AND WE HAVE SOMETHING SPECIAL: ALFONSO GOMEZ-REJON ON DE PALMA, HIS "CINEMATIC HERO"

Our host site, Lycos, was down for three days due to some kind of major data transfer that took longer than they expected. We'll get back on track this weekend with the documentary and related roundups, but first, something kind of special: yesterday, The Hollywood Reporter posted a guest column from director Alfonso Gomez-Rejon (several episodes of American Horror Story, feature film Me and Earl and the Dying Girl), titled "Why Brian De Palma Is My Cinematic Hero." Gomez-Rejon's column opens with him fighting with his producers to keep all of his split-diopter shots in an unnamed early film (which may or may not have been his remake of The Town That Dreaded Sundown). "I did my best to explain the power and psychological effect of a split diopter," he writes. "The paranoia I was trying to convey in this particular scene. How the entire film was an homage to the movies. How a film had defined a town and fictionalized it’s pain -- how those particular shots were an homage to my hero, Brian De Palma, and Blow Out, specifically. You can’t approach a split diopter shot intellectually; it’s a feeling."

Definitely go to the link above and read the entire column-- here's an excerpt:

Filmmaking has been my obsession since growing up in Laredo, Texas. I woke up thinking about movies. I fell asleep at night watching them. For me, De Palma was the apostle of cinematic technique. Delivering his sermons through the VHS tapes in my video store church. Pointing me in the direction of my own projection light. Bridging the gap between my cinematic fantasies and cinematic reality. This is how I watched Carrie, Dressed to Kill, Scarface and Body Double. De Palma’s camera was a character; he embraced it -- these were works of art that were defining the medium and moving it forward. He was breaking and reinterpreting the form. There was constant strategic and spectacular movement. There was color, sexuality, absurdity. He was literally directing you, telling you where to see. Everything seemed to be at the service of the movie. The images were alive. Iconoclastic works of energy that inspired cinematic curiosity. This first film of his that I watched in the theater was The Untouchables. I was 14 or 15 and went back with my father half a dozen times. I found myself mesmerized by the production design, the lighting, the score -- the great spectacle. Another monolith arose from the ground and I realized that cinema was also a collaborative enterprise.My first week at NYU in the fall of 1990, while walking in the Village, I saw Brian De Palma walking on the opposite side the street. We were on Sixth Avenue. He turned on to 8th Street towards Fifth Avenue. And I did the natural thing: I followed. There he was, walking like a regular person. Propelling himself forward, one foot in front of the other, like any other mortal. Movies stars always looking smaller in the flesh, but De Palma was even bigger. I felt like a small-time mobster casing a target, or a De Palma steadicam shot. This was my secret, privileged moment.

Here was the man who taught me about storyboarding in a Premiere Magazine article that published his early Macintosh boards for Casualties of War. He opened me up to the actual craft. The engineering. The planning -- skills that would later lead to a tiny career of me boarding my way through college for extra money, working on independent and graduate thesis films.

Once in New York, I practically lived at Bobst Library, going through their video library, discovering films my local video store didn’t carry. Dionysus in '69, Sisters, The Fury, Blow Out and Phantom of the Paradise. And then, of course more Hitchcock -- and then there it was, De Palma’s playful relationship with the past and nod to the masters that shaped him. Studio films with a Hollywood scope that defied and maybe even played the system. He was exploring the past but remaining a trailblazer that energized me in the present. Although I was an intensely shy kid, I found myself in full-on attack mode when a classmate would dismiss one of his films. The Untouchables and Scarface could never be contested. But if someone would dismiss Blow Out, I’d pounce. There was an innate sense that I needed to protect the masters and their extraordinary vision, especially those who I felt were under-appreciated. It was my duty.

A couple of years later, he was shooting Carlito’s Way down the street from my dorm in the West Village. They were working nights and I would just watch from the sidewalk -- as close as a PA would let me get. Pacino. De Palma and Stephen Burum. Fake rain. The biggest set I had ever seen. It was quite literally the realization of my dreams; an extraordinary sensation that overwhelmed me and cemented that I had chosen the right career ... however long and however painful that journey might be. This search for an identity that had always plagued me because of the nature of where I was from, went away. I only needed to be defined by my dreams and hopefully, resilience, not unlike what -- from the outside -- De Palma has shown throughout his career.

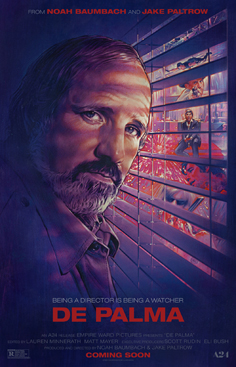

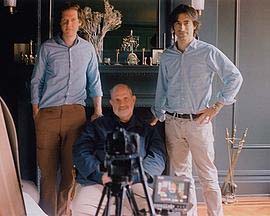

Not to present a sort of "point/counterpoint," but the articles about the new documentary De Palma by

Not to present a sort of "point/counterpoint," but the articles about the new documentary De Palma by

Go to

Go to