Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | June 2016 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

| 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 |

| 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | ||

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

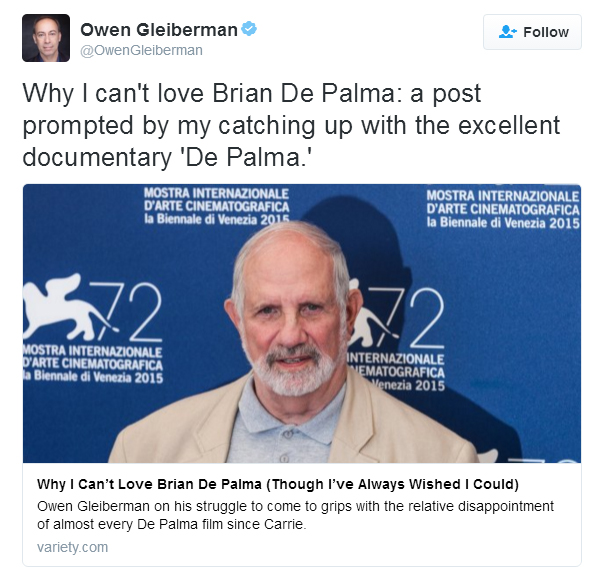

Earlier this year, Owen Gleiberman published a book called Movie Freak: My Life Watching Movies, in which he passionately describes being struck by cinephilia as a young man during a screening of Brian De Palma's Carrie in 1976. Yesterday, after seeing the new documentary, De Palma, Gleiberman posted an essay at Variety with the headline, "Why I Can’t Love Brian De Palma (Though I’ve Always Wished I Could)." In the essay, Gleiberman again describes seeing Carrie, and how he nevertheless feels that De Palma's "'50s science nerd" background has led to a cinema that is usually too Brechtian to sweep him up the way Carrie does. Here's an excerpt:

Earlier this year, Owen Gleiberman published a book called Movie Freak: My Life Watching Movies, in which he passionately describes being struck by cinephilia as a young man during a screening of Brian De Palma's Carrie in 1976. Yesterday, after seeing the new documentary, De Palma, Gleiberman posted an essay at Variety with the headline, "Why I Can’t Love Brian De Palma (Though I’ve Always Wished I Could)." In the essay, Gleiberman again describes seeing Carrie, and how he nevertheless feels that De Palma's "'50s science nerd" background has led to a cinema that is usually too Brechtian to sweep him up the way Carrie does. Here's an excerpt:In 1976, the first time I saw “Carrie,” it was the most dramatic film experience of my life. The movie had the kind of impact on me that other people experienced with “The Exorcist” or “Jaws” — it made my head swivel around with fear and excitement, with the sheer cinematic fairy-tale pleasure of what I was seeing, and I lived inside the experience for months. It took over my very being. I, of course, went back and read the Stephen King novel on which “Carrie” was based, and saw that the film followed the book reasonably closely. Yet in no way did that detract, for me, from De Palma’s achievement. The movie as he directed it was a dream, a vision, a hallucination made real, from the poetic horror of that opening slow-motion sequence in the girls’ locker room (which seemed, at first, to be nakedly voyeuristic, though it was really quite the opposite, since the film invited such a powerful identification with Sissy Spacek’s Carrie that it effectively put you in the locker room right along with her) to the scenes between Carrie and her ragingly sensual evangelical mother that were like a fire-and-brimstone version of “The Glass Menagerie,” to the spangly pop rapture of the Cinderella-goes-to-the-prom plot to the drenching bloodbath that submerges the party in hell to the telekinetic nerd’s homicidal revenge that all added up to make “Carrie” the most primal movie ever made about American teenage life. My attitude toward De Palma became, in its way, quite simple: You are God! Now, please, give me more movies like that one!I didn’t realize that De Palma was not only not God, but that he was, in fact, a kind of genius tinkerer, a director with scruffy counterculture roots who was basically a recovering ’50s science nerd. He envisioned filmmaking as a series of technical challenges to be solved. This was still the mid-’70s, when no one quite realized that the New Hollywood was over. De Palma had been washed ashore amid the same wave of young guns that brought Coppola, Scorsese, Lucas, and Spielberg, and all five of them were famously friends with each other, and the other four certainly had a vision (Coppola the dark poet of the America dream-turned-nightmare, Scorsese the vérité rock & roller of street crime, Lucas the inventor/bard of pop-nostalgia culture, and Spielberg the wizard of the everyday fantastic who literally seemed to think with the camera). So it seemed only right to assume that De Palma had a vision, too.

One thing he definitely had — because it ran through so many of his films — was a series of interlocking obsessions: with Hitchcock, with the freedom and sleaze of the counterculture, with the voyeurism of image-making, with the JFK assassination and the whole secretive flavor of conspiracy. (“Carrie,” in its way, was a conspiracy movie.) It certainly felt like all that stuff added up to a vision, and when “The Fury,” De Palma’s first movie after “Carrie,” also featured a plot that spun around the stop-motion drama of the freak ailment/gift of telekinesis, that now seemed to be part of his vision too. Who was Brian De Palma? He was a scruffy voyeuristic Hitchcockian conspiracy buff who drenched love stories in blood and believed in the power of the id to move things! That seemed about as good a definition of a movie director as one needed.

It certainly was for Pauline Kael, the critic whose fervent obsession with De Palma became the lens through which a lot of people viewed him. After “Carrie,” I never really agreed with Kael about De Palma, yet his movies put her into such a responsive trance — and she wrote so entrancingly about them — that I always wished I could see a De Palma movie just the way Kael did: as a more “heightened” version of a Hitchcock thriller. But when I watched a film like “Dressed to Kill,” I experienced it as a Hitchcock pastiche. The luscious tracking-shot fulsomeness of the opening Museum of Modern Art pickup scene was like “Vertigo” on some very powerful downer drugs, and it was (for what seemed like 10 or 15 minutes) ravishing cinema…but it was the high point of the movie! The slasher in limp blonde hair and sunglasses made the film seem like a replay of “Psycho” starring Sandy Duncan, and what De Palma really seemed to be clueless about is that the cathartic shock effect of a killer brandishing a straight razor against a backdrop of staccato violins was no longer the stuff of artful suspense. It was the stuff of interchangeable mediocre slasher films that were feeding, parasitically, off the same “Psycho” aesthetic that he was.

In the opening moments of “De Palma,” De Palma talks about how Hitchcock first seized him, an anecdote that may reveal more about him than he knows. He recalls going to see “Vertigo” when it opened at Radio City Music Hall in 1958. He was 18 years old, and it hit him the same way that “Carrie” hit me: as a movie that blew away everything he had seen before. What spun his head around about “Vertigo,” in which James Stewart tries to turn a shop girl played by Kim Novak into the literal image of the woman he loved and lost (also played by Kim Novak), is that in De Palma’s eyes, it was a metaphor for what filmmakers do. They mold and shape what’s right in front of them until it matches the fantasy in their heads. This comparison, between the plot of “Vertigo” and what Hitchcock himself was up to as a filmmaker, has been noted before, but what’s striking is how front-and-center the Stewart/filmmaker parallel is in De Palma’s own experience of “Vertigo.” He says that this lends the movie a “Brechtian” dimension.

But I don’t think that’s how most people experience “Vertigo” — as a Brechtian metaphor for filmmaking. And while there’s nothing invalid about De Palma’s reading of the film, I think it accounts for the overwhelming difference between the kind of director Hitchcock was and the kind that De Palma turned out to be. Hitchcock, for all the macabre comedy of his public persona, was a dizzyingly romantic artist who, beneath his virtuosity, was often swooning; his films were fire-and-ice. De Palma, on the other hand, wasn’t heightening Hitchcock so much as adding a layer of ironic detachment to him, using cool camera movement to impersonate fire. I think that accounts for why the thrillers in which he recycles “Vertigo” (“Dressed to Kill,” “Body Double,” “Obsession”) never find an emotional grip — they’re larks of Brechtian menace. There’s a place for that in cinema, but “Carrie” is a Hitchcock film, and that’s because it’s the one De Palma film that really does swoon.

Richard Brody's June 2nd post at The New Yorker ("The Brian De Palma Conundrum") similarly considers that De Palma's scientific and Brechtian impulses have a tendency to distance the films from the viewer. "That’s why," Brody writes, "despite my often stunned admiration for many of De Palma’s creations, I think that he’s a director who’s more often fascinating than great." Brody states at the start, "I think that movies are a medium—in the spiritual or metaphysical sense of putting the souls of viewers into connection with the souls of filmmakers." Hence for De Palma to create works that inherently seem to distance the viewer from the filmmaker, is to work against the way Brody thinks movies should work. But even if De Palma deliberately creates works that go for a Brechtian distance (and perhaps Brody also thinks De Palma does not go deeply enough in that direction), can he not create a great work of art in that mode? At one point, Brody confusingly states that there is no reflexivity in De Palma's films, even though we see reflexivity all over the place in De Palma's cinema. Here's an excerpt from Brody:

That’s the enduring paradox of De Palma’s films. Coming of age in the nineteen-sixties, he reveals himself, in his films, to be enduringly skeptical of authority. He distrusts the official word and the official version, whether that officialdom is the government’s or the corporate media’s. Yet De Palma films from a position of authority derived from the authority of the filmmakers he studied and the styles he inherited. There’s no reflexivity in his films, no sense that the fictional schema that he creates is itself in need of puncturing, no attempt to look behind the camera or see off-screen, no prism and no mirror that breaks his own frame. Even his most original trope, the split-screen, in which he creates an audacious counterpoint of images, veers from a thrilling representation of modern-day information overload to the visual equivalent of academic composition, in which contrasts and clashes are downplayed in favor of coherence and consistency.There’s an incipient and unfulfilled Brechtianism in De Palma’s work—a sense that the most efficient way to reveal the truth is to display the artifice that goes into the telling. That’s why many of his movies, whether “Sisters” or “Obsession,” “The Fury” or “Dressed to Kill,” “Blow Out” or “Casualties of War” or “The Untouchables,” have, as their stories, the creation of stories, the development of elaborately fabricated false-narrative fronts to conceal misdeeds. Yet the extreme artifice of De Palma’s amazingly intricate visual confections and virtuosic creations calls attention to what he does, not to how he does it.

Thanks to the news page at the Swan Archives for noting that The Metrograph in New York City has extended its Brian De Palma series through June 30th, adding new screenings of Passion and Mission: Impossible (both tonight), as well as Femme Fatale (Monday), Raising Cain (Tuesday), the Bonfire Of The Vanities (Wednesday), Blow Out (Thursday), and Dressed To Kill (Thursday).

Thanks to the news page at the Swan Archives for noting that The Metrograph in New York City has extended its Brian De Palma series through June 30th, adding new screenings of Passion and Mission: Impossible (both tonight), as well as Femme Fatale (Monday), Raising Cain (Tuesday), the Bonfire Of The Vanities (Wednesday), Blow Out (Thursday), and Dressed To Kill (Thursday).Also keep an eye on Alamo Drafthouse Cinemas in Austin and around the country, as they are currently screening several De Palma films in select theaters.

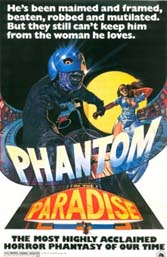

And thanks to Hugh for letting us know that the Vancouver International Film Festival will feature a Brian De Palma series in July, consisting of thirteen De Palma features: Sisters, Phantom Of The Paradise, Obsession, Carrie, Dressed To Kill, Blow Out, Scarface, Body Double, The Untouchables, Carlito's Way, Mission: Impossible, Femme Fatale, and Passion.

One would assume De Palma reins in these aesthetic statements of intent for the bulk of a film concerned with plot, but it’s too giddily drunk on what opportunities genre filmmaking allows for experimentation. What sets Murder apart from say, Scorsese’s debut, Who’s That Knocking At My Door?, is an assurance that comes with De Palma’s handling of both camera and genre, demonstrating how intensely familiar he is with the archetypes at work and how easily, even at this nascent stage, he can pervert them. Much is taken from Psycho, including a subplot involving a stolen envelope of money — but, most interestingly, manipulation of voiceover to both elucidate and obscure character motivations revolving around the film’s central murder. Nonlinear narrative and vantage points are tampered with (although the transitions between these are the movie’s clunkiest moments), providing a ground zero for a significant facet of Quentin Tarantino’s oeuvre.Changes in film speed and stock are also among Murder à la Mod’s pleasures, indeed pointing to the influence both silent comedies and, more immediately, the French New Wave had on De Palma’s sensibilities; however, late-60s Truffaut, rather than Godard, strikes one as the greater figure looming over the film, with its attention to the rules of suspense. But aforementioned perversions of the precedents set by Hitchcock and others are what make De Palma’s cinema worthwhile. A noteworthy moment: as the camera is stealthily following Karen to the shower, a detour is taken around a corner to reveal an unidentified hand holding out an ominous clock for the audience to see. This digression exposes a key aspect of the way De Palma films thrillers: the camera (and, therefore, audience) is just as complicit in the gory violence enacted upon victims.

Otto is revealed to be the closest thing to an audience surrogate in the film’s climax — which takes place in a projection booth, naturally. He becomes an accidental murderer, through a mishap between a real and trick ice pick — a perfect metaphor for Brian De Palma’s prevailing style if ever there was one — and is genuinely bewildered by what he has done. He then happens upon Karen’s “photobiography,” which contains an image of her corpse, and hauntingly remarks, “A picture. He killed her and he put her in the picture.” In that indelible final moment, the induction of Brian De Palma as a significant cinematic voice is undeniable.

Our old friend Bill Fentum was at The Majestic Theatre in Dallas this past Friday night (June 17), where Brian De Palma's Phantom Of The Paradise screened as part of this year's Oak Cliff Film Festival, with one of the film's stars, Jessica Harper, in attendance. The screening was a homecoming for Phantom, as parts of it were filmed at The Majestic, but it had never played there until last week. Here is Fentum's report, followed by a short YouTube video from Harper's Q&A, and then a link to a separate interview with Harper prior to the screening:

Our old friend Bill Fentum was at The Majestic Theatre in Dallas this past Friday night (June 17), where Brian De Palma's Phantom Of The Paradise screened as part of this year's Oak Cliff Film Festival, with one of the film's stars, Jessica Harper, in attendance. The screening was a homecoming for Phantom, as parts of it were filmed at The Majestic, but it had never played there until last week. Here is Fentum's report, followed by a short YouTube video from Harper's Q&A, and then a link to a separate interview with Harper prior to the screening:Jessica Harper remarked on how strange it felt to return to the place where much of Phantom was filmed, and the fun of watching the movie with so many fans in attendance, applauding for each song as well as the cast and De Palma in the end credits. The crowd included a guy from Memphis dressed as the Phantom with mask/helmet and cape [see YouTube video below], and several people who had traveled from Winnipeg for the occasion. They clearly enjoyed taking photos around the building (much of it looking the same today, despite renovations through the years), and Harper was invited during the Q&A to come to a Phantom screening event in Winnipeg this October 28, with the Juicy Fruits/Beach Bums/Undead trio—Archie Hahn, Jeffrey Comanor and Peter Elbling (Harold Oblong)—all scheduled to be there.Asked to share memories of the production, she talked about the energy that people like Hahn, Comanor, Elbling and George Memmoli brought to the set each day. Most touching, she talked the gentle support she received from William Finley throughout the shoot, making her debut film much easier than it might have been. She laughed about her "chicken dance" at the end of the "Special to Me" number ("my personal contribution to the choreography"), and recalled some conflict with costume designer Rosanna Norton, who didn't always welcome accessories Harper would add to her wardrobe, like the fedora she throws onto the stage in her "Special to Me" audition.

A couple of other memories: Steven Spielberg visiting the set in New York after the crew left Dallas, and besides Linda Ronstadt, her competition for the role of Phoenix including a then active singer named Lynn Carey, daughter of actor Macdonald Carey. Finally, asked about being directed by De Palma and other auteurs in her career (e.g., Dario Argento on Suspiria, Spielberg on Minority Report and Woody Allen on Love and Death and Stardust Memories), she noted that it always leads to a better experience than films where the director lacks a strong personal connection to the material, and isn't sure of what he wants.

Everybody has their own favorite song. I think a lot of people like "Old Souls," and not that I don't, but "Special to Me" is one of my favorite song-scenes in the film. I love the choreography of the dance. There's something just so enchanting about the whole thing. Do you remember how that came to be? The process of choreographing and all of that?I kind of made it up.

Really?

Oh, yeah. There was that kind of configuration of the stage where the piece of stage going out into the audience, a strip of stage so I had to move. I had to get from A to B to C and back again so I had to figure out something, some kind of thing I could do that would get me where I needed to go doing some kind of dancey thing that would accommodate the necessity. The famous chicken dance.

I think I just came up with it and I just started messing around on stage and made it work. I had this fedora. I think the costume designer really wanted to kill me because I kept saying, "I think I should wear this," or "I think I should wear this." I really misbehaved with the costume designer including, I brought this fedora in. It was something I wore in real life. I went around with this little fedora at that time. I thought, “This will be a great prop. I'm going to take this hat and I'm going to throw it out.” I like to take credit for that scene in terms of the choreography and the hat.

Well, it's very good work.

Thank you.

I just love it. Even the moments of calm, I guess the chorus, where you're just sort of staring into the camera, it's so hypnotizing. Do you have a favorite song or a favorite scene?

I love that scene. I also love "Old Souls" too. I think it's a beautiful song.

Indeed! (Guillermo del Toro and his wife danced to it at their wedding.)

I was so lucky I got to sing these gorgeous songs, but that was called for, of course. I really liked "Old Soul" and "Special to Me."

Do you recall one scene as being really fun to shoot?

"The freak who killed Beef is up on the roof.” I just remember finding that really hard to say. The freak who killed Beef is up on the roof.

That is a bit of a tongue twister.

That's something you can say three times fast.... Doing "Special to Me" could not have been more fun. Oh! You know what was fun - except it was really hair-raising? The first day of shooting we did all that stuff that was at the beginning where I come in and audition and there's this scene that's kind of hilarious where, first of all, I'm going up this staircase and Finley comes up and we meet and there's a spark.

And then there's the scene, which was also the first day of shooting on the first movie I'd ever done. (DePalma) said, "Hit your mark!" I didn't know! “Who's my Marc and why do I have to hit him?” I didn’t know what they were saying.

There's another scene where I was like in tears all the time. When I say it was fun I would say in addition it was also completely terrifying, because I didn't know anything. I had to run into the casting room, where George Memmoli is standing wearing a velour shirt and huge turquoise trunks, like underpants.

I had to go in there and then the door closed and there's a certain amount of commotion and I come screaming, tearing out of the room again, saying, you know, indignant things because he's obviously jumping on top of every actress who goes into the so-called casting chamber. “I came here to sing!” I can't remember what I said, but some indignant, full of myself remark.

That was just funny because George is so funny and it was just, you know. And again, just so fun because I was getting the hang of what you were supposed to do on a movie set, which up to that point I had absolutely no idea about.

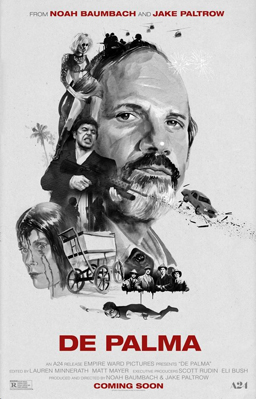

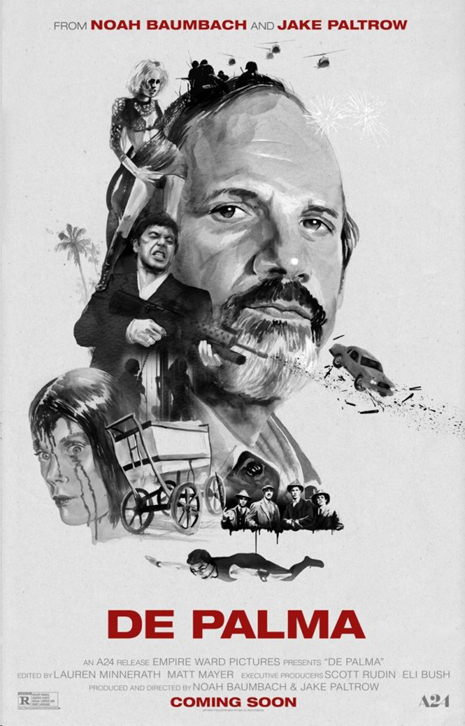

This new, second De Palma poster popped up today from A24. Meanwhile, in this week's issue of The New Yorker, Tad Friend sits in on a Thursday night dinner with Brian De Palma, Noah Baumbach, and Jake Paltrow:

This new, second De Palma poster popped up today from A24. Meanwhile, in this week's issue of The New Yorker, Tad Friend sits in on a Thursday night dinner with Brian De Palma, Noah Baumbach, and Jake Paltrow:Brian De Palma tucked his napkin under his chin and said, “I woke up in the middle of the night with this idea for a script. In the last big scene, my lead character is photographing a movie set at the foot of the Eiffel Tower. Meanwhile, my other story line is winding up on top of the tower.” Noah Baumbach and Jake Paltrow leaned in over their kale salads at Gotham Bar and Grill. De Palma, bearded and bulky at seventy-five, wore a safari jacket, as befits a Hollywood director; his clean-shaven, slimmer, much younger friends from the indie world bracketed him in navy suits. De Palma went on, “So I asked myself, ‘What movie could be shooting at the foot of the Eiffel Tower?’ And I said, ‘Vertigo’!”Everyone grinned; the Hitchcock classic had left a heavy impress on such De Palma films as “Body Double” and “Dressed to Kill.” He went on, “ ‘Vertigo’ was originally a French novel, so I have to read it and figure out how, in the French version, did they kill the wife?”

On Thursday nights, the three directors, often joined by Wes Anderson, meet for dinner here or at Bar Pitti. One week in 2010, Baumbach and Paltrow filmed De Palma to preserve his stories for posterity. Over the years, they shaped their home movies into a documentary, “De Palma,” which just opened. Then they all went back to meeting simply to talk shop.

De Palma mentioned two enduring sources of chagrin: getting shot in the leg by the cops for hot-wiring a motor scooter when he was twenty, and casting the bronzed, wooden Cliff Robertson in “Obsession” in order to get the film made. (“That ridiculous tan!”) Then Paltrow threw out an idea: “How about a surveyor? Someone buries treasure as he’s watching through his lenses. That could be a De Palma.” De Palma chuckled noncommittally. Baumbach said, “Sometimes we come up with our concept of a De Palma movie and see if De Palma likes it.”

“We’re batting in the low .120s,” Paltrow said.

But De Palma said that their selection of clips from his movies for the documentary—cat-footed tracking shots, women being slashed to bits, cascades of blood—proved that they understood his predilections. “Watching it was like when you die and everything . . .” he revolved his hand, film-reel style, to indicate his life flashing before his eyes.

-Asked about Greetings and Hi, Mom!, De Palma says, "There are many things about them which I wish I had more of in my later films. They have a kind of spontaneity and life to them, because they're so rough, they're almost like sketches... I got very interested in developing a kind of a technique, and I went through about six films like that. Now I'm sort of moving back in the other direction, but I got very concerned with construction for many films. And sort of visualizations of stories and things like that. And I sort of got away from all this nutty, insane comedy that I used to do."

-Cavett: Who conceived the idea of a play in which the black cast attacked and raped members of the audience?

De Palma: I did. And I did it because there was a play I saw at the Public Theatre in which a black actor came out and assaulted the audience-- [starts pointing and mimicking] "You know what?!? [Scorsese is dying of inaudible laughter now] You're no good! You're no-- get out of here!!" And I see all these white people in front are going, [mimics sitting back and nodding in strong approval] "Yeah..." I couldn't believe this. [Scorsese continues to laugh, trying to control himself] We're sitting there being assaulted, abused, spit on, and they just said, "That's right! They're right!" You know, "We're no good-- right!" You know... they loved it!

Cavett: So you took the logical extension of that...

De Palma: No, it was, you know, big time of... Buck White, the year of those plays, where they just completely insulted the audience, and they just thought it was terrific.

-There is discussion about the different approaches/attitudes between De Palma and Scorsese regarding the types of films they each do. De Palma mentions that he has to have great (strong) actors, because his character scenes are so short/scarce, as compared to Scorsese, who explores scenes and dialogue with his actors, take after take. At one point, De Palma talks about the early cut he'd seen of New York, New York, saying it was "unbelievable at four and a half hours. Incredible." When asked by Cavett how so, De Palma continues, "Because, what's so fascinating about Marty is he takes all the variations on a theme in a scene and plays them all out. I mean that pick-up scene [to Scorsese], how long was that in the rough cut? [Scorsese says it was almost an hour] It was an hour long. The pick-up scene in the beginning of the movie, it was an hour long. And you can't believe it, it's like a ballet dancer jumping-- you can't believe they're going any higher. You know, he goes up, and up, and up, and up. [Whistles]"

The three amigos appeared on the June 10, 2016 episode of Charlie Rose (click the link to watch the video). A full transcript of the episode is available on the video link, as well. Here's the best bit:

The three amigos appeared on the June 10, 2016 episode of Charlie Rose (click the link to watch the video). A full transcript of the episode is available on the video link, as well. Here's the best bit:19:20 Charlie Rose: Dream sequences.

19:23 Brian De Palma: I like dream sequences because I do a lot of dreaming, and I'm trying to make sense of them.19:29 Charlie Rose: Do you really?

19:30 Brian De Palma: Yeah.

19:31 Charlie Rose: Well, but do you hire people to interpret your dreams?

19:34 Brian De Palma: No. But I get a lot of ideas from my dreams.

19:37 Charlie Rose: Do you really?

19:38 Brian De Palma: Yeah. If you go-- I don't know if this works for any of you guys, but if you're dealing with a problem and you go to sleep, somehow you work it out in your dream and you wake up and you're, ah-ha, that's it.

19:50 Charlie Rose: Does that happen to you?

19:53 Noah Baumbach: Yeah, versions of it. I don't put it in my movies.

19:58 Brian De Palma: Yeah, plus it's very stylized and you can do really crazy things.