AT SARRIS-HOBERMAN DEBATE OVER 'DRESSED TO KILL'

Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | July 2016 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | |||||

| 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

| 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 |

| 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 |

| 31 | ||||||

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

At the Film Comment Blog, Margaret Barton-Fumo provides a critical overview of Ryuichi Sakamoto's career in film. Here's an excerpt covering Sakamoto's work with Brian De Palma:

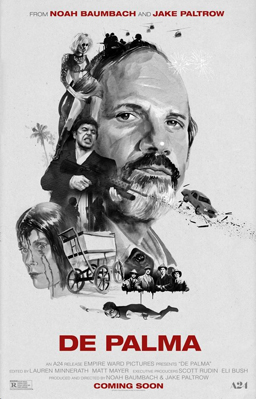

At the Film Comment Blog, Margaret Barton-Fumo provides a critical overview of Ryuichi Sakamoto's career in film. Here's an excerpt covering Sakamoto's work with Brian De Palma:A representative sampling of Sakamoto deep in the groove of his career comes with two films he scored for Brian De Palma, Snake Eyes (98) and Femme Fatale (02), both featured at Metrograph in a retrospective occasioned by the new documentary by Noah Baumbach and Jake Paltrow. Poignant and neo-classical, Sakamoto’s scores for these two films stage a fine counterpoint to the director’s unrelenting cynicism.De Palma’s noted cinephilia is evident in every detail of his work and his soundtracks are no exception. In Snake Eyes, Sakamoto’s leering, paranoid strings conjure some of Bernard Herrmann’s best-known scores for Hitchcock, while other cues sound more contemporary, with doses of reverb that add to the film’s oppressive claustrophobia. With a hurricane of near-Biblical proportions howling outside the labyrinthine casino setting, Sakamoto’s tasteful score affirms the film’s moral framework with ominous, weighted orchestral music underscoring the ham-fisted recurring image of a bloody $100 bill.

The score for Femme Fatale is also classically inclined with dashes of electronica in the secondary cues. Sakamoto’s creative re-working of Maurice Ravel’s “Bolero” (which at the time was not in the public domain), unsubtly titled “Bolerish,” is a delicately patchworked composition that accompanies the film’s opening jewel heist and closing slo-mo sequence in Paris. Not unlike the film itself, Sakamoto’s piece is an immaculate collage of clever rip-offs and deferential references. “Bolerish” softens the march of the Ravel piece into a graceful saunter that crosses the classical standard with other familiar melodies: Gato Barbieri’s Oscar-winning title theme for Last Tango in Paris makes a passing appearance, while Erik Satie’s “Gymnopédies” echo throughout. Sakamoto and De Palma have both described Femme Fatale as a “visual symphony,” and the prominence of “Bolerish” throughout the extended opening helps stage the heist sequence as the film’s grand overture. The essential pomp and plodding drive of the original “Bolero” remains in Sakamoto’s more serene version, controlling the pace (and supporting the refined atmosphere) of the Cannes-set jewelry heist.

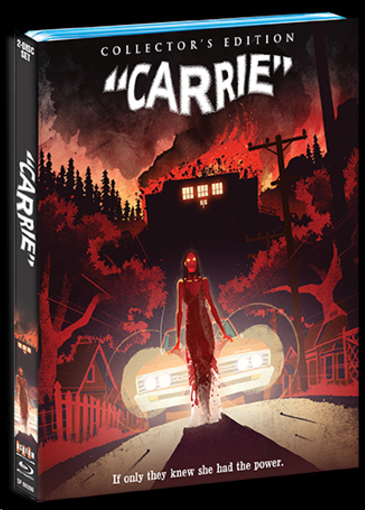

Shout! Factory today announced that it will release a 40th Anniversary two-disc Collector's Edition Blu-ray of Brian De Palma's Carrie on October 11th, just one month following Scream's Collector's Edition of De Palma's Raising Cain on September 13th. A Deluxe Limited Edition of Carrie will also be available (details below), and when preordered, it will arrive three weeks early. Here are all the details so far:

Shout! Factory today announced that it will release a 40th Anniversary two-disc Collector's Edition Blu-ray of Brian De Palma's Carrie on October 11th, just one month following Scream's Collector's Edition of De Palma's Raising Cain on September 13th. A Deluxe Limited Edition of Carrie will also be available (details below), and when preordered, it will arrive three weeks early. Here are all the details so far: The collector's edition Blu-Ray with slipcover

A limited edition 18" x 24" poster of the newly-designed art from artist Nat Marsh

A second slipcover — made exclusively for this promotion — featuring newly-designed art from artist Joel Robinson

A limited edition 18" x 24" poster of the newly-designed art from artist Joel Robinson

Early shipping to arrive three weeks before the national street date

Bonus Features

NEW 4K Scan Of The Original Negative

NEW Interviews With Writer Lawrence D. Cohen, Editor Paul Hirsch, Actors Piper Laurie, P.J. Soles, Nancy Allen, Betty Buckley, William Katt, Edie McClurg, Casting Director Harriet B. Helberg And Director Of Photography Mario Tosi

NEW Horror's Hallowed Grounds – Revisiting The Film's Original Locations

Acting Carrie – Interviews With Actors Sissy Spacek, Amy Irving, Betty Buckley, Nancy Allen, William Katt, Piper Laurie, Priscilla Pointer and P.J. Soles And Art Director Jack Fisk And Director Brian De Palma

Visualizing Carrie – Interviews With Brian De Palma, Jack Fisk, Lawrence D. Cohen, Paul Hirsch

A Look At "Carrie: The Musical"

Original Theatrical Trailer

Carrie Franchise Trailer Gallery

TV Spots

Radio Spots

Still Gallery – Rare Behind-The-Scenes Photos

Stephen King And The Evolution Of Carrie Text Gallery

Sissy Spacek’s blood-soaked rampage at the end of Carrie is so effective because it takes on the tone of a blackly comic fireworks display. Like the build up to a great, very grim joke, De Palma makes us anticipate Carrie White’s prom humiliation for several stomach-churning minutes: Amy Irving’s fellow pupil at the prom, spotting the rope that leads to the bucket of pig’s blood at the school prom. Nancy Allen licking her lips in expectation as she prepares to send the bucket of blood pouring all over poor Carrie’s head. The girl’s response, of course, is one of pure rage, and De Palma captures every moment of it in slow-motion, split-screen and intense red filters. It’s horrific, for sure, but there’s also a suggestion of slapstick in the electrocutions and fiery deaths. It's the friction between horror and black comedy, I'd suggest, that makes De Palma's work in Carrie and his other great films so effective - just as it did in Hitchcock's thrillers (the 2013 remake, by contrast, makes Carrie’s prom melt-down into a more straightforward horror sequence).The same fascination with the aesthetic power of comically outré violence is there in abundance in The Fury. A car chase in thick fog ends with a car flying off a jetty on fire. Robin uses his psychic powers to send a fairground ride spinning out of control, with distinctly messy results (for unexplained reasons, the ride is populated almost entirely by what appear to be princes from somewhere in the Middle East).

It’s in these scenes that De Palma’s baroque camera movements, which are largely low-key and understated during the scenes of exposition, suddenly come to the fore. A scene where Gillian demonstrates her supernatural powers on a train set could have been shot with a conventional series of cuts. Instead, De Palma uses a clever split-screen effect, which shows the train whistling by the camera in the lower half of the shot and Gillian’s staring, ice-blue eyes at the top. It’s an instance of De Palma producing a visual set-piece out of almost nowhere.

He pulls a similar feat near the film’s midpoint, where Gillian learns that the Paragon Institute she volunteered to join, and where Robin was also sent for a time, isn’t quite as idyllic as it first appears. While chatting to the seemingly benign Dr Cheever (Charles Durning), Gillian accidentally slips and grabs his hand to steady herself. As in Stephen King’s later The Dead Zone (adapted by David Cronenberg to memorable effect), this physical connection creates a psychic image of the future in Gillian’s mind. She sees Robin running from Dr. Cheever and falling from a window.

Again, De Palma uses a visual effect to put two pieces of action in one image: Amy Irving’s shot in front of a blue screen with the action projected behind her, thus allowing both foreground and background action to appear in focus. It’s only a brief moment, but it’s also a critical moment in the story, and De Palma’s filmmaking cleverly highlights it and underlines it twice.

Earlier this year, Owen Gleiberman published a book called Movie Freak: My Life Watching Movies, in which he passionately describes being struck by cinephilia as a young man during a screening of Brian De Palma's Carrie in 1976. Yesterday, after seeing the new documentary, De Palma, Gleiberman posted an essay at Variety with the headline, "Why I Can’t Love Brian De Palma (Though I’ve Always Wished I Could)." In the essay, Gleiberman again describes seeing Carrie, and how he nevertheless feels that De Palma's "'50s science nerd" background has led to a cinema that is usually too Brechtian to sweep him up the way Carrie does. Here's an excerpt:

Earlier this year, Owen Gleiberman published a book called Movie Freak: My Life Watching Movies, in which he passionately describes being struck by cinephilia as a young man during a screening of Brian De Palma's Carrie in 1976. Yesterday, after seeing the new documentary, De Palma, Gleiberman posted an essay at Variety with the headline, "Why I Can’t Love Brian De Palma (Though I’ve Always Wished I Could)." In the essay, Gleiberman again describes seeing Carrie, and how he nevertheless feels that De Palma's "'50s science nerd" background has led to a cinema that is usually too Brechtian to sweep him up the way Carrie does. Here's an excerpt:In 1976, the first time I saw “Carrie,” it was the most dramatic film experience of my life. The movie had the kind of impact on me that other people experienced with “The Exorcist” or “Jaws” — it made my head swivel around with fear and excitement, with the sheer cinematic fairy-tale pleasure of what I was seeing, and I lived inside the experience for months. It took over my very being. I, of course, went back and read the Stephen King novel on which “Carrie” was based, and saw that the film followed the book reasonably closely. Yet in no way did that detract, for me, from De Palma’s achievement. The movie as he directed it was a dream, a vision, a hallucination made real, from the poetic horror of that opening slow-motion sequence in the girls’ locker room (which seemed, at first, to be nakedly voyeuristic, though it was really quite the opposite, since the film invited such a powerful identification with Sissy Spacek’s Carrie that it effectively put you in the locker room right along with her) to the scenes between Carrie and her ragingly sensual evangelical mother that were like a fire-and-brimstone version of “The Glass Menagerie,” to the spangly pop rapture of the Cinderella-goes-to-the-prom plot to the drenching bloodbath that submerges the party in hell to the telekinetic nerd’s homicidal revenge that all added up to make “Carrie” the most primal movie ever made about American teenage life. My attitude toward De Palma became, in its way, quite simple: You are God! Now, please, give me more movies like that one!I didn’t realize that De Palma was not only not God, but that he was, in fact, a kind of genius tinkerer, a director with scruffy counterculture roots who was basically a recovering ’50s science nerd. He envisioned filmmaking as a series of technical challenges to be solved. This was still the mid-’70s, when no one quite realized that the New Hollywood was over. De Palma had been washed ashore amid the same wave of young guns that brought Coppola, Scorsese, Lucas, and Spielberg, and all five of them were famously friends with each other, and the other four certainly had a vision (Coppola the dark poet of the America dream-turned-nightmare, Scorsese the vérité rock & roller of street crime, Lucas the inventor/bard of pop-nostalgia culture, and Spielberg the wizard of the everyday fantastic who literally seemed to think with the camera). So it seemed only right to assume that De Palma had a vision, too.

One thing he definitely had — because it ran through so many of his films — was a series of interlocking obsessions: with Hitchcock, with the freedom and sleaze of the counterculture, with the voyeurism of image-making, with the JFK assassination and the whole secretive flavor of conspiracy. (“Carrie,” in its way, was a conspiracy movie.) It certainly felt like all that stuff added up to a vision, and when “The Fury,” De Palma’s first movie after “Carrie,” also featured a plot that spun around the stop-motion drama of the freak ailment/gift of telekinesis, that now seemed to be part of his vision too. Who was Brian De Palma? He was a scruffy voyeuristic Hitchcockian conspiracy buff who drenched love stories in blood and believed in the power of the id to move things! That seemed about as good a definition of a movie director as one needed.

It certainly was for Pauline Kael, the critic whose fervent obsession with De Palma became the lens through which a lot of people viewed him. After “Carrie,” I never really agreed with Kael about De Palma, yet his movies put her into such a responsive trance — and she wrote so entrancingly about them — that I always wished I could see a De Palma movie just the way Kael did: as a more “heightened” version of a Hitchcock thriller. But when I watched a film like “Dressed to Kill,” I experienced it as a Hitchcock pastiche. The luscious tracking-shot fulsomeness of the opening Museum of Modern Art pickup scene was like “Vertigo” on some very powerful downer drugs, and it was (for what seemed like 10 or 15 minutes) ravishing cinema…but it was the high point of the movie! The slasher in limp blonde hair and sunglasses made the film seem like a replay of “Psycho” starring Sandy Duncan, and what De Palma really seemed to be clueless about is that the cathartic shock effect of a killer brandishing a straight razor against a backdrop of staccato violins was no longer the stuff of artful suspense. It was the stuff of interchangeable mediocre slasher films that were feeding, parasitically, off the same “Psycho” aesthetic that he was.

In the opening moments of “De Palma,” De Palma talks about how Hitchcock first seized him, an anecdote that may reveal more about him than he knows. He recalls going to see “Vertigo” when it opened at Radio City Music Hall in 1958. He was 18 years old, and it hit him the same way that “Carrie” hit me: as a movie that blew away everything he had seen before. What spun his head around about “Vertigo,” in which James Stewart tries to turn a shop girl played by Kim Novak into the literal image of the woman he loved and lost (also played by Kim Novak), is that in De Palma’s eyes, it was a metaphor for what filmmakers do. They mold and shape what’s right in front of them until it matches the fantasy in their heads. This comparison, between the plot of “Vertigo” and what Hitchcock himself was up to as a filmmaker, has been noted before, but what’s striking is how front-and-center the Stewart/filmmaker parallel is in De Palma’s own experience of “Vertigo.” He says that this lends the movie a “Brechtian” dimension.

But I don’t think that’s how most people experience “Vertigo” — as a Brechtian metaphor for filmmaking. And while there’s nothing invalid about De Palma’s reading of the film, I think it accounts for the overwhelming difference between the kind of director Hitchcock was and the kind that De Palma turned out to be. Hitchcock, for all the macabre comedy of his public persona, was a dizzyingly romantic artist who, beneath his virtuosity, was often swooning; his films were fire-and-ice. De Palma, on the other hand, wasn’t heightening Hitchcock so much as adding a layer of ironic detachment to him, using cool camera movement to impersonate fire. I think that accounts for why the thrillers in which he recycles “Vertigo” (“Dressed to Kill,” “Body Double,” “Obsession”) never find an emotional grip — they’re larks of Brechtian menace. There’s a place for that in cinema, but “Carrie” is a Hitchcock film, and that’s because it’s the one De Palma film that really does swoon.

Richard Brody's June 2nd post at The New Yorker ("The Brian De Palma Conundrum") similarly considers that De Palma's scientific and Brechtian impulses have a tendency to distance the films from the viewer. "That’s why," Brody writes, "despite my often stunned admiration for many of De Palma’s creations, I think that he’s a director who’s more often fascinating than great." Brody states at the start, "I think that movies are a medium—in the spiritual or metaphysical sense of putting the souls of viewers into connection with the souls of filmmakers." Hence for De Palma to create works that inherently seem to distance the viewer from the filmmaker, is to work against the way Brody thinks movies should work. But even if De Palma deliberately creates works that go for a Brechtian distance (and perhaps Brody also thinks De Palma does not go deeply enough in that direction), can he not create a great work of art in that mode? At one point, Brody confusingly states that there is no reflexivity in De Palma's films, even though we see reflexivity all over the place in De Palma's cinema. Here's an excerpt from Brody:

That’s the enduring paradox of De Palma’s films. Coming of age in the nineteen-sixties, he reveals himself, in his films, to be enduringly skeptical of authority. He distrusts the official word and the official version, whether that officialdom is the government’s or the corporate media’s. Yet De Palma films from a position of authority derived from the authority of the filmmakers he studied and the styles he inherited. There’s no reflexivity in his films, no sense that the fictional schema that he creates is itself in need of puncturing, no attempt to look behind the camera or see off-screen, no prism and no mirror that breaks his own frame. Even his most original trope, the split-screen, in which he creates an audacious counterpoint of images, veers from a thrilling representation of modern-day information overload to the visual equivalent of academic composition, in which contrasts and clashes are downplayed in favor of coherence and consistency.There’s an incipient and unfulfilled Brechtianism in De Palma’s work—a sense that the most efficient way to reveal the truth is to display the artifice that goes into the telling. That’s why many of his movies, whether “Sisters” or “Obsession,” “The Fury” or “Dressed to Kill,” “Blow Out” or “Casualties of War” or “The Untouchables,” have, as their stories, the creation of stories, the development of elaborately fabricated false-narrative fronts to conceal misdeeds. Yet the extreme artifice of De Palma’s amazingly intricate visual confections and virtuosic creations calls attention to what he does, not to how he does it.

Thanks to the news page at the Swan Archives for noting that The Metrograph in New York City has extended its Brian De Palma series through June 30th, adding new screenings of Passion and Mission: Impossible (both tonight), as well as Femme Fatale (Monday), Raising Cain (Tuesday), the Bonfire Of The Vanities (Wednesday), Blow Out (Thursday), and Dressed To Kill (Thursday).

Thanks to the news page at the Swan Archives for noting that The Metrograph in New York City has extended its Brian De Palma series through June 30th, adding new screenings of Passion and Mission: Impossible (both tonight), as well as Femme Fatale (Monday), Raising Cain (Tuesday), the Bonfire Of The Vanities (Wednesday), Blow Out (Thursday), and Dressed To Kill (Thursday).Also keep an eye on Alamo Drafthouse Cinemas in Austin and around the country, as they are currently screening several De Palma films in select theaters.

And thanks to Hugh for letting us know that the Vancouver International Film Festival will feature a Brian De Palma series in July, consisting of thirteen De Palma features: Sisters, Phantom Of The Paradise, Obsession, Carrie, Dressed To Kill, Blow Out, Scarface, Body Double, The Untouchables, Carlito's Way, Mission: Impossible, Femme Fatale, and Passion.

One would assume De Palma reins in these aesthetic statements of intent for the bulk of a film concerned with plot, but it’s too giddily drunk on what opportunities genre filmmaking allows for experimentation. What sets Murder apart from say, Scorsese’s debut, Who’s That Knocking At My Door?, is an assurance that comes with De Palma’s handling of both camera and genre, demonstrating how intensely familiar he is with the archetypes at work and how easily, even at this nascent stage, he can pervert them. Much is taken from Psycho, including a subplot involving a stolen envelope of money — but, most interestingly, manipulation of voiceover to both elucidate and obscure character motivations revolving around the film’s central murder. Nonlinear narrative and vantage points are tampered with (although the transitions between these are the movie’s clunkiest moments), providing a ground zero for a significant facet of Quentin Tarantino’s oeuvre.Changes in film speed and stock are also among Murder à la Mod’s pleasures, indeed pointing to the influence both silent comedies and, more immediately, the French New Wave had on De Palma’s sensibilities; however, late-60s Truffaut, rather than Godard, strikes one as the greater figure looming over the film, with its attention to the rules of suspense. But aforementioned perversions of the precedents set by Hitchcock and others are what make De Palma’s cinema worthwhile. A noteworthy moment: as the camera is stealthily following Karen to the shower, a detour is taken around a corner to reveal an unidentified hand holding out an ominous clock for the audience to see. This digression exposes a key aspect of the way De Palma films thrillers: the camera (and, therefore, audience) is just as complicit in the gory violence enacted upon victims.

Otto is revealed to be the closest thing to an audience surrogate in the film’s climax — which takes place in a projection booth, naturally. He becomes an accidental murderer, through a mishap between a real and trick ice pick — a perfect metaphor for Brian De Palma’s prevailing style if ever there was one — and is genuinely bewildered by what he has done. He then happens upon Karen’s “photobiography,” which contains an image of her corpse, and hauntingly remarks, “A picture. He killed her and he put her in the picture.” In that indelible final moment, the induction of Brian De Palma as a significant cinematic voice is undeniable.