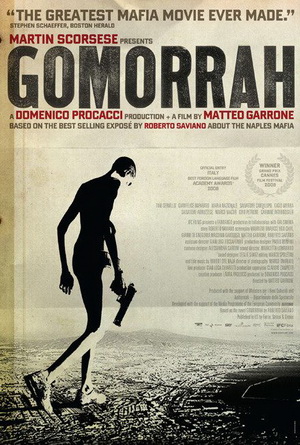

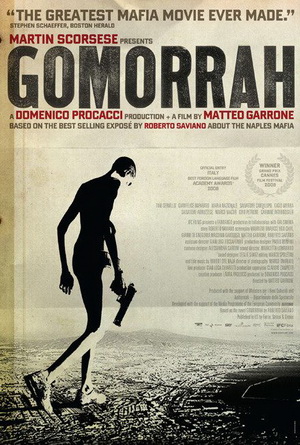

GOMORRAH & SCARFACE

BOOK & FILM SHOW INFLUENCE OF GANGSTER FILMS

Every review of

Matteo Garrone's

Gomorrah mentions

Brian De Palma's

Scarface, and for solid reasons: two characters in the film go around Naples acting out scenes from

Scarface. The film is based on the book of the same name by

Roberto Saviano, who has been under 24-hour armed protection since 2006, when his book, which peers unblinkingly into the Camorra Mafia, became a bestseller and the author was besieged by death threats. Fellow author

Salmon Rushdie, who was famously condemned to death by

Ayatollah Khomeini in 1989 and went into hiding when his novel,

The Satanic Verses, was deemed by Khomeini as insulting to Islam,

told reporters in Rome last October that Saviano is in even greater danger than Rushdie had been, because the reach of the Camorra is incredibly expansive.

In Saviano's book, he spends some time delving into the relationship between the Comorra and Hollywood, finding that it is not Hollywood reflecting reality, but the other way around. Here is an excerpt in which Saviano walks through the former mansion of one Mafia boss who had given his architect a copy of De Palma's Scarface because he wanted Tony Montana's villa, "exactly as it was in the movie," a villa, Saviano states, that everyone calls Hollywood. However, after being caught by the police, the boss had everything removed because, as Saviano writes, "If he couldn't use it, it shouldn't exist. Either his or no one's"...

He had the doors taken off their hinges, the windows removed, the parquet taken up, the marble pulled off the stairs, the expensive fireplace mantels disassembled. Ceramic bathroom fixtures, wood railings, light fixtures, and kitchen appliances were removed, and antique furniture, china closets, and paintings carried off. He gave orders to strew the house with tires and set them on fire, ruining the plaster and damaging the columns. Even so, he managed to leave a message. The only thing left untouched was a bathtub, sitting on three wide steps in the living room. A princely version, with a lion's face that roared water. The boss's great indulgence. The tub sat right in front of a Palladian window that looked directly onto the garden. A sign of his power as builder and Camorrista, like an artist who cancels out his painting but leaves his signature on the canvas. As I wandered through those blackened rooms, I felt my chest swell, as if my insides had become one giant heart. It beat harder and harder, pumping through my entire body. My mouth had gone dry from the deep breaths I took to calm my anxiety. If some clan sentinel had jumped me and beaten me to a pulp, I could have squealed like a butchered pig but no one would have heard me. Evidently no one saw me enter, or maybe no one was guarding the villa anymore. A pulsating rage rose up inside me. Flashing in my mind, like a giant swirl of fragmented visions, were the images of friends who had emigrated, joined the clan or the military, the lazy afternoons in these desert lands, the lack of everything except deals, politicians mopped up by corruption, and empires built in the north of Italy and half of Europe, leaving behind nothing but trash and toxins. I needed to vent, to take it out on someone. I couldn't resist. I stood on the edge of the tub and took a piss. An idiotic gesture, but as my bladder emptied, I felt better. That villa was the confirmation of a cliché, the concrete realization of a rumor. I had the absurd sensation that Tony Montana was about to come out of one of the rooms and greet me with a stiff, arrogant gesture: "All I have in this world is my balls and my word, and I don;t break them for no one, you understand?" Who knows if Walter dreamed of dying like Montana too, riddled with bullets and tumbling into his front hall rather than ending his days in a prison cell, consumed by Graves' disease, his eyes rotting and his blood pressure exploding.

Saviano goes on in this chapter to relate how the movies are studied by generations of bosses and criminals who want to carve out an image for themselves. The author provides examples of these from several films, including The Godfather ("Before the film came out," writes Saviano, "no one in the Sicilian or Campania criminal organizations had ever used the term padrino"), Il camorrista ("The film's sound track has become a sort of Camorra theme song, whistled when a neighborhood capo walks by, or just to make a shopkeeper nervous"), Good Fellas (Saviano imagines one scene flashing in a would-be gangster's mind as he meets his death), The Crow (one man wore clothes reminiscent of Brandon Lee's in that film), Pulp Fiction (Camorra killers have started holding their guns crooked, the way they do in Tarantino's film, which makes them horrible shooters for which they compensate by leaving a bloody mess everywhere), Kill Bill (bodyguards for female bosses dress like Uma Thurman's character), Nikita (one woman's nickname), and even Taxi Driver (two young bullies would start fights with a look, and then repeat after Robert De Niro's famous lines from that film: "You talkin' to me?").

Those two bullies are the characters in the film mentioned at the top of this post. In early January, it was announced that Martin Scorsese would lend his name in support of IFC Films' U.S. release of Garrone's Gomorrah, which opened in select U.S. theaters this past weekend. "Matteo Garrone's Gomorrah is a tough, forceful look at the Neapolitan underworld," Scorsese told the Hollywood Reporter. "I admire the bluntness of this picture and the devotion of Garrone and his actors in their pursuit of a terrible truth. Gomorrah is despairing, but it's also enlightening and, because of its frankness, strangely heartening." Garrone responded, "I have been waiting for some time for the chance to thank Martin Scorsese publicly for the courage and generosity he has shown in laying his support on the line for Gomorrah. I can't forget how deeply touched I was seeing him arrive for the presentation of the film; of all directors, he is one of the most important in my development as a filmmaker. I am therefore extremely proud that the film has found such a prestigious adoptive father, and I will certainly cherish this memory for all time."

GOMORRAH REVIEWS

GOMORRAH REVIEWS

What follows are links to several reviews of Garrone's film, with selected excerpts:

Anthony Lane at the New Yorker

There is a pair of teen-agers, Marco (Marco Macor) and Ciro (Ciro Petrone), fools in love with a gangsterish ideal; “I’m No. 1! Tony Montana!” they cry, acting out their pantomime of Scarface in an empty tenement, where a sunken, unused bath echoes not just old Brian De Palma movies but much older tubs, in the balneae of Pompeii, across the bay... Garrone’s film is less furious than Saviano’s book, which has the tang of personal nausea, and for that reason, I suspect, it will prove more enduring. (It failed to make the nominations for Best Foreign Film at the Academy Awards: the usual travesty.) As I watched various Scampians being slain or spared on a whim, I felt borne along not so much by reportage, however well dramatized, as by a fierce meditation on the vagaries of fate—and thus, oddly enough, by the pull of comedy. When Franco, in a cathedral-size quarry, needs a new set of truck drivers to shift his drums of corrosive chemicals, whom does he call? Local children, who perch on cushions to see through the windshield; in a way, they make better mafiosi than the adults, yielding with less caution and complaint to their instinctual urges. There is a terrible numbness to the grownups, spun in the endless cycle of revenge; “We don’t know anything” is the conclusion of one group, which agrees to press ahead with murder, for want of another plan. I’m not sure that, after this movie, I will be able to take quite such unquestioning pleasure in the suave, all-knowing dons of the Godfather trilogy, let alone the stylized brutality of Scarface; the spoiled earth of Gomorrah is the ground zero of Mob cinema, burning away the sleekness and self-congratulation of the genre.

Armond White at the New York Press

Director Matteo Garrone pretends to expose Camorra, the vicious Neapolitan version of the Mafia that has ravaged contemporary Italian society. His title’s clever reference to Sodom and Gomorrah decadence implies biblical judgment. But Gomorrah’s five interlocking stories are told with slow, almost obscenely casual regard. Garment worker Pasquale (Salvatore Cantalupo) tries to outfox the mob; Gaetano (Vincenzo Altamura) double-crosses a gang; young thugs Sweet Pea and Pitbull (Salvatore Ruocco and Vincenzo Fabricino) embark on a mini-war against townspeople while defying veteran hoods; and teenage delivery-boy Toto (Salvatore Abruzzese) chooses dangerous role models. Garrone’s mix of local color, environmental anarchy and sensationalism is prurient; Gomorrah always heads toward awful, inevitable moments of deception and vengeance. In the Godfather films, Coppola’s revelations of our deepest thoughts about law, order and human weakness were enthralling. That’s why the three-thousand gangster movies The Godfather inspired don’t measure up—and why Coppola’s trilogy still feels definitive.

Chuck Williamson at Out 1 Film Journal

While it did not “reinvent the wheel” of contemporary gangster cinema, Brian De Palma’s Scarface nonetheless underlined in thick, bold strokes the genre’s internal frictions and contradictions. Scarface amplified the genre’s basest elements, reimagining its narrative as a sensationalistic, overstuffed, Grand Guignol cartoon that forced audiences to confront, up front and personal, the paradox implicit within all mob movies: the glamorization of the gangster. Because of its lack of nuance and subtlety, De Palma’s film made those once inconspicuous contradictions more explicit. Scarface, like most gangster films, turned its antagonist into an icon of cool, a two-fisted merchant of death with both charisma and cojones—and no amount of anti-crime moralizing could cancel out the intrinsic allure of such a character. For all the bullet wounds and moralizing of its “crime doesn’t pay” third act, the film largely functions as a male adolescent fantasy, a fever dream concoction where decadent materialism is rewarded, macho posturing leads to steamy sex (with nudity!), enemies are mowed down in satisfying spurts of splatter-gore, and men speak in expletive-laced bon mots like, “This town is a great big pussy just waiting to get fucked.” Loaded with both implicit and explicit references to Scarface, Matteo Garrone’s Gomorra reappropriates the pop-culture image of gangster cool and makes visible its seams, cracks, and inherent hollowness.

In its most memorable scene, two skinny, anemic-looking teenagers—Marco and Ciro—strip down to their underwear, stroll through a riverbank, and crudely reenact Scarface’s final shoot-out sequence with a pair of stolen semi-automatic weapons. “You sounded just like Tony Montana,” one says to the other, but nothing could be further from the truth. Using Scarface as a “how-to” manual, these two boys may have memorized the film’s macho swagger and f-bomb sloganeering, but their ritual still comes across as a children’s game, a media-constructed façade that fails to mask the authentic image of two vulnerable, naked youths. They are pathetic, juvenile, a pair of children pretending to be big, bad gangsters—and despite their reprehensibility, they remain somewhat sympathetic, as they have bought into the false constructs of Hollywood and will, of course, pay the consequences. While the scene could be described as both self-reflexive and revisionist, it also carries an undercurrent of tragedy, as their inevitable (and bloody) downfall seems designed right from the first pull of a trigger.

R. Kurt Osenlund at Your Movie Buddy

Gomorrah redefines the mob flick because it shows a criminal association not as it might be, but as it is. Still, Garrone isn't above giving a nod to his genre predecessors, namely Brian De Palma and his immortal Pacino vehicle, Scarface. The brief opening sequence has a tacky neon opulence reminiscent of the cult classic – even the title logo goes from red to “Vice City” pink – and, later, the delinquent duo play with empty pistols in an empty warehouse and pretend to be Tony Montana. What would Tony say if he saw Gomorrah? Fuhgeddaboutit? No way. Not this merciless movie. It sticks with you for days.

Christy Lemire at Associated Press

Two cocky Italian teenagers run around their dilapidated Naples neighborhood, melodramatically riffing on Scarface lines to each other: "Now it has to be ours, the whole world. Miami, all of it." They're certainly no more over-the-top than Al Pacino. But this is the closest director and co-writer Matteo Garrone comes to any sort of traditional, Hollywoodized depiction of mob life in Gomorrah.

It's appropriate, though, that Brian De Palma's bloody epic is the source of inspiration for wannabe thugs Marco (Marco Macor) and Ciro (Ciro Petrone). That film, and the genre in general, are so entrenched in contemporary pop culture that they've become a source of self-parody.

That's what's so compelling about Gomorrah: It upends everything you think you know about the mob, and mob movies.

Steve Erickson at Gay City News

In a sense, Gomorrah is a humanist gangster film. It goes out of its way to avoid glamorizing the Mafia - among recent films, only Johnnie To's Election and Triad Election have presented a grimmer version of organized crime. Just to make sure we get the point, Gomorrah has two of its characters constantly quote dialogue from Brian De Palma's Scarface and compare themselves to its anti-hero, Tony Montana. No doubt they missed the memo that Scarface was intended as a critique of '80s excess and greed. Italian director Matteo Garrone clearly doesn't want anyone to make the same mistake with his film.

Ironically, despite its humanism, Gomorrah could hardly be more nihilistic. It veers among five different storylines. If the Mafia angle isn't immediately apparent in each one, it soon becomes clear. The screenplay never brings these narrative threads together; in a post-Paul Haggis climate, that's something for which we can be grateful. However, this is the kind of film where no one takes any moral stances until two hours have passed.

Greg Oguss at LA Snark

The Scarface references aren’t arguing the case that violent entertainment begets violent children or the truism about contemporary gangsters taking their cues from movie gangsters. Instead, they merely make an effective contrast between De Palma’s romantic vision and a milieu without any charismatic anti-heroes or blaze-of-glory deaths, where loyalties are never taken seriously enough to be betrayed. Even the few functionaries who walk away from the corrupt empire by the story’s end lack nobility, with their paths determined principally by cowardice and naiveté. Despite being well-versed in the bloody justice doled out by the mafia, the film’s myopic characters have little understanding of how completely the illegal and legal businesses of the Camorra shape their existence. Gomorrah’s end-titles offer a tally of official statistics to illustrate the Camorra’s social costs, suggesting that, by certain measures, this is the most criminally violent place on the planet. But the film offers no scenes of anti-mafia police efforts and the collective struggle required to change the region’s way of life is beyond the imagination.

J. Hoberman at the Village Voice

Martin Scorsese may be presenting Matteo Garrone's Gomorrah, but this corrosive, slapdash, grimly exciting exposé of organized crime in and around Naples comes on like Mean Streets cubed. Detailing daily life inside a criminal state, it's a new sort of gangster film for America to ponder...

In a vacant lot outside the fortress walls, two skinny teenagers play at being the antihero of Brian De Palma's Scarface. That's the fantasy; robbing African crack dealers is the reality, after which the two aspiring gangsters dance in scurvy triumph on some gray-sand beach. Their dreams come true when they stumble upon a cache of weapons, including AK-47s and a bazooka. Meanwhile, the Camorra expands into legitimate businesses, from garbage disposal to haute couture.

Garrone skips from one Camorra scam to another, all plots climaxing amid inexplicable internecine warfare in a more or less simultaneous reckoning. Gomorrah's episodic, mosaic structure is in some ways comparable to Steven Soderbergh's Traffic, but Garrone is not so much interested in diagramming a process as mapping a specific terrain. Despite its vivid characterizations, the movie stays on the surface—or, rather, it offers a sort of neorealist reportage. (Occasionally, the sober frenzy indulges in the sort of grotesque humor Garrone employed in his 2002 black comedy The Embalmer, wherein the Camorra enlists a professional taxidermist to stitch a shipment of drugs into a corpse.) The undistinguished visual style is predicated on a jittery wide-screen SteadiCam. There's a sense that Garrone's bobbing and weaving camera is just hanging with the homies—a strategy akin to Saviano's in his first-person book.

Saviano devotes an entire chapter to detailing the often-comic Camorrista fascination with Hollywood gangster flicks—mainly De Palma's Scarface, but also The Godfather, GoodFellas, and Pulp Fiction. "It's not the movie world that scans the criminal world for the most interesting behavior," he writes. "The exact opposite is true." Garrone has taken this to heart. Characterized as it is by a total absence of antiheroic glamour, his unsentimentally tough and unrelentingly squalid movie is unlikely to inspire much real-world imitation.

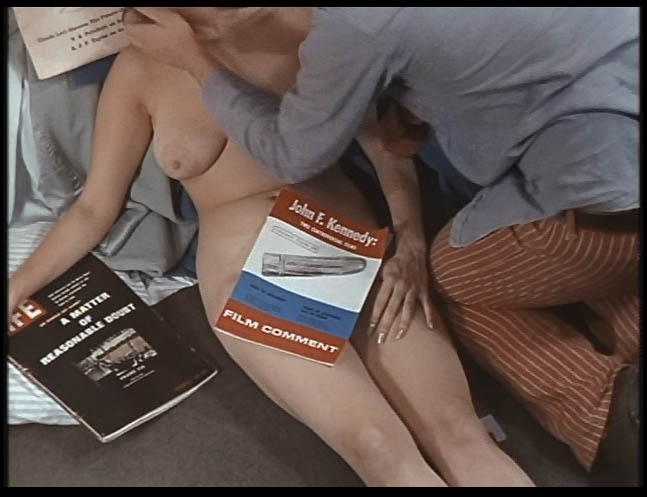

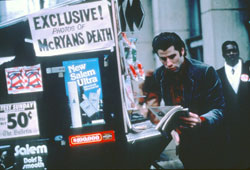

The artist in the scene mentioned above (and in the Greetings shot above) is Richard Hamilton, who is considered one of the fathers of the "pop art" movement (a movement that is satirized in Greetings when Robert De Niro's Jon labels his voyeuristic project "peep art"). At left is the piece Hamilton is showing to Gerrit Graham's Lloyd, titled "A Postal Card for Mother," in which a series of blow-ups of a beach scene are folded out accordion-like from the source photograph. The same year that Greetings was released, Hamilton designed the famous-iconic cover for the Beatles' "White Album," as well as the poster inserted inside the double-LP package, for which he asked for and was given hundreds of unpublished photos of the band to sort through.

The artist in the scene mentioned above (and in the Greetings shot above) is Richard Hamilton, who is considered one of the fathers of the "pop art" movement (a movement that is satirized in Greetings when Robert De Niro's Jon labels his voyeuristic project "peep art"). At left is the piece Hamilton is showing to Gerrit Graham's Lloyd, titled "A Postal Card for Mother," in which a series of blow-ups of a beach scene are folded out accordion-like from the source photograph. The same year that Greetings was released, Hamilton designed the famous-iconic cover for the Beatles' "White Album," as well as the poster inserted inside the double-LP package, for which he asked for and was given hundreds of unpublished photos of the band to sort through.

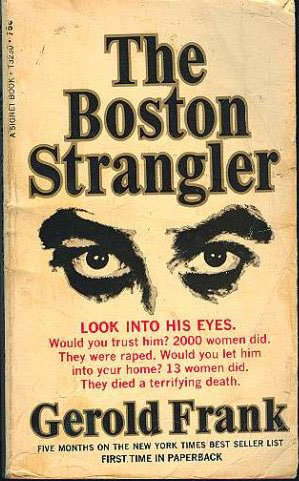

This is the full cover of the bestseller

This is the full cover of the bestseller

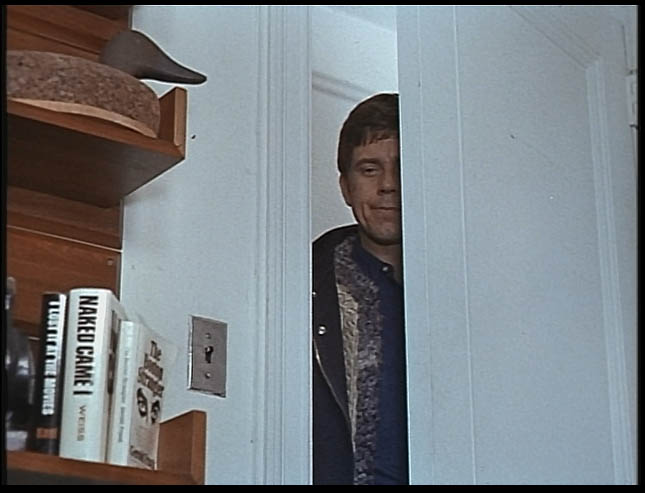

and, among the many film-themed books and magazines diligently placed throughout Greetings, I Lost It At The Movies, the first collection of film reviews by Pauline Kael (in the shot at right is another key film book placement within Greetings).

and, among the many film-themed books and magazines diligently placed throughout Greetings, I Lost It At The Movies, the first collection of film reviews by Pauline Kael (in the shot at right is another key film book placement within Greetings).

In an article in yesterday's

In an article in yesterday's  Today's

Today's  Exactly nine years ago today, Brian De Palma's Mission To Mars was released in theaters. It was the second time De Palma worked with actor Gary Sinise, who had appeared in De Palma's Snake Eyes just two years earlier. It doesn't look like the pair will be making any films together anytime soon.

Exactly nine years ago today, Brian De Palma's Mission To Mars was released in theaters. It was the second time De Palma worked with actor Gary Sinise, who had appeared in De Palma's Snake Eyes just two years earlier. It doesn't look like the pair will be making any films together anytime soon.  It's been a great week for writing about specific Brian De Palma films. First up, a most insightful piece about De Palma's latest, Redacted, from The Celluloid Liberation Front, courtesy

It's been a great week for writing about specific Brian De Palma films. First up, a most insightful piece about De Palma's latest, Redacted, from The Celluloid Liberation Front, courtesy  Next up, Drew McWeeny posted an essay Tuesday about De Palma's Blow Out as part of his

Next up, Drew McWeeny posted an essay Tuesday about De Palma's Blow Out as part of his  And just today, Scott Tobias posted a wonderful essay about De Palma's Femme Fatale as part of his weekly

And just today, Scott Tobias posted a wonderful essay about De Palma's Femme Fatale as part of his weekly  Every review of Matteo Garrone's Gomorrah mentions Brian De Palma's Scarface, and for solid reasons: two characters in the film go around Naples acting out scenes from Scarface. The film is based on the book of the same name by Roberto Saviano, who has been under 24-hour armed protection since 2006, when his book, which peers unblinkingly into the Camorra Mafia, became a bestseller and the author was besieged by death threats. Fellow author Salmon Rushdie, who was famously condemned to death by Ayatollah Khomeini in 1989 and went into hiding when his novel, The Satanic Verses, was deemed by Khomeini as insulting to Islam,

Every review of Matteo Garrone's Gomorrah mentions Brian De Palma's Scarface, and for solid reasons: two characters in the film go around Naples acting out scenes from Scarface. The film is based on the book of the same name by Roberto Saviano, who has been under 24-hour armed protection since 2006, when his book, which peers unblinkingly into the Camorra Mafia, became a bestseller and the author was besieged by death threats. Fellow author Salmon Rushdie, who was famously condemned to death by Ayatollah Khomeini in 1989 and went into hiding when his novel, The Satanic Verses, was deemed by Khomeini as insulting to Islam,  GOMORRAH REVIEWS

GOMORRAH REVIEWS