GREETINGS LINKED TO STRANGLERS

AND NEW ESSAY COVERS GREETINGS/HI, MOM!/RABBIT

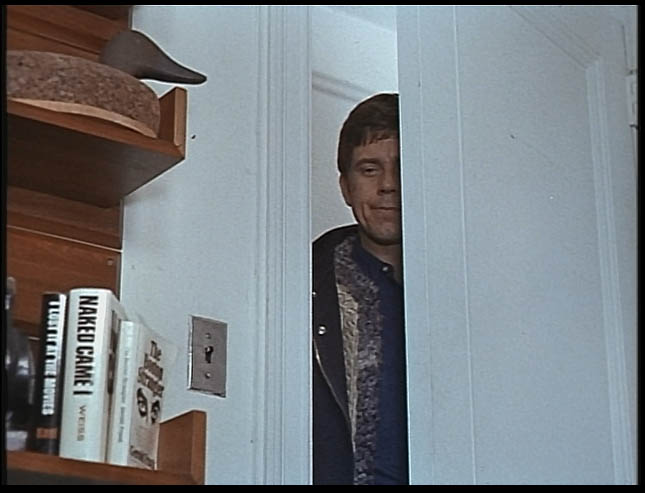

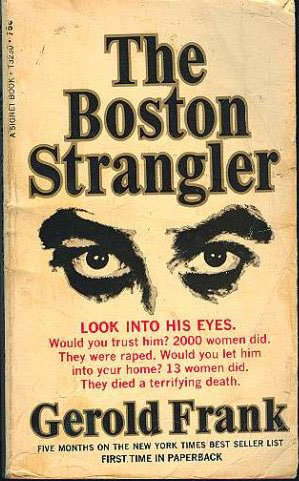

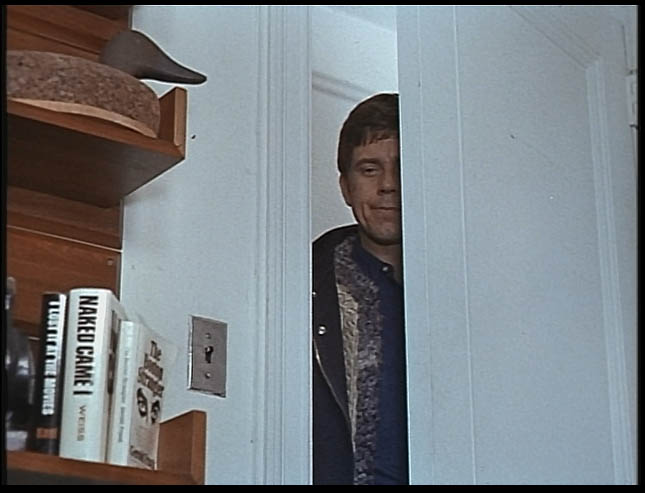

After reading David Greven's terrific new essay on male bonding in Brian De Palma's Greetings, Hi, Mom!, and Get To Know Your Rabbit (published in the current issue of Genders), I noticed that Greven somehow had seemed to overlook a key plot point in Greetings that I would love to see him riff on (more on that later). Curious, I pulled out my DVD of the film to check on said plot point, and discovered something rather astonishing-- namely The Boston Strangler, paperback edition of the Gerold Frank true crime book, dead center in the frame from Greetings as shown above. Astonishing, of course, because De Palma is currently preparing to film Susan Kelly's more recent investigation of the case as presented in her book, The Boston Stranglers, and because I don't recall noticing this title in Greetings before. However, you can bet that De Palma did-- check out the countershot below:

Note some key differences between the two reverse shots, beginning with the way the three books are angled in the second shot, so that the viewer can clearly see the cover of The Boston Strangler. Also notice how in the first shot, there appears to be a long row filled with books behind Strangler, while in the reverse shot, there are only three key books and what looks like a glass jar to the left of those. Keeping in mind that De Palma edited as well as directed Greetings with a decidedly loose, freewheeling style, the lack of proper continuity in the shots echoes the purposely off-kilter jump-cuts used in various scenes throughout the film (Greven's essay delves into one of these scenes, where a patron in a clothing store switches places back-and-forth with the store's proprieter via these sort of surreal jump-cuts). Frank's account of the Boston Strangler case was first published in 1966, two years before Greetings was released. Richard Fleischer's film, based on Frank's book and starring Tony Curtis and Henry Fonda (and featuring plenty of split-screens), was released a mere two months prior to Greetings.

One can guess that the Boston Strangler case was still a fairly frenzied affair in 1968. Placing that book square in the center on the big screen, next to a naked woman who has left her bedroom door open, allowing total access to a man she's only just met through a computer dating service, must have been a howl of a joke in the movie theater in 1968 (especially with the film version about to hit screens). It would have been key to the joke to have the book still noticeable from the front cover in the reverse shot, as Paul (Jonathan Warden) looks in, gazes upon the woman's naked body, smiles and then decides not to bother with her. In the second shot above, De Palma has placed two other key books on the shelf: Naked Came I, which directly comments on the scene at hand, in which the woman, who has just berated Paul for not being prepared for anything other than sex, retreats to her bedroom and humbles (compromises) herself by taking off all of her clothes and lying in wait (the book's title indirectly echoes the Book of Job, which would figure prominently in De Palma's Mission: Impossible when Ethan Hunt pulls the Holy Bible off the book shelf);  and, among the many film-themed books and magazines diligently placed throughout Greetings, I Lost It At The Movies, the first collection of film reviews by Pauline Kael (in the shot at right is another key film book placement within Greetings).

and, among the many film-themed books and magazines diligently placed throughout Greetings, I Lost It At The Movies, the first collection of film reviews by Pauline Kael (in the shot at right is another key film book placement within Greetings).

So on to the plot point that led me to rewatch this sequence in the first place, which appears to have gone overlooked in paragraph #38, below, of Greven's essay (I have emphasized two key phrases in bold):

At one point, Paul goes to the home of a woman with whom he has a computer-dating-arranged assignation. During their conversation, he reveals that he doesn't own a car and that he's already eaten; he makes it clearly obvious that he is only there for sex. Brassy and demanding, she upbraids him for being ill-prepared for their date. Like a general describing the battle-readiness of his troops, she points to specific elements of her romantic-evening-ready attire: "You see these shoes? 'Socialites'!" He wilts visibly under the glare of her scorn. She storms off. Yet when Paul goes to check in on her, she is lying in her bed, silent, naked. He walks off, and away. More than any other, a profound sense of loneliness, of a lack of connection, permeates this scene. This sense of cold isolation also tinges the scene in which Lloyd, feverishly pontificating over the JFK assassination and his multiple conspiracy theories, uses the silent, naked body of the woman he is in bed with as a living canvas, turning her over, and back again, drawing strategic sites of the grassy knoll upon her body. Like a cadaver, her body mutely complies with his feverish demands and doodling. The necrophiliac quality of this scene provides further evidence for the lack of relatedness between men and women, even in a scene that establishes physical intimacy between them. (The necrophilia here is too half-hearted to vie for the status of perversity.)

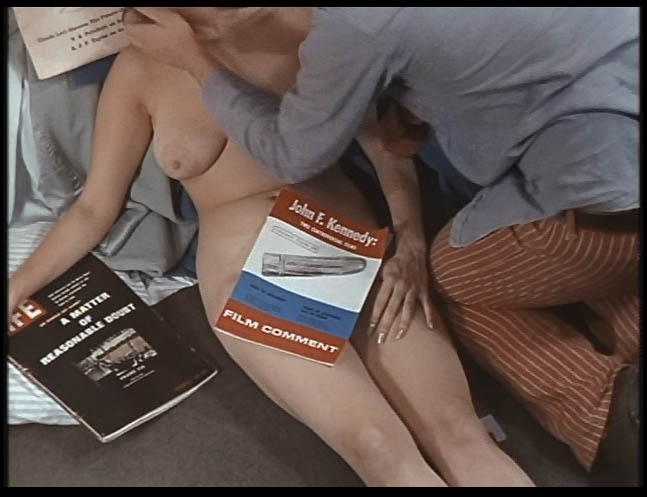

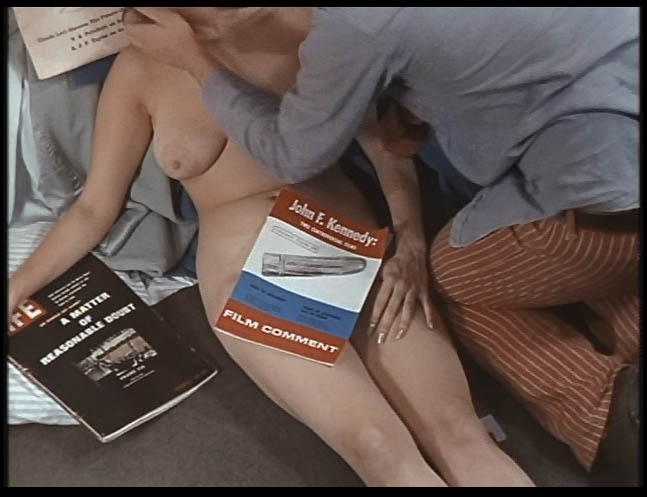

What Greven seems to have overlooked is that it is the same woman in each scenario he describes above-- Paul leaves the woman lying naked on the bed, and goes outside to call Lloyd from a payphone. Paul tells Lloyd that his computer date did not seem like a good match for him, but that "since you're one of my best friends," maybe she would be a good match for Lloyd. The film then cuts to a shot of another strategically placed piece of literature: the cover of Film Comment...

The camera slowly pulls back to reveal the film magazine, with its cover story about the JFK assassination, covering the pelvis of the woman as Lloyd can be seen manipulating her stiff, motionless, and otherwise naked body. A viewer (especially one watching in 1968) might at first imagine that a Boston Strangler type of situation is in process here as the camera pulls back and sees that the potential strangler has been replaced by Lloyd's JFK obsessions. But instead of a lifeless corpse, we eventually find that the woman is merely sleeping, apparently having already been sexually satisfied (in her slumber, when Lloyd needs her to turn around to put a shirt on her, he kisses her once or twice on the neck until she dozingly complies). What is implicit in this sequence of scenes is that Paul has left the woman in her apartment, and allowed his friend Lloyd to take over (did Lloyd have to knock, or did Paul leave the door unlocked?). What makes it a key point for Greven's highly insightful essay is that it may further complicate his central questions of male bonding and the treatment of women within the homosocial sphere.

I have a couple more things to post about Greetings-- watch for two more posts this weekend...

Cult star Brinke Stevens, credited as "Girl #3 in Bathroom" in Brian De Palma's Body Double (1984), was asked by Fangoria's Sean Abley about "the weirdest film, TV show or commercial from which you still earn residuals"-- Stevens' reply:

Cult star Brinke Stevens, credited as "Girl #3 in Bathroom" in Brian De Palma's Body Double (1984), was asked by Fangoria's Sean Abley about "the weirdest film, TV show or commercial from which you still earn residuals"-- Stevens' reply: Abley then tells Stevens, "OK, my friend, actor Michael Kearns, had the exact same story about BODY DOUBLE! He sat around for a week, then had three lines or something and continues to make bank from it! Nice."

Abley then tells Stevens, "OK, my friend, actor Michael Kearns, had the exact same story about BODY DOUBLE! He sat around for a week, then had three lines or something and continues to make bank from it! Nice."

Brian De Palma will narrate at least one episode (maybe two-- see below) about his own films as part of

Brian De Palma will narrate at least one episode (maybe two-- see below) about his own films as part of  After 29 to 30 hours of deliberations, a Los Angeles Superior Court jury this afternoon announced their verdict, and Phil Spector was convicted of second-degree murder in the death of Lana Clarkson, who was shot in the mouth at Spector's mansion after meeting him hours earlier while working her job as a nightclub hostess. According to

After 29 to 30 hours of deliberations, a Los Angeles Superior Court jury this afternoon announced their verdict, and Phil Spector was convicted of second-degree murder in the death of Lana Clarkson, who was shot in the mouth at Spector's mansion after meeting him hours earlier while working her job as a nightclub hostess. According to  Michael Caine discussed some of his film roles in an article published yesterday in the

Michael Caine discussed some of his film roles in an article published yesterday in the  Armond White on Fast & Furious in the

Armond White on Fast & Furious in the

The artist in the scene mentioned above (and in the Greetings shot above) is Richard Hamilton, who is considered one of the fathers of the "pop art" movement (a movement that is satirized in Greetings when Robert De Niro's Jon labels his voyeuristic project "peep art"). At left is the piece Hamilton is showing to Gerrit Graham's Lloyd, titled

The artist in the scene mentioned above (and in the Greetings shot above) is Richard Hamilton, who is considered one of the fathers of the "pop art" movement (a movement that is satirized in Greetings when Robert De Niro's Jon labels his voyeuristic project "peep art"). At left is the piece Hamilton is showing to Gerrit Graham's Lloyd, titled  This is the full cover of the bestseller

This is the full cover of the bestseller

and, among the many film-themed books and magazines diligently placed throughout Greetings, I Lost It At The Movies, the first collection of film reviews by Pauline Kael (in the shot at right is another key film book placement within Greetings).

and, among the many film-themed books and magazines diligently placed throughout Greetings, I Lost It At The Movies, the first collection of film reviews by Pauline Kael (in the shot at right is another key film book placement within Greetings).

In an article in yesterday's

In an article in yesterday's