THE FILM WAS CHOSEN FOR DISCUSSION BY GUEST ARJUN HUNDAL - PODCAST HOSTED BY ERIC PEACOCK

Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | March 2023 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

| 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 |

| 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | |

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

Filmmaker: It’s interesting that Freddie seems to be getting away from the camera, yet is being tracked by it. I was wondering how you want to establish her relationship to the camera in the film.Chou: It’s totally something that we built into the film, the dance between the camera and the actress. That reflects the dynamic of the character, her constant refusal to be labeled. I decided not to use [over the] shoulder camera. I thought it would be a bit too tautological for filming an agitated character. On the contrary, [we filmed] still shots on her face, but also larger shots with a lot of people. The best example is when she is first meeting her biological family at dinner; there are seven people around the table and it’s like she’s surrounded by people, but it’s only still shots. Then suddenly you can feel [the agitation] because, 20 minutes before, you got to know the fire inside of her and now you can read in her eyes. Even though she doesn’t move, she looks clearly petrified, but something is boiling in her. And I found the tension between [the] stillness of the shots and [the] politeness of the setting reflects a relationship in a traditional Korean family and the boiling fire inside her.

When she feels pressured by people, she starts to become her own filmmaker: transforming other people in the room into extra actors and secondary roles, deciding places and remapping, like at the bar in the beginning. It’s interesting, because it’s someone in the new territory. She’s remapping the restaurant, deciding which people are going to sit and everything like that. She’s not in control in a place that she doesn’t know anything about, so here’s an attempt at taking control. Interestingly, the way of taking control is to create chaos. I was very inspired by Nadav Lapid’s Synonyms and Brian De Palma’s Carlito’s Way for that chaos.

Another scene that’s interesting is the scene where Freddie dances and I’m on the track. I can do this camera movement, the camera can pan a bit and I myself can do the zoom. But then at the same time, I don’t control what she’s actually doing, she’s doing whatever she wants. It becomes this struggle between the two of us.

Filmmaker: Your film has a really interesting relationship to music, in addition to choreography. You have the beginning club scene where it’s on that track and you’re watching Freddie dance. Then you have the other underground clubs and singing at her birthday, which is even more pumped up and fantastical in a way, and even more chaotic. Then you have the last moment where she’s at the piano and she’s completely alone.

Chou: There is an evolution where I play with the cultural identity of the music, as well. At the beginning, you will hear a lot of old vintage Korean songs that symbolize a past Freddie can feel from the texture of the song. You can feel it comes from the ’70s, but because she doesn’t speak the language, it already embodies a contradiction of knowing it’s from the past, but also having no idea what it is. It’s your past that you don’t know. I felt that the first time I went to Cambodia and listened to old Cambodian music.

In the second part, much more of the music is as if she had emancipated herself from her past and decided in some kind of extreme, positive gesture to say, “Hey, you reject me from Korea. I assure you I can be Korean, but I’m not having any link with my family whatsoever. I killed your heritage and now I’m a Korean girl with a Korean boyfriend, a drug fiend and everything.” So the music is very contemporary German techno music, also contemporary Korean electronic music that was composed for the film and shows her state of mind.

The third part is more silence, as if she needed less music. Because music for many is some kind of refuge, for her it is some kind of place that she can jump into and find comfort in when she feels too much pressure. And that’s basically the dancing scene in the first act, when the music is suddenly put on and she dances and there are no other characters in that shot. She dances as if she was inventing her own space, time and temporality. In the last part, there is less music, as if maybe she was ready to listen.

Filmmaker: As opposed to escaping.

Chou: The music becomes not only a refuge, but also a place to express feelings and sentiments when language doesn’t allow you to do it. At the very end, as you say, I think that it is something different. She is ready to be active. This journey may be full of loneliness—being totally alone with herself—so that she can start to feel it’s time to play her own melody.

Rich Eisen: In Carlito’s Way, Pachanga’s lines were originally written in phonetically spelled heavy-accented slang that offended some of the crew members of Latino descent, so the lines were rewritten in standard English, and you were directed to improve – uh, improvise some slang. Is that true or false on that film?Luis Guzman: Yeah, I improvised everything, and I improved everything. [Eisman laughs] And one of the lines that I did was, we were doing ADR, and Brian De Palma, who directed it, he said, ‘Can you say something here?’ And it’s like, it’s the scene where Carlito’s dying, you know, this is after he’s been shot by Benny Blanco, and I looked at him, and I dropped in the line, says, ‘It be’s that way sometimes.’ But that was a real thing that we used to say in the neighborhood, that the older guys would say. You know, if you complained about something, they would look at you, say [shaking his head], ‘It be’s that way.’ So, yeah. But you know…

Rich Eisman: That was improvised, from your upbringing, you brought it to the table.

Luis Guzman: Yeah, I did. I did. I did, that was Luis Guzman, courtesy of the great poet writer that I grew up with in the neighborhood named TC Garcia.

Rich Eisman: You got a good Pacino story for me?

Luis Guzman: A good Pacino story… Yeah, so one day, you know, we’re doing that scene when Viggo Mortensen rolls into the office? And so, I had to go from upstairs… well, no. I had… something, it was seeing that I was downstairs, the camera starts on me, and then Al’s in the office, he walks out, he’s coming down the stairs, I’m running up the stairs, and it’s total darkness. You can’t see anything. So, I think on the second take, so the first time, some guy walks by me, I made it up. Second time, the guy’s in my way. And I grab him and I push him to the side and said, ‘Get the hell out of my way, I gotta get up there!’ I did not realize that that was Al. [Eisman laughs] That was Al.

Made with the reflexive panache that would make most modern directors weep, De Palma’s second collaboration with Pacino proved to be a much more muted affair than their first. Carlito’s Way sees a reformed Puerto Rican gangster trying to keep things clean upon his release from prison, but his attempts to own a garish nightclub that’s an assault on the senses of sight and sound inevitably gets tied up with the nefarious deeds he wanted to avoid. Poor guy! There’s not much hope for him throughout the two-and-a-half-hour runtime, seeing as the opening shots show his dead body being carried away. It’s great seeing Pacino, the same year he won his Oscar, slum around as a noble ex-con building his life up from nothing.In terms of delirious performances, Pacino actually struggles to let his Hooah-ness shine, thanks to the dominating lifeforce that is Sean Penn as Carlito’s insecure, belligerent, coke-fiend best friend. When Pacino isn’t trying to calm down Penn’s sweaty turn, he has to fend off a scenery-chewing Viggo Mortensen (wired and wheelchair-riding in his one scene) and a luminescent John Leguizamo as the flashy wannabe bigtimer Benny Blanco (from the Bronx). And, like all good movies, Luis Guzmán is in the background somewhere. It’s understandable how straight Pacino plays it; even in a De Palma movie, there’s a limit on how many insane performances you can have before a movie bursts at the seams. And while Pacino hadn’t yet leaned fully into the shouty, eye-bulging indulgences that the ‘90s would represent for him, he did get to lead a classic dialogue-free De Palma suspense sequence, evading sinister characters across a big railway station. Little victories.

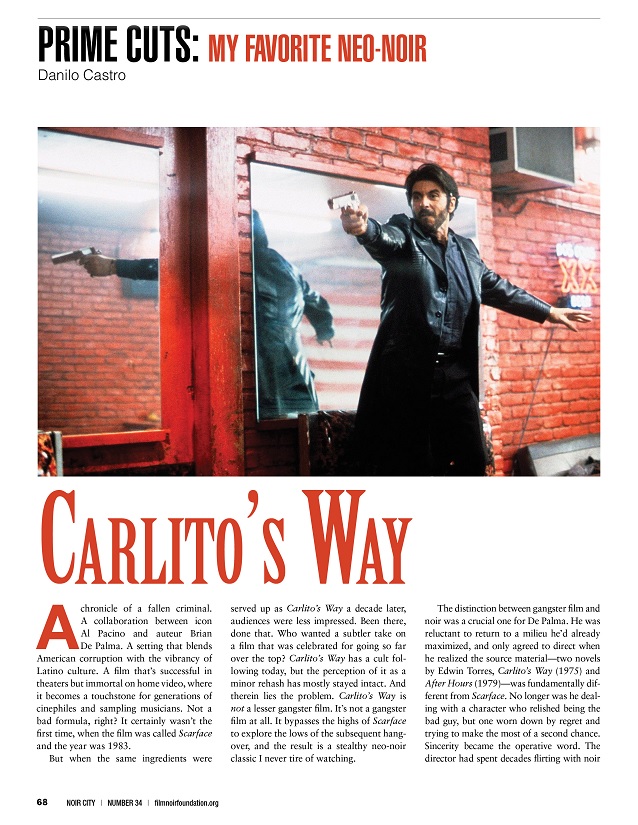

Carlito's Way has a cult following today, but the perception of it as a minor rehash has mostly stayed intact. And therein lies the problem. Carlito's Way is not a lesser gangster film. It's not a gangster film at all. It bypasses the highs of Scarface to explore the lows of the subsequent hangover, and the result is a stealthy neo-noir classic I never tire of watching.

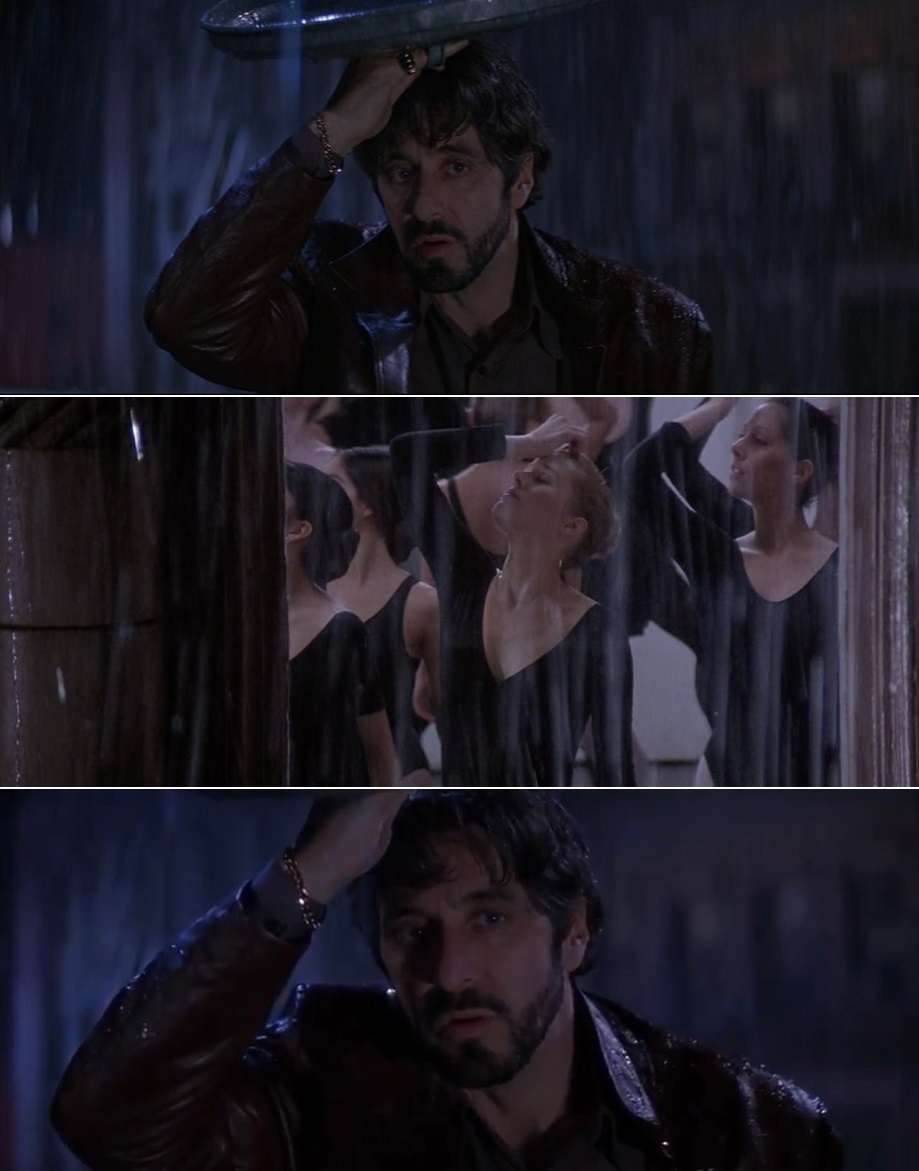

Yes, it’s a mafia story, and a gangster story, and Brian De Palma had seen a film I did called Indochine, directed by Régis Wargnier. He is a very good friend of Régis Wargnier. And after that, he heard the score, he called me up himself to speak to me, and asked me if I would do this. Of course I said, ‘I think I can do this.’ [laughter] I said yes immediately, of course. He’s an iconic director – unbelievable. So this was an incredible assignment. And I suppose I just delved into all my perceptions and years of watching The Godfather and a million other gangster movies, from James Cagney, White Heat, or whatever. You name it. I was brought up in a world where you only had two or three stations. We had ITV and the BBC. And of course, you saw every film that was from the previous fifty years. So I watched so many of these American gangster pictures, and so I felt as if I had a passion and a feel for it. And it was wonderful to have this opportunity to create a jazz-driven score, really. It was quite a jazzy score. And also a great opportunity to write passionate… it was a passionate love story mixed with this mafia background, and a sort of dilemma. It was a guy who had to make a choice between the old world and the new world, finding love and going off with the bride of his dreams. There was romance and there was excitement and there was tension in it, and there was this jazz feeling. And a wonderful drive. And the action sequence at the end, you know, the locomotive. And this movement at the end, it sort of was [handled] out throughout the score… and ultimately planting some subconscious connections to the chase sequence at the end.I’ll tell you an interesting story about the chase sequence. The famous Grand Central sequence that he shot. I happened to be in New York to watch, to see what Pacino, comes in, and he holds the dust bin up over his head, and he’s looking up to his girlfriend Gail who is dancing in a loft in New York. And the following day, I went to see that particular sequence. And I watched the ten-minute sequence. And this was presented to him by the editor. He had never seen it before, cut together, and obviously neither had I. And he turned over to me and he said, ‘Bill’ – it was Bill Pankow, the guy’s name – and he said, ‘Bill, go back to…’ and he went back a couple thousand feet or whatever it was, he said, ‘In this scene, I want DA BA DA BA BA! DA BA BA BA BA!’ In terms of the cut. And that was his only note in that ten-minute sequence. And that taught me immediately that this guy was extremely rhythmical and musical. And it turns out his knowledge of classical music and the repertoire was quite formidable, because we’d talk about Tristan and Isolde, we would talk about anything… At one point, I wrote a piece of music, and he said, ‘Patrick, you’re driving my scene. You’re telegraphing my story.’ And he also taught me, I’m embarrassed to say, to look closer to a picture. Just look at, you think you’ve seen all of it, go the extra twenty percent, study every corner of it. And I thought I was doing that. And so I learned a lot from him. What was interesting was, he said, ‘You go finish the score, I’ll see you in four weeks.’ I said, ‘No, we have to have a meeting.’ ‘No, no, I’ll see you in four weeks.’ I said [laughing now], ‘No, no, no, I’m not ready to score all the other sessions without you having heard nothing.’ Okay. That’s the reason I went to New York – I asked to go over to him and play material to him. ‘Okay, if you like.’ And he loved it and that was it! But I still needed that reassurance before I run the sessions… I think it helps clarify the work and that.

Following up Friday's initial tweet about the 360-degree shot, Nedomansky posted five more video clips from the film, each with its own comment, beginning with a "SPLIT DIOPTER ALERT! 5 examples of Brian De Palma's well-embraced visual storytelling technique in Carlito's Way (1993)." He followed that with a clip of the film's shot near the beginning, which moves from the ceiling fluorescents down to Gail, medics, and police, turning upside down and then moving to show Carlito on the stretcher. "I don't even want to know how they did this shot," Nedomansky wrote. "Just want to appreciate its powerful effect..."

Going back to the scene that had the 360-degree shot above, Nedomansky then tweeted a clip foucusing on Carlito's reactions to the conversation around the table. Nedomansky imagined the brief working conversation between De Palma and Burum:

De Palma: Let give Pacino a nice push-in.

DP Stephen H. Burum: I got this.

Nedomansky concluded the series of clips with a beauty: Carlito holding a trash can lid over his head in the rain as he spies Gail with her ballet class through windows across the way. "Carlito tries to reconnect with Gail after 5 years in jail," Nedomansky tweeted. "A beautiful moment as both characters finish the scene with mirrored body poses via a perfect match cut. Subtle and emotional as fuck."

Coming in at number 24 on the list is Carlito's Way, with a summary provided by Matt Zoller Seitz, although we have to question whether the "World Trade Center subway platform and elevator system" actually appear in the film. De Palma had planned to shoot at the World Trade Center PATH Station, but two days prior to the scheduled filming, it was the target of a terrorist bombing. The climax was filmed at Grand Central Station, instead. Here's the Vulture summary from MZS:

The second collaboration between director Brian De Palma and star Al Pacino, this 1990s blockbuster apes 1970s New York urban potboilers while infusing the story with a melancholy gentleness that’s uncharacteristic of the filmmaker and positioning it as a life-affirming answer to their other team-up, 1983’s Scarface. Pacino plays the title character, a Puerto Rican gangster who gets out of prison and tries to reconnect with his young girlfriend (Penelope Ann Miller) and go straight but inevitably gets drawn back into the criminal life via his coked-up, mob-connected lawyer (Sean Penn). The plot mechanics owe a lot to westerns where an old gunfighter wants to settle down but can’t walk ten feet without some punk dragging him into a duel. The final action sequence, which sees Carlito fleeing Italian Mafia goons on foot through the subway system en route to Grand Central station, is the greatest use of the city’s underground transit system ever captured on film, geographically accurate down to the tiniest details of platforms, transfer points, and local-versus-express routes: MTA-map-nerd heaven. Keep an eye out for a voluptuous cameo by the World Trade Center subway platform and elevator system, which would cease to exist eight years after this film’s release.

Matt Zoller Seitz also provides the summary for #69 on the list, God Told Me To:

A repository of 1970s fears of urban decay, random violence, mass murder, UFOs, goverment conspiracies, and cult machinations, this thriller from schlock maestro Larry Cohen (It’s Alive!, Q) starts with a sniper killing 15 random pedestrians with a rifle from his perch in Times Square and gets weirder from there. Tony Lo Bianco stars as Detective Peter Nicholas, who fails to talk the sniper down (“God told me to,” the man says before leaping to his death). He suspects a connection between that tragedy and the random mass murders that follow (including two more mass shootings and a mass stabbing) and eventually uncovers a mystery that feels like an unholy fusion of Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Rosemary’s Baby, The Fury, and half the conspiracy thrillers released during the ’70s. New York is presented as a mecca for madness, a nexus of every chaotic and sinister impulse obsessing Americans at that time.