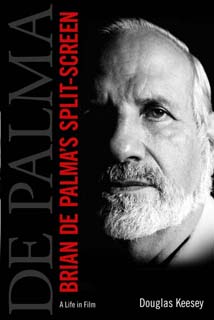

'BRIAN DE PALMA'S SPLIT-SCREEN: A LIFE IN FILM'

On Monday, The Washington Post's Dennis Drabelle posted a review of Douglas Keesey's recent book, Brian De Palma's Split-Screen: A Life In Film. Here are some excerpts:

On Monday, The Washington Post's Dennis Drabelle posted a review of Douglas Keesey's recent book, Brian De Palma's Split-Screen: A Life In Film. Here are some excerpts:Keesey has taken an unusual approach to his subject. Rather than lay down a biographical foundation at the outset, he introduces elements of De Palma’s private life as they crop up in his movies: 29 in all, which Keesey summarizes and analyzes in chronological order. (To avoid plot spoilage, save Keesey’s chapter on a given film until after you’ve seen it.) This works better than one might expect because, more than most directors, De Palma pours his psyche into his work. “When you’re making a movie,” he has said, “you think about it all the time — you’re dreaming about it, you wake up with ideas in the middle of the night — until you actually . . . shoot it. You have these ideas that are banging around in your head, but once you objectify them and lock them into a photograph or cinema sequence, then . . . they no longer haunt you.” De Palma has also written the scripts for many of his films, but Keesey could have done a better job of helping us keep track of who did what. The book cries out for a filmography.As it turns out, De Palma has a highly charged past to draw on. When he was in his late teens, his father, an orthopedic surgeon in Philadelphia, allowed the boy to watch him in action. “I was standing right next to him in front of the operating room table,” De Palma recalled of one episode. “He cut off a patient’s leg and then gave it to me!” When Dr. De Palma had an extramarital affair, Brian found out about it, sided with his mother and got busy gathering evidence on her behalf with a tape recorder and a camera. And for all his eventual success, Brian was not the standout among the offspring. That honor went to his mathematically gifted older brother Bruce, with whom Brian had to compete as a kid. (Bruce later descended into what Keesey calls “a kind of hubristic madness.”)

De Palma works out that sibling rivalry in Sisters, in which the eponymous women — both played by Margot Kidder — were born as conjoined twins and then surgically separated. De Palma’s harrowing experience in that operating room helps account for the dismemberment in Body Double. As for using a tape recorder to gather incriminating evidence, look no further than Blow Out...

One more thing about Blow Out. Although it obviously owes something to Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up (as even the titles suggest) and Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation, I think Blow Out outclasses both forerunners in sheer entertainment value. In any case, that seems to be the way with De Palma: He is one of those artists whose forte is spinning variations on themes pioneered by others. And what’s wrong with that? What contemporary mystery writer hasn’t been strongly influenced, at least indirectly, by Wilkie Collins and James M. Cain? What writer of romances doesn’t owe a big debt to the Brontë sisters and Daphne du Maurier?

Hollywood has shamefully neglected De Palma; he’s never even been nominated for a best director Oscar. Brian De Palma’s Split-Screen announces that it’s time for a reassessment of his unjustly slighted oeuvre.

Now that

Now that

Sorry I missed this, but two days ago,

Sorry I missed this, but two days ago,

Late this afternoon,

Late this afternoon,