audience. That’s what De Palma wants for us, the one experience neither filmmaker nor filmgoer will ever achieve despite our best efforts or best homages. In De Palma’s world, the best possible kink is the one just out of reach: to go fuck ourselves.

On his podcast this week, Bret Easton Ellis opens with a great riff on the backlash to Art Tavana's think piece about the upfront sex appeal of Sky Ferreira in LA Weekly, and then links it to the new De Palma documentary by wondering how the politically-correct backlashers (Teen Vogue et al.) would react to the sexual politics and violence on display in the average Brian De Palma film. Ellis calls Noah Baumbach and Jake Paltrow's documentary "the most enjoyable movie I’ve seen so far in 2016." Here's a bit of partial transcript from his podcast review:

On his podcast this week, Bret Easton Ellis opens with a great riff on the backlash to Art Tavana's think piece about the upfront sex appeal of Sky Ferreira in LA Weekly, and then links it to the new De Palma documentary by wondering how the politically-correct backlashers (Teen Vogue et al.) would react to the sexual politics and violence on display in the average Brian De Palma film. Ellis calls Noah Baumbach and Jake Paltrow's documentary "the most enjoyable movie I’ve seen so far in 2016." Here's a bit of partial transcript from his podcast review:De Palma’s self-aware voyeuristic relationship to not only his female characters, but the medium itself, like Hitchcock’s, was what gave his films a jolt, and made his films so endlessly fascinating, and complicated, as well as how technically facile and inventive De Palma dealt with the medium itself. De Palma’s perversity in staging violence was witty and very cinematic. I can’t think of a moment of realistic violence in a De Palma film… the stabbing in Sisters, the pig’s blood and the massacre at the prom in Carrie, Fiona Lewis spinning to her death, midair, and John Cassavetes exploding in The Fury, the elevator slashing in Dressed To Kill, the chainsaw sequence in Scarface. And all of this done on a grand scale that will never be replicated in movies again. Yes, this was the 1970s when De Palma started making a string of great films, with Carrie probably being his go-to masterpiece, and one of the key films of the New Hollywood. Though with each successive viewing of De Palma’s 1981 John Travolta conspiracy thriller, Blow Out, I’m not totally positive about that anymore. Though Blow Out is Quentin Tarantino’s favorite movie. My own personal faves from him remain Phantom Of The Paradise and Dressed To Kill, where the killer is a tormented, pre-op transexual. Oh my God, oh my God, I just heard the Teen Vogue staff self-immolating......There’s only one medium shot of Brian De Palma talking that we return to throughout the documentary, in the same room, in the same blue shirt, but the majority of the movie is a brilliant and seamless array of clips from De Palma’s movies, and it is a visually overwhelming experience. I had not seen some of these images on a big screen in decades, and I was in awe. Oh, my God, movies used to look like that. De Palma says at one point about him and Spielberg and George Lucas, and Coppola and Scorsese, the directors who led the New Hollywood revolution in the 1970s, that this kind of moment, this auteurist freedom played out within the studio system, with directors making films for adults, will never return. And it reminds us that it was over almost before it began. De Palma reminds us that it wasn’t Jaws or Star Wars that ended the New Hollywood (aesthetically, they are examples of it), it was actually (as John Carpenter pointed out a couple of weeks ago) the failure of one of the grandest auteur movies ever made by a studio, Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate, that closed the door on an era. I don’t want to be a nostalgist, and neither does De Palma, but I feel a deep sense of loss comparing the movies then with the movies now.

John McMartin, who had a brief but pivotal role as a political advisor in Brian De Palma's Blow Out, has died at the age of 86. Variety's Gordon Cox notes that McMartin's death "was attributed to cancer in a paid obituary announcement in the New York Times." McMartin was memorable in a brief scene near the beginning of Blow Out in which his character convinces Jack Terry to go along with the official story of the car crash. McMartin appeared in many roles on Broadway and television, as well as film. According to The Film Experience, McMartin appeared in three films with Robert Redford, including Alan J. Pakula's All the President's Men.

John McMartin, who had a brief but pivotal role as a political advisor in Brian De Palma's Blow Out, has died at the age of 86. Variety's Gordon Cox notes that McMartin's death "was attributed to cancer in a paid obituary announcement in the New York Times." McMartin was memorable in a brief scene near the beginning of Blow Out in which his character convinces Jack Terry to go along with the official story of the car crash. McMartin appeared in many roles on Broadway and television, as well as film. According to The Film Experience, McMartin appeared in three films with Robert Redford, including Alan J. Pakula's All the President's Men.

On Friday, Daily Grind House posted an article in which its contributors either pick their favorite Brian De Palma film, or the one they think deserves another look. The art pictured here, by Andy Vanderbilt, accompanied the article (you can see a bigger version there). In the article, you'll find a lot of Carrie, a lot of Body Double, some Phantom Of The Paradise, a little Dressed To Kill and The Fury, a little Sisters, Snake Eyes, etc., etc. For a sample, here's Brett Gallman on Obsession:

On Friday, Daily Grind House posted an article in which its contributors either pick their favorite Brian De Palma film, or the one they think deserves another look. The art pictured here, by Andy Vanderbilt, accompanied the article (you can see a bigger version there). In the article, you'll find a lot of Carrie, a lot of Body Double, some Phantom Of The Paradise, a little Dressed To Kill and The Fury, a little Sisters, Snake Eyes, etc., etc. For a sample, here's Brett Gallman on Obsession:While it was released earlier in 1976, Brian De Palma’s OBSESSION soon found itself in the shadow of CARRIE, meaning it was destined to be forever overlooked in the director’s oeuvre. In retrospect, it’s almost apt that these particular films arrived within months of each other because they capture a director at a crossroads. Over the course of the previous five years, De Palma had come to find a singular voice in films like SISTERS and PHANTOM OF THE PARADISE, and CARRIE feels like a culmination: this was the moment De Palma truly arrived.And yet, it wasn’t quite enough for Brian De Palma to just be Brian De Palma, as he found himself famously chasing the ghosts of Hitchcock. That chase was arguably never as furious (or obvious) as it is with OBSESSION, which finds De Palma and co-writer Paul Schrader circling VERTIGO (to the tune of a Bernard Herrmann score, no less). Cliff Robertson replaces Jimmy Stewart as the ill-fated, lovelorn man at the film’s center, a New Orleans real estate developer who loses his wife and daughter to a botched kidnapping scheme. Years later, he falls for and marries a woman who bears a striking resemblance to his dead wife, and déjà vu appropriately hangs thick as De Palma retraces Hitchcock’s steps.

The layers of familiarity are almost deceptive: it’d be easy to dismiss OBSESSION as De Palma’s fanboy attempt to ape his idol, especially since his devotion to recapturing Hitchcock’s sweeping, melodramatic aesthetic is almost slavish. However, it’s more a fitting decoy designed to lure an unsuspecting audience down a path that quickly veers into the sort of lurid territory that Hitchcock only implied. OBSESSION climaxes with a dizzying display of ambiguity, a sublime moment that rapturously lays bare the psychosexual preoccupations of its director. It can be argued that this, too, is the moment De Palma truly arrived — even if he only stepped out of Hitchcock’s shadow long enough to be caught in his own a few months later.

The only time I ever interviewed Brian De Palma was back in 2007 about his much-maligned Iraq war drama Redacted. The film used the fact-based story of American military personnel who’d raped and murdered an Iraqi woman to critique both the second Gulf war and the increasingly untrustworthy 21st Century visual culture that manufactured a narrative of images for international consumption. Given Redacted’s relentless focus on the politics of perception, I thought it would be good to start by paraphrasing one of the key lines in De Palma’s screenplay back at him. “Do you really think,” I asked one of the most notorious voyeurs in the history of cinema, “that it is ‘impolite to stare?'” The pause before De Palma replied seemed to go on forever. Instead of answering, he simply repeated the question — “is it impolite to stare?” — while looking me dead in the eye, to the point that I almost regretted asking it in the first place.

ADAM NAYMAN: WHAT IS INVOLVED IN CLAIMING — OR RE-CLAIMING — BRIAN DE PALMA AS A "POLITICAL FILMMAKER?” WHAT, IN YOUR OPINION, IS THE PRIMAL SCENE OF HIS "POLITICAL" SIDE? AND WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO SITUATE SOMEBODY RECOGNIZED AS A MAINSTREAM FILMMAKER WITHIN A COUNTERCULTURAL CONTEXT?Chris Dumas: Well, I'd say that it requires re-thinking what it means to be a "political" filmmaker. Before 1960 or so, I suppose it meant that you made movies like Salt of the Earth — serious, sober melodramas about injustice. Now, after 9/11, I guess it means documentaries, The Big Short or historical gestures like Selma. But in between, there was Godard, and the idea that cinematic form itself was political — the morality-of-the-tracking-shot idea. Godard made it okay to do political work inside the confines of genre, and that's the path that De Palma found.

Sisters, for example: it's hard not to admire the chutzpah of remaking Psycho with an African-American male in the Janet Leigh role, and with a crusading white feminist reporter in the Vera Miles role. Then the double chutzpah of the hopeless, the-system-always-wins ending. I guess that hopelessness, coupled with the attention to genre, is what makes it hard for some American cinephiles, mostly those of a certain age, to see De Palma as having a politics. Americans, especially white Americans, like happy endings. And American audiences don't like feeling like they've been the butt of a joke, which of course is the De Palma trademark.

As for the "primal scene" of his politics — I've always wanted to ask him about that. Was it when he was a teenager and got shot by a cop? You've probably heard that, here in the USA, the cops really like to shoot people. I'd imagine that surviving something like that would probably make you reflect on society a little bit.

ADAM: LET'S GO WITH THE SHOT-BY-A-COP IDEA. I WONDER IF ONE WAY TO START TALKING ABOUT GREETINGS AND HI, MOM! IS HOW THEY SITUATE THEMSELVES IN DIFFERENT WAYS AGAINST INSTITUTIONS AND AUTHORITY FIGURES, AND THE INTERSECTION OF PERSONAL AND POLITICAL GRIEVANCE. THEIR NARRATIVE WORLDS AND CHARACTERS — ESPECIALLY DE NIRO — ARE REFLECTIONS OF THE ANTI-ESTABLISHMENT ATTITUDE OF THE DIRECTOR. BUT THERE'S ALSO MORE THAN YOUTHFUL CYNICISM AT WORK IN THESE FILMS. I'D TAKE YOUR IDEA ABOUT GODARD AND REVERSE IT BY SAYING THEY SEEM TO BE STRAINING AGAINST GENRE, AND TRYING TO EXPLODE IT, FROM THE INSIDE OUT.

Chris: Possibly so, but what genre are they straining against? De Palma didn't really commit fully to Hitchcock until Sisters. I'd say, before that, he was less concerned with understanding those kinds of rules and techniques—he was still more Masculin/Feminin than Rear Window. He knew he didn't like The System, however that was defined (the police, the draft board). But authority figures, representatives of that system, were still at a remove. Like LBJ on the television in Greetings — they're not ordinary human beings yet, the way they are in Blow Out. He's not yet seeing the institutions as rickety structures produced by human weakness, but as something monolithic, imposed from above.

Anyway, youthful cynicism is different from the cynicism of the disappointed, disillusioned adult. What you get over time in De Palma, but not in the rest of his cohort (Scorsese, et al.), is the slow realization that things are actually even worse than you imagined. A friend of mine once met Oliver Stone, and he took the opportunity to ask him what it was like to work with De Palma. Stone grew thoughtful and replied that De Palma was the saddest man he'd ever met. Not sad as in pathetic, I think, but broken, past hope, depressive. Hi, Mom! isn't like that, but Sisters certainly is.

"Earlier this week I saw the documentary De Palma, a feature length interview with the great director Brian De Palma, whose many films [include] Carrie, Scarface and The Untouchables. It’s a terrific watch for film fans, but most notably, one is struck by De Palma’s detail-oriented craft and complete control. Every shot, camera movement and actor’s blocking is motivated by a larger artistic purpose, even as his films delve into some outright sleazy subject matter from time to time.

"Now readers are probably wondering what this all has to do with the latest provocation from Danish director Nicolas Winding Refn. I saw The Neon Demon right after De Palma. They seemed to be appropriate bedfellows: a movie about a filmmaker who walks the fine line between art and trash, and then a movie that hopefully does that itself. Instead, the deficiencies of The Neon Demon were thrown into stark relief. Nicolas Winding Refn, it turns out, is no Brian De Palma."

"I’ll be the first to admit that I am drawn to filmmakers who use cinema as a way of pushing buttons, and I am a fan of the outrageous and the extreme. When I saw De Palma, the new documentary about Brian De Palma and his filmography, it sent me scrambling to watch a number of his older films again. They are so familiar at this point, so well-worn, that it surprised me to see how new they still feel when I took a step back. The next day, I went to a screening of the latest film from Nicolas Winding Refn, and the back-to-back timing of the two films made me laugh. More than anything, this feels like Refn working in the genre that De Palma had largely to himself in the late ’70s and early ’80s before getting relegated to mere late-night Cinemax fodder."

"Any number of movies have been made about the depravity of Los Angeles and the moral vacuum of the illusion industries at that city’s heart. It’s virtually a genre of self-loathing all to itself, from Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard to Sofia Coppola’s The Bling Ring. Nicolas Winding Refn’s fashionista horror film The Neon Demon, which is something like the bastard offspring of Brian De Palma and David Cronenberg, with a dollop of David Lynch on the down-low, definitely belongs to that tradition. But The Neon Demon is a striking and unusual L.A. story in several respects, not least because most of it occurs indoors."

"The Neon Demon is a tale of jealousy and bitterness set in L.A.’s fashion world, and has more than a little bit in common, thematically and stylistically, with Darren Aronofsky’s Black Swan. There are continuing motifs involving blood, large panthers, stylized violence and skinny models with visible ribcages. I could see Brian De Palma watching The Neon Demon and thinking the director should’ve taken it down a notch."

Edward Douglas, New York Daily News

"Over the past few years, Refn has been given a lot of free reign as a cinematic craftsman in the vein of David Fincher, Stanley Kubrick and Brian De Palma. But viewers will quickly realize that the real stars of Refn's film are his cinematographer Natasha Braier and composer Cliff Martinez, whose beautiful shots and ambient score are often the saving graces of The Neon Demon. (Even Martinez's synth noodlings start to get tiring once you realize the movie isn't going anywhere you may have any interest in going.) As with many supermodels, The Neon Demon is gorgeous to the eye but ultimately quite vacant and shallow."

"I love Refn’s work and seeing The Neon Demon right after seeing the documentary De Palma was perfect. Brian De Palma was a filmmaker dedicated to a particular vision and he crafted his film with great care. Refn has that same obsession with that sense of cinematic craft. Both directors make films that at their core also seem to be about the act of making a film."

Randall King, Winnipeg Free Press

"While the film has components of sex and violence, do not expect some kind of Brian De Palma-esque thriller. Refn is one for long, lingering takes and slow buildups, steeping the audience in the existential horror of it all. But as unsavoury as the material is — be warned there is a necrophilia scene that makes the pervy 1996 Canadian movie Kissed look like a Disney film — one can’t deny the sheer potency of Refn’s painstakingly composed images, even if the cumulative impact of it all leaves one feeling as empty as the glamourous amazons populating the screen."

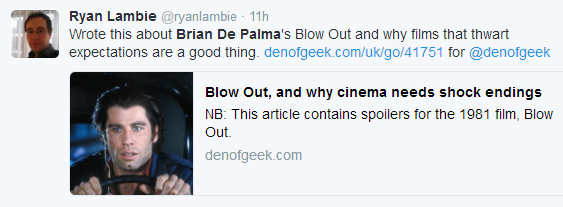

Den Of Geek's Ryan Lambie discusses how Brian De Palma's Blow Out shows why we need movies that challenge us...

Den Of Geek's Ryan Lambie discusses how Brian De Palma's Blow Out shows why we need movies that challenge us...It was through thinking about my initial, knee-jerk reaction to Blow Out that I realized how carefully crafted and outright brilliant De Palma’s film is. I’d seen the movie before as a teenager, but I’d failed to understand the true gravity of that ending I’ve been talking about for two or three paragraphs already. Watching it again about 20 years later, I finally felt the weight and heft of Blow Out’s downbeat climax, its political cynicism, and the totality of Jack’s failure in achieving the goals laid out for him as the film’s protagonist.De Palma didn’t make matters easy for himself by giving Blow Out such a bleak conclusion (he wrote the screenplay as well as directed). When the film came out in 1981, audiences appeared to vote with their wallets, with the warm recommendations from critics falling largely on deaf ears. Yet De Palma remained true to the movie he wanted to make; in the final analysis, Blow Out’s conclusion is as vital to its construction as the desolate resolution of David Fincher’s Seven.

In fact, there’s another potential reading of Blow Out that its director may or may not have consciously placed there for us: the movie is a master class in how to craft the perfect shock ending.

A tribute to the mechanics of filmmaking, yes, but Brian De Palma’s 1981 thriller also achieves a powerfully cynical evocation of America at the dawn of the Reagan era. Heavily influenced by the Watergate scandal, President John F. Kennedy’s assassination and other national tragedies, the movie builds to a Liberty Day celebration where patriotism is subsumed in madness, violence and inexorable tragedy.

Michael Cimino passed away on Saturday. He was 77.

Michael Cimino passed away on Saturday. He was 77.Thanks to Romain at the Virtuoso of the 7th Art for sending along an interesting paragraph from the October 2011 issue of Cahiers du Cinéma, which featured a cover story on Michael Cimino. For the issue, writer Jean-Baptiste Thoret journeyed with Cimino for three days between Los Angeles and Colorado, to see the landscapes of Cimino's cinema. On the trip, Thoret met Michael Stevenson, who was an assistant director on Cimino's Heaven's Gate. Stevenson told Thoret an interesting story, which Romain has kindly sent along to us:

I worked on Mission: Impossible with Brian De Palma. We came back from Roma, from a James Bond-like set, and we were going to shoot that scene on the train with Tom Cruise, Ving Rhames and Vanessa Redgrave. During a break, Brian sat on a chair and talked about cinema in general with his crew. Suddenly, Cimino's name came up. They knew I'd worked with him, so they invited me to join the conversation. Everybody was wondering why Cimino doesn't make movies anymore. Then, one of them said: "But is he really such a good film director?" De Palma shot daggers at him and told him, straight in the eye, with an icy calm: "The guy who made The Deer Hunter is a great filmmaker." That was the end of the conversation."

(Thanks to Romain!)