JUSTIN CHANG ON MORRICONE & 'MISSION TO MARS'

"IT'S THE MUSIC YOU MIGHT EXPECT TO HEAR AS YOUR LIFE FLASHES BEFORE YOUR EYES"

Posted yesterday afternoon at the

Los Angeles Times,

Justin Chang's "Appreciation: ‘

A Fistful of Dollars’ to ‘

The Untouchables’:

Ennio Morricone made music a movie star" begins rather unexpectedly:

It’s hard for me to recall the most vivid moments in “Mission to Mars,” Brian De Palma’s outer-space drama from 2000, without hearing the great music of Ennio Morricone. That probably isn’t how you expected this to begin, but then, Morricone had a thing for unusual overtures, so bear with me. At one point in “Mission to Mars,” the astronaut characters maneuver their way through the vast emptiness of space — a moment of visual awe to which Morricone supplies a lyrical counterpoint that is at once weirdly playful and hauntingly spare. He helps transfigure the scene from a purely technical endeavor into a kind of weightless dance, a zero-gravity ballet. And when the adventure reaches its climax, Morricone rises to his own peak of spiritual and emotional extravagance — a mighty convergence of strings, celestial voices and insistently brassy melody. It’s the music you might expect to hear as your life flashes before your eyes.

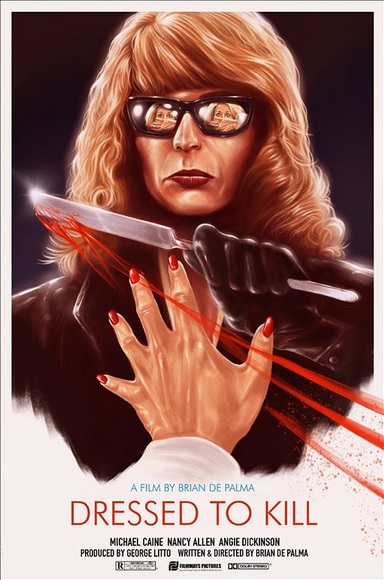

Critically scorned upon release, “Mission to Mars” may not be the picture that springs most readily to mind when we think of this great Italian maestro turned Hollywood legend, who died Monday at the age of 91. If we must think of a “Mission” movie, surely it should be Roland Joffé’s “The Mission” (1986), a historical epic perhaps most fondly remembered today for Morricone’s lush oboe themes, as well as his clever dialectic of classical European and indigenous South American instruments. And if we must invoke one of Morricone’s signature scores for De Palma, one of his favorite collaborators, surely it should be “The Untouchables” (1987), which sets an old-timey underworld mood from the outset — all those low, sinister five-note progressions, timed to a succession of quick, metronomic pulses.

You surely have your own well-worn favorites. But Morricone was a dizzyingly prolific and madly inventive artist, and his career, during which he scored more than 500 films, is much more than a compendium of the obvious and the iconic. Any appreciation at this early stage will but scratch the surface of a mighty edifice that spanned nearly 70 years and ran from giallo horror flicks to classic westerns, and which could apply itself, with equal passion, to the most restless experimentation and the most sentimental bathos. The famously outspoken Morricone certainly had his own singular view of what constituted his best and worst work, and was never afraid to fly in the face of public opinion.

In the article, Chang describes further how Morricone's music is linked to the movies he composed for. "Listen to any Morricone score and 'accompaniment,' a word that critics sometimes default to when writing about film music, starts to feel even less adequate than usual," Chang states. "The effect of his work was not simply to achieve an ideal, harmonious balance of sound and image; he was a far more demonstrative artist than that. More often than not, he seemed all too willing to challenge the image, to draw out the image to languorous extremes, to pummel the image into lyrical submission."

Toward the end of the article, Chang mentions several filmmaking collaborators and the Academy Awards before bringing it back to Mission To Mars:

The Morricone signature is present even in his more restrained, less demonstrative scores for pictures like Gillo Pontecorvo’s “The Battle of Algiers” (1966). In that masterwork of ripped-from-the-headlines realism, Morricone’s terse, electrifying percussion seems to merge with the pounding footfalls of soldiers marching up and down the steps of the casbah. But the effect is entirely different when you watch a film like Marco Bellocchio’s 1965 debut feature, “Fists in the Pocket,” a startling angry-young-man portrait that finds an exquisite contrast in Morricone’s crooning, tinkling lullabies. He wrote much of his music for films directed by fellow Italian artists, among them Bellocchio, Bernardo Bertolucci, Lina Wertmüller, Sergio Corbucci, Dario Argento and Pier Paolo Pasolini, whose transgressive magnum opus, “Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom,” proved a fascinating if far-from-intuitive fit. At the opposite extreme was perhaps the composer’s most frequent collaborator, Giuseppe Tornatore, whose “Cinema Paradiso,” a soft-bellied ode to the magic of movies, might not have been the Oscar-winning art-house favorite it became without Morricone’s gently treacly imprint.

He earned one of his six Academy Award nominations for original score for Tornatore’s “Malèna” (2000), a choice that is viewed most charitably, in retrospect, as a sign of just how revered Morricone had become in Hollywood. It also revealed how eager the motion picture academy was to recognize him after nominating him for his superior work on Terrence Malick’s glorious “Days of Heaven” (1978), “The Mission,” “The Untouchables” and Barry Levinson’s “Bugsy” (1991).

He received an honorary Oscar in 2007, placing him in the company of numerous other venerated artists who were given the academy’s ultimate consolation prize. But Morricone would triumph on his own terms eight years later, finally earning his first and only scoring Oscar, for Quentin Tarantino’s “The Hateful Eight” (2015) — and becoming, at that point, the oldest winner of a competitive award in Academy Awards history.

While that particular score may not rank among his best work, there is something undeniably poignant about Morricone getting his successful final boost from Tarantino, who spent much of his career so lovingly and lavishly quoting the maestro’s greatest hits in movies like “Kill Bill” and “Django Unchained.” Tarantino knew that Morricone’s music was something primal and even physical in its presence, something that seemed to bubble out of the landscape itself. And those landscapes could be as different as a dust-choked Leone desert or the deadly Antarctic tundra of John Carpenter’s “The Thing” (1982) — or, yes, the vast expanse of De Palma’s outer space, one of many cinematic cosmos that Morricone colonized with his own limitless sense of possibility.

Back in March,

Back in March,